Inside the homes of Daniel Johns and Kasey Chambers: a rare look at music icons

The Australian’s music writer reveals the benefits – and the occasional costs – of interviewing some of the nation’s best musicians and songwriters at their homes.

The American magician duo Penn & Teller had a favourite onstage trick that broke with convention by placing the onus of responsibility on their audience: whether or not they wished to learn the truth was left up to the individual.

In their act, Penn Jillette described how his mute offsider, Teller, was about to escape from inside a double-locked box – an apparently impossible task.

He then gave onlookers a choice: they could keep their eyes open if they wanted to learn the secret of how Teller’s escape was done. Or they could keep their peepers shut tightly if they wished to maintain the illusion that magic really, truly exists.

In this offered choice between head and heart, I would always choose the latter.

As a journalist, I’m professionally nosy: I love learning new information and sharing it with others. That’s the job, and in some ways, I was built for it.

But I also hold a parallel and contradictory opinion: I believe some secrets are worth keeping, particularly in magic, where the best tricks conjure an awe that resists analysis.

Sometimes, choosing to be mystified is the kindest, boldest choice.

Sometimes, ignorance is bliss.

The Honour System, Penn & Teller called this trick, which took them more than 20 years to perfect. I love the elegant simplicity of its execution, and the surprising generosity of their offer – eyes closed, or eyes open? – and it came to mind while writing this essay, because the subject is me.

As a boy, I pored over magazines like Rolling Stone, Spin, Kerrang! and Juice, drinking in the conversations and interactions with great musicians that the best music writers from Australia, America and Britain captured in text. Most entertainment journalism is transactional – an artist has a new project to sell, and the writer gains access because of that need to promote the work – but the best articles were always those that uncovered deeper insights, often based on investing significant time together.

When reporting feature stories, I’m always much more interested in meeting artists on their home turf than in an artificial “third place” located somewhere between where they work and where they lay their head to sleep.

I may have subconsciously adopted something journalist and novelist Trent Dalton told me long ago when I interviewed him about a pair of magazine stories he’d written, which were centred on the lives of an average teenage boy and girl living in Brisbane.

Dalton was then on staff at The Courier-Mail’s Qweekend magazine, before he joined The Australian and then went on to write mega-selling novels.

He spoke about “the beauty of arriving somewhere at 6am” as a reporter. “Can you imagine a kitchen in those early hours?” he asked me in 2011, when I was a lowly, uncertain freelancer. “A mum in a kitchen; it’s just a really safe space. It’s a beautiful spot to have a chat to any mum.”

That anecdote relates to the experience of Dalton – then aged 32 – arriving at that comfortable locale in order to ask the mother of a 15-year-old boy deep, emotive questions about what it feels like to give life to someone, and to parent them as they grow and mature.

Writing, recording and publishing songs isn’t nearly as dramatically life-altering as childbirth, but artists tend to be sensitive, thoughtful, emotional people.

Like parents, they care deeply about what they’ve created and sent out into the world, but there’s an artistic twist: any sense of pride attached to the act of creation is often mirrored by an insecurity that is forever tapping on the door to their brain, whispering: but is it any good?

Meeting and interviewing artists in a “third place” – cafe, restaurant, bar, park, hotel lobby, backstage at a music venue – is fine, and often a necessity if they’re on tour and haven’t stepped over the threshold in weeks or months.

That’s why I met the members of US rock act Eagles at a boardroom inside the Los Angeles office of the band’s management company for an interview between stadium shows, ahead of a 2019 Australian tour.

When an assistant went around the table, taking down coffee and tea orders, guitarist and reformed wild man Joe Walsh – now famously sober – was last in line, and made a quip with perfect comic timing: “See if they have any amyl nitrate.”

That’s why I met Nick Cave at a Sydney hotel mid-tour last year, where the chronic insomniac described that he’d recently found himself awake in the small hours and decided to drive aimlessly around the inner city. I liked that image, of one of Australia’s great rock frontmen prowling the streets behind the wheel. “I’m not, like, looking for action,” he replied, frowning. “I just don’t want to lie around my f..kin’ hotel room.”

That’s why I spent time talking with each of the five members of Cold Chisel at a Sydney rehearsal space last year, as one of Australia’s favourite bands geared up for its first tour in nearly five years. Drummer Charley Drayton surprised everyone – even himself, perhaps – by tearing up at my first question.

“It’s emotional,” he replied, “Because we’ve been through a lot to get back here, and I love playing music with these guys.”

But in many cases, their home is the place they want to be – and where time, resources and their permissiveness allows it, I’ll always push to meet them there.

An artist in a kitchen; it’s just a really safe space. It’s a beautiful spot to have a chat to any artist.

One day last year, I ended up in the kitchens of two of Australia’s greatest artists within the space of a few hours. On a Tuesday in late August, I travelled from Brisbane to knock on Sarah Blasko’s front door in Sydney’s inner-west for a chat about her seventh album, I Just Need to Conquer This Mountain, for what would become a Review cover story.

She poured me a coffee into a Paul McCartney mug, and we got to work: me leading the conversation with my curiosity about where the new songs came from, while staying wide open to any discursive alleyways that presented themselves. Blasko had tidied the toys of her two young sons, and when I asked if she had something booked directly after my visit, she had a funny line: “Lunch and a load of washing,” she replied, smiling.

“I’ve always got stuff to do, but I’m not in a rush or anything. I mean, that’s why I’m doing (the interview) here at my house. It seems like I’m being welcoming, but I’m actually just being lazy. ‘Where can I do it, where I have to put in the least amount of effort…?’,” said Blasko, laughing.

“I’m so honoured that you’re willing to trust me enough to let me into your house,” I said.

“Well, we’ll see,” she replied. During a bathroom break, I noticed something that drove home the transient life of touring artists, particularly those with young families at home: a KISS-themed calendar noting handwritten dates marked “Mum away”, “Mum gig” and “Mum back!”

After a lovely chat at her kitchen table, Blasko casually stepped into the next room to perform a couple of songs at her piano for my camera lens. Her exquisite vocal tone filled the room while I sat, watched and listened – an audience of one, spellbound.

That afternoon, I drove 103km north to the NSW Central Coast town of Bensville, population 2500, to meet country musician Kasey Chambers, who lives on a bucolic spread where her home studio, dubbed Rabbit Hole, is a short walk from the house.

Since it was a Tuesday, Chambers was childminding: not one of her own brood, but the one-year-old son of her ex-husband and fellow musician, Shane Nicholson, who lives nearby with his partner. The boy’s name was Jude, and very soon after my arrival, he requested a move from her arms into mine.

In the “yes, and…” improvisatory spirit that feature writing demands, it seemed somewhere between rude and insane to deny the boy’s open-hearted request – which is how I ended up carrying him for an extended period as I got a walking tour around her beautiful, bush-abutting property. “Have you got a new friend?” she cooed at him. “Or were you just sick of me, and there’s a new face?”

Chambers loves cooking, and she loves talking, so we spent a lot of time in her kitchen that afternoon as I reported what would become a cover story for The Weekend Australian Magazine.

While Jude played with his toys on the hardwood floor, we went deep on her earthy, mongrel, self-helpish memoir Just Don’t Be a Dickhead and its sister album, Backbone, which she was telling me were designed to be consumed as companion titles via their intertwined chemistry.

“As one of the few people to have heard the album and read the book so far, I completely agree,” I said, while sitting at her kitchen bench as she prepared food for the mob of musos working in the nearby studio.

“I think you’re the only one – or you’re the only one I’ve talked to, anyway,” said Chambers.

“Just to clarify: are you saying that we have good energy?” I asked.

“We do, don’t we?” she replied, momentarily shaken, before clocking my grin. “I mean, obviously. I’d met you before – but I wouldn’t want every journalist to come to my house.”

“Well, thanks for your faith and belief in me,” I said.

“’Yeah, he’s all right’,” she said, as if describing me to a friend. “’He’s not a dickhead; he wasn’t that day we met, anyway…’”

“Evidence of dickheadery: zero, so far.”

“We’ve still got tomorrow to go,” said Chambers, smiling. “In saying that, I think it’ll probably be more the other way around, where you’ll see me in my natural habitat, going, ‘Oh yeah, she’s still a dickhead a lot of the time…’”

Not true: she’s a gem. During our hours of chatter, friends and family members came and went from the house, including her mum, Diane. During a break, I snuck a look at her vinyl collection – like I said, professionally nosy – and found Eminem, Cold Chisel and Paul Kelly sleeves rubbing up against the likes of Billie Eilish, Bruce Springsteen and Bliss N Eso, as well as a few of Chambers’ own records, proudly mixed in among her fellow stars.

Home visits for stories are a substitute for being in the room when an artist is doing the real work of creativity. In my experience, opportunities to capture these musical moments are vanishingly rare, for a good reason: sitting in on writing or recording sessions, even as a silent observer, changes the dynamic, and not always for the better.

In physics, this is called the observer effect, wherein the act of observation disturbs what’s being measured. So it is with artists, who are finely attuned to unusual faces and bodies appearing in rooms where they’re attempting to conjure something new and vital. Songs can be flighty creatures to summon, and like shadows glimpsed in your peripheral vision, they can disappear as soon as you turn your head. Best not to add other eyes to that delicate process.

Watching artists create is a rarity; sleeping under the same roof is even more so, and until recently, that was a bright line I’d never crossed. Until, within the space of a few months, I did it twice with well-known artists while reporting cover stories for Review.

When writing about Tim Freedman of The Whitlams in March last year, the location was half the point of the story.

The singer, songwriter and pianist was releasing country-coloured music under the new moniker of The Whitlams Black Stump, blending songs new and old, but what piqued my interest was learning that he had invested in an unusual property near Byron Bay in 2009.

“Artist releases new album” is rarely an interesting and newsworthy story in itself, but “artist releases new album while running a Balinese-style resort and wedding venue”? I’m in – especially once I learned Freedman was up for talking about his past life as a serious gambler who took pleasure from the cat-and-mouse game of one-upping major gaming companies before they cottoned on to what they were losing from unusually sharp betters like the bloke who co-wrote Blow Up the Pokies.

On greeting me at the front door of his place, named Barefoot at Broken Head, Freedman had been eyeing off all the parts of the sprawling five-bedroom home that were showing signs of wear and tear.

“I haven’t been here for a while, so it’s always frightening when you walk in and cast your owner’s eye over it, and the thousands of dollars just ring up in the back of your mind,” he said, grimacing. “Oh, I’ve gotta fix that curtain rod, and that sliding door’s getting very heavy…’ – it’s the reality of complicating your life with property.”

I filmed Tim performing a couple of songs at his piano, then we hopped on bikes and cycled out to the nearby beach together for some afternoon exercise. Following dinner in central Byron – wherein the Whitlams leader eyeballed some attention-seeking locals and memorably quipped, “The clueless self-approval involved here has to be drug-induced” – we returned to his place, bid each other goodnight, and retreated to opposing ends of the property.

Four months later, while visiting the central Queensland city of Rockhampton for a story on Christine Anu, the artist learned I was seeking advice on nearby hotels and torpedoed that idea in lieu of a surprising offer to stay in her guest room.

This novelty presented a quandary: while reporting, distance from subjects can be helpful. Anu’s kind offer chimed beautifully with her open, warm personality, though, and any concerns I’d felt went out the window as she and her partner, Scott, took me on a road trip out to Yeppoon for lunch and back, chatting all the while about her career, which was soon to be burnished by the release of a highly personal album titled Waku – Minaral A Minalay.

I tagged along as the pair shopped for supplies at a supermarket, and from across the fruit and veg section I watched as a great Australian performer decided on the items needed to cook a dish of curried chicken wings and coconut rice. Back at her home, I sat at her kitchen bench, sipping beer and listening intently to her stories. She got so carried away with the telling that she left the fridge door open for minutes on end.

“You’ll come to find I am that person – and I just imagine, my aunties and uncles would have gone: ‘You made him go and stay in a hotel? Ohhhhh!’” she said with a laugh, mimicking cries of shame and outrage. “I mean, I probably would if there was something I didn’t want him to see or hear.”

By now the memories are coming thick and fast, and it’s the small, strange details that stick out. I recall that indie pop artist Gotye had an inversion board for muscle-balance therapy inside his home at the Mornington Peninsula; I know because he let me try it in 2013. As I was strapped in and slowly inverted into a fully upside-down position, feet facing skyward, I trusted that the Grammy Award-winning artist otherwise known as Wally de Backer wasn’t going to drop me on my head.

At the time I was reporting a book about musicians and drug use titled Talking Smack, wherein the likes of Steve Kilbey, Lindy Morrison, Holly Throsby and rapper Urthboy all kindly let me through their front doors to talk frankly about a tough subject.

In another interview for that book, Grinspoon singer Phil Jamieson invited me to meet his young family at their Port Macquarie home; earlier, I’d been entrusted with taking his dog Pablo (RIP) for a walk around the surrounding streets, and Phil’s children had proudly given me a tour of their bedroom. His eldest child played a song for me on her recorder, then showed me a journal entry that described her dream at that point in time: to become a musician, just like her dad.

In 2018, my first year of working on The Australian, Andrew Farriss of INXS jumped in his ute and drove me to the highest point of his farm for a sunset snack of corn chips and Coronas, as one of the nation’s greatest pop songwriters regaled me and photographer Glenn Hunt with the strange and compelling story of how, in 1992, he decided to buy a 1500ha property near the northeast NSW town of Barraba, which he now shares with his wife, Marlina.

The following year, after a pub lunch with Hilltop Hoods in Adelaide, we stopped in at a bottle shop then repaired to the home of MC Suffa, aka Matt Lambert. Inside his lushly appointed studio in the Adelaide Hills, the hip-hop trio appeared to be intent on continuing to celebrate the recent completion of mastering the tracks for their eighth album, The Great Expanse.

Suffa split a six-pack with fellow MC Pressure, and my invitation didn’t extend to that afterparty, although Suffa’s young daughter seemed pretty keen on breaking up the Hoods’ soiree by insisting on hearing a high-volume playback of her favourite song, Baby Shark, much to our amusement.

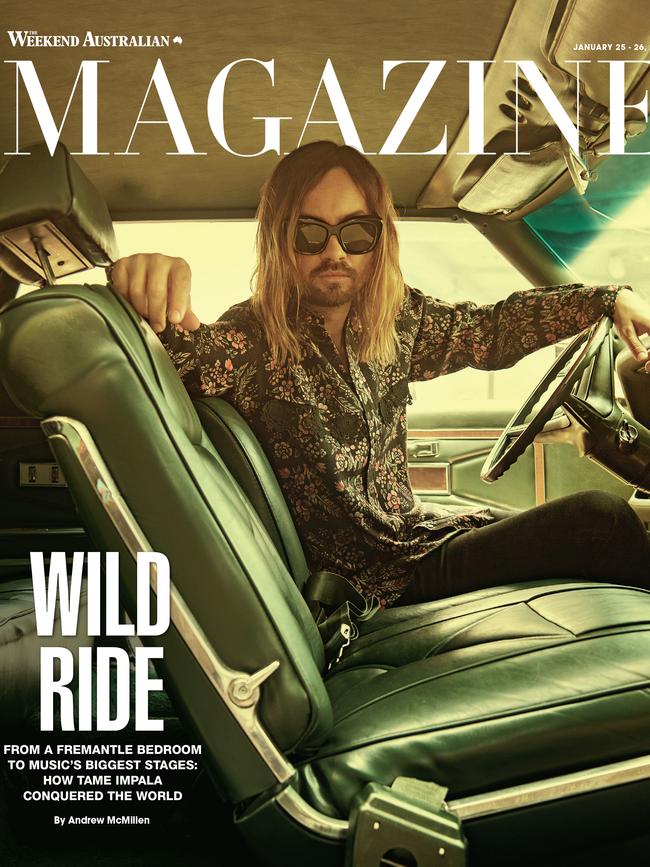

Alcohol is a recurring character in some of these stories, for good and for ill. In late 2019, a couple of hours into visiting Tame Impala (aka Kevin Parker) at his Fremantle studio – which was once his home, until he knocked out all the internal walls and bought another place down the road to improve his work/life balance – we started drinking.

As we spoke in detail about his obsession with finding the perfect drum and bass sound, while I reported a magazine story ahead of the release of his fourth album The Slow Rush, the pale ales were going down easy; so easy, in fact, that after two beers each, Parker looked at my audio recorder and had the wisdom to put a pause on his consumption until the interview was over. We later walked to a nearby bar to meet his bandmates and wife Sophie; with Kevin’s blessing, I managed to convince her to speak on the record about her husband’s globally loved music, and the toll that its long gestation process takes on him.

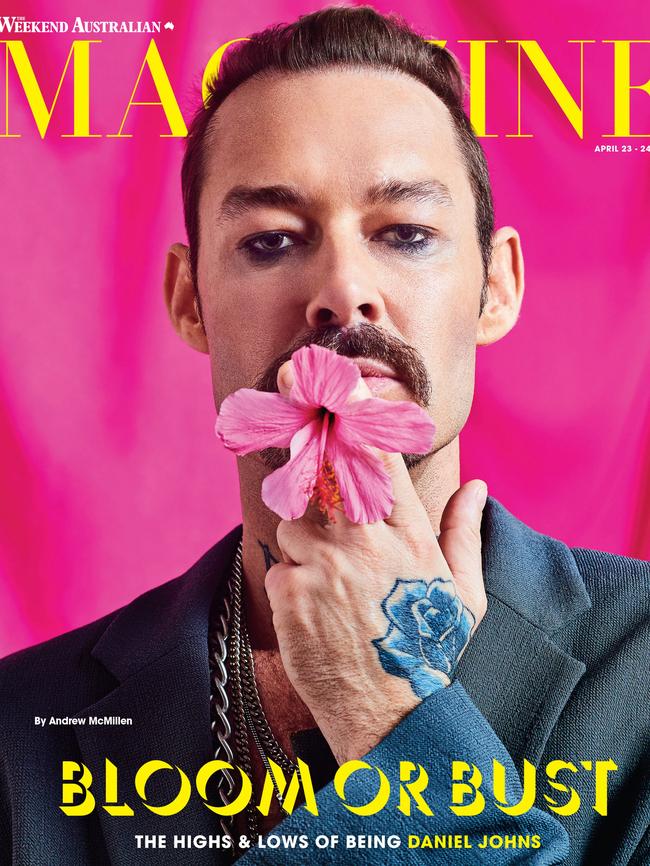

That’s an example of the good that adding booze can do to feature writing, I suppose, as tongues loosen and subjects relax. I thought I had encountered another instance of this in 2022 when I visited Daniel Johns at his home near Newcastle for a magazine story. This was the only place that the former Silverchair frontman wanted to meet – going out was not really his thing, to put it mildly – and so the only formality to gaining access was in establishing my bona fides.

Once he buzzed me in through the front gate, Johns greeted me with a hug, and my afternoon spent there was remarkable, not least because I’d been captivated by this man’s art since I was a small boy. We bonded over a shared love of music and traded favourite Elliott Smith tracks, and at one point he leapt up from his couch to bang out a John Lennon song at his piano – a private performance for me, by one of the country’s most famous recording artists who famously no longer performs in public.

Comfortable at home, he was in a playful mood: when I took a bathroom break, Johns picked up my recorder and said into the microphone, “So, I’ve got a body buried downstairs, honest. This is my confession in case anyone ever finds me, this is… oh, shit he’s back!” he said, as I returned to the lounge room.

Hung on his wall near an assortment of musical instruments was a curious image of a shopping trolley filled with people and objects headed for a cliff, which Johns said reminded him of the end of his famous band.

“That’s a print I got when we were doing the ill-fated Silverchair sixth record,” he told me. “The guy that was engineering the record with me had a friend who was a painter, and he had all these prints on little postcards. I asked him if I could get a print of that, because I felt like that’s exactly what was happening to the band. It was like we were just falling off a cliff; we’re not going to be able to solve this. The captain’s at the hill – that’s the record company – and all these minions are just dying. It’s a very uplifting piece of work!”

“I can see why it spoke to you,” I offered, and we both cracked up laughing.

It was in his kitchen that the afternoon took a boozy turn, and I’m still not sure if it was for the better or worse.

Better for my story, certainly. On his rooftop, with the wide sweep of Merewether Beach before us, we continued talking, and drinking, and sharing our admiration for the songwriting of The Vines’ Craig Nicholls and the greatness of Warren Ellis, the Ballarat-born Dirty Three violinist and Nick Cave’s co-composing right hand man.

(An aside: Ellis quit drinking in 1999. “Without that, I wouldn’t have had the life that I’ve had,” he told me in 2019 of his sobriety. “It’s really the only way forward for me, and it’s served its purpose: a lot of what I’ve done just wouldn’t have been possible, because, a) I doubt I would have been around and, b) I wouldn’t have been able to do it. I owe everything to that.”)

At the time of our meeting in March 2022, Johns was not sober, and we continued amiably bending our arms as the sun set over the Pacific Ocean stretching to the horizon. Midway through a story I was telling, he stood up, walked to the edge of the roof and opted to relieve himself into the void,while his girlfriend and I cackled at his bravado.

“I don’t think you know how much I don’t give a f..k,” he told us, when we joked that a nearby hang-glider would sell pictures of his penis to the Daily Mail. When he realised my recorder was still running, he confirmed, with a cheeky grin: “So you just recorded me pissing off the balcony, into my pool...?”

Downstairs he played me his new solo album FutureNever at high volume, then started scrolling his phone and blasting unreleased tracks, some of which blew my mind. It was late when his girlfriend eventually ordered me an Uber back to my hotel; it was a good call, as Daniel was wasted, and I wasn’t far off.

Nine days later, Johns crashed his car while drink-driving near Newcastle. His blood alcohol reading was 0.157, more than three times the legal limit, and he immediately self-admitted to a rehabilitation centre – an unfortunate series of events that cast my Tuesday evening with Daniel in a new light.

What was clearly a golden opportunity for me as a journalist had some of its gloss knocked off by the realisation that I may have egged him on, to his detriment. He’s capable of making his own decisions, but that’s still a shitty feeling as a house guest; in truth, the thought has haunted me.

In swallowing a cocktail of guilt and dread, with a fear chaser, for years I’d avoided checking the audio recording to ascertain whether it was he or I who first suggested adding booze to the equation. When it came to that particular Honour System, I opted to keep my eyes squeezed tightly shut. But writing this essay forced me to check the proverbial tape:

“Would you like an alcoholic drink?” Johns asked, as we stood at the fridge.

“Yeah,” I replied.

“What kind? Do you want that?” he asked, pointing at bourbon and cola cans. “Or vodka? Or we could have champagne…?”

“I could do champagne, if you’re offering,” I said.

Cue mild relief, three years later, in not being the cork-popping instigator, for what little that’s worth. I hope Daniel’s doing well, and I hope that his unreleased music is some day heard beyond his home stereo.

Two months ago, it was zero-alcohol beer on the menu when I travelled to Byron Bay to meet Midnight Oil drummer and songwriter Rob Hirst at the coastal home he’d owned since 1997, and used as a regular escape from the noisy bustle of Sydney and the demands of his band’s long touring life.

All I knew while driving south in mid-March was that Hirst’s health had gone south of late, but I didn’t know the specifics of his illness until he told me in person: diagnosed with pancreatic cancer two years ago, he had undergone chemotherapy, major surgery and radiation to treat the disease, but it hadn’t worked. At 69, he was now measuring his remaining life in “weeks and months”, not the years he’d hoped to continue notching after the Oils finally finished touring in 2022, after 46 years of globetrotting action, on and off.

Hirst was viewing his impending end with clear-eyed stoicism and gratitude for what he’d managed to achieve during his time upright – or sat at a drum stool – while bashing his way into Australian music history with gusto.

He hadn’t lapsed into fatalism, either, and was determined to press on as long as the cancer allowed him – hence the Heaps Normal beer in place of the real thing, with which Hirst and I toasted alongside his wife, Lesley Holland, towards the end of six hours of freewheeling conversation at their kitchen table.

As a journalist, there is no greater gift than to be entrusted with telling the life story of a public figure who knows his time is nearly up. I was deeply honoured, but while staying overnight at a hotel in central Byron Bay and digesting what I’d learned that day, one of many questions circling my mind was this: why had Rob elected to talk to me about what he’d been through?

When I returned the following morning and asked him, he replied, smiling, “Because I think we’ve had really good chats in the past, and I knew that you would be really well-researched; not as well-researched as you actually are. I think you know more about us (Midnight Oil) than we know about us.”

“And also because, if you’re going to do this kind of thing, it needs to go out big-time, rather than just kind of seep out through (smaller outlets),” he continued. “This is a big thing for me, and (The Australian’s) coverage is big. And you are a music journalist; you know the history of the band. You’ve seen the band countless times, so I don’t have to fill any of that in. You know a lot about ‘the journey, man’ – so far. We covered a lot more ground than I imagined we would, but I don’t begrudge that for a minute. I’m glad, because I’m not going to do any more of these.”

With each of these stories, and hundreds more besides, the goal was always to uncover and share intimate insights about musicians in a manner that hopefully entertained, educated and inspired the reader. The best of them may have done all three, like the strongest articles in those glossy pages of Rolling Stone et al that I hungrily read as a teenage daydreamer.

In all but the Hirst example, there was a product to sell, but if I did my job well, the transactional nature of music journalism was buried beneath a well-crafted story based on rare access into private spaces. I’m in the business of taking serious artists seriously, and every interaction I have with musicians and songwriters in this role is a privilege.

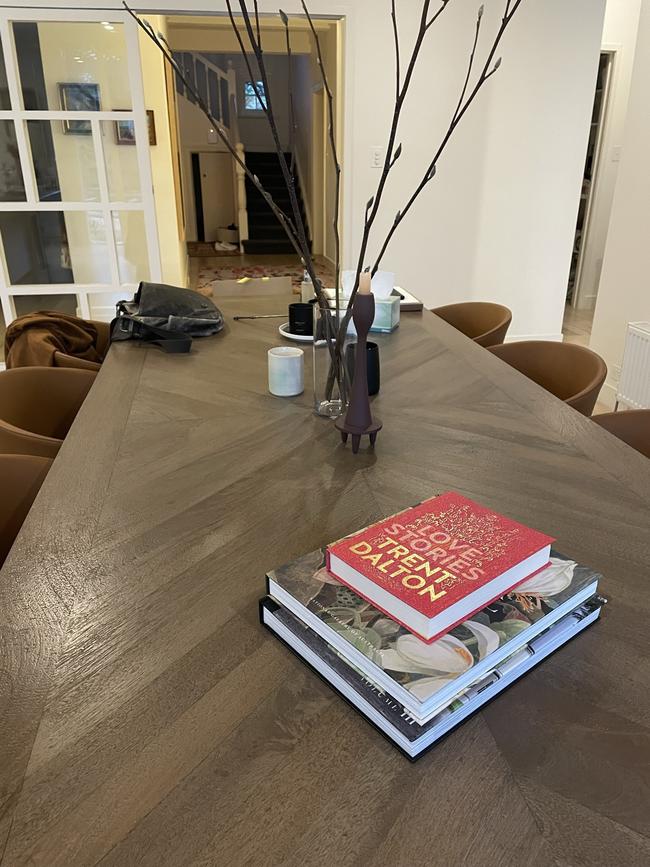

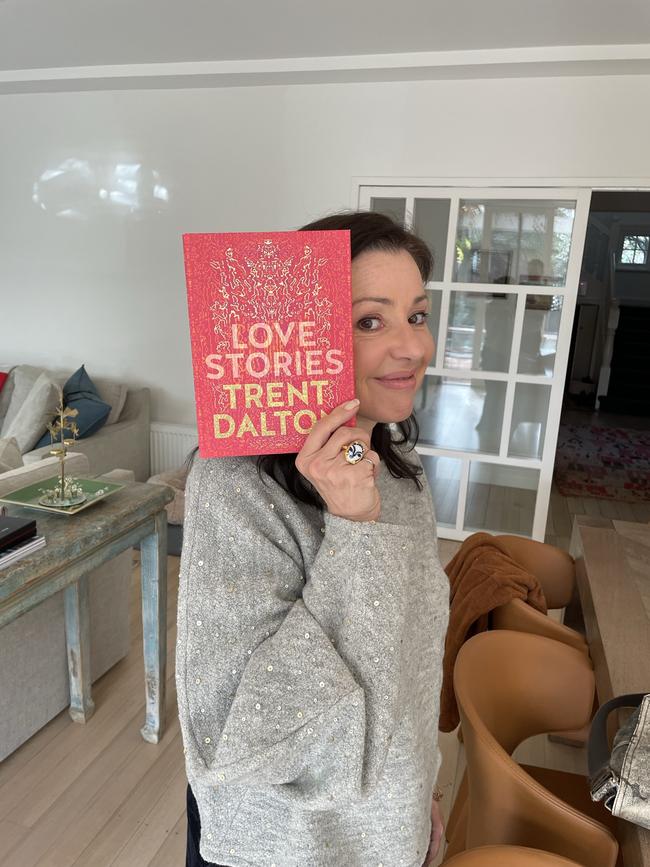

While visiting singer Tina Arena’s Melbourne home in 2023 for a profile ahead of her 13th album, titled Love Saves, I found a copy of Trent Dalton’s book Love Stories. Not in her kitchen. Instead, the book took pride of place atop her long wooden dining table, in the room right beside that beautiful spot to have a chat to any artist.

Later that afternoon, I sat quietly in Tina’s front room as one of Australia’s greatest singers opened up her voice and practised alongside a pianist with my phone camera lens trained on her.

While she sang, concentrating on the colour and timbre of her instrument, Tina’s eyes were closed. Mine were wide open, and leaking.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout