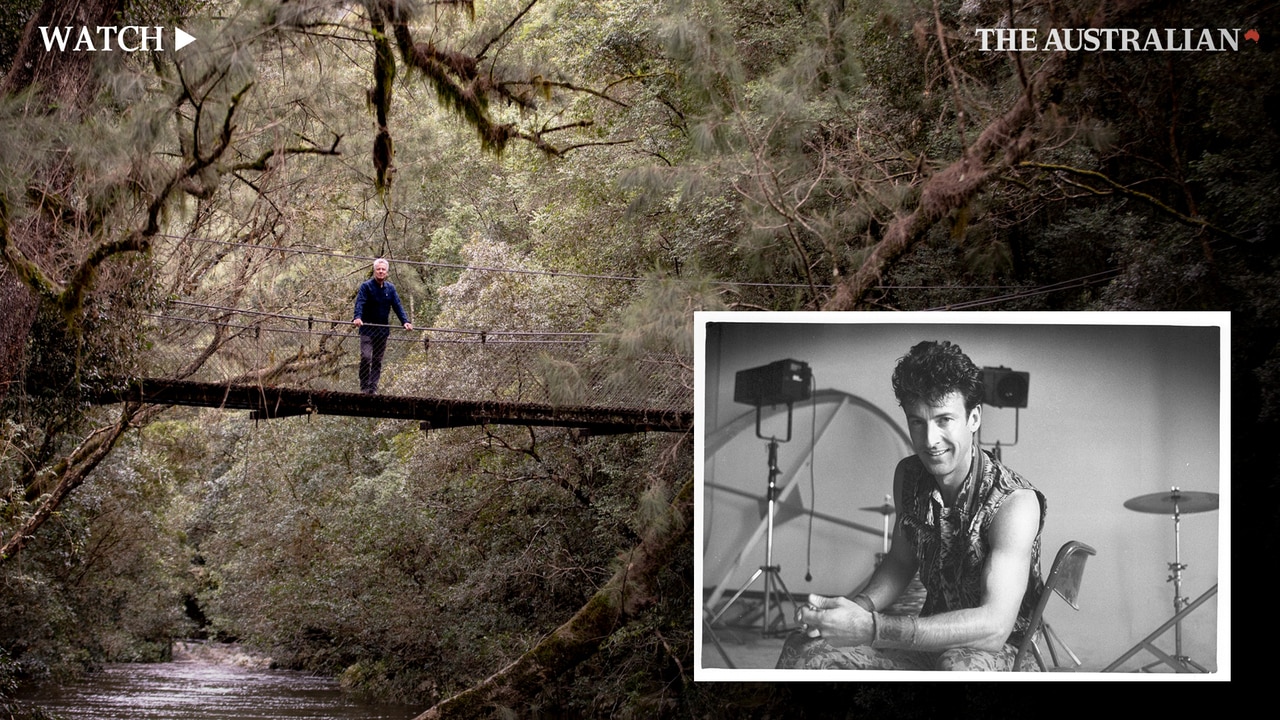

Midnight Oil drummer Rob Hirst reveals pancreatic cancer battle

Just six months after completing Midnight Oil’s epic farewell tour, drummer Rob Hirst was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He has been fighting it in secret ever since. Until now.

This is a story of life, death and what happens in between, driven by one man’s unending belief in the colossal power of music to stir our blood, bones and brains.

It’s the story of a boy who became one of the world’s greatest rock ‘n’ roll drummers, set to the metronomic beat of a clock ticking down to zero.

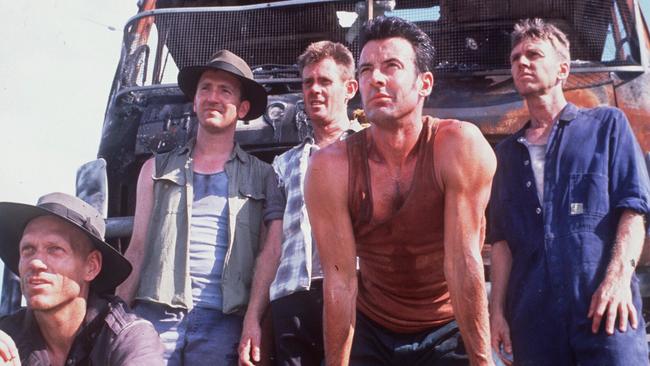

For most of his 69 years, Rob Hirst played drums in Midnight Oil, a group he formed in 1976 and which issued 13 albums before downing tools in late 2022. The quintet concluded its 46-year run with 47 gruelling concerts in nine countries that cemented the Oils’ revered status with stirring vitality. Its final hometown gig was a four-hour, 40-song epic. Job done.

Hirst is a husband, father, grandfather, son, brother, author, songwriter and musician outside of Midnight Oil, but his role in the band – as its drummer, backing vocalist and songwriter – will fill the first lines of his obituary.

As he approaches his 70th birthday on September 3, though, Hirst doesn’t know if he’ll be there to blow out the candles, or even if he’ll live to see the birth of his next grandchild, due in July.

He’s been living with pancreatic cancer for two years – an inordinately long time for a disease known for swiftly felling those who get it. He’s had a remarkable run so far, but that ticking clock is growing louder. The time to talk is now.

When I meet Hirst at his home in Byron Bay in mid-March, he’s riding an updraft, on a break from treatment, having recently been discharged from a Sydney hospital following a bout with sepsis.

As for his prognosis, which has eclipsed initial expectations after they caught his cancer “early” at stage three, he talks in terms of weeks or months. His oncologist describes him as a “star pupil” and says the cancer is “pretty stable at the moment”, with tests conducted every six to eight weeks.

“So it’s ongoing,” says Hirst. “I’ve had pretty much every treatment known to man – every scan, ultrasound, MRI. I’ve kind of had ‘the works’ – but today I’m feeling really good,” he says, smiling. He’s wearing the beachside attire of shorts, sandals and sunglasses, with his silver hair tucked under a trucker cap.

Early on in Midnight Oil’s performance career, Hirst’s style of attacking the skins and cymbals was so ferocious that members of the road crew took to nailing his drum kit to the floor. It was a propulsive force, onstage and off: Hirst drove the band like a B-double truck barrelling down life’s highway for nearly half a century.

So what happens when that prime mover breaks down? It’s not unusual for famous people to keep a terminal illness private until they die. But Hirst has chosen to talk openly now, for reasons that we’ll come to.

He says he only wants to tell this story once, and he wants me to tell it true. So does Lesley Holland, Hirst’s wife, who shared him with Midnight Oil throughout their marriage, and now has to share him with cancer.

“I guess that’s the thing with this disease,” she tells me with a shrug. “It looked like we were going to finally get to be free – and this little f..ker’s come and spoiled it.”

If you’d asked him on that final Oils tour what he knew about the pancreas, Hirst’s answer would have been not much. But after encountering some peculiar stomach grumbles that led to blood tests and scans, mere months later in April 2023, a stage-three tumour on his pancreas was discovered close – too close – to a major blood vessel.

His doctors blitzed it with chemotherapy, then major surgery and radiation. But cancer is a persistent prick of a thing, and if it’s pancreatic it usually wins. The survival rate for Australian men five years after diagnosis is about 12 per cent.

Now Hirst knows a lot about the pancreas.

Locals in Byron Bay are known for worshipping barefoot at the altar of alternative medicine, but Hirst is no new-age believer, and has become fluent in the medical science. He talks in precise language, with a clear-eyed appraisal of what lies ahead, only occasionally clouded by fog: half an hour into our conversation he says with a chuckle, “Sorry – thank you for bringing me back to the point; I’ve got ‘chemo brain’, which is my excuse for everything now.”

The diagnosis was, he says in his gentlemanly way, “quite a shock, to say the least. Here’s a band that used to rush off stage after a three-and-a-half-hour show and have a chamomile tea.” The Oils were, he laughs, “famously the least [drug] abusive band. So that began ‘a journey’, as they say up here, of almost two years”.

Every time he goes into hospital he loses weight, but he puts it back on with good eating and a predilection for Mini Magnums. “And I use savage gardening to get my strength back,” he says, gesturing at his freshly tamed backyard, which copped a beating the week before from Tropical Cyclone Alfred. The 1940s-built beach house was undamaged.

Life for Robert George Hirst began in Sydney in 1955 on a five-acre, funnel-web-infested bush block outside Campbelltown, 55km from the CBD, before his parents Peter and Robin moved seven-year-old Robert and his two brothers closer to the harbour.

Hirst filled his growing brain with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks and the Dave Clark Five. He was given his first drum kit after a brush with serious illness: persistent leg pain at age 12 led to an operation on his right femur, which uncovered a benign tumour called an eosinophilic granuloma.

He had to relearn how to walk on the children’s ward at Sydney’s Royal North Shore Hospital. And on the day he was discharged, his father, a jazz buff and World War II veteran, took him into the city and bought him a Star drum kit with a nauseous volcanic finish. Young Robert attacked those drums with extreme gusto, before his femur had properly healed, with his leg set at a strange angle facing out toward the bass drum pedal, where it has remained ever since.

A few years later, while still in high school at the prestigious Sydney Grammar, Hirst hauled his drum kit into the attic at Jim Moginie’s parents’ place on Sydney’s upper north shore. With bassist Andrew “Bear” James, this trio was named Schwampy Moose, then later Farm (an acronym for F..king All Right Mate). From 1976 it was a five-piece named Midnight Oil.

Nobody expects the timekeeper in a rock ‘n’ roll band to pen memorable lyrics and melodies as well, but from the Oils’ earliest days that was Hirst’s job. It was also booking the gigs as Midnight Oil’s star rose and the band played some 180 gigs a year on the east coast pub circuit – along with figuring out where to sleep, whether on beaches, under their cars or inside the halls they played. “Rob was brash, funny and super intelligent, contrary to the clichéd view of drummers,” wrote Moginie in his 2024 memoir The Silver River. “He was organised, articulate and highly driven… Rob was the band’s engine room, onstage and off.”

And it was Hirst, then an arts-law student at Sydney University, who placed a newspaper ad seeking a singer for Farm, and who answered the phone when a long-haired surfer named Peter Garrett, also a law student, called in 1975.

In his 2015 memoir Big Blue Sky, Garrett recalled his audition: “The songs thundered, a waterfall after heavy rain, as the boys’ fingers flew up and down their respective fretboards. Rob, grinning under a shock of black spiky hair, smashed at his drums in a flurry of staccato movements as the sound cannoned off the walls of the genteel school’s hall.”

The decision to enlist an unforgettably long-limbed, loudmouthed vocalist may have overshadowed Hirst somewhat; people assume the frontman wrote all the songs. But it has never bothered the drummer, who praises the lack of ego in the band. “We had amazing chemistry, and we remain better friends than ever,” he says.

Anyway, with an onstage preference for singlets and cut-off shirts that showed off his sculpted arms – and a nose that the band’s crew once described as “like a Concorde sticking out of its hangar” – Hirst was only a fraction less eye-catching than the tall, bald man out front.

The late journalist Andrew McMillan wrote in his 1988 book Strict Rules, which documented Midnight Oil’s landmark tour of remote Aboriginal communities with Warumpi Band in 1986: “It’s fair to say that he’s more relaxed than his colleagues, a man who can be relied on for a smile, a firm handshake and a warm word … of all the Oils, it’s Rob who consciously cherishes and nurtures the band, its fans and its position.”

It was on that tour that the drummer’s iconic corrugated tin water tank entered the picture: the band’s road crew found it discarded beside a red-dirt road and chucked it in the truck, thinking it might be useful to a man who enjoyed making a racket. It stood over his right shoulder at every concert for decades, awaiting the drum solo during Power and the Passion.

McMillan also recorded how Hirst’s moods could darken: “Those rare times,” he wrote, “when depression sets in, for reasons unfathomable to anyone outside the tight inner circle.” McMillan noted how Nick Launay, who produced the Oils’ album 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 in London, said Hirst’s “gloominess is like an English summer”.

Hirst has said that while recording the album with Launay in 1982 he was suffering panic attacks, fuelled by the responsibility he felt for the group he’d willed into existence as it shed the skin of its pub-rock days and embraced a more experimental sound.

While touring north America shortly after the 9/11 attacks, Hirst kept a journal of what he heard, saw and felt. The resulting volume, Willie’s Bar and Grill (2003), is a thoughtful road diary of one of the Oils’ final tours before they first fell silent in 2002. It includes this, written on a post-gig drive from Milwaukee to Chicago:

Herein lies the dilemma

When I play in this band my back aches,

my lungs gasp, my throat hurts.

When I don’t my brain hurts

I’ve found over the years that, FOR ME, it’s better

to punish the body than the brain.

I read this aloud to Hirst and his wife at their kitchen table in Byron. Holland suggests that “brain”, in this context, is interchangeable with “spirit”. Hirst says that, terminal cancer notwithstanding, he believes the body is more resilient than the mind. “Yeah, I would still agree with [those words]. I meant ‘punish the brain’ in that I was prone to – amongst lots of things – depression,” he explains. “As long as there was a goal, forward movement, ambition and ego, then you could get to the next point. Isn’t that what John Lennon said?”

He cites the famous Lennon quote, Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans. “I think that’s actually very true. It’s what you do every day: you make plans for something else.”

It had been a visiting US university lecturer who first opened Hirst’s eyes to social justice matters, which fed the band’s early songwriting. Garrett wrote in Big Blue Sky: “Were we earnest and self-righteous? Yes, we were.” But it all kicked up a gear in the desert on the 1986 tour, and the band’s subsequent album, 1987’s Diesel and Dust sold more than three million copies in 10 countries, including one million in the US – led by the opener Beds Are Burning, co-written by Hirst, Moginie and Garrett.

Hirst met Holland at a Farm gig in Sydney in the late 1970s. They have two daughters: Alexandra (Lex), 39, who works in book publishing in Sydney, and Gabriella (Ella), 35, an artist and writer in Berlin. The girls would occasionally join their dad and his mates on tour. After the Oils wrapped in 2002, and amid a period of growing restlessness culminating in Garrett’s exit to federal politics, Hirst continued writing and recording with acts including long-running blues combo Backsliders, Ghostwriters and surf-rock instrumental group The Break.

So far, all pretty smooth for a rock’n’roll life – or so the fans thought. In 2010 it emerged that, at the age of 17, Hirst had fathered a baby with his 15-year-old girlfriend, and the pair had taken the advice of their parents to have the child adopted. That child, Jay O’Shea, went on to become a country music artist in Tennessee. After reaching out to her birth mother, she found Hirst. O’Shea, now 51, told me back in 2020: “I felt like I was meeting a friend – and I often feel like I’m hanging out with my friend, which is really lovely.”

After a 15-year hiatus, the Oils were back touring the world again in 2017. Albums followed, supported by more touring in 2019 and 2021, then the final curtain. O’Shea was thrilled to watch Hirst perform on the Oils’ victory lap; the pair wrote and recorded a duet album, The Lost and The Found.

When it came to breaking the news of his cancer to those closest to him, Hirst would tell all three daughters of his diagnosis on the same day, shortly followed by his bandmates.

“I think stony silence can be your best friend ... 50-odd years of Midnight Oil is a great testament to that.” So said Hirst in a 2022 interview with me to mark the band’s farewell. Such was the band’s solidarity that they never aired grievances publicly – in fact they rarely vented at each other behind closed doors, either. Forging their own creative path with minimal record label intervention, they famously declined an invitation to the Grammys to attend a political event back home.

But while the path of staunch independence may have helped the Oils’ longevity, Hirst has also described it as “counter-productive”. You see, life has taught him that stony silence can also mean pain.

Hirst’s father Peter had fought the Japanese in Papua New Guinea but never shared his experience – until one day the truth poured out. In between tours Hirst used to visit Magnetic Island, offshore from Townsville, to see his parents who spent winters there.

On one occasion, he recalls, “we walked across the mountain on Magnetic Island... It must have reminded Dad of the jungles of New Guinea. For the first time he opened up, and he told me more about his regiment and what he did in the war in a two-hour trek than he’d ever done – and never mentioned it again.” He adds: “I was kind of, ‘F..k, where’s my notebook?’, because I always carry around a little Moleskine. I was just trying to remember all this stuff.”

When Peter died, Rob and his younger brother Matthew, sorting through their father’s belongings, came across a locked metal box. Inside was a mystery: Peter’s military records, including his mobilisation and demobilisation papers, wages, awards, his slouch hat and colours. There was also a large silk flag bearing the Japanese rising sun and about 70 Japanese signatures – names he later gleaned were soldiers signing off before what was maybe their final action.

“Why did Dad have it?” Hirst says now, eyes wide, shaking his head. “What didn’t he tell me on that walk on Magnetic Island? None of those servicemen ever spoke about any of this stuff – and now, of course, it’s too late.”

Some secrets might be worth keeping in a locked box until you’re dead, but Hirst’s illness isn’t one of them. “I wanted to get the story of pancreas cancer out there, because it’s one of those cancers that most people don’t really register,” he says. “It hasn’t really attracted the attention, for example, of skin cancers or breast cancers or others – but it’s really on the rise [nearly 4000 people in Australia died of it last year]. People are doing their best; unfortunately, immunotherapy doesn’t seem to work for pancreas cancer, yet.

“Coming up to two years, I thought I just need to get this, literally, off my chest. Also, I think that the lesson for me – and maybe why I’ve lasted this long – is because, if you do have any of that kind of symptom, where there’s something that you feel is wrong, just go and get a simple blood test. It could be life-changing, and life-extending.”

Hirst found a fellow traveller in Mark Moffatt, producer of The Saints’ album (I’m) Stranded and another 15 ARIA Hall of Fame inductees, who had also been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. “We were chatting all last year, comparing notes: ‘What drug have they put you on? How are you feeling?’” recalls Hirst. “He was five years older than me but very fit; still running. We were calling each other, and he was telling me about the new album he was making with Swanee [John Swan].”

Hirst was dismayed to hear in September that Moffatt had died, aged 74. They hadn’t spoken for a couple of months and he hadn’t said goodbye, or thanked Moffatt (who lived in Nashville) for his friendship. “So one of the reasons I wanted to talk about pancreas cancer is to honour Mark,” says Hirst. “There’s so many people whose lives he affected; one of the great musicians that worked with everyone.”

Another death, too, is on his mind. Five years ago, Bones Hillman, who had been Midnight Oil’s bassist since 1987, died of lung cancer at 62. Hirst had spent decades hearing Hillman’s voice in his onstage foldback wedge, pitching his voice to the sound that was always “right on the note”. I assumed the band had been keeping Bones’ condition confidential for some time and I said as much when I spoke with Hirst on the phone a few days after Bones died in Milwaukee in November 2020. I was wrong.

“Bones was actually keeping a terrible secret from us,” Hirst said at the time. “We think Bonesy knew something was wrong a long time ago, but being the amazing, independent Kiwi that he was, he didn’t want to burden anyone else… and that’s why it appears to people that it happened really quickly.”

Tears come as Hirst recalls a powerful moment in the 2024 documentary Midnight Oil: The Hardest Line, directed by Paul Clarke. Titles on the screen tell the audience how the band’s album The Makarrata Project went to No.1 on the ARIA chart – and then the next day, Bones Hillman died. Hirst recalls sitting alongside Garrett and guitarist Martin Rotsey at the premiere and his eyes well up.

We’ve been talking for hours and Holland has stayed close by, making ham and salad sandwiches for lunch, and chiming in with the occasional comment. She clocks her husband’s tears in a flash and proffers a tissue. He wipes his eyes and takes a few moments to recover.

Hirst says he wants to do things differently. “Regardless of how Bonesy was, I’m a believer in modern medicine. I’ve always believed in the people looking after me, you know?”

Holland, 69, has watched the arc of Hirst’s career. I believe this is the only time she has participated in any of the hundreds of interviews he’s given. “Everything was based around the Oils; they took all our time,” she says. “But I think that last run – that last seven years, when it all came back – was a gift. It was so remarkable that I kind of forgave them. Which is strange. But it was very consuming. It had to be.”

She has own experience with cancer to draw on. “Breast cancer is very well funded and known; I had it 20 years ago,” she says. “But people don’t generally live long enough with pancreas cancer to get organised; that’s why it’s really underfunded and unknown.”

I ask Holland how the past two years have been for her. “Very difficult,” she replies. “He’s sort of ‘the man least likely’, I always think. How? When someone’s so fit, so healthy, so invested in staying healthy and eating the right way – how does that happen?”

“It’s really great, by the way, not eating ‘the right way’ now,” Hirst chips in, noting his fondness for the likes of dark chocolate fudge and the Mini Magnum ice creams. “And it’s stuff I’m allowed – nay, encouraged – to scoff now,” he marvels. Hirst’s close friends and family have showered him with love and support but he has special praise for his wife: “It’s worse for the carers, but she’s been this tower of strength through the whole thing. Amazing.”

Says Holland: “It’s been a hard two years – but it’s been two years. A lot of people die within a week. We’ve done pretty well.”

Hirst and Holland bought their Byron Bay getaway, affectionately known as the Fibro Majestic, in 1997. He opens a door and steps out onto a balcony facing a spectacular ocean view. My jaw drops. “It’s something, isn’t it?” he says.

Beyond his backyard is the dense bush of Arakwal National Park, then the wide sweep of Tallow Beach, and Cape Byron Lighthouse. “Without getting too, you know, ‘bamboo pyramid’ about everything, I’ve always used this place as a retreat, as something that nourishes the soul and the heart,” he says.

Following four months of chemotherapy, in September 2023 he underwent an eight-hour “Whipple” surgery in an attempt to remove the primary cancer. “Basically, they re-plumb your entire insides,” he says. “They take out part of the pancreas, small intestine and liver – and then they replumb you, and hope to hell it all holds together.”

His anaesthetist was a huge Midnight Oil fan and chatted about her favourite gigs as Hirst went under. He awoke with a zipper scar down his chest, among other discomforts: “A tube up the willie, tube in the nose, tube in the side, tubes in the neck,” he recalls, grimacing. “I’m lying there like a big piece of meat, and I think, ‘Oh, at least that’s gone; that’ll give me some time.’ No: the surgeon came in. ‘Sorry, Rob, we couldn’t get it. Too close to the blood vessel; there’s a good chance you’d bleed out on the slab. So we took out a couple of dodgy lymph nodes and sewed you back up. Sorry.’”

That was the toughest day in the past two years, he reckons, because it extinguished the hope of excising the tumour.

Months of chemotherapy followed, which kept his markers at a low level, indicating the cancer hadn’t moved into other organs. Then radiotherapy, which involved being inserted into a big machine at Royal North Shore Hospital for about 15 minutes a day for five weeks, complete with a soundtrack. “They saw me – a man of a certain age – and instinctively put on U2. After three days I was sick of Bono and co,” he says, cackling. “I said, ‘Have you got The War on Drugs? Have you got Gang of Youths?’”

The treatment has been punishing, but then so was drumming in a rock band. Hirst has described how he used to “lay on the bed groaning” after gigs, and the weeks of recovery following the Oils’ final tour. “I haven’t got the breath power to play drums anymore, or at least not the way I could – and if I can’t the way I could, I won’t,” he says, decisively. “I did that for 60 years, so I’m not really missing out on anything… I’ve been so lucky.”

He does hope to one day play guitar, stomp and sing again with Backsliders, he says. His oncologist, Professor Stephen Clarke, doesn’t count it out.

“Rob’s got probably a more favourable version of pancreas cancer, because he’s now two years down the track from diagnosis, and it hasn’t spread to other places at this point,” he tells me. “It’s still probably going to kill him in the long run, but we hope he’s still got a fair bit of time left in him. The average survival for his stage cancer is in the region of six to 10 months. The fact that he’s still alive and going on holidays and doing things two years down the track is a pretty good result.”

Clarke and his colleagues see nearly half of all pancreatic cancer patients in NSW. “People tend to get written off when they say they’ve got pancreas cancer … because the outcomes are so bad,” he says. But that’s the wrong way to look at it, he believes. “We should be looking to do everything possible… because there’s data from overseas that, if you treat more pancreatic cancer patients, your outcomes are better.”

Clarke, 66, adds: “I’ve looked after a few pop stars over the years, and Rob is the most erudite, clever and pleasant of all. He’s got a sense of humour which is almost as black as a medical oncologist’s, and so we muck around and make jokes, and hopefully lighten the tone of the interaction.

“He’s done better than expected. We rejoice when [patients] are doing better than average, and just encourage them to keep going.”

The following morning, Hirst is out the front sweeping leaves from his driveway. I’ve come bearing a box of Mini Magnums. He greets me with a wave and a broad smile. Lesley took a flight back home to Sydney earlier that morning, and he’ll follow her tomorrow – but for now it’s just the two of us, and we retreat inside.

There’s a few more things I want to know for this story, so that I can tell it true. And one of them is about Hirst’s mother, Robin, who worked as a stenographer for a law firm in Sydney and battled chronic depression.

“I think my mother could have been a published author – if I have any talents in the writing department, they come from Mum,” he says. “Throughout the entire Oils touring, she sent me the best letters – they’d be waiting for me in hotels. That meant a huge amount to me, her letters, which were always perfumed as well, and beautifully constructed. Her grammar, syntax and her expression was always just absolutely perfect.”

Robin’s bouts with depression manifested when the three Hirst brothers – Stephen, Robert and Matthew – were growing up in Campbelltown. “We didn’t realise at the time, but she was having, I think, a series of nervous breakdowns,” he says. “But this huge light went on as soon as we got to Sydney; she made new friends.”

Yet in 2012, aged 85, Robin Hirst “attempted to take her life three times by drinking different toxic substances – and the last time, she succeeded,” he says quietly. “You can imagine how awful that was for Dad, calling ambulances that took other calls before... I mean, to get to that point where you just don’t want to be around…”

He trails off, then returns. “One of the last things she managed to utter to me as she was dying was, ‘Don’t grieve for me.’”

The loss is still unfathomably deep. “We all adored Mum; she was just the biggest-hearted, [most] generous, supportive person.”

Hirst’s grandmother died at 103, and his father at 91. But Hirst is content with his lot.

“It’s been absolutely better than anything anyone could ever ask for,” he says, smiling. “And so, if my life is attenuated by this tiny little tumour that threatens to do me in, then I will still consider myself incredibly fortunate.”

Voluntary Assisted Dying, legal in NSW since 2023 for eligible adults, is something he supports. “Very much so,” he says. “This year or next year – whenever it’s my time, if I need to, I will take advantage of that. Why should you have to die in terrible, drawn-out pain?” he asks. “When you’ve had this amazing life – a life like I’ve had – why should end-of-life be so horrific when there’s an alternative?

“People wouldn’t let a dog die in terrible misery; they put them down. Why should humans have to go through that?”

Is any part of him scared? “No, not about shuffling off the coil. I wouldn’t want to be in any pain, or that it couldn’t be controlled by some of the strongest painkillers available. I mean, having said all this, as I get closer – over the next weeks, months, whatever – I might change my mind slightly. But now I’m feeling fairly robust, that’s how I feel about it.”

I ask Hirst how he’d like to be remembered. “From a musical point of view, I would like to be remembered as someone useful to have around a band,” he says. “I really like that term useful, because in a way it encapsulates what we should be doing with our tiny little, microscopic time on the planet... Were we in any way useful, for the planet? For people? For friends? For loved ones?”

He’s intent on spending his time in the ocean, and strumming his Gibson J-50 acoustic guitar, and puzzling over songwriting. He’s also got a few writing projects, including marshalling a collection of his lyrics spanning 50 years, and a novel for young adults. But after a lifetime of work he’s careful not to spend too many of his remaining days immersed in it.

Instead, he wants to be around his loved ones. He sheds tears of gratitude at the support of those he loves as well as the team of healthcare practitioners who have kept him alive, and then laughs as he likens his present situation to that Seinfeld episode where Jerry ends up in the first-class cabin on a plane, enjoying the flight attendants’ largesse. More anything? “More everything!”

He says he wants to meet his next grandson – Lex’s second child – who’s due in July, and he’d like to have another birthday in September because it’s a good opportunity for a party. But if the clock stops before meeting either of those milestones, so be it.

Meanwhile, he’ll be admiring the humpback whale highway that passes by the Fibro Majestic in winter, scoffing Mini Magnums with Lesley, enjoying the love of his children and grandchildren, and smiling at his good fortune – all while he’s busy making other plans.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout