Peter Garrett on the failure of the voice referendum, protecting Cape York and healing old wounds

Hit with a ‘thunderbolt from hell’, the ageing rocker and progressive ex-Labor MP’s central role is now as a patriarch. In a rare, almost unheard-of public foray, we hear from the women in his life.

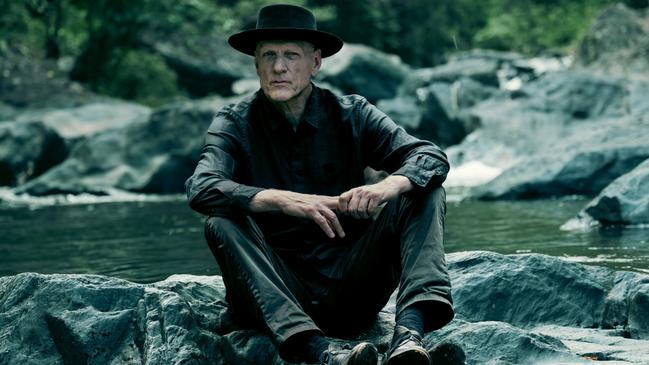

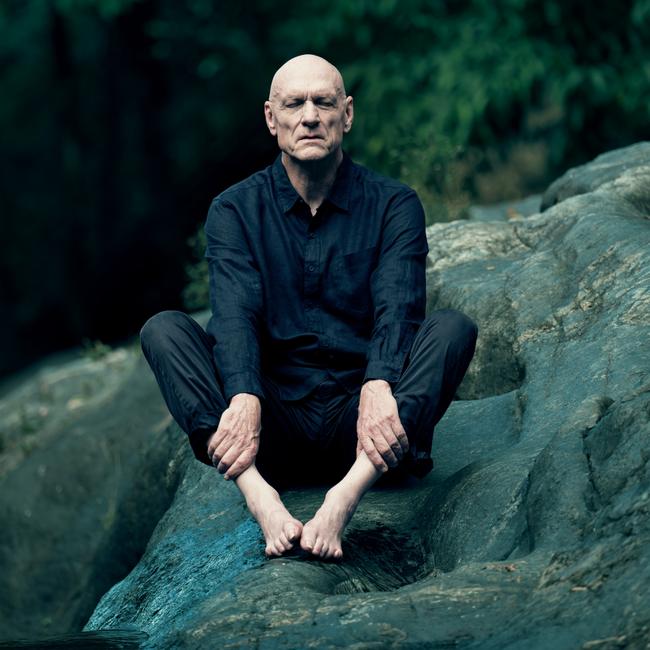

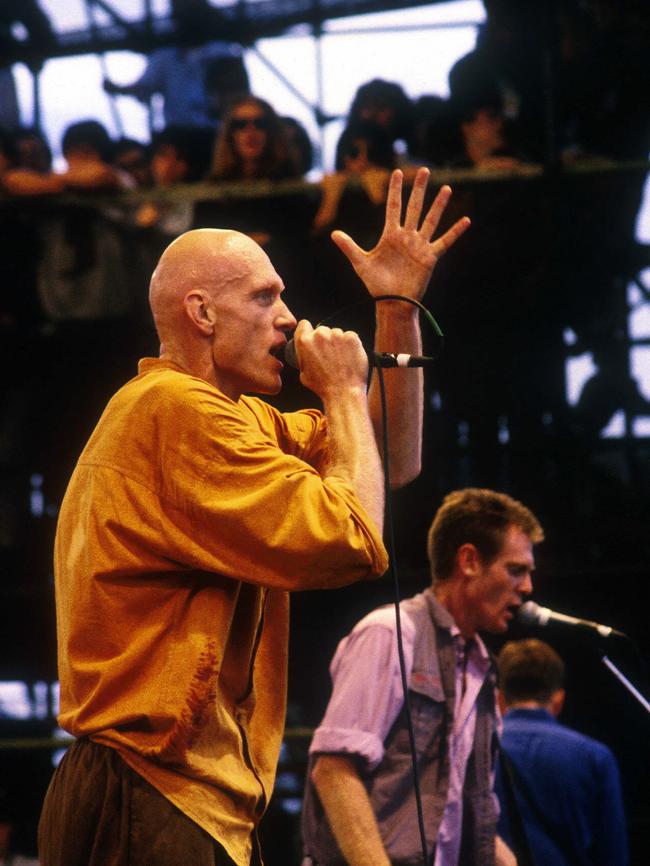

Peter Garrett doesn’t bring much to band rehearsal. That lanky frame, bald dome and the instrument in his throat. OK, maybe sometimes a microphone, too, and today a black hat that’s hung on a stand behind him. This is how it’s always been, across the decades of his storied career. It’s his bandmates who haul the drums, guitar, bass, keyboard and amplifiers, supervising their setting-up and carefully checking all is in order. Only then can the music begin.

We’re in studios in Sydney’s Alexandria. Garrett stands in the centre of the space, wearing that familiar Cheshire cat grin, and says apologetically: “Prepare to be deafened – and bored.” It’s a wry acknowledgment of both the stop-start repetition of rehearsal and the noisy textures and tones that his band The Alter Egos are about to produce.

Garrett is facing drummer Evan Mannell, flanked by bassist Rowan Lane and keyboardist Heather Shannon. Martin Rotsey stands to his left; the trusty, stone-faced lieutenant formed half of Midnight Oil’s distinctive two-guitar attack and was Garrett’s sounding board on his 2016 solo debut and then its follow-up.

“Why don’t we have a lash at The True North?” Garrett says to the others. He’s talking about the title track from his upcoming second album, a nine-track collection which, on this Wednesday in early November, is still a while away from official release. The band is here to rehearse a few new and old numbers for a smattering of warm-up shows ahead of a full national tour in the new year.

The True North album is ostensibly why I’m here, but there’s something bigger at play, and there are clues in the name. Reporting for this profile will take me to Cairns – where Garrett is quietly lobbying hard for the protection of vast swathes of Northern Australia – and back down the east coast to Kangaroo Valley, which he calls home. Along the way, Garrett’s own true north will be laid bare: that which guided him from law student to rock star frontman of Midnight Oil, to federal cabinet minister, to his farewell shows with the Oils – and now, this later-life solo career. It’s a journey that has spanned 70 years. Along the way there have been some key constants; in a rare, almost unheard-of foray speaking to media, The Weekend Australian Magazine will hear from his wife of 37 years, as well as his daughters whose vocals appear on The True North. But for now, Garrett is singing …

Beware the south’s errors or remake them

From Cape to Kimberley via Madjedbebe

It’s the oldest living story

Rent asunder by brute authority …

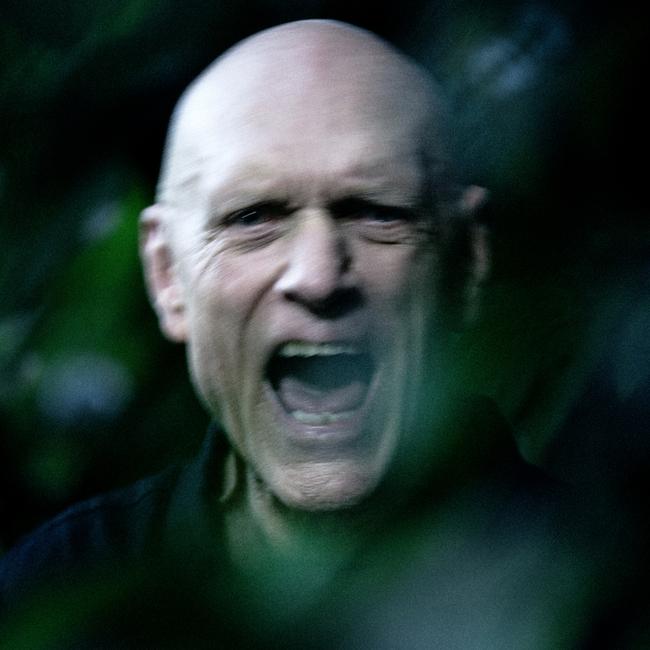

Think he may have mellowed with age? Not a chance. The lyrics on this new album are as powerful and urgent as ever, and Garrett somehow finds new gears to sing them.

Rotsey switches from a maroon Gibson SG to a cream Telecaster, and plays with his eyes shut, lost in the music; Mannell deploys restraint, grasping a mallet in his right hand and a steel brush in his left. “Do you want to do it again?” asks Lane at the end of the song.

Garrett replies that he does. “It’s gonna be good,” he says – a command and a forecast.

Second time proves a charm. “That’s better,” he says, smiling. “Nice and full.”

Then he announces: “Time for us to have a cup of tea, what do you reckon?” On our way to a cafe inside the rehearsal complex Garrett stalks past a closed door where Ian Moss and his band can be heard rumbling through his Cold Chisel classic Bow River ahead of some regional Victorian dates.

Garrett takes a seat beside a glass counter displaying biographies of Neil Young and Anthony Kiedis. When Garrett turned his life story into a book in 2015 he wrote it himself, which is unusual for the genre. He took the job seriously – Big Blue Sky is one of the most engaging and beautifully realised accounts of a life written by an Australian public figure.

The steel-trap mind is on display as we chat. I remind him I’m from Bundaberg and he’s quick off the mark. “Oh yeah, Bundy? You’re up in No vote territory there,” he says, referring to the Voice referendum, defeated a few weeks earlier. It was “a very disappointing result, particularly for Aboriginal people who had championed the Voice – but not entirely unexpected, given the fact that it was opposed very early on by the alternative prime minister,” Garrett reflects.

When we speak about it again later, he doubles down. “Mr Dutton’s act was highly regrettable,” he says, adding: “Mr Albanese probably in hindsight should have said, ‘If we don’t have the support of the Opposition leader, it’s pretty clear that it can’t succeed.’ He didn’t want to disappoint many people who felt that it should have been put anyway, including the indigenous leadership. That was probably a mistake in hindsight.”

So the timing was wrong? “Probably, in as much as the ground hadn’t been laid as to why or what the Voice actually would do, or how it would work. I mean, I got into the detail of it, as you can imagine, because it’s been a subject really close to my heart.”

The campaigning was off, too, he reckons. “For ordinary people who are getting about, raising kids, having jobs and all of that stuff, it probably wasn’t as clear as it should have been as to what was on offer.”

The first time I met Garrett was in July 2019, in the Queensland desert, when Midnight Oil was headlining the Big Red Bash music festival near Birdsville. He was up for an adventure then, leaving his jet-lagged bandmates and their partners on the bus as we stomped up the far side of the rust-coloured sand dune known as Big Red. When I ask him now how the Peter Garrett of today differs from the one four years ago, he replies: “More juice in the tank.”

I raise my eyebrows involuntarily. “Yeah, it surprises me too, honestly,” he continues. He puts the increased vigour down to a range of things: Midnight Oil’s successful tours in 2019, 2021 and 2022 and the crowds’ rapturous response; the pandemic and probably most significantly, a growing awareness of his own mortality that has “left me with this feeling of wanting to go even harder, and enjoying the music even more, and the idea of performing – nothing’s a chore,” he says.

“Life shouldn’t be a chore. It can’t be a chore. It’s absolutely unbelievable to be upright, and singing and writing songs, and mouthing off. It’s what I do.”

Not for the first time, fans are forming an orderly queue for a photograph beside Peter Garrett. It’s late afternoon in Cairns, two weeks after the band rehearsal and our cafe chat. About 60 people – a mix of traditional owners, state and federal environment ministers and their staffers, researchers, landscape photographers and environmentalists – have spent the day in a conference room workshopping the proposal from Queensland state and federal Labor’s proposed World Heritage listing for the Cape York Peninsula.

Tanya Plibersek, federal Minister for the Environment and Water, invited Garrett (who held the role of Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts in the Rudd Labor government from 2007 to 2010) to host the session. Under UNESCO rules, the governments must consult with Indigenous leaders from Cape York communities, with the final decision to be made in Paris.

All this can take years. When I ask Plibersek about recruiting Garrett to an official role in a cause with such a long lead time, she laughs and says: “I mean, I hope he won’t be dead when we achieve this victory!” Then on a more serious note, she says: “But it’s not about tomorrow, it’s about the next hundred years – and in my portfolio, it’s about the next thousand years.”

The meeting is supposed to be under the radar – a near impossible task in the gossipy north. Sure enough, a few weeks later the news leaks. Critics attack the proposed listing as a cynical and “hurried” move to take votes off the Greens in hotly contested federal seats in the south of the state, rushed through in case Labor loses the Queensland state election in October.

The listing means tight restrictions on the use of the land. Garrett’s record on reconciliation and Indigenous land rights may be strong – back in 1987 he sang in Midnight Oil’s most famous song “The time has come / A fact’s a fact / It belongs to them / Let’s give it back” – but that didn’t stop Balkanu Cape York Development Corporation executive director Gerhardt Pearson from taking umbrage with the Garrett-led consultation, saying he was not invited to the November workshop. “We were initially told that this was going to be an Indigenous-led process and now we find it is being run by a rock star … with the Black fellas sitting out on the wood heap,” he told The Australian in January.

When we discuss it later, Garrett doesn’t seem fazed by the criticism, which he declines to address. Instead he says: “We [Midnight Oil] played on every continent, and we’ve been to all these places. And even if you just fly across it in a plane, you’re looking down – and all I’ve seen over the last 35 years is the green spaces vanishing, the forests disappearing, the rivers becoming muddy, the mess just piling up. Mountain after mountain, hill after hill of mess, rubbish and toxic waste.

–

“And then I look at the top of the country that I live in, and I see something completely different, and I realise how important and how precious it is. And I think, ‘Well, I’ve got the breath. I’ve got the time. I should jump in and stir the possum.’ What kind of citizen am I, if I don’t pipe up and try to do something about it?”

–

To use the term “rock star” as a pejorative doesn’t quite suit Garrett. None of its connotations of excess, disorder or questionable behaviour hold true for his path through life, which has been marked by a preference for hoovering up stacks of paperbacks in bookstores rather than lines of white powder in nightclub dunnies.

“He is the anti-diva,” says Tony Buchen, who produced Garrett’s new album. “He’s ultimately a very considered, kind person who thinks about other people’s feelings, while also having the most sensitive bullshit metre on the planet.”

That bullshit metre was on display last month during Taylor Swift’s Australian tour. In an Adelaide radio interview Garrett took issue with her ticket prices, accusing the biggest pop star on the planet of “price gouging, to be blunt”, adding: “The dollar end of it, just looking at it from a distance – having been in the business forever – is pretty brutal. But that’s everybody’s choice.”

It’s philosophically different from Midnight Oil’s long career in the live arena. “Our thing, and my thing,” he tells me, “has always been that if we can sustain ourselves, and do fine, then it’s not about slicing and dicing it to the absolute max – you’ve left some money for them to go and see someone else.”

The Oils have retreated into inactivity following their final world tour, which concluded in October 2022 with a marathon hometown concert at Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion. Among the true believers in the crowd that night was prime minister Anthony Albanese (whose office prominently features a framed poster of the artwork from the band’s 2020 reconciliation-themed album The Makarrata Project). “It was just extraordinary,” Albanese recalls. “They went for nearly four hours and looked like they could have gone a couple more.”

“Peter is one of the most extraordinary frontmen this country has ever produced,” Albanese adds. “It starts with the sheer physical presence of the guy. And then he opens his mouth. He sings with such power, but he can also sing with such tenderness. Everything is real, there’s no act.”

With the fan photos in Cairns finished, a small group who attended the workshop moves on to a bar at the Colonial Club Resort for a drink and a debrief. From there, Garrett and a core group of four friends decamp to a beachside residence north of the city. I’m along for the ride. In fact, I’m the designated driver.

Garrett climbs into my rented Isuzu. I’m playing Silverchair’s Diorama on the car stereo. Garrett casually asks if I’ve been given an advance copy of his forthcoming album. The next thing I know, he’s connecting his phone to play the mastered digital audio files via Bluetooth.

There’s always mix of pride and vulnerability from a singer-songwriter when they play you tracks before they’re released to the world. And this is a special moment for me. Some of my earliest musical memories are of the Oils’ Earth and Sun and Moon album blaring from my parents’ speakers as I studied the lyrics sung by Garrett, puzzling over lines like “cyclone fences in the cybernetic orchard …” (Feeding Frenzy) and “when my mother went down, it was a stiff-arm from Hades” (In the Valley). Tonight, I’m listening with the man himself.

The True North has a sonic footprint similar to the 2016 solo debut A Version of Now: firmly rock ‘n’ roll, but more gentle than an Oils album, tinged with folk, country and pop. Lyrically, though, the singer-songwriter pulls no punches, and the planet’s rising temperature is a dominant motif.

In the spoken-word second half of the song Innocence, his stream-of-consciousness narrative locks on this image: So I imagine a court of climate criminals crowded with PMs, sheiks and presidents, Woodside corporate titans – all well-groomed, best jargon. Delivering profits from frying the planet, and roasting us alive, puncturing the thin blue protection line …

In the penultimate track, Meltdown, he sings:

Got a ringside seat for the final countdown

Put Santos on the spot with the right-wing clowns, oh yeah.

But rather than getting caught up in squandered opportunities to arrest the climate crisis, the song ends with a grace note of optimism:

Meltdown is no weird fantasy

I won’t succumb to the grief

The ending is no more torching the land

So hold me, we’ll be in good company

Taking on the meltdown

Getting with the plan.

Two of Garrett’s three daughters, Grace and May, who also perform together in a Sydney indie rock band called Raintalker, blend beautifully with his tones on this track. It’s not the first time they’ve collaborated, either: on A Version of Now all three siblings sang backing vocals and toured with him in 2016.

“It was something that Dad put out there, not sure whether we’d jump at it or not, and we were all keen to give it a go,” recalls Grace, 34, of their first album collaboration. “It led us to joining him on the tour, which was a lot of fun.”

“When it came to The True North, May and I put our hands up again,” says Grace, who also designed the album artwork. “We thought, ‘Why not?’ He loves what he does, and it’s really inspiring seeing him up there on stage, knowing that he has the mentality that he has something to say, and he’s so passionate about it.”

The True North also features a track by Victorian singer-songwriter Ainslie Wills, who shares a publisher with Garrett in Sony/ATV. At their invitation, she took up the challenge of capturing Garrett’s essence in a few verses. Amid a gentle rock arrangement on Human Playground, he sings her words about him, and the effect is revealing:

Heart of a child, body of man

Speaking my truth any way I can

Push yourself so hard it hurts

See the damage in reverse

I still feel the wild inside

So I push myself to overdrive.

After Wills submitted a demo, Garrett called her to discuss the idea. “When I hung up the phone I was like, ‘Wow, this man is so vibrant, and so energetically alive’,” says Wills, 41. “That was a good one to hook into, in terms of his energy: he has lots to do and say, still, and he’s as passionate as ever. Which is so inspiring, because as age comes upon us, the way that society is, people think you’re ‘over the hill’ and you’ve got nothing left to say – even though you’re at that point of your life where you’ve got so much experience, and so much that you want to share.”

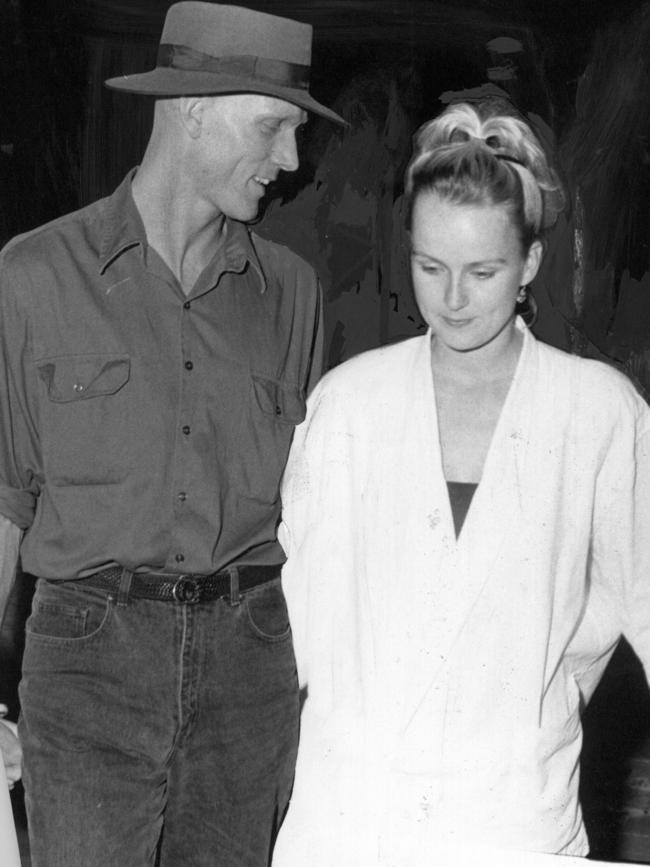

Garrett’s wife and the mother of his three daughters, Doris Ricono-Garrett, frames it this way in an email: “At almost 71, there is no doubt Peter has a greater awareness of his time limits. Having always had a highly developed social conscience, partly instilled by his mother, I think there is perhaps a more urgent need now to feel he is still contributing to making the world a better place.”

On a mild January afternoon I meet Garrett again on the main street of Kangaroo Valley, the NSW town 157km southwest of Sydney that he and Doris Ricono-Garrett call home.

Two months after our Cairns adventures, our roles are reversed, with him in the driver’s seat. He shows me the local sights, including a couple of jaw-dropping lookouts that take a bit of bush-bashing to reach on foot, and the showgrounds at the nearby town of Nowra, where Midnight Oil – then known as Farm – played decades earlier, in 1973.

Looking through the windscreen at an unremarkable hall where a brief chapter of Australian rock history was written, he recalls: “It was three bucks [to get in], and one of the boys’ school mates was on the door. I’m pretty sure it was gig number two. I can remember sleeping in our cars out the back there, under the gums, then waking up in the morning and thinking, ‘OK, that was interesting. Now, where are we going?’”

Where they were going was unknown, but in a coin-flip between immortality and anonymity, the odds were likely that they’d be just another band who played a few shows together before fizzling out and going their separate ways. “No, that was never gonna happen,” he says firmly, as he steers his car back onto the bitumen and away from the ghosts of his past.

Oh yes. The past.

Two years ago, while writing a story on Midnight Oil’s final tour for this magazine, we sat in the shaded courtyard of a Launceston hotel and I pressed him about In The Valley, a 1993 song that told the story of his family spanning several generations. He didn’t want to talk about it. “You should really never explain your songs and how you work,” he had said.

Now, in a back room at Kangaroo Valley’s only pub, the aptly named Friendly Inn, over dinner and drinks (where we’re interrupted only a couple of times by locals saying hello and asking for a photo with him, which he happily obliges), I ask him again about the song, whose lyrics mention the death of Garrett’s father and mother. Peter senior “went down with the curse of big cities”, suffering an asthma attack in 1971, the year Garrett went to ANU in Canberra to study Arts/Law.

His mother Betty, who was among the earliest generations of women to graduate from Sydney University, “went down with a stiff-arm from Hades” – a reference to the Lindfield house fire in which she died in 1977, when he was 23. Garrett tried to rescue her from the flames, but was unable; the coroner was unable to ascertain its cause.

How does he carry that night with him after all these years? “Look, everybody’s got a different way of dealing with grief on that scale,” he replies. “At the time, and even in retrospect, it seems like a bit of a thunderbolt from hell – but there’s plenty of thunderbolts from hell hitting people everywhere. So I think that on reflection, you’re sort of half-conscious when you’re going through it, and you just put one foot after the other, which is what you need to do. Over time, you recover your balance, and a bit of equilibrium, and you go on from there.”

It helps in the wake of such a cataclysm, he says, “if you feel as though you’ve been well-loved as a child.”

“I think in any person’s life, that equips you as well as anything can for whatever you’ve got to deal with,” he says. “I’ve always said I was never going to parade it and spend a lot of time swimming around in that pool, because I hold her memory so dear, and I want to honour them.”

Garrett and his younger brothers, Andrew and Matthew, were brought closer in the wake of the tragedy, and have remained tight ever since. “We do have something which is what feels to me like a binding that holds the relationship together, which couldn’t be broken.”

In Big Blue Sky, his imagination ventured to his own ideal send-off, and when I ask him about his imagined funeral, he replies: “I’m not fixated on mortality, although I’m obviously well past halfway. It’s very clear to me – and I think it’s dawning on many of us – that the old Victorian, laced-up, semi-religious, dry, mournful, sorrowful rituals of farewelling people do not do people’s life justice at all.”

His parents never got to see what their eldest son became: musician, activist, husband, father, politician. “But neither did my wife’s parents get a chance to see what she became, or what happened to her, either,” Garrett offers. Yes, but we’re talking about Peter Garrett here. “I try deflection every now and then,” he responds with a smile, although it’s obvious he’d like to move on from this line of questioning.

Is it doing his parents proud that drives him? “I don’t project to that, particularly,” he says. “I’d like to think that they would be proud of some of what I’ve done. They might have disagreed with some of it; they might have celebrated other parts of it. They certainly would have been proud of ‘success’ in the conventional sense. I mean, my mum came to a very early Midnight Oil performance, and loved it – but never knew, like we didn’t know, where it was going to end up.”

Where he has ended up is not just a “rock star” or even a moonlighting environmental lobbyist, but the patriarch of his own, deeply loving family. For Garrett, the sun rises and sets with Doris Ricono-Garrett, who he married in 1986. She is his “only one”, as he described her in a 2016 song.

In an email, Ricono-Garrett writes to me that parenting their three daughters has shaped and changed her husband over the years. “After the early deaths of his parents, I believe his new family provided him with the emotional frame and balance he needed to perform in his various ways in public,” she writes.

All that Garrett brought to their life was himself. His family bring the instruments.

“I love the fact that he runs his ideas by me from time to time,” his wife adds. “I would say that over the years, our daughters have also helped to introduce him to new horizons, be it creatively in terms of new music, new gender politics, new technology and new promotional (social) media.”

It’s dark outside the Friendly Inn when Garrett and I empty our glasses. Only a handful of stragglers remain, yakking loudly and occasionally troubling the bartender for refills. As we pass the throng, Garrett exits with a wave of his large hand, his five fingers outstretched, like the iconic logo of his famous band circa 1978. For me it’s a short walk to my hotel; for him, a short drive to his hideaway nearby, somewhere near the main drag of this tiny, pretty town. Away from the spotlight, he’ll continue working on some unfinished business, including the World Heritage matter up north, and plenty of other hush-hush projects that this time will stay secret.

Up ahead in the distance, he’ll grow old with his sweetheart in the valley, and they’ll continue watching with awe as their girls become formidable women. But first, what will follow this midsummer’s night is the release of a remarkable nine-track album – a new artistic statement from a towering figure of Australian culture, with performances too, all delivered at full bore under bright bulbs.

I dig out that reference from his memoir when his mind forecast his own ideal send-off: “Just put the music on and dance like there’s no tomorrow,” he wrote. “No breast-beating or self-pity, no howling at the moon. Keep me close to my girls and scatter my ashes across the water. Leave a few morsels for the bush, but no sombre, sad funeral for me, please – and don’t forget to have a laugh.”

The True North is out on March 15, via Sony. Peter Garrett’s tour begins in Newcastle (March 12) and ends in Brisbane (March 30), followed by a Byron Bay Bluesfest performance on March 31.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout