Interview: Anthony Kiedis on 40 years of Red Hot Chili Peppers, rock ‘n’ roll’s surprise survivors

Love, drugs and brotherhood: singer Anthony Kiedis reflects on four decades of music ahead of the band’s Australian tour — its first with guitarist John Frusciante since 2007.

After all they had been through, on stage and off, there was a moment about four years ago when two musical brothers looked at one another and spoke the pure, unadorned truth.

It arrived when the artist known as Flea – the Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist born Michael Balzary – was hosting guitarist John Frusciante for dinner at his home in California.

Despite the freakish mind-meld that had seen this duo become lauded as two of the greatest musicians to ever play their respective instruments, at this time they were nothing more than old friends catching up and reflecting on times passed.

Twice before they had been bandmates who were successful at the highest levels of popular culture. Twice before, in 1992 and 2009, Frusciante had packed up his guitars and parted ways with the Los Angeles rock group, a decision that pained all four members on both occasions.

After dinner, while their girlfriends were talking in another room, Flea ventured a statement, unsure of how it would be received. “Sometimes, I really miss playing with you,” the bassist told his friend, and as soon as he spoke the words he was unable to stop himself from sobbing and crying.

As Flea met his friend’s gaze, he saw tears welling in his eyes. “Me too,” said the guitarist.

This was an exchange of love, coloured by a deeply shared history and the effortless connection that both men had first recognised more than 30 years prior, when Frusciante was asked to join his favourite band in the world.

But in early 2019, when Flea took that risk in his home of speaking his emotional truth, and his old friend tearfully reciprocated, it set in train a series of events with global consequences – not least of which was the fact the Chili Peppers already had a well-established six-string player on board.

His name was Josh Klinghoffer, who joined in 2009, as the band’s eighth guitarist overall. While he was respected as a player, he never quite had the special sauce of his predecessor, nor the fretboard fireworks. Very few of the songs the band created for the two albums issued in this era – titled I’m With You (2011) and The Getaway (2016) – had the cultural stickiness of what came before.

It was a heavy burden: Klinghoffer was tasked with following a man widely acknowledged as one of the greatest living rock guitarists, a true sonic innovator whose hands, ears and harmony vocals helped craft songs that have been FM radio staples for decades.

When the band shared the news in December 2019 that Frusciante was in – for the third time – it was met with joy by millions of fans worldwide, who had longed to see him return to making music for the masses.

While announcing Klinghoffer’s departure, the band thanked him for a decade of service, writing on social media: “Josh is a beautiful musician who we respect and love. We are deeply grateful for our time with him, and the countless gifts he shared with us.”

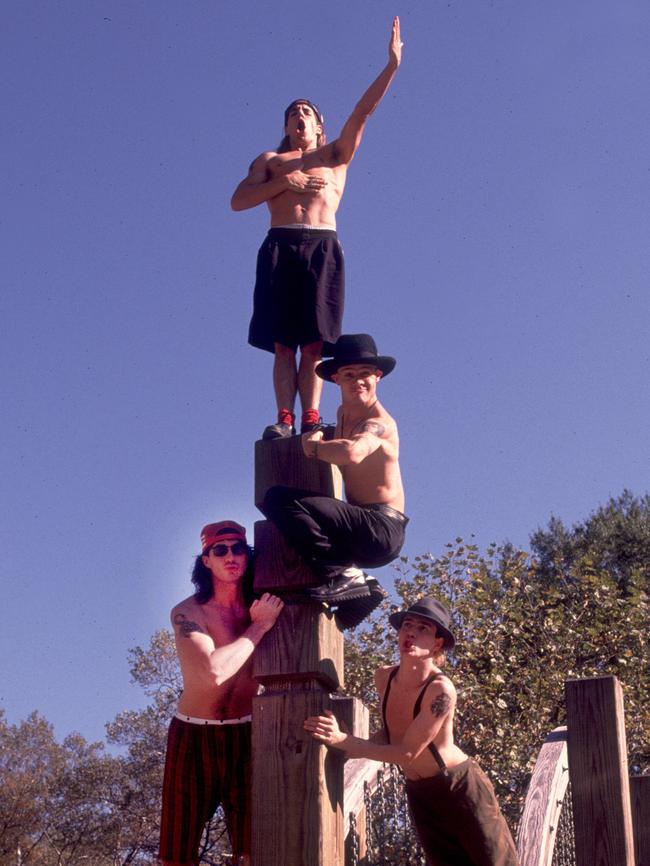

Today, Red Hot Chili Peppers – completed by singer Anthony Kiedis and drummer Chad Smith – is one of few rock bands on the planet capable of filling stadiums, which is what it will do this month when the group returns to our shores for six concerts.

Against considerable odds, the band will this year celebrate its 40th anniversary, having survived more than its fair share of turmoil since forming in Los Angeles in 1983.

Asked whether he has any plans to celebrate the anniversary, Kiedis laughs. “No,” he tells Review. “No plans to mark the occasion, other than maybe to sit there and smile at Chad Smith, or give John a hug, or make some wise crack to Flea. I don’t really celebrate anniversaries too much: I’m one foot in today, and one foot in dreaming about the possibilities of what tomorrow might hold. I’m much less interested in keeping track of the days, weeks, months, years that have gone by.”

On a phone call on Wednesday from the North Island of New Zealand, between two stadium concerts there, Kiedis says, “I do recognise it as a special accomplishment. But somewhere along the way, it wasn’t really about striving for longevity, it was just about making the most of the experience, and trying to figure out how to coexist and co-create, and stay healthy and vibrant, and do something that excites us. The fact that 40 years have passed is just a little abstract and bizarre, and not something to really dwell on for us. I would say I’m more excited about playing a show in Brisbane, than I am about celebrating a 40-year mark.”

In a podcast interview last year around the release of the band’s 12th album, Unlimited Love, Flea said to longtime producer Rick Rubin: “I still care so much. Ultimately, for us as a band, that’s what really matters: we still really care. If this thing that we do was at all just as a means to an end – to have to put out a record so we can do a big tour, so we can have a hit, or get this or that – we’d be f..ked.”

“There’s no way we’d be doing anything important or relevant in any way,” said Flea, in a conversation that also uncovered that opening heart-to-heart anecdote with Frusciante. “But because we care deeply, not only about the quality of the thing, but about the quality and the meaning, and the purpose and the process of making it … when we go in to work, this is a sacred ritual.”

It speaks to Frusciante’s musical influence that his involvement offers the clearest lens through which to tell the band’s story, despite Flea and Kiedis being on board as founding members since 1983, when the group first performed a one-song set at a tiny venue.

Some talents, though, are too big to ignore. As Flea told Rubin: “I remember him telling me, ‘I’m born to be the guitar player in the Red Hot Chili Peppers. I’m the guy that’s supposed to be in this band. That’s just the truth.’ ”

When Frusciante joined in 1988, it was in the shadow of a tragedy: the group’s founding guitarist, Hillel Slovak, had died earlier that year, aged 26, of a heroin overdose. His bandmates were devastated, and drummer Jack Irons quit amid the chaos, thereby allowing Smith to audition.

An uncompromisingly hard-hitting player who is central to the band’s sound, the much-admired percussionist has occupied the seat behind the kit ever since. “I want the band to feel really confident and know that they can look back (and think) ‘This guy’s got us’,” Smith told Rubin in a separate interview for the Broken Record podcast last year. “That’s really important to me.”

Aged 18 in 1988, Frusciante possessed a sublime sense of melody and a superb ear for building on the band’s established bedrock while gently pushing it away from its punk-funk roots toward classic rock ’n’ roll arrangements.

With the teenage prodigy on board, the group was soon elevated to playing at large venues, particularly once its fifth album, 1991’s Blood Sugar Sex Magik, caught fire off the back of singles such as Suck My Kiss and Give It Away, which were hits in a decade when alternative rock reigned supreme.

“There’s a feeling of comfort for me with Anthony and Flea that I really don’t have with anybody else,” Frusciante told Rubin last year. “I think it has to do with so many things; with going to that depth of musical connection at so many different times. It might also have to do with going from being a club band to playing arenas together, and nobody but us shared that experience.”

Produced by Rubin, one of the keys to Blood Sugar Sex Magik’s substantial success as an album was its 11th track, a ballad titled Under the Bridge that was unlike anything the group had produced previously.

It remains an undeniable feat of songwriting: an instantly identifiable and universally understood longing to connect with other people while feeling isolated. Accompanied by Frusciante’s emotive chord choices and Kiedis’s beautifully written lyrics, it remains the band’s most popular song, with more than one billion streams on Spotify alone.

In a 1991 documentary titled Funky Monks, which captured the album’s cloistered recording process in a Los Angeles mansion, the singer described the crux of the song as being rooted in feelings of loneliness.

Then three years sober, Kiedis reflected on the lowest point in his life, when he was homeless, friendless and out of touch with his family, and reduced to spending time with fellow addicts to stay well. To the camera, he sang its chorus:

I don’t ever want to feel like I did that day

Take me to the place I love

Take me all the way

“The place I love is where I am now,” said Kiedis in 1991. “Making music with my band, and making love with my friends, and girlfriends, which is to me the most sacred thing I have going: creating sound with my best friends.”

Reminded of this quote in the interview with Review, and asked whether he still feels that way, Kiedis chuckles. “Well, there are all kinds of places that I love; one is just sitting in the sun,” he says. “But yes. Yes. I love the challenge of doing that, and it is a place I love. I got lucky; I got real lucky. These co-workers of mine are extraordinary people, and extraordinary artists.”

Yet the quartet’s rocket ride to fame and fortune would screw with Frusciante’s head so badly that he saw no alternative but to turn his back on it all, mid-tour in Japan in 1992, leaving his band in the lurch. Unwittingly, he was leading himself down a path of ill health through severe drug addiction, wherein his body weight shrank to appear as “a skeleton covered in thin skin”, as described in a 1996 article.

After Frusciante had overcome his addictions to heroin, crack cocaine and alcohol, Flea visited his former bandmate at his home in April 1998. They listened to records for a while, then the bassist casually asked for his thoughts on whether the guitarist would consider playing with the band again.

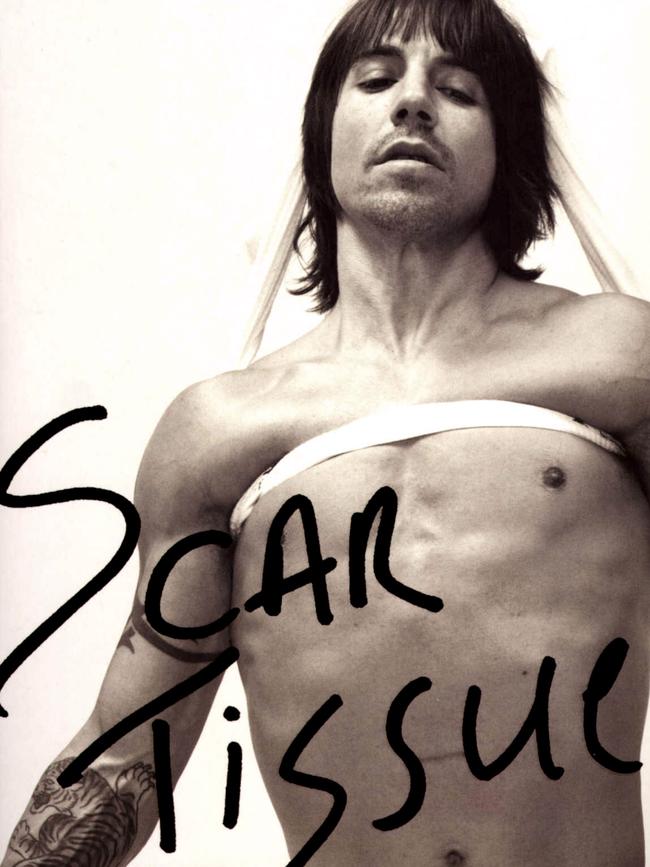

In response, Frusciante started sobbing and said, “Nothing would make me happier in the world”. They both cried and hugged each other for a long time; two musical brothers reunited, in an anecdote Kiedis relayed in his memoir, Scar Tissue.

A small hiccup: one of the world’s great rock guitarists no longer owned a guitar, a problem Kiedis swiftly solved by buying him a 1962 Fender Stratocaster.

That gift kicked off a stint that produced another commercial and creative high-water mark in Californication (1999) – a work whose cultural ubiquitousness made it akin to the Hotel California of the 1990s, which included signature songs Otherside, Scar Tissue and the title track – and then By the Way (2002) and Stadium Arcadium (2006), before the four musicians amicably parted ways again.

“I’m always aware that who I am, and every detail of my life, the result of it is that connection I have as a soul with Anthony, Flea and Chad,” Frusciante told Rubin last year. “Family is the only thing I could compare it to, but it’s so much more limited than family, because it’s really just those four people.”

The particulars of the band’s extensive history were canvassed in Kiedis’s 2004 memoir, a 464-page work composed of equal parts sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll.

While the first two ingredients tend to dominate any discussion of this book – the singer is evidently fond of detailing his many, many experiences on both fronts – it can also be read as a cautionary tale, given his well-articulated struggles to overcome substance abuse since he began seeking altered states as a child.

“The horribly ironic cosmic trick of drug addiction,” Kiedis wrote on page 96, “is that drugs are a lot of fun when you first start using them, but by the time the consequences manifest themselves, you’re no longer in a position to say, ‘Whoa, gotta stop that’. You’ve lost that ability, and you’ve created this pattern of conditioning and reinforcement. It’s never something for nothing when drugs are involved.”

When Review asks the singer how he looks back at the process of working on the book with writer Larry Sloman, he replies, “It’s something that happened at a time when it could only happen at that time. I would not do that today, but I’m glad that I was sort of dumb enough, and naive enough, and maybe full of myself enough to do something like that in 2004. You know, a lot of weird things happen when you write a book, one of which is: people might read it.”

“Larry did a masterful job of listening to me tell stories for months on end, and sculpting it into this cohesive and meaningful experience, one that actually had a better scene than I intended for it to have,” says Kiedis. “Because it ended up serving this purpose of showing people that it’s okay to struggle and fail miserably, and still emerge out of that with some kind of sanity, and some kind of love for life. My initial intention was to tell stories, but the purpose that it ended up serving was greater than my intention. So for that, I am grateful.”

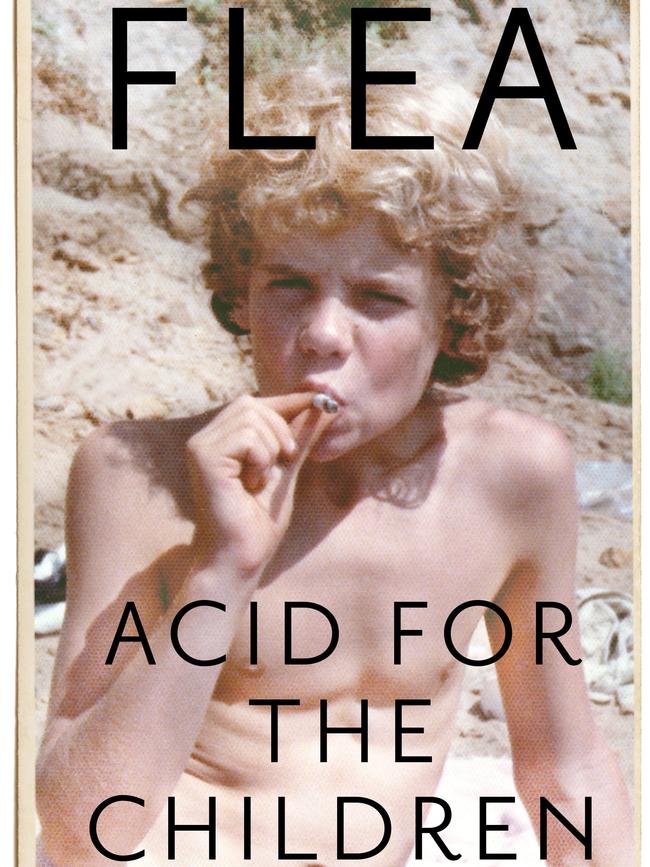

In 2019, Flea published a book, titled Acid For the Children, whose narrative ends right before the first Red Hot Chili Peppers gig. His childhood was coloured by trouble of a different sort, where an emotionally distant mother and a largely absent father left him deeply uncertain for much of his upbringing.

Befriending Kiedis, aged 15, at Fairfax High School set his life on an entirely different trajectory. “I’m so f..king grateful for his existence, for being my brother, my true family,” Flea wrote.

“When he started writing lyrics over my bass lines, his artistry gave me new life. My heart grew a couple of sizes. The colour of his words, the sharp sound of the syllables cracking together. Both his lyrics and my bass lines pulsed together, same as the heartbeat of our friendship.”

On page 92, in a brief chapter that detailed his frustrations with childhood bed-wetting, he concluded with this thought that speaks to his eternal optimism: “I still felt like I was going someplace good,” Flea wrote. “Man, I can’t even explain it, but despite the weird shit that had been going down, I still believed in a light I felt glowing within me, I was unfazed. I felt good inside, like I could rise up and fly where I wanted.”

Later, in one of the book’s many entertaining diversions from a linear narrative, the man born Michael Balzary in Melbourne, Australia, reflected on his experiences with substance abuse, and ended up singing from the same song sheet as his longtime friend and bandmate Kiedis.

“For clarity’s sake, I’ve never been a drug addict,” the bassist wrote. “A wildly out of control and misguided experimenter, yes. I thought there was something to find there, but those drugs play tricks on your brain, toying with your chemicals, your serotonin, dopamine and shit, making you think something meaningful is happening. It’s all bullshit. There is no romance there, there is nothing. Experiments that yielded sadness, neurosis, and physical damage. It takes from you and gives you nothing. Zero.”

Today, the documentary Funky Monks offers a fascinating insight into four young men flexing their creative muscles and communicating directly with one another, as they record a set of songs that, unknown to them, would go on to become their masterwork, and the album whose mature, controlled sound rippled across culture.

Within months of the release of Blood Sugar Sex Magik, the Chili Peppers would be touring the US, with Nirvana and Pearl Jam in support, riding a seemingly unstoppable wave of popularity that would soon crash into a wall, when the pressures of the spotlight – and their growing global audience – saw Frusciante quit his favourite band in the world.

In the documentary’s final scene, a close-up shot captures Flea saying something remarkable. “As long as the longevity of the band stays together, and we keep it together as people and as musicians, we’ll always get better, and I think people will always like that,” he said. “As long as we stay together, and keep our love for one another and our love for the music, there’s no way that we’re going to fail.”

A lot has happened since he spoke those strangely prophetic words in 1991. Flea and Kiedis, the founding Peppers, are now both 60; Smith is a year older, while Frusciante is 52. (Josh Klinghoffer, by the way, has recently worked as a touring guitarist with two other US rock institutions in Pearl Jam and Jane’s Addiction. To his former bandmates, he holds no ill will: in a 2020 interview, he said, “It’s absolutely John’s place to be in that band. I’m happy for him, and that he’s back with them.”)

When Frusciante returned to the band, it relit a redoubtable creative spark. Last year, the group released two albums, Unlimited Love and Return of the Dream Canteen, which totalled 34 songs and 148 minutes, both produced by their old friend Rubin.

It is these new songs, plus the much-loved fan favourites spanning more than three decades, that the group is now bringing to Australia, for what will be Frusciante’s first performances on our shores since 2007.

“As I’m speaking to you, I can guarantee you that John is in his room playing guitar, trying to figure out different patterns to challenge his brain,” Kiedis tells Review. “Flea is doing the same, and Chad is probably planning six more tours with Iggy Pop, as we speak.”

“All of these boys love music so much that they can’t stop; they can’t help themselves,” he says.

“They must play and improve and explore, and that makes my job – my place in the band – constantly fun and interesting. I can’t wait to see where John has arrived in his guitar playing the next time we sit down (to write), and I have some greasy little poem on a napkin that I want to turn into a song.”

It has been a long, strange trip with no shortage of highs and lows, but finally, these four men are back together, in the place they love. Flea’s childhood suspicion was correct: he was going someplace good, after all.

Red Hot Chili Peppers tour begins in Brisbane (January 29), followed by Sydney (February 2 + 4), Melbourne (Feb 7 + 9) and Perth (Feb 12).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout