Producer Rick Rubin on music fandom, Paul McCartney and his book The Creative Act

After working with superstars from Adele and Metallica to Jay-Z and Johnny Cash, Rick Rubin has written a guidebook for turning sparks of inspiration into timeless artistic greatness.

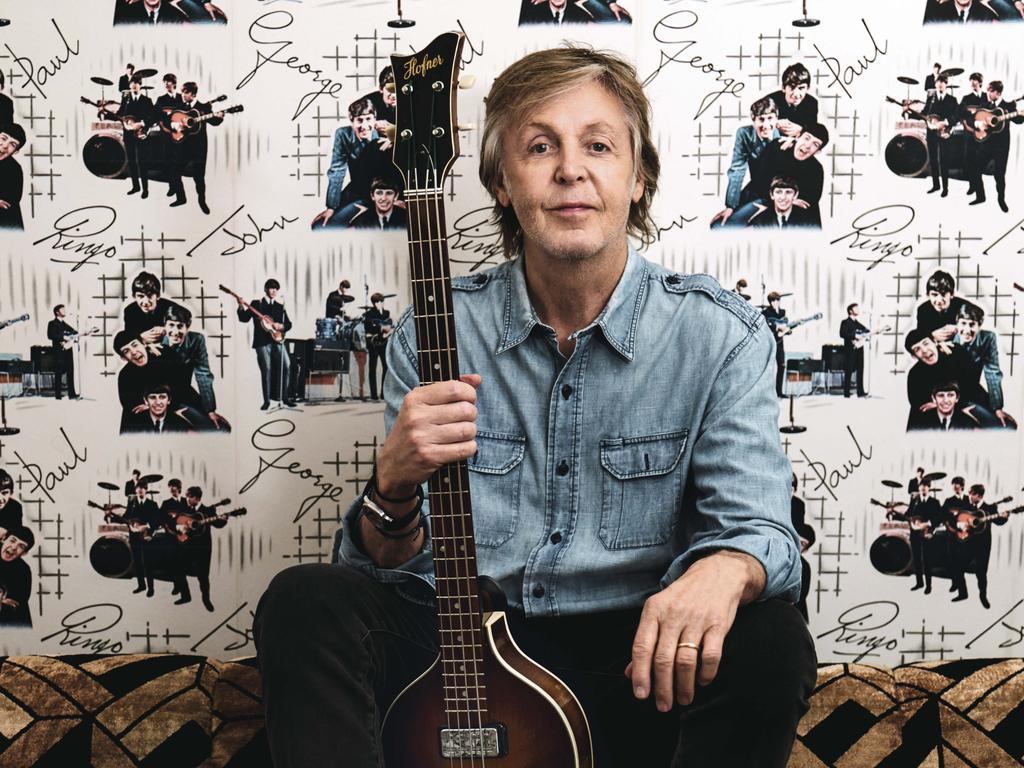

The world’s most recognisable pop musician was perched in a chair, leaning forward and balancing a left-handed acoustic guitar on his knee, a peerless songbook contained beneath his fingers.

At his feet, a man 20 years his junior sat cross-legged on the floor, the very model of an attentive student fiercely attuned to every word, note and melody being uttered by this singular teacher.

As a globally respected record producer, Rick Rubin had spent his entire adult life in service of coaxing, prising and teasing greatness out of the minds, bodies, throats and hands of some of the biggest-selling performing artists of all time.

Yet in this moment, sitting at the feet of a redoubtable musical master in Paul McCartney, time and space dissolved, and he was momentarily cast back to a childhood spent in Long Beach, New York, studying the world-changing art that this man had created with his friends from Liverpool.

Natural light poured in from a window beside the pair, while a single lamp was aimed at the instrument, which sprung to life in the hands of the Beatles great.

It just so happened that several cameras and microphones were trained on the two men, who were recording a TV series wherein the British singer-songwriter casually lifted the lid on his remarkable lifetime of creativity.

Rubin, meanwhile, arrived armed with a boundless sense of childlike curiosity and the rare gift of multi-track recordings from some of McCartney’s original studio sessions with his bandmates. Stood at a mixing board, the pair could easily adjust the sound levels to isolate and emphasise particular instruments or voices.

Filmed across two days comprising nine hours, then edited down to six half-hour episodes, the miniseries – titled McCartney 3,2,1 – had begun with an exchange between the pair.

“You up for listening to a bit of music?” Rubin asked.

“Yeah, what have you got?” replied McCartney.

“Here’s a little number,” said Rubin.

At the press of a button, the opening bars of All My Loving – a two-minute song by The Beatles released in 1963, Rubin’s birth year – burst from the speakers, triggering an avalanche of memories and stories from the man who wrote it, and who had not heard many of these isolated parts since they were recorded almost six decades prior.

“I’m glad it was filmed, because I wouldn’t have believed that it happened; I would have thought that I dreamt it,” Rubin tells Review. “I’m a lifelong Beatles fan. I love the music more than anything; they’re by far my favourite group. To hear Paul tell the stories of how things happened, and to be able to hear those (audio) stems that hadn’t left Abbey Road (Studios) before – it was just spinechilling. I couldn’t believe it.”

“At first, it was intimidating – but as soon as the music started playing, the music takes over,” Rubin says. “I could feel he loved it as much as I did; he’s a fan of it as much as I am. That’s the way it works: the people who make these things, we’re making it out of love. It’s all fandom: whether you’re in the audience, or whether you’re making it, you’re making this thing that you love – and then you get to share it.”

Released by Hulu in 2021 and now streaming on Disney Plus, the black-and-white series offered irresistible viewing for any music fan, as one man’s love for these timeless songs prompted the other to dart between mixing board, piano and acoustic guitar while illustrating how certain artistic decisions were made on the fly, then trapped in wax and shipped around the globe.

Which is how the cameras captured Rubin sitting cross-legged on the floor, looking up into that famous face and listening intently to a demonstration of the first song McCartney ever wrote at 14 – “a little guitar thing”, as he called it.

“That was an amazing moment, because nothing that you see was planned,” says Rubin. “He volunteered to play something, and because the guitar didn’t have a strap, he sat. I was standing, and it felt awkward, so I moved some stuff around and sat on the floor, because it just felt right for us to be closer. It felt like the student watching the teacher. It wasn’t intentional, but clearly, it’s what was meant to be, because it’s what happened.”

Rubin’s opening query to the 80-year-old Beatle – “You up for listening to a bit of music?” – was delivered with an earnest and ever-present sincerity that has become a hallmark, for his persona is one refreshingly absent any trace of irony, cynicism or sarcasm.

If McCartney were to turn the question around, though, the answer would be an unerring, emphatic yes, for Rubin – a superstar in the specialised world of record production – has always been up for it. In the course of his listening, he has helped shape the recording sessions for some of the most influential recordings of the past 40 years, across practically every popular genre, from hip-hop to heavy metal, pop to country, rock to folk.

“His aesthetic range is essentially limitless,” notes his snapshot biography – a line that may appear boastful at a glance, but is somehow more of an understatement when you consider the roll-call of artists he has worked with.

His production credits include Beastie Boys, Metallica, Adele, Jay-Z, Neil Diamond, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Lana Del Rey, Ed Sheeran, Johnny Cash, Kanye West, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Eminem, Linkin Park, Angus and Julia Stone, System of a Down, The Chicks (formerly known as Dixie Chicks), Justin Timberlake, LL Cool J, Neil Young and Crazy Horse, and Slayer.

Since he co-founded hip-hop label Def Jam Recordings in his New York University dorm room in 1984, Rubin has built a multifaceted and revered career in music, though much of it has centred on his role in the producer’s chair, nodding along silently, and occasionally chipping in new ideas or making suggestions to the performers.

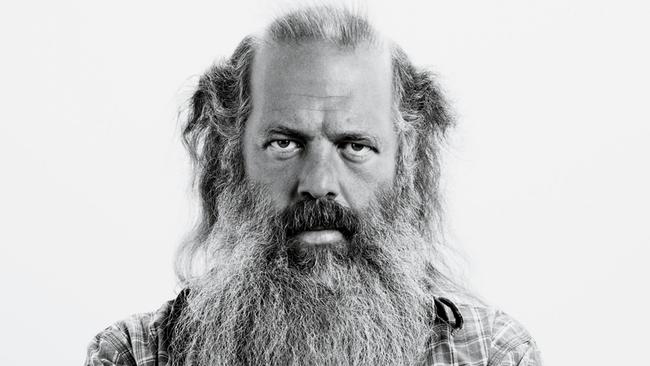

If he wasn’t sitting, it’s just as likely that Rubin – luxuriously bearded, and famously barefoot in all seasons – has been lying down somewhere comfortable, stretched out within earshot of the music being made, eyes closed, grooving along to the sound, ears wide open.

Widely considered an architect of modern hip-hop, Rubin realised that the recorded art form in the early 1980s bore little resemblance to how that music sounded in New York nightclubs, where DJs bumped beats and rhymes for tightly packed dancefloors.

His desire to close that sonic gap led to an undeniable wave that continues to crest even now. Although hip-hop is by far the most popular genre today, back then it was a countercultural reaction to mainstream music, and nobody who got involved thought it offered their road to success.

Famously, the nine-time Grammy Award-winner doesn’t read music and does not operate a recording console, instead relying on trusted engineers to twiddle the knobs – yet unusually in his line of work, neither of these deficiencies has affected his ability to influence art and those who make it. “Rick is a genius,” Canadian singer-songwriter Neil Young told The New Yorker recently. “You’re not gonna find a person who loves music more than Rick.”

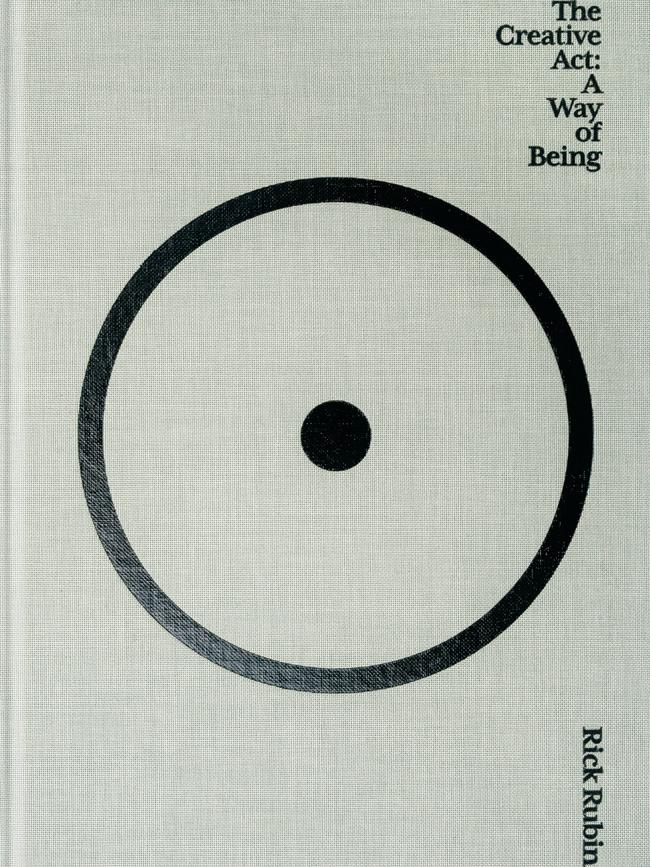

Though he has long resisted offers to write a book, that time has finally arrived for him at 59. Yet if the snapshot of high-profile artistic names mentioned above leads you to suppose he’s preparing to throw open the studio door and gossip about what it’s like to work with some of the most famous names in popular music, you’ll be sorely disappointed.

Instead, Rubin will soon publish a fascinating book titled The Creative Act: A Way of Being. Far from a memoir, it takes the surprising form of a guidebook for creativity. Packed with plenty of wisdom learned by working shoulder-to-shoulder with artists of all stripes, it is profoundly insightful, to the extent that practically every sentence on each of its 400 pages feels earned and honed for maximum impact.

Singling out snacks from this weighty meal of a tome is a hard task, especially as the tone and wisdom accumulates, such that the final quarter occasionally takes on the feel of Holy Scripture to creative types. Here’s an attempt, though.

In a book containing not chapters, but “areas of thought”, Rubin compares the process of finding artistic inspiration to collecting seeds, which “typically doesn’t involve a tremendous amount of effort. It’s more a receiving of a transmission. A noticing.”

“As if catching fish, we walk to the water, bait the hook, cast the line, and patiently wait,” he writes. “We cannot control the fish, only the presence of our line. The artist casts a line to the universe. We don’t get to choose when a noticing or inspiration comes. We can only be there to receive it. As with meditation, our engagement in the process is what allows the result. Collecting seeds is best approached with active awareness and boundless curiosity. It cannot be muscled, though perhaps it can be willed.”

Later, in an area of thought titled Great Expectations, the author notes that a creative act requires a series of steps into the unknown, with grit and determination, while accepting that the outcome is out of our control. “This destination may not be one we’ve chosen in advance. It will likely be more interesting,” he writes. “This isn’t a matter of blind belief in yourself. It’s a matter of experimental faith. You work not as an evangelist, expecting miracles, but as a scientist, testing and adjusting and testing again. Experimenting and building on the results. Faith is rewarded, perhaps even more than talent or ability. After all, how can we offer the art what it needs without blind trust? We are required to believe in something that doesn’t exist in order to allow it to come into being.”

Seven years in the making, this remarkable book is why Review connects with Rubin in early December on a video call from Costa Rica, where he has recently been recording on a mountaintop with US indie rock band The Strokes, and where he is working on the audiobook version of The Creative Act.

Wearing a grey T-shirt and white headphones sitting ajar atop his head, Rubin’s tanned face is quick to smile, and he immediately reveals a habit of holding intense and unbroken eye contact that becomes mesmeric at times. The image of a cobra swaying under the spell of a snake charmer comes to mind.

I mention this only because it’s highly unusual. The normal social compact with interviews, whether conducted in person or through a screen, is for the subject to look away while thinking and speaking, and only occasionally “checking in” by glancing back at the interviewer. Instead, Rubin’s blue eyes are locked on mine from practically our first moment together until we bid farewell 90 minutes later.

It’s a powerful choice to create warmth and intimacy between two strangers, and I’m left wondering just how much that non-verbal communication strategy has led to scores of artists – often flighty and insecure by nature – feeling deeply connected to him, and thus entrusting him. When I tell Rubin that I’ve been describing the book to friends and colleagues as a creative guidebook designed to help people think about making things, he replies, “Absolutely, that’s accurate. It talks about ways of looking at situations that allow creativity to happen. It’s a book that I wish I would have had when I was young.”

He worked with several writers over the years, including with American Book Award winner Verlyn Klinkenborg, yet earlier iterations weren’t quite living up to what Rubin pictured for the text. “The goal of writing the book was always for someone to read it, and want to stop reading to go make something,” he says.

That’s a lofty goal for any book, and by those standards, it might have never seen the light of day. After four years of experimentation, Rubin settled on working with Neil Strauss, a former music journalist for Rolling Stone and The New York Times who is better known for writing best-selling books including The Game (2005) and The Truth (2015), both deeply personal titles about sex, love, relationships and personal transformation.

“Eventually, Neil worked on one section, and it was the closest to the way I imagined the ideas being organised, where it made sense to me,” says Rubin. “And then we literally worked on the book together, sentence-by-sentence. Neil’s a journalist, and he writes like a journalist, and I didn’t want the book to feel like it had a journalistic take, because it’s not. It was like ‘unwriting’ the journalism in it, and making it more…”

He pauses. “I don’t know even how to describe what it is, but I think it turned out to be the way that it’s meant to be.”

Of course Rubin would say that; it’s the very sort of cosmic belief in fate – coupled with an unerring appetite for staying with the work, even when the path forward is hard, or appears unclear – in which he has invested his life, and inspired to produce in others.

But given what he writes in the book, about how all creativity requires a strong dose of blind trust, so that something new can pass into being, was he driven by that same core belief throughout its long gestation process, too?

“My trust was strong in it from the beginning,” he replies. “I spoke to many friends and writers, people who were much more experienced than me in this world, and when I described what I wanted the book to be, nearly all of them thought I was crazy: not only, ‘I don’t know how you’re going to do it,’ but, ‘Why would you want to write that book?’

“The general consensus was, ‘That’s not the book anybody wants from you. People want stories about the dorm room; people want your story.’”

Although that approach was undoubtedly the easier path to take, Rubin was uninterested in writing about himself, or even directly identifying any of the artists he’s worked with across the past 40 years, because the minute he inserted someone like Jay-Z into a story, he figured it would break the spell and rob the reader of the chance to imagine themselves in that creative situation, rather than a famous person.

With Strauss – who is Rubin’s longtime stand-up paddle-boarding buddy – they struck a tone that focused on the work, not the individual. “I don’t want a book about me; I want a book about the information that allows great things to be made,” he says simply.

If all this sounds like a surprisingly ego-free approach from someone who has worked with some of the biggest egos in popular music, that’s by design. Of course there’s a passage in the book on that subject, too.

“It is a disservice to the project to weigh our contribution to it,” Rubin writes. “Believing an idea is best because it’s oursis an error of inexperience. The ego demands personal authorship, inflating itself at the expense of the art. It can reject new methods that appear counterintuitive and protect familiar ones. The best results are found when we’re impartial and detached from our own strategies. We all benefit when the best idea is chosen, regardless of whether it’s ours or not.”

Even referring to The Creative Act as a “guide” or a “handbook” feels like imperfect language. Maybe it’s more like a map, or a lamp for artists to carry as they venture into the dark caverns of their creative impulses, while attempting to make things that fulfil their inner desires, and perhaps find an audience.

Although deeply serious in content, it hums with the playful, curious tone of an experienced mentor. This isn’t the school headmaster or religious figure delivering sermons from on high. It’s not prescriptive, it’s suggestive; Rubin freely states that doing the exact opposite of what’s written in its pages may work just as well, and if that inversion leads to great work? Wonderful.

“It’s not as simple as knowing how to play your instrument; it’s not as simple as learning how to paint,” he tells me. “It’s why the subtitle is A Way of Being: it’s a way of living in the world, where you’re experiencing the potential of art everywhere you look. Your breath gets taken away by the beauty around us all the time, in a way that might not for all people; in a way that probably does happen for children, because they’ve not seen it before.

“But we become used to everything we see; we’re jaded,” he says. “We’re used to seeing the things around us and taking them for granted. But we live in a world of wonder, and if we choose to see it that way, it’s very inspiring, and it allows us to tap into that flow.”

Children occasionally appear in its pages to illustrate ideas, particularly around the concept of “beginner’s mind”, which is “one of the most difficult states of being to dwell in for an artist”, he writes, “precisely because it involves letting go of what our experiences have taught us.” There’s a straightforward reason for this: Rubin recently became a father – his son Ra is five – as did Strauss a few years earlier. Both men have become attuned to observing how their children respond to a world filled with novelty, which is why some of those “dad mode” flames flicker throughout the text.

In Ra, Rubin says, “I do see the possibility for whatever’s happening, that moment is the most important thing. I see that in him, that he reacts in wild joy, or terrible pain, over whatever it is. He could jump in a swimming pool, and have so much fun, and be so engaged playing and splashing in the water, where the outside world doesn’t exist. It’s amazing how in it he is, and present. I love that, and I hope that it rubs off on me.”

Having previously spent much of his life in dark rooms with no windows, staying up all night and sleeping all day with blackout blinds, parenthood – a role he shares with his wife, the actor and model Mourielle Herrera – has shifted the longtime night owl’s routines considerably.

The man is familiar with transformation, having dropped 60kg about a decade ago, down from a peak weight of 145kg, by changing his diet and exercising with big-wave surfer Laird Hamilton. But being a dad has come with lifestyle trade-offs, too.

“I don’t go to see very many shows,” he says. “I used to go to loads of shows, all the time. Luckily I grew up at a time in New York when I was able to see everything from Talking Heads to The Ramones, AC/DC, David Bowie and Bad Brains. It was an amazing time to be there, to see all this ‘forever music’.”

He says this without a trace of lamentation or a sense that he feels he’s missing out on the other side of the musical equation, where the songs he produces are performed for live audiences.

Asked about the last concert that had lured him from the family home in Malibu, California, Rubin thinks for a while, then recalls it was a stadium gig by Red Hot Chili Peppers, the rock group with whom he has worked since 1991’s mega-selling Blood Sugar Sex Magik. “They’re amazing,” he says, beaming, having produced the two double-albums the quartet released last year, totalling 148 minutes of music. “I get to see them in the studio and it’s transcendent; live, it’s a whole other thing.”

But the family now travels as a pack, and since Ra was tired that night, Rubin only got to witness the first three songs of the Chili Peppers’ performance.

That small sampling was enough to sate him, though, just to feel the wild energy transference between band and crowd, so that he could carry that experience with him. And in any case, he says with a smile, he likes recorded music best.

The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin is published on Tuesday, January 17 2023 by Canongate.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout