Peter Garrett: solo album A Version of Now leads Midnight Oil comeback

Midnight Oil frontman and former federal politician Peter Garrett explains why now is the perfect time for a comeback.

No one has ever looked more relaxed and comfortable. Sitting on a sofa sipping tea, he is a formidable, familiar figure, happily taking stock of his life against the backdrop of a Sydney recording studio. In this chamber there is no opposition to shout him down, no policies on a knife edge, no Kevin Rudd. All that could cause a commotion here are the amplifiers, the microphones, the mixing desk and, of course, the man himself. Peter Garrett has come home.

Comebacks by 63-year-old musicians are rare, not least by ones who ditched their rock ’n’ roll career to enter federal politics, as Garrett did on the Labor ticket in 2004. That was two years after the singer said goodbye to the band that had occupied most of his adult life, Midnight Oil.

Now, in the space of just a few weeks, the singer has risen again, not once but twice, with the news that the Oils will tour internationally next year and that their frontman is about to release a solo album, A Version of Now, in July.

“No one is more surprised than me,” says Garett, more in the context of his solo outing than the Oils’ imminent return. Speculation on that has been rife since before he quit politics in 2013.

Today the singer is holding court in Hercules Studios in Sydney’s Surry Hills, a state-of-the-art recording facility owned by veteran producer and former Easybeat Harry Vanda. It was here several months ago that Garrett, aided by musicians including Oils guitarist Martin Rotsey, brought to life a batch of nine songs that germinated while he was writing his memoir, Big Blue Sky.

That autobiography, published and reviewed favourably late last year, was the conduit to the songs that make up A Version of Now. As with the book, the album, in its own way, documents salient points in the singer’s life, not least his transition from rock music to matters of state.

Garrett topped and tailed his memoir with lines from two of the songs on the album, Kangaroo Tail and I’d Do It Again. The latter, as he describes it, is an exit song, a commentary on his withdrawal from the political playing field.

“I saw the best of men and I saw the worst / I saw the best of women too, from governor to nurse / I straightened up and turned my cheek lonely in the night / You only get one chance at things to try and do what’s right.”

Garrett at the helm of the Oils trying to do the right thing during their 26-year tenure was a powerful political voice. Through songs such as Beds are Burning, US Forces and Blue Sky Mine, the Oils addressed the big issues of land rights, American military intervention overseas and the environment, among others, in a forceful, engaging and uncompromising way.

When Garrett made the leap to parliament and then to the frontbench, first as minister for environment protection, heritage and the arts (2007-10) and then as minister for school education, early childhood and youth (2010-13), some questioned whether he could be as effective in government as he was from the pulpit of the stage and recording studio. He’s cool with that.

“I went in there a sentient being with my eyes wide open,” he says. “I had strong connections to politics for many years in different guises and it was in some ways a natural step to take, if the opportunity came up, which it did. You lose some control over your own destiny when you do that. You surrender yourself to the vicissitudes of fate and events. That wasn’t the point. The point was I wanted to go and do it and I have absolutely no regrets about it.”

The first album under his own name has only vague traces of Garrett’s Oils output, aside from the distinctive gravel-and-dust, semi-spoken vocals. The singer co-wrote much of the material on the Oils’ 11 studio albums, but this is his first project where the bulk of the material is from his pen alone. Produced by the much-in-demand Burke Reid, whose many credits include albums by the Drones, Sarah Blasko and last year’s Courtney Barnett award-winning album debut, Sometimes I Sit and Think and Sometimes I Just Sit, A Version of Now tends towards sparse, melodic rock, coloured by Rotsey’s rich guitar stylings and a rhythm section of bassist Mark Wilson (Jet) and drummer Peter Luscombe. Also making appearances are the Jezabels’ Heather Shannon, Bluebottle Kiss’s Jamie Hutchings and Garrett’s three daughters, Emily, Grace and May.

The idea of making a solo record never occurred to him before, says Garrett. There was never enough time. “My take on it is,” he says, “because I’ve been busy, because I’ve been focused on politics, because I’d done a bunch of other things and had a career in a rock band that went at it pretty hard, I’d never really had the situation where there was a lot of space — in my head, enough space in the day for other things that you can tend to, to water them.”

As his memoir unfolded, however, songwriting space emerged. “I had written a few little things I’d been playing around with over time that I thought might fit in the book,” he says. “Then I thought I might have more than that. It was free-range poetry. Then as I was finishing chapters or editing, in the afternoon … there was an old guitar in the corner of the room saying ‘C’mon, pick me up’, which is what I ended up doing, just fiddling around. And then they came together as songs.”

The seeds of the solo project began to blossom fully when Garrett, Rotsey and didgeridoo player Charlie McMahon embarked on a road trip across the western desert last year.

“I’d gone there on a bit of a check-see on some of the things I’d been involved with when I was in government,” says Garrett. “I wanted to see some of the things that were still going, just as a citizen. Martin had brought his guitar and at night we’d just sit around playing music.

“I said I had a song or two. That was a surprise out of the sky and he said I’d better play them. So I did. Then I thought I might as well record them. Then they kept on coming. It was more by accident as by anything else. I thought there was the possibility that the Oils might reconvene at some stage, if we could get everybody together, but I didn’t expect this to happen at all. Once songs have a bit of a life you have to keep going with them.”

Other songs on the album focus on his family life (No Placebo, Only One, Homecoming), his return to the rock business (Tall Trees) and an all-encompassing foray into rap, the closing ItStill Matters. Clearly rock ’n’ roll still matters to Garett. He makes that very clear on Tall Trees, the opening song.

“I’m rolling back, like a monk that’s taken holy vows / I’ve jumped aboard the here and now I’m back / Like a Boeing safely landed, a vessel that’s been stranded, I’m back.”

Garrett looks well on his 63 years, aided, perhaps, by an instantly recognisable head that has changed little since he was treading the boards in the pubs of Sydney’s northern beaches with the Oils in the 1970s. What could account also for his ageless demeanour is that his stress levels have decreased since leaving parliament, not that he had any foreboding about entering that turbulent domain or about any of his actions while there.

“It’s not to say it isn’t a frustrating job,” he says, “but I didn’t feel the frustration of not being able to open up on any sundry topic whenever I felt like it. I’m a student of politics. I’m a supporter and a believer in our system. I wanted to deliver good things for people, but I understood the importance of the disciplines of politics, the importance that you do join the team, that you are essentially there to work with other people to try and put policies in place that you think are going to make a difference.

“It says something about the political junkie that I have always been that the idea of being in the House of Representatives and seeing legislation through gives me just as much of a thrill as watching AC/DC blow the roof off the Entertainment Centre.” If not quite a highway to hell, Garrett’s political path was littered with obstacles during his ministerial terms, particularly the first, under Rudd, when he was demoted by the prime minister over the botched home insulation program in 2010. Garrett’s exit from politics followed his backing of Julia Gillard against Rudd in the 2013 Labor leadership spill. He is particularly proud of what he achieved under Gillard, including his involvement in the National Disability Insurance Scheme Bill and the Gonski education reforms.

“That’s not to say it was a magic carpet ride,” he says of his nine-year stint in Canberra. “Sometimes you were in the valley of death, fighting off the Valkyries. It’s a place where your human frailties are clearly exposed; as, hopefully, are your strengths. For me, it wasn’t that it wasn’t how I expected it to be. I know many people in modern democracies are frustrated with the capacity of their elected governments to respond to change in the issues that they think are important. It’s an imperfect system, but it’s the best one that has been devised so far and from my perspective it was a genuine and real privilege to be a part of it.”

He describes politics as “the messy, slightly ugly business of getting things done without shooting other people. That’s what it is and that’s why Australia is considered such a great place to live. I don’t see the political part of my life as a stage on which I had to take a leading role. I saw it as being another kind of vessel altogether on which I was a crew member.”

Garrett got his first taste of singing and of politics while studying the latter at the Australian National University in Canberra in the early 1970s. It’s a little amusing, including to him, that such a powerful Australian voice — literally and culturally — should cut his teeth on the classic rock songbook, channelling Deep Purple, the Doors and Free to small gatherings in Canberra pubs in his first band, Rock Island.

“The only reason we got anywhere is that we were able to get from the top to the bottom of Smoke on the Water without stopping,” he says. “Probably anyone can.”

What he did learn from that experience was how to work an audience (“getting songs to land in the right place”), and his fortunes improved from there. He describes his audition in 1973 for Midnight Oil, who were called Farm at the time, as a thunderclap moment. That set in motion one of the most successful careers of any Australian rock band of their era. Now it looks likely that there will be many more bursts of thunder as the Oils crew — Garrett, Rotsey, guitarist Jim Moginie, drummer Rob Hirst and bassist Bones Hillman — returns to the spotlight next year.

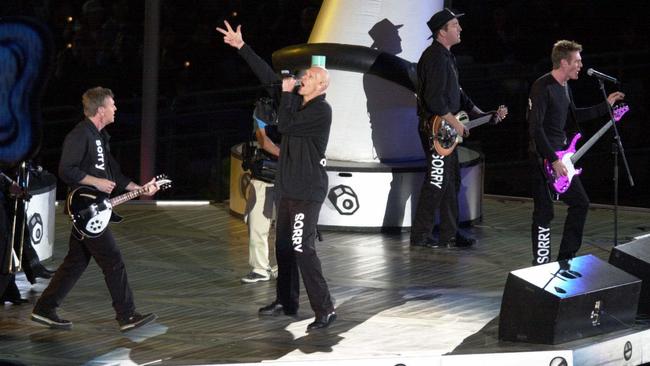

Garrett is playing down, or playing dumb on, just what form the next incarnation of Midnight Oil will be, but it seems certain that it will be on a grand scale. Aside from a few appearances in the noughties, including their memorable Sorry slot at the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000 and at the Wave Aid (2005) and Sound Relief (2009) charity events, it will be Midnight Oil’s first run of shows since the 90s. The singer acknowledges that the reunion has been discussed, but says no details have been finalised.

“We had started to chat,” he says. “The others had sent a few clues out that they were around. I’m around, so I’m up for getting together with people. People have other lives too, other careers. It was a question of whether we would get everybody in the same room for a while. If everybody is still enjoying playing and can get together, and do that thing that tied us together as Midnight Oil, then there is no reason why we can’t think about doing it in the future. We don’t know what it will be. There have been discussions about touring and recording, but nothing has been finalised. I know everybody is keen for it to be creative,” Garrett says, “if it can be, but it’s very early days.”

Nevertheless, it’s a no-brainer that the Oils’ comeback will be huge. That means an extensive tour here and overseas, most likely with a new album and a marketing campaign around their back catalogue attached. No band of this stature announces its re-formation as much as a year before it happens without there being some significant strategy behind it.

Garrett has set aside all of next year to be with his bandmates if necessary. That has to amount to more than a handful of trips down memory lane. One need only look at Cold Chisel’s 21st-century renaissance to see what is possible for an iconic Australian rock band of a certain age. Coincidentally, Chisel’s recent success has been under the management of John Watson (and partner John O’Donnell), who worked at Sony, Midnight Oil’s label, during the 90s. Garrett understands the Chisel comparison. Age is no barrier to success in the rock world if it is plotted properly.

“I love the fact that Chisel came back and made records,” he says. “And they are good records. One of the things I wrote about in the book was going and hearing Muddy Waters, just as a student when I was starting to get interested in bands. I’m not sure how old he was, but he was older than me; so were his band. You were in the presence of someone who lived, breathed, ate it and turned it into something they could share. It’s still about whether at any age the hairs on the back of your neck stand up when you play together. If you can do that you should play for as long as you can stand up.”

In the meantime Garrett is looking forward to standing up by himself, or at least under his own name, for a series of gigs to promote his album. And he’s glad to be back doing what he did for 30 years, singing songs for a living..

“In many ways I couldn’t be happier,” he says, “even if I’m surprised by it. I have few expectations about what it may or may not mean or do. I’m just being very aware that you don’t get many rooms to occupy in your life and I’m occupying a room that is kind of new, but I’m very familiar with at the same time.”

A Version of Now is released through Sony Music on July 15. Details of Peter Garrett’s Australian tour will be announced on Monday on petergarrett.com.au.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout