The inside story of Midnight Oil’s Sydney Olympic Games protest

On the 20th anniversary of the Sydney Closing Ceremony, four founding members of Midnight Oil recount what happened on that night.

At the closing ceremony of the Sydney Olympic Games on October 1, 2000, Sydney rock band Midnight Oil used the global platform offered by an estimated television audience of about one billion people to make the biggest political statement of its career.

In a moment that was kept secret from all but a handful of people, just before the musicians stepped on stage at Stadium Australia to perform their signature song Beds Are Burning, they removed black coveralls to reveal a hidden layer of black overalls that prominently displayed the word “sorry”, as a nod to the national apology that the band believed was owed to Indigenous Australians.

Sorry was the word that the prime minister of the day, John Howard, refused to say to First Nations people for what had occurred since white settlement, including the Stolen Generations, despite a popular groundswell of support for reconciliation that had seen about 250,000 people march across Sydney Harbour Bridge in May 2000.

On the 20th anniversary of the greatest moment of protest in Australian music history — and ahead of the band’s upcoming collection of collaborations with Indigenous Australian musicians named The Makarrata Project, which foregrounds a political document known as the Uluru Statement from the Heart — the four founding members of Midnight Oil recount here the lead-up to that night in Sydney and its aftermath.

(To watch the performance on YouTube, click here; the video is unable to be embedded in this article.)

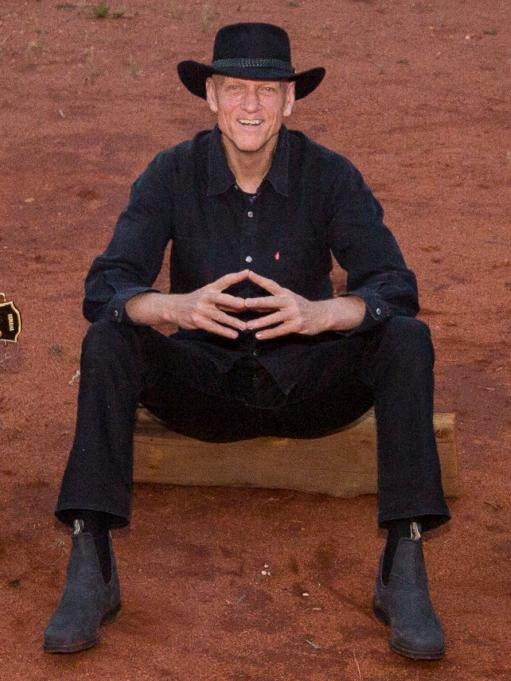

Peter Garrett (singer)

In your 2015 memoir Big Blue Sky, you wrote about the band camping on the side of a stony hill near the Indigenous community of Papunya, Northern Territory, looking out across the purple MacDonnell Ranges, sitting around a campfire and talking about how best to approach the Olympic Games closing ceremony performance. Thinking of the night itself, though, what sticks out in your mind?

A couple of things. The first would be the moment, that sort of half-second collective gasp of breath from everybody in the stadium when they realised what was going on. It wasn’t ‘til the cameras came in close, onto the actual overalls with the “sorry” inscription, that people tweaked to what was happening. And then in very quick succession, you had a big roar from the crowd, and then literally thousands of people — including athletes from other countries — running towards the stage, to be a part of that moment.

And I think just the sense of everybody being on their feet — and at the same time, people in their living rooms or in clubs and pubs, or wherever they were watching it, being a part of that moment as well, which was so long overdue. And eventually, our subsequent prime minister — prime minister [Kevin] Rudd — was the one who tendered the formal apology in the parliament. And of course, I was in the parliament for that, in a different role [as a government minister].

But I think also, the Games themselves; in one way you look at the Olympic Games and all you see is the world’s biggest sporting event, and that’s the beginning and end of it. The discussion is always: how bright can the fireworks be? How good’s the dancing, or what’s the angle that Sydney is bringing to bear?

And in 2000, Australia essentially showed its oldest culture, but still, a vital culture — the First Australians — as being the linchpin of what we were saying to the world. So you had the women who danced at the top of it [the ceremony], and the fact that Cathy [Freeman] won the 400 [metres final], you had Yothu Yindi playing; you had quite a strong sense that this wasn’t just another Western country putting on an event where they managed to get the stadium built in time. It was something else, deeper and stronger, which resonated more.

But it was a journey unfolding, and it was one to which was attached a lot of heartache and sorrow for First Nations people. And we could be really good at putting on the Olympics, and the buses all ran on time — but essentially, we still needed to fix this historical wrong and take the stain off the conscience of the nation.

Where does that performance sit among everything the band has achieved?

Well, I think that was obviously an important thing for us to do. The fact was that [John] Howard didn’t want to say sorry. As prime minister, he was utterly stubborn about that fact. So to be able to jump up at that moment and make the call is something which stands out for me as an important opportunity for us to have been able to grab by the tail and run with. You’ve just got to do those things when they come along, if you get the chance.

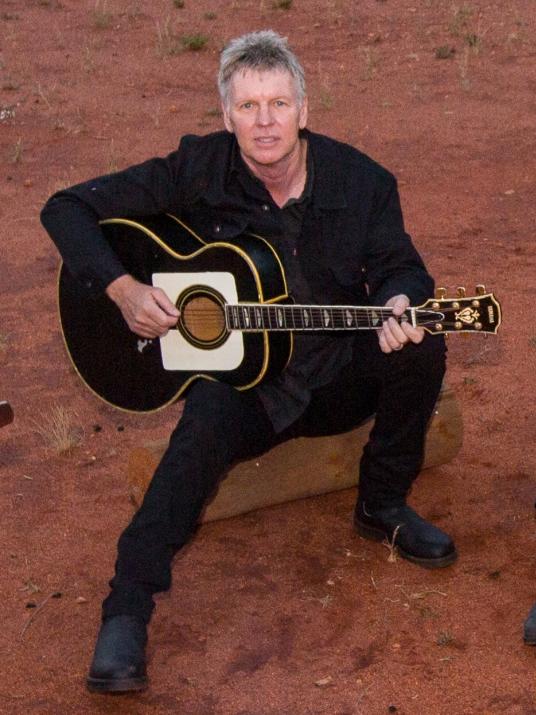

Jim Moginie (guitarist/keyboardist/songwriter)

What do you recall of how the “sorry” suits decision came together?

We were asked to do it, and we didn’t quite know what we were going to do. I think we were going to do a single or something ridiculous, which was The Real Thing [a live album released in July 2000, whose title track was a cover of the 1969 Russell Morris single]; I don’t know how that would have worked. When we were out there in that landscape [near Papunya], with our history out there, we went out there and we all camped, including Gary [Morris], our previous manager. We were just sitting under the stars, around a campfire, and talking about whatever we were talking about. And I think at some point, he [Gary] just said, “Look, you’ve got to do the song. It is the song that spread the message worldwide at the time” — which was Beds Are Burning, of course.

I mean, talk about a song that we never would have expected; you don’t know that something’s anthemic before it becomes anthemic, do you? I don’t think we were that self-aware. It did certainly sound a bit anthemic when it was mixed; that was the word I used to Rob when I came away from the mix that day. We were playing at the Blacktown Workers Club and he said, “How does the mix sound?” And I said, “It sounds anthemic.” I’d never said that about any of our songs before.

I think there’s something about being in that place [near Papunya], and what the message we were taking to the world with the Olympics was. And plus, John Howard was totally out of touch with what the real tenor of the nation was. “Oh, well, it doesn’t matter what anyone thinks about walking across the bridge — I’m not going to change my mind about this. So what if 300,000 people are walking over the [Sydney Harbour] Bridge? It’s not going to change my mind one bit.” Guess what, mate? Up yours. That’s what the whole Olympic thing was.

It waxes and wanes, but at that time certainly, people were really thinking about it. Whether we were part of that conversation… I mean, the whole thing with Charlie Perkins, and then you think about when Indigenous Australians got the vote, and then you think about the various artists like when Christine Anu came along, and all the great Aboriginal art movements of the 70s — which came out of Papunya, of course — and the dot paintings, which gained international recognition for Aboriginal people. And then Beds [Are Burning] and other things, just raising the awareness of the whole issue. It just seemed to be coming to a head then, and I think they were trying to stop any sort of protesting in the streets, so that the overseas cameras wouldn’t see what was really going on here.

Things have changed, obviously; there was Kevin Rudd’s apology. Some things have changed a lot and some things haven’t, but I think at least with the Makarrata [Project] we’re just continuing the fight, really. The same things keep happening in history; there’s misinformation, and the Aboriginal world is a world that perhaps we don’t understand that well because it’s connected to spirit and country, and once you start talking about those sorts of terms, a lot of peoples’ eyes gloss over and they say, “You know what? I want to watch the footy.” I think that’s the ability for people to keep forgetting what they already know. I think if Midnight Oil’s a thorn in the side of people, so be it. Great; let it be that.

Anyway, Pete’s recollections are right. That’s where [we decided], “This is the song that needs to be sung at the Olympics”, and not our latest single, or some paean to whatever. It was a good moment.

In those weeks leading up to that moment, when you were all carrying that secret — and Gary, and maybe a few others — what were you hoping it would achieve?

We had done protest gigs before; we’d done Exxon [in Midtown Manhattan in 1989], we’d done the Clayoquot [Sound] protest, where the loggers on Vancouver Island [in Canada] nearly rolled the car and tried to kill us, almost [in 1993]. We’d been in situations where it had been edgy and kind of dangerous. But this was the Olympics ceremony, so what could possibly go wrong, apart from the threat of being sued for disrupting the broadcast or doing some sort of protest that was out of whack? We certainly didn’t want to do that, but a point needed to be made.

I think we asked Mandawuy [Yunupingu] from Yothu Yindi what he thought and he said, “Yeah, go for it — do it”, because they were playing as well. And we got some approvals from people: “What do you think? Is it inappropriate to do this?” And they said, “Oh no — it’s the f..kin’ Oils, mate. Do it.”

So the only thing that could have happened would be that we would have been sued by the [International] Olympic Committee for loss of revenue if they’d had to pull the plug on the broadcast. But I mean, “sorry” on a suit? Big deal; everyone’s saying it anyway. Midnight Oil was just saying what people were saying on the street. But because we were all singing that song and wearing that word, of course it combined into a whole other thing. But the impression that I got when I heard people talking about it the next day was, “We were just dancing to it; we were celebrating being Australian”.

Because that’s part of what it is, isn’t it? There’s a lot of contradictions and ironies about Australia. We can dance to a song about Aboriginal people and be a racist. That’s the whole contradiction of music and politics. But that song? I’m glad we did it, and it made the point. We got in, we got out, and we survived. It was happening in our country like apartheid; we just needed to shine a light on it.

Our prime minister certainly wasn’t doing anything about it, and wasn’t going to do anything about it. So guess what? We had to take the law into our own hands and go to the world, and bypass Canberra, and all the political processes. Some people would have said, “Sorry — what’s that? Is that a clothing line?” But just having a conversation, that’s what the whole Midnight Oil thing’s all about.

When you know it’s right, and you know you’re being a bit of a pain in the arse… but also, it needs to be said. So what are you doing to do? Just sit on your hands and say nothing? Nup — that’s not the Midnight Oil way.

Martin Rotsey (guitarist)

What are your recollections of those campfire discussions near Papunya, and how the band came to a consensus on what the Olympics performance would look like?

Look, I think we’re still trying to work out what happened in that discussion. I don’t know whether anyone has given you a clear idea. We were there, and our manager Gary Morris was there as well. We knew if we were going to do the Olympics, we wanted to do something, and we didn’t want to do perhaps one of the better-known songs that we already had out there.

The sorry campaign [for reconciliation] was obviously up and running. I can’t remember exactly what happened around that campfire. There was perhaps talk of doing the Easybeats song Sorry — to just break into that. And then we talked about putting T-shirts on, with the word “sorry” — and then the discussion was, if we’re going to do it, how can we maximise the impact? We didn’t know whether we would be able to get away with doing it.

Do you recall who made the custom “sorry” overalls? Who actually did that handiwork?

Well, I was there. I can’t remember the name of the person. They were in Taylor Square in Sydney, and we went up there. Gary had got some ideas about it, but I think we went up there and the first run might have been a lot of small “sorry” [words] all over the suit. But I didn’t think that that would come out clearly enough on the TV screen, so we ended up just doing less “sorrys”, but they were really big, so that wherever they pointed the camera… we made sure there was one on the front of Pete, on the side of Pete; they were very strategically placed so that they really couldn’t film the band without getting the word. [laughs]

Were you the only band member who was in those design discussions?

Well, a lot of people were out of Sydney at that stage. And it wasn’t definite that we were going to even do it, because we had to wait… We had meetings. I remember going along to meetings with some of the people from the Olympics, and they were quite legalistic about hijacking; “brand hijacking” or something. I can’t remember the exact terminology. But yeah, it was pretty serious.

So at the end of the day, I think they realised we were going to do something, but they were afraid to ask. [laughs] I think we just thought, “Look, if you’re going to have Midnight Oil — that’s what we do. It’s all part and parcel. Of course we’re going to do something.”

We had a rehearsal, where we’d made black overalls. We did the stage rehearsal out at [western Sydney suburb] Schofields during the day, and we just had our black overalls on. They did all their camera angles and that was all fine; they were happy with that.

The night of the performance… we had two other people on stage with us. We had Glad Reed and Kathy Wemyss playing brass with us. So we were all in one of the big change rooms out at Homebush, and we had our secret “sorry” suits on underneath, and the black overalls on top that we’d worn to the rehearsal. They kept checking us; they’d come in and they’d see what we were wearing. We were looking just like the rehearsal.

It was a huge event; one of the most tightly scripted things we’ve ever done. We were taken into one of those long corridors that leads into the stadium, and there’s security people around; a lot of people with microphones and headphones on, telling you, “You’re going to be on in one minute; in 50 seconds…”

And at the very last moment when we’d actually been announced, and we were walking out onto the stage, we pulled off the plain black overalls. I remember there was a security guard beside us, sort of looking, and he just gave us the thumbs up. [laughs]

But I guess we didn’t really know whether we’d get away with it, even then. We thought, “They’re just going to turn the cameras off…” But we started the song, and you just looked out and you could see the audience — they got it. There was this wave of support. It was a magical moment, and I had friends out in the audience who were telling me they got great pleasure when the camera panned across to John Howard’s face. It was a commando event, really.

I know the band has its collective ideals and values, but what did that statement mean to you, personally?

I just couldn’t understand why we weren’t… we’d had the reconciliation bridge march at that stage. It just felt like something that we all needed to do. And look, it took a long time to do after that, too; it was 2008 before the apology. But it felt like you just had to stand up and be counted for that movement. It was very important to be part of that.

Other than Gary and Arlene [Brookes] from your office, how many other people knew the secret of what would happen, ahead of the night itself?

And the designer of the clothes. We had a tour manager, Craig Allen, that works with us sometimes. He knew because he lived out near Schofields, so we were around at his parents’ place when these bags of clothes arrived. We opened them up, and that was the first time we’d really seen them all printed, and we put them on in secret. Very, very few people; certainly nobody from the Olympic side of things knew what was going to go on, at all.

What was it like for you to carry that secret?

Look, there was a bit of trepidation. There was this euphoria sweeping Sydney at the time. And I’d been to a lot of the Olympic events, just as a spectator, like a lot of people in Sydney. I guess there was a feeling that it was a big party, and especially because we’d had those meetings with some of the people from the Olympics, there was a bit of pressure on not to do anything; “don’t spoil the party.”

But I think it just had to be done. You toss these things up, but I think it just felt right to do it. I think once we’d decided to go ahead with it, we just hoped it worked. We hoped it got the message across, and the cameras picked it all up.

Pete’s vocals were live, but for the rest of you — including the brass players — is it true that you were miming?

Yes, it is true. That wouldn’t be our preference, to do it that way; but definitely a live vocal. In that format, there wasn’t any time. The change over between people before us and people after… it’s a big stage show.

It was never even talked about, that that was a possibility. So we could have held our high ground and said, “We’re not playing, because we’re miming.” But again, on balance, we thought, “Yep, this is worth doing. At least we’ll have a live vocal, and we’ll get what we want out of it. We’ll get the message across.”

On the actual broadcast, you were only on stage and screen for about four minutes. What happened immediately afterwards?

Well, we were taken back to our little room. Look, I can’t remember, to be honest. It’s a bit of a blur what happened immediately after, because we still had to go back on; there was a sort of final parade around. So there was a bit of waiting time. We had our friends and family there, and they were coming back, telling us how it had gone, and how it was filmed.

Looking back at it now, 20 years after the fact, how does it make you feel to reflect on how it all came together?

It seems like it was absolutely the right thing to do, now. As I said before, it took a long time for the apology to happen. There was still a lot of resistance, politically, to it. Eventually, 2008 was the apology. It was the right thing to do; it’s just frustrating how long it took. We are proud of it, of course. But the real payback for it is when change actually happens. It took a while, and it’s still going on.

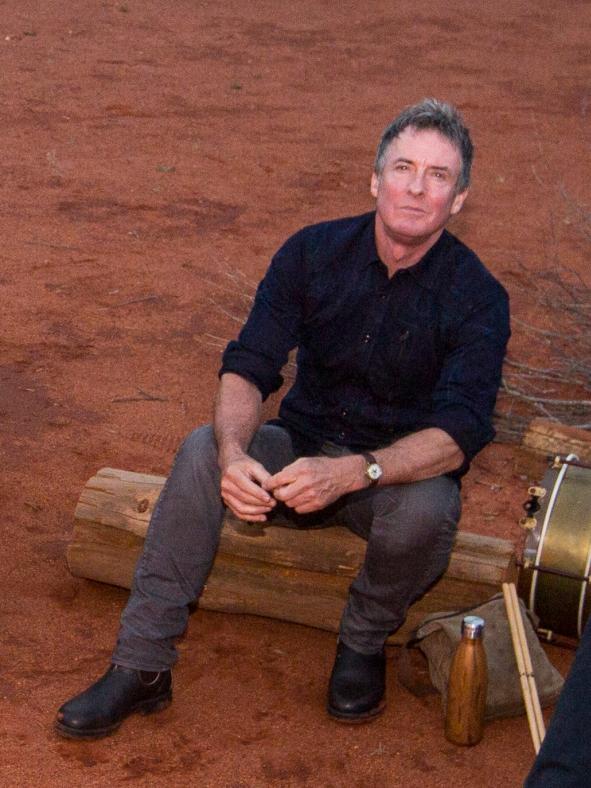

Rob Hirst (drummer/songwriter)

Can you talk me through your memories of camping out at Papunya, and then step towards the night itself?

We sometimes went to the desert when we wanted to make some big decisions. Maybe there’s a clarity of thought out there, and we can all see the big picture a bit better. We did camp in a little valley outside Papunya for a few days. The band was very divided about whether to be involved with the Sydney Olympics. I was in the “pro” camp from the beginning, because I’d been working with these athletes [on an album project] and I’d found them mostly to be incredible people.

Everyone was just so enthusiastic, and I don’t know if you remember, but there was also a lot of anti, negative sentiment around before it, as there is with all Games. I mean, history is written; there was that thing about “Who put Prozac in the water?” It was just the most incredible time to be in Sydney. We all went to lots of events; we saw Cathy [Freeman win], and it was perhaps the last time — particularly now, from a COVID view — that Sydney was completely unified and joyful and proud. We didn’t know it at the time.

I think it took a while to come to a decision that we’d do it, but we found out Yothu Yindi was going to appear after us, and we knew that Christine [Anu] was going to sing My Island Home, a Neil Murray song. We didn’t know at that time that Darren [Hayes] from Savage Garden was going to wear his Koori flag T-shirt. But we realised that we could be part of something, and of course, Howard hadn’t said “sorry” at this stage, and we thought, “This is the opportunity.”

But I’ve got to say, even five minutes before we walked down to that massive stadium, we were still debating whether it was a good idea. We had coveralls over our overalls; only artistic director David Atkins knew that we were going to pull this stunt. He told us, “I didn’t have this conversation with you. You do what you’re going to do.”

But even looking down the long corridor into a stadium of more than 100,000 people and an international audience, right up until the time we heard the roar go up when the cameras actually picked up the word “sorry” and there was this massive… it was like a primordial roar went up. It shook the ground, and we knew that the gesture we were making was going to be well-received. Not universally; there was always going to be the shock jocks and others, and naysayers.

There was an avalanche of support because that’s what people had been thinking for a long time. And it was worth it just to see John Howard’s face on the big screen, with that rictus grin that he used to hold when he knew things had gone horribly wrong.

Was it as simple as that? Was the driving force from the band’s perspective purely to stick it to the leader of the day for his refusal to apologise?

Well, Howard was the main obstacle. He was refusing to go in that direction. We’d walked across the bridge, amongst hundreds of thousands of like-minded people, here and around the country. A bit like this terrible hold-up with the Uluru Statement [from the Heart], there was a terrible frustration, and we thought, “Well, we need to be part of the circuit breakers. Alone we can’t make this happen, but there’s a lot of people who want it to happen”.

And then of course, Rudd came in and made it happen quite soon after he got in. But it just seemed like, if not us, then who? Would we get as huge an opportunity again? Probably not. So let’s do it.

There were some funny moments; my late mother saw it, and I went over [to see her] the next day. I said, “Oh, did you see us on the TV?” She said, “Oh yes, Bob”, as she used to call me. “There was one thing I didn’t like — I didn’t like that you had the word ‘Sony’ written on all your jackets”. [laughs] She was always very anti-commercial, my mum.

But the most interesting thing? The Oils have always had a very big and very analytical French audience. They love their politics over there, including Australian domestic politics. I remember Pete and I were rushed into another room as soon as we finished the international telecast, and with a link-up we were introduced to Canal+ or one of the big TV networks in France. And they were already intently discussing the ramifications of what it meant for Indigenous Australians, and the history of the whole “sorry” issue.

It was just extraordinary. Typically, it was actually more thoughtfully and better articulated by the French than anyone ever did here. And that was one of the great joys of touring Europe — all of those countries, particularly northern Europe, were always fascinated by the combination of music and politics, and wanted to talk about it at length. More than here; more than almost anywhere.

Looking back now, on the 20th anniversary, where does that four-minute period in the band’s career rank among your pride in everything that Midnight Oil has ever achieved?

Oh, f..k. I don’t know the answer to that question, Andrew. But I guess I’d relate it to our current project: maybe there’ll be some moment — hopefully sooner rather than later — that we can be involved in a similar grand gesture here, in order to get this marvellous document, written by so many great Indigenous authors around this country, this Uluru statement… Obviously people are distracted by the dreaded plague this year, but that will go, and then other massive, pressing issues — like justice and reconciliation for our First Nations people, and climate change — all of these will come back, and already have, with Black Lives Matter this year.

I can’t put any particular weight on that moment; it was kind of like a culmination of a lot of things that we’d done for decades before. But it would be nice to think that, before we hang up our sticks and picks, that we can push this whole Statement From the Heart a lot further down the track than it is now, because the majority of people of all backgrounds, colours, races in this country want it, and they want it in the constitution. At the moment, that’s off the agenda, and we’ve got to put it firmly back on the agenda.

Is that your chief hope for the release of The Makarrata Project, perhaps when compared to other Midnight Oil releases? Is the hope and intent for these songs a bit different to anything else you’ve put out before?

Well, if what we’re doing can combine with all the other myriad things that other folks are doing around and towards the same goal, then collectively, we can move it front and centre again. After 232 years [since colonisation in 1788], we can actually move to a place that we should have a long time ago.

We’ll be very happy to do our bit on this, and the strength of the album certainly comes from combinations of people, and it will be combinations of folks in this country that will actually make the difference and get this unfinished business done, for good and all.

The Makarrata Project will be released on October 30 via Sony Music, with all profits from its release to be donated to organisations which promote reconciliation and raise awareness of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout