When Taylor Swift was 13, she was a walking, singing question mark. The budding musician was merely one contender among the masses; an unknown quantity who might just amount to something.

Nothing is a certainty in the music business, where shifting cultural trends and audience tastes can see hot performers turn icy cold in the space of a season.

Most never achieve a career that reaches lukewarm; some get spat out of the machine so fast and far that what remains is the equivalent of reheated leftovers.

The performing arts are a brutal business, and the only thing individuals can reliably control is how hard they’re willing to work on their craft. The rest? It’s not up to them.

For Swift, the early signs were promising: 13 was the age she was signed to a development deal with RCA Records. That was only a year after she’d written her first song, titled Lucky You.

Perhaps fittingly for an untested naif, it was the sort of offer that a record label executive makes when they hear something promising in the work of an emerging artist, but they’re not quite ready yet to roll out the red carpet for a full-fledged record deal.

Still, it was better than nothing, and her efforts had not been in vain. By that point in 2003, Swift had shown no small amount of pluck in her attempt to realise her dream of a life in music.

Her first visit to Nashville, the home of American country music, had taken place two years earlier. Her parents drove her up and down the city’s famed Music Row, while she shopped demo CDs of herself singing along to karaoke music.

At the office of each record label, she hopped out of the rental car, walked in and pitched herself to a series of receptionists. “Hi, I’m Taylor,” she told them, handing over the wares and hoping the disc made it further than the front desk. “I’m 11. I really want a record deal.”

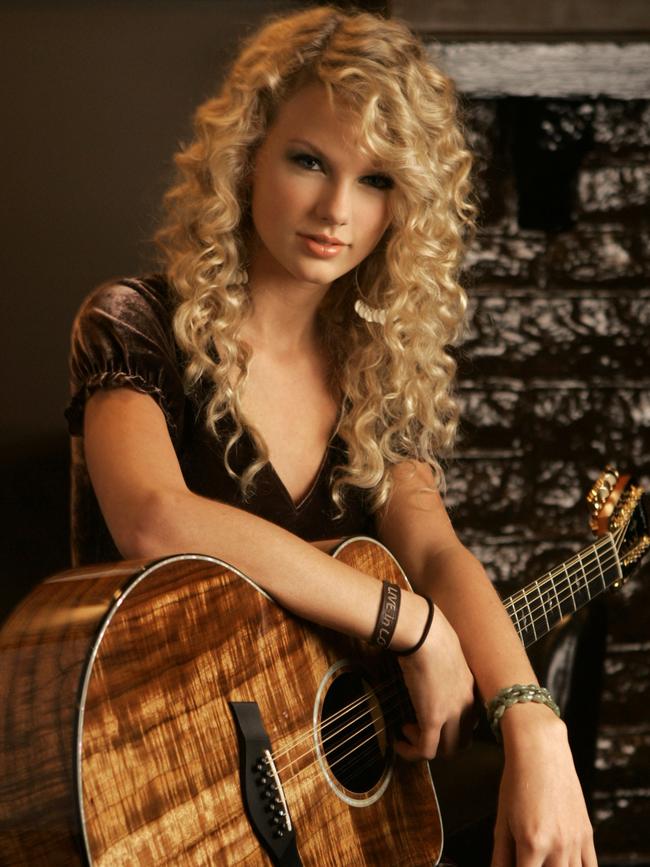

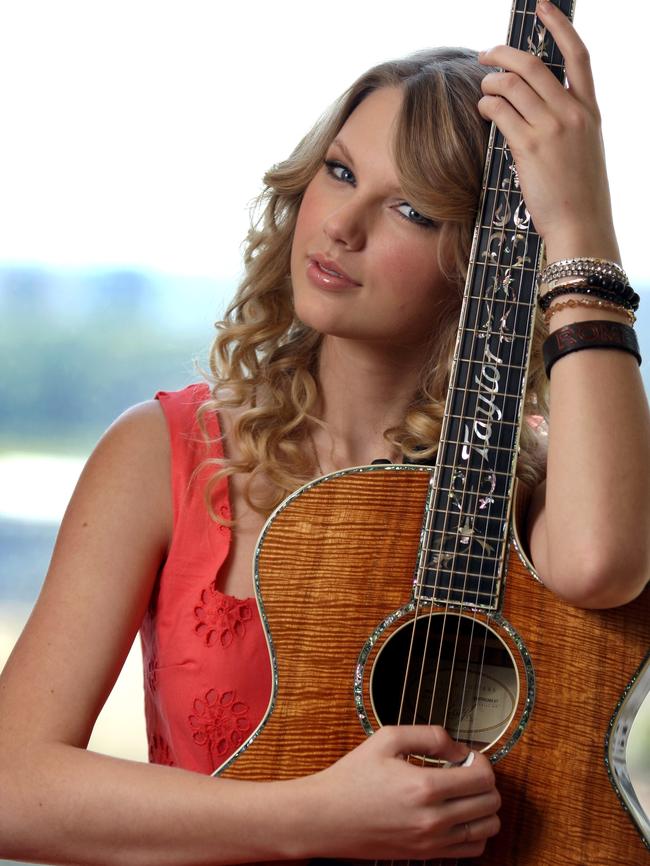

Cute, enterprising children stalking the streets of downtown Nashville in search of their big break was nothing new, and after being met with the industry equivalent of a shrug, the singer was savvy enough to realise that she needed a couple more tricks in her bag if she was to stand out from the crowd. The next time she visited, it was as a triple-threat: singer, songwriter, guitarist.

The music bug had bitten five years earlier, when she fell in love with the songs of country musician LeAnn Rimes, followed by some of the genre’s biggest-selling names of the 1990s, including Faith Hill, Shania Twain and the Dixie Chicks.

Soon she was overtaken by a fascination with how these artists used words and sounds to tell stories, exhibit emotions and create a transformative space for the listener to hear these songs with fresh ears and open hearts, as if they were looking in the mirror and seeing themselves.

None of this was achieved without persistence, though, for the great magic trick of timeless art is to make devilishly tough things seem effortless.

In a diary entry dated May 19, 2003, the 13-year-old wrote to herself: “I tried to practise my songs for Nashville, but I completely psyched myself out and broke down crying. I don’t know if I can do this. I want it so bad, but I get so scared of what might not happen.”

Born on December 13, 1989, Swift grew up in eastern Pennsylvania on a Christmas tree farm, which sounds made-up, like a biographical detail stolen from a Disney fairytale. Her parents had careers in finance, with her dad Scott working as a financial adviser for Merrill Lynch.

They named her Taylor because it was androgynous, which they saw as a potential advantage in the corporate world: her mum Andrea thought that if you received a business card bearing that name, you wouldn’t necessarily assume a gender before the meeting.

As her interest in competitive horseriding faltered and was replaced by an obsession with music, much of Swift’s spare time was devoted to sharing those burgeoning talents with anyone who would listen.

The precocious singer realised that performing the national anthem was the best way to get in front of a large group of people, and so she became very familiar with singing The Star-Spangled Banner at sporting events, first holding a microphone while performing to a backing track and later accompanying herself on an acoustic guitar.

In 2004, her parents moved Taylor and her younger brother Austin from Pennsylvania to Hendersonville, a spot chosen as it was only a 20-minute drive from downtown Nashville, where much of the power in US country music was centred.

Importantly, though, despite uprooting the family and shifting 1269km west of the Christmas tree farm, her parents applied zero pressure on her. They didn’t frame it as their daughter’s only shot at success; instead, it was proffered as moving to a nice community. If she made something of it? Great. But if not, that’s fine, too.

Besides, the musician was already piling plenty of pressure on herself. Restless ambition was her natural state, and sometimes she needed to talk herself down from hyperventilation to a more reasonable baseline.

That diary entry from May 2003 ended with a self-soothing note. “Relax,” she wrote. “Nashville is not going to kill me. I can handle it. I’m okay. I’ll be fine. I’m young. I’m talented. They’ll see it in me. I’ll be okay. I’ve got to hang on.”

The key to Swift’s success lies in her songwriting. By closely studying the likes of Rimes, Twain, Hill et al, then investing countless hours lost in the dream of penning her own lyrics, melodies and chord progressions that she hoped might speak to the souls of a million strangers, her artistic powers have grown accordingly.

When she signed a deal with Sony/ATV Tree Music Publishing in 2005 and became the youngest person the company had ever signed, she was determined not to be prejudged by her youth.

After school, she would visit studios on Music Row for writing opportunities set up by her publisher. “I knew every writer I wrote with was pretty much going to think, ‘I’m going to write a song for a 14-year-old today’,” she said in 2008. “So I would come into each meeting with five to 10 ideas that were solid. I wanted them to look at me as a person they were writing with, not a little kid.”

By using a combination of co-writing and solo writing, she has now published somewhere in the vicinity of 240 songs since issuing her self-titled debut album in 2006. (For quantitative comparison: The Beatles released about 220 songs in their recording career.)

The fodder for Swift’s songs has always been the stuff of life itself. With a novelist’s ear for literary flourishes and a journalist’s eye for detail, her curiosity about inner lives and her willingness to confess her emotional truths colour practically everything she has ever recorded.

By mining relationships and their failures for golden glimmers – based on both her own experiences, as well as her friends’ stories of their romantic travails – she struck a rich vein of material.

Hers is an articulate, self-deprecating, honest and highly relatable voice that first whispered directly into the ears of girls and young women, then to empathic young men – perhaps those seeking to better understand the fairer sex – then to their parents, then to their parents, to the point where today, the safest way to group Swift’s audience is with one word: humankind.

Growing up, her favourite love story was that of her maternal grandparents, who were married for 51 years and died a week apart while still madly in love in their 80s.

Her mum’s mum was Marjorie Finlay, a professional opera singer; coincidentally, her grandmother’s death in June 2003 occurred right around the time Swift was signing the development deal with RCA Records.

As one singer’s flame went out, another one was lit; in time, it would burn brighter and for longer than just about anyone expected. Anyone, that is, except for her father Scott, whose belief in his daughter was absolute. (“I never really went there in my mind that all of this was possible,” she told a Rolling Stone writer in 2012. “It’s just that my dad always did.”)

Her first single, Tim McGraw, was named after a US country superstar — undoubtedly a canny marketing move, but also a clever reference for an emerging artist, with its lyrics centred on memorialising a special song the singer shared with a high school boyfriend:

But when you think Tim McGraw

I hope you think my favourite song

The one we danced to all night long

The moon like a spotlight on the lake…

The final addition to her debut album was the ninth track, Should’ve Said No, which sticks out from the country arrangements with its rock ’n’ roll feel, big chorus melody and banjo picking placed prominently in the mix.

Written quickly and recorded on deadline, it was “about a guy who cheated on me and shouldn’t have, because I write songs,” she quipped in 2006, aged 16.

By now, this confessional aspect of her writing is both well-known and hard-earned. As far as break-up songs go, her 2012 track All Too Well remains a tour de force of the form that sparkles with artful, painful specifics about the end of a relationship:

But you keep my old scarf from that very first week

‘Cause it reminds you of innocence and it smells like me

You can’t get rid of it

‘Cause you remember it all too well

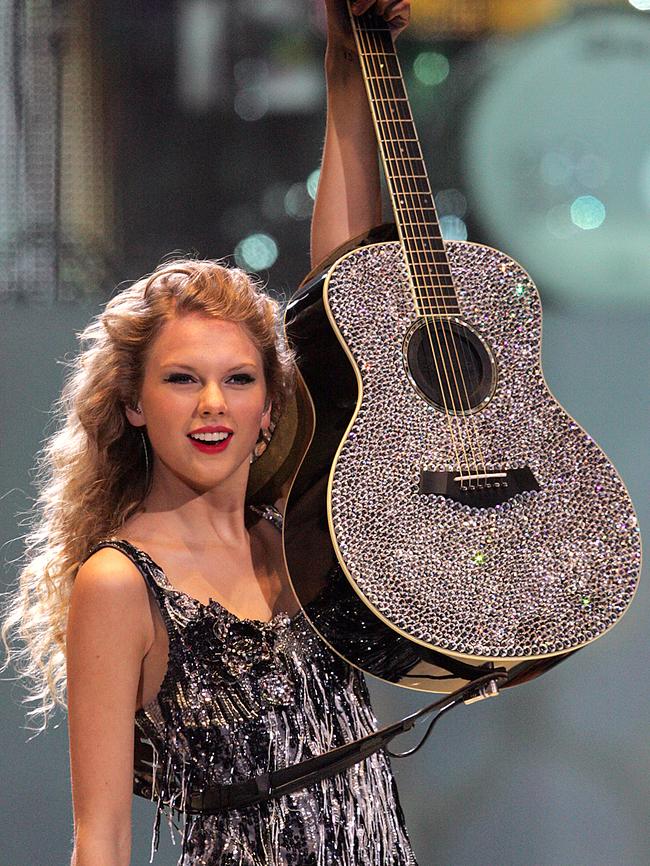

Four albums into her career, she began to realise there was no reason an award-winning country singer-songwriter couldn’t be a pop star, too.

Starting with 2012’s Red, she began leaning into pop sounds while keeping one foot in country. “At a certain point, if you chase two rabbits, you lose them both,” she noted in 2014. That was the year she fully embraced pure pop by working with platinum-eared Swede Max Martin on her fifth album 1989, so named for her birth year.

Swift’s well of smartly written, beautifully sung and hook-filled songs centred on romantic roller-coasters runs deep. Put plainly, she is popular because her songs and their subject matter speak to a great many people.

Given her diaristic style of writing, it is unfortunate – though perhaps not unexpected – that her undeniable musical credibility has sometimes been shrunk to tabloid-sized morsels of triviality about her personal life.

This is an unwelcome side effect of her success, and one that has seen her largely retreat from speaking with journalists, with a recent interview with Time Magazine – which named her its 2023 “person of the year” – a rare exception to her preference to communicate directly with her fans via carefully written social media statements.

As an artist, her mastery of craft is driven by three distinct traits: “I want to still have a sharp pen, and a thin skin, and an open heart,” she said in the 2020 documentary Miss Americana.

Two lesser-known compositions deserve to be highlighted here, however, both to show her emotional range and to rebut the misconception that her catalogue is one-dimensional.

The penultimate track on her second album, 2008’s Fearless, is a moving ode to her mum Andrea, her biggest supporter from when Taylor first began singing and, later, strumming:

And I love you for givin’ me your eyes

For staying back and watchin’ me shine

And I didn’t know if you knew

So I’m taking this chance to say

That I had the best day with you today

And perhaps the shiniest gem in her wide, deep discography is titled Ronan. First released in 2011, it’s another song about a boy, but it’s unlike anything else in her catalogue, because the boy in question died that same year, three days before he reached the age of four.

Swift never met him, but found her way to a blog written by Ronan’s mum, Maya Thompson, in the wake of his death from neuroblastoma. Struck by the power of Maya’s love for her boy, the songwriter shaped a four-minute narrative written from Maya’s perspective, and sought to share co-writing credit with Ronan’s grieving mum. She said yes.

Its lyrics are packed with emotional gut-punches, and for Swift to have written such a tender, delicate song – an eternal love story between a mother and a child – while in her early 20s was a feat of extraordinary empathy.

She has only performed the song live twice: first for a televised cancer fundraiser in 2011, before the song was released as a charity single; and then at a concert in Arizona in 2015, when Maya was in the audience with her family.

Completing the song without losing her composure was another remarkable feat of strength, particularly when, in its bridge, she sang a series of questions:

What if I’m standing in your closet trying to talk to you?

And what if I kept the hand-me-downs you won’t grow into?

And what if I really thought some miracle would see us through?

What if the miracle was even getting one moment with you?

It is an unfortunate universal truth that the tools required to gain greatness often prevent someone from enjoying their achievements. Yet it appears that, as her craft and popularity have each continued to ascend, Swift has learned to savour the ride and the fruits of her labour.

These realisations have come in waves, as the tides of public opinion have ebbed and flowed, both in her favour and against it.

In 2015, aged 25, she told a writer for GQ: “After 10 years, you learn to appreciate happiness when it happens, and that happiness is rare and fleeting, and that you’re not entitled to it. You know, during the first few years of your career, the only thing anyone says to you is, ‘Enjoy this. Just enjoy this.’ That’s all they ever tell you. And I finally know how to do that.”

In 2019, on the cusp of 30, she wrote in an article for Elle magazine: “I remember people asking me, ‘What are you gonna write about if you ever get happy?’ There’s a common misconception that artists have to be miserable in order to make good art, that art and suffering go hand-in-hand. I’m really grateful to have learned this isn’t true. Finding happiness and inspiration at the same time has been really cool.”

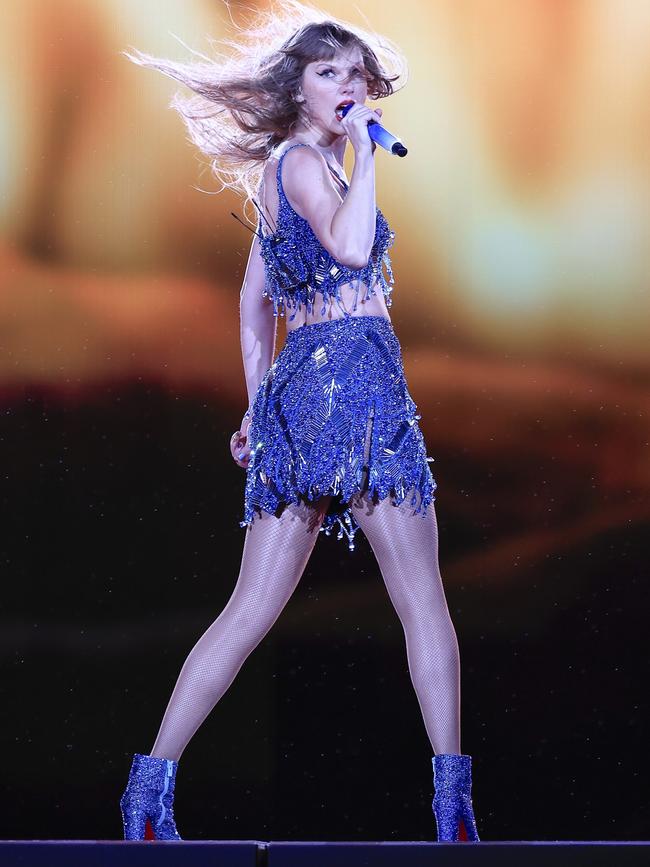

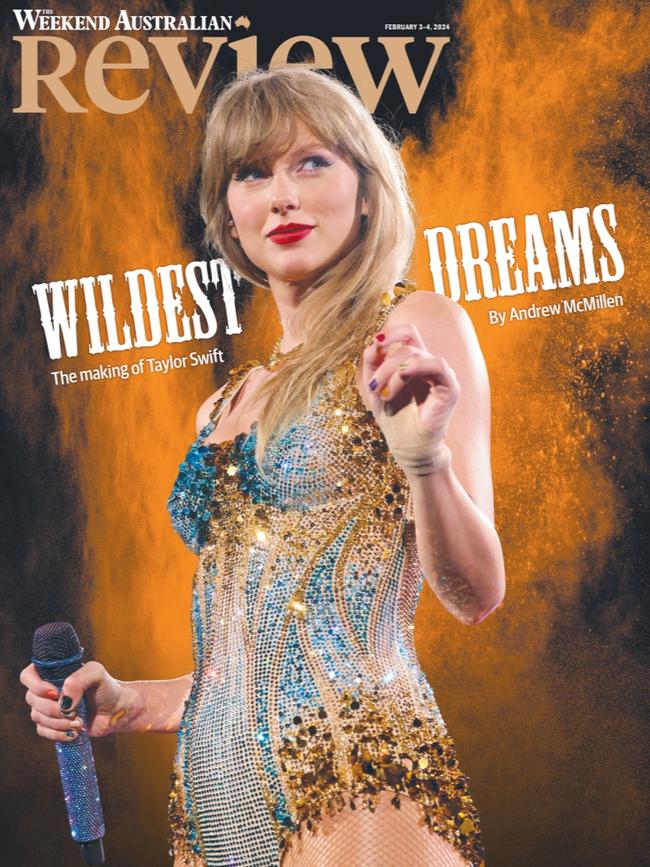

And in a recent podcast interview about Swift’s record-breaking Eras tour – which touches down in Australia this month, for seven sold-out stadium shows before about 630,000 fans – her global promoter Louis Messina said: “She is Iron Woman. She’s having the best time of her life.”

“The few times that I’ve spoken to her, she’s coming off stage and she’s as happy as can be,” said Messina, who has worked with Swift for 17 years. “She’s singing three hours and 20 minutes every night, sometimes doing three, four, five (nights) in a row. I tell her she’s bionic, and she really is: I’ve never seen anyone like her in my whole career.”

As Swift has vaulted into the pantheon of generation-defining pop stars, she has overcome her fair share of obstacles.

Perhaps the biggest of these was the situation in 2019 wherein her former record label boss, Scott Borchetta, sold his label Big Machine Records – and with it, the masters to her first six albums – for about $US330m ($500m) to a company led by Scooter Braun, an artist manager against whom Swift alleged “incessant, manipulative bullying I’ve received at his hands for years”.

The whole affair was wounding, but rather than rage against Big Machine and the catalogue sale – something beyond her control – Swift decided to get to work.

The obstacle became the way: she turned a negative into a positive by re-recording and re-releasing those albums, and appending a revised title in brackets to each reissue, starting with Fearless (Taylor’s Version) in February 2021 and most recently with 1989 (Taylor’s Version) in October. That leaves only her debut and 2017’s Reputation yet to be reissued.

Rather than purely looking backwards, though, she has continued to release new music in parallel.

More than any other popular artist, Swift used the enforced pause of the pandemic to reinvigorate her artistry: she released two albums in 2020, titled Folklore and Evermore, on which she partnered with a new collaborator in Aaron Dessner, who just so happened to have in hand a swag of quieter, folkier instrumental songs well suited to a creative left turn. And in 2022, she returned to sleek pop with Midnights, her 10th album.

The dual effect of these efforts – issuing three new albums and four re-records of earlier work – has been to keep the singer-songwriter almost constantly in public view since 2020, while also introducing her older material to a new generation of listeners.

Combine that with her return to the concert stage last March with the Eras Tour – which will span 151 shows across nearly two years by the time it concludes in December, having broken box office records to become the first tour to surpass $US1bn ($1.5bn) in revenue – and she is undoubtedly riding a king tide.

Media confection or not, Time’s assessment of Swift as its “person of 2023” is hard to argue against, given how omnipresent she has been of late, with almost all of the attention centred on her musicianship and her public performance of same.

Now 34, she is an artist who wanted success so bad it hurt, and was willing to spend every waking moment from age 11 to rise above the noise to achieve that rare triad: commercially peerless, critically acclaimed, and ardently adored by the masses.

None of it was done by accident, nor without sacrifice and persistence. Her story is one of true grit, dedication and self-belief, accomplished while wielding those three prized assets: sharp pen, thin skin, open heart.

Taylor Swift will perform in Melbourne (MCG, February 16-18) and Sydney (Accor Stadium, February 23-26).

More Coverage

Andrew McMillen is an award-winning journalist and author based in Brisbane. Since January 2018, he has worked as national music writer at The Australian. Previously, his feature writing has been published in The New York Times, Rolling Stone and GQ. He won the feature writing category at the Queensland Clarion Awards in 2017 for a story published in The Weekend Australian Magazine, and won the freelance journalism category at the Queensland Clarion Awards from 2015–2017. In 2014, UQP published his book Talking Smack: Honest Conversations About Drugs, a collection of stories that featured 14 prominent Australian musicians.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout