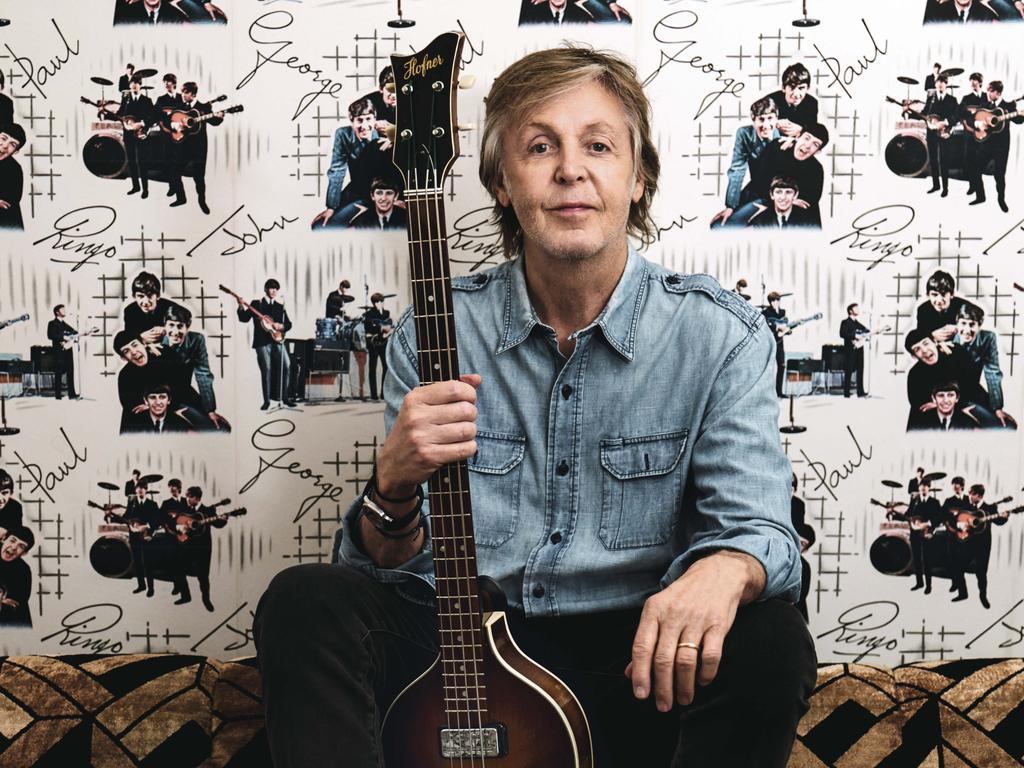

Exclusive interview with Paul McCartney on Got Back 2023 Australian tour

Since the early days of The Beatles, the much-loved star has been haunted by a recurring nightmare. But ahead of his Australian tour, has he finally waved goodbye to that troubling dream?

Growing up, Paul McCartney was encouraged by his father to put three letters at the forefront of his mind: D-I-N, representing the snappy parental entreaty to Do It Now.

This was well before he began playing in a rock ‘n’ roll group whose music swept the globe and changed the face of popular culture. Instead, what McCartney Sr was attempting to instil in Paul and his younger brother was to avoid procrastination.

“What he meant was, if you’ve got something to do, don’t put it off till tomorrow,” McCartney says. “If you’ve got your homework, and you’re trying to watch telly, he’d say, ‘Do it now.’ And he was right. It was a good’un.”

Since he and his bandmates started performing as The Beatles in 1960, aged 18, procrastination has rarely seemed to trouble the British singer, songwriter, bassist and pianist, whose artistic drive remains formidable.

Aged 81, he will soon return to Australia, which is why he connects exclusively with Review in late July. “You could say coming back to Australia is a D-I-N; that’s something I’ve been wanting to do,” he says with a sly smile. “So yeah, that’s a bit of a D-I-N.”

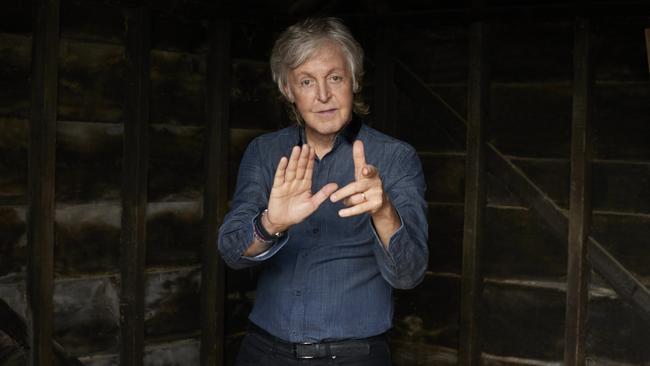

One of the world’s most famous faces is peering down at his laptop from a wooden loft in Long Island, New York. The video isn’t for publication, so he’s comfortably dressed down for this audience of one; unshaven and wearing a white T-shirt, he is a man at ease who smiles often, responds thoughtfully, and gestures expressively with the two hands that helped write music history.

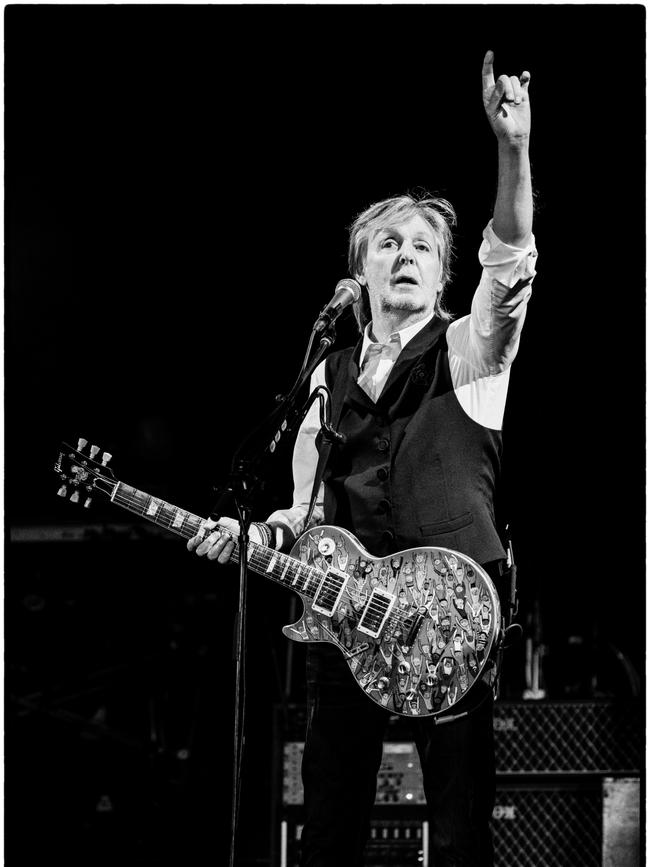

It is almost six years since he last visited Australia, in late 2017, for a series of sublime shows stacked with hits and delivered with verve. His world tour played to about 900,000 people that year, grossing US$132m ($198m), according to trade publication Pollstar.

After a pandemic pause, McCartney returned to touring US stadiums last year. In June, a week after his 80th birthday, he and his band headlined Glastonbury Festival in his home country.

Before a crowd of about 100,000, their set spanned three hours, featured cameos from Bruce Springsteen and Dave Grohl, and evoked superlatives from anyone in earshot or watching at home on BBC TV. Clearly, this is a man who performs because he loves it.

“I set out to be a musician, and I learned guitar, and wanted to write songs and make records,” says McCartney. “So you do that, and then you get to perform for people, and you get a love affair with it. You kind of get addicted to it. That’s one of the things that you get addicted to; the warmth that comes back from the audience is very special.”

“Warmth” is a curious choice of word that calls to mind the calming scene of a lit fireplace at home on a winter’s night. What McCartney and his former bandmates unintentionally lit with their audience six decades ago soon grew into something more akin to a towering inferno.

When The Beatles landed in Australia in June 1964, what met them in Adelaide was an estimated 300,000 people – roughly half of the city’s population – turning out to greet them on the 6km route between the airport and city centre.

The figure sounds like the fancifully far-fetched work of a publicist’s fantastical fever dream until you review news footage captured at the city locale, where police officers struggled to contain the huge crowds surrounding the motorcade and, later, outside the band’s hotel.

“Are you going to be able to get out, or are you going to have to be locked in your rooms all the time?” a reporter asked.

“We don’t really know,” replied McCartney, “until we get to wherever we’re going.”

It was an auspicious Australian debut, and when asked what he recalls of that Adelaide arrival 59 years prior, he neatly encapsulates it with one word. “Mayhem,” he says with a smile. “It was just crazy. We never knew whether the Aussies are going to like us, or how much they knew about us. We came in not knowing, but pretty soon found out. They were crazy, and it was really great. Nobody minds a bit of adulation!”

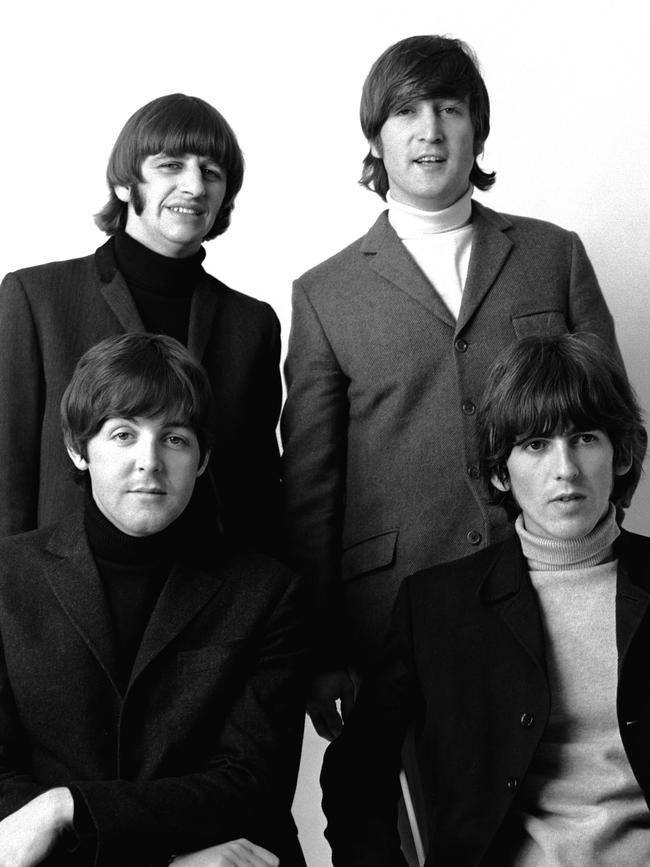

The Beatles’ one and only Australian tour – fortuitously booked a year in advance by entrepreneur Kenn Brodziak, before most of the world had heard their music – comprised 20 half-hour sets performed in four cities. Drummer Ringo Starr’s diagnosis of tonsillitis sidelined him for the first two dates in Adelaide, with Jimmie Nicol replacing him behind the kit until Starr resumed duties in Melbourne.

With the benefit of many years’ hindsight, what does McCartney make of Beatlemania? What prompted so many people to turn out on a Friday in the South Australian capital to crane their necks for a look at four young British musicians?

“I don’t know,” he replies. “I think when The Beatles came out, it had been a pretty lean period up till then for young people. And so suddenly, we came on the scene and struck a chord with a lot of young people; they thought that we thought similar to them, and I don’t know, was there a cocky attitude or something? And hey – the music wasn’t bad. So all of that combined. They got really excited, which is great for us; it’s what you want.”

When he returns to Australia in October, McCartney and co will begin with an indoor show at the Adelaide Entertainment Centre for about 6500 people – a comparatively small number that counts as an intimate warm-up show, by his standards.

Backed by the four musicians of his longtime band, who have been at McCartney’s side for more than 500 shows in 20 years, the tour will move on to outdoor venues whose capacities range from 22,500 (Heritage Bank Stadium at the Gold Coast) to about 53,000 (Melbourne’s Marvel Stadium).

Playing to those big crowds remains an enticing prospect for the band leader. “I must admit, talking about the warmth of the audience, I was trying to work out once why people get nervous, and why I used to get nervous,” he says. “I think it is because you think the crowd may not like you. So there’s actors and stuff going, ‘Oh my god, I’m doing Shakespeare, they’re gonna hate me…’ And so you get nervous.

“After a while, I started to think, ‘Wait a minute, these people have paid to come and see me. They don’t hate me! In fact, I love them, and they love me!’”

“That takes the edge off it and you normally have a good evening,” he says. “We normally have a really good party. I’m exhausted by the end of it – but it’s worth it.”

Toward the end of 2021, something unusual happened: The Beatles burst back to life on the world’s television screens, as if suddenly let loose from a newly excavated time capsule and reanimated as the four dashing, witty and creative young men they had been more than five decades prior.

Having given up touring in 1966 and instead devoted themselves to the recording studio, the band began 1969 at a soundstage in Twickenham – and later, inside their own Apple Corps headquarters on Savile Row, Mayfair – while attempting to write and record a new album. Cameras and recording equipment were set up to capture what took place in the month of January.

The plan was to issue a feature film that would conclude with a live performance, location unknown.

But unbeknown to all, director Michael Lindsay-Hogg and his crew were rolling during what would become one of the final recording sessions for the band, and its very last concert, held on the Apple rooftop for a curious crowd on the street five storeys below.

As with the album Let It Be, Lindsay-Hogg’s 80-minute documentary film was released in May 1970. It shared the same name, but his edit narrowed the scope of footage to focus only on the fractious end of the world’s most popular band, thereby leaving much on the cutting room floor.

It took an excavator named Peter Jackson – the film director best known for his work on The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit film series – to review the pictures and audio anew, and offer a revisionist take on a history that had seemed to be cast in stone.

Released on the Disney Plus streaming service in December 2021, Jackson’s painstakingly constructed docuseries, titled The Beatles: Get Back, was a global revelation. Across three episodes, its nearly eight-hour runtime offered a moving and absorbing portrait of four artists contending against the clock, and other distractions, to create new work under pressure.

It swiftly became the major topic of conversation among serious music fans, and even McCartney – who appeared on screen as much as anyone, and who was credited as an executive producer – was swept up by the way in which his old band re-entered the public consciousness.

Asked whether he was surprised by the impact that the Get Back series had on release, he replies, “I was very happy with the impact. But once I’d seen what Peter Jackson had done, and how it was all being handled by Disney, I wasn’t as surprised as I thought I might be, because he’d done such a great job. He’d restored the film, and he’d gone through 56 hours so patiently and brought this thing to the screens.

“For me though, the main thing was it really made me happy, because I’d seen the original Let It Be film, and that was more focused on the break-up of The Beatles. So it wasn’t as happy as this one was. This is still around that time, but it shows a lot of our working methods, and the process.

“It made me very happy, that series,” says McCartney. “I loved it. And then when people talked about it a lot and said they liked it, it was great – because I kind of worried, to tell you the truth, that I would come off a bit bossy. Because I often would try and hold the session together, or try and encourage everyone, ‘Come on guys, we’ve only got a week to learn this song…’ or whatever.

“But then seeing it, it was like – no, it wasn’t,” he continues. “That was just the way we worked. And there was such great humour in it; me and John (Lennon) were having a right laugh. I mean, for people who were supposed to be delivering these songs that they hadn’t written yet, and didn’t know, in like a month’s time, and put on a live show – we were messing around. You think we’d be a bit more serious. In the end, I thought it was a brilliant way to do it. If you’re going to rehearse, don’t make it too serious; do the work, but have a laugh.”

One of many diamonds unearthed by Jackson and his team was a quiet moment where McCartney began composing the song Get Back out of thin air, as he sat plonking away on his bass guitar and humming to himself.

Soon, he showed the nascent sketch to Starr and George Harrison, who sat listening, appearing to be bored – the guitarist yawned widely – before their creative minds began to latch on to the new idea.

By the time Lennon stalked in late, sat down with his guitar and locked into the rhythm, it had begun to take shape as the band’s new single, which would later become one of the Beatles’ many indelible compositions.

Asked about the strange experience of watching that lightning bolt of inspiration strike him all those years later, McCartney replies, “It was great, really, because I thought it happened like that. But it was so long ago that I wasn’t absolutely sure. And then Peter Jackson sent me a text. He said, ‘Did you write Get Back before you went in the studio, or did you make it up on the spot?’ And he sent me a little bit of film, of me making it up on the spot. And I said, ‘No, I had no idea before I came in; what you have on film there, that’s the birth of Get Back’. That was a nice moment.”

More than most of his peers, McCartney seems to enjoy being caught in the rip-tide of history. The past few Covid-affected years have seen him alternate between works new and old, and so long as there’s enough of the former at play, he appears unbothered by the inevitable tug of the latter; chiefly, his titanic achievements with Lennon, Starr and Harrison.

He continues to challenge himself and his audience with new music, most recently on his 2020 album release McCartney III, recorded at a studio near his home while in lockdown, or “rockdown”, as he prefers to call it. (Review’s critic Phil Stafford described it as “a melange of whimsy, multi-instrumental prowess, storytelling, social commentary, gardening tips and toilet humour,” and awarded it four stars.)

He has published two titles in the Hey Grandude! series, around which Review last spoke with McCartney, as the author of his debut illustrated children’s book.

“It’s like a holiday from your day job,” he said in 2019. “I’ve got my touring, which I love – or I wouldn’t do it – and then I’ve got something like Grandude, which is almost like a hobby.”

As well, he has released two books canvassing his distant past, including 2021’s The Lyrics – soon to be accompanied by a podcast – and a recently released photo book, titled Eyes of the Storm. It’s based on McCartney’s work behind the camera as The Beatles toured the world in 1963-1964, and a collection of these photos is currently showing at London’s National Portrait Gallery until October 1.

Yet rather than camping out purely in the past, he’s simultaneously pushing against the limits of his artistic abilities, by performing three-hour concerts. “You can never rest on your laurels,” he has said previously. “And it’s just as well really. I don’t particularly want to rest on them. It’s probably why I’m touring, making new albums.

“I don’t actually want to be a living legend,” McCartney told author Paul Du Noyer more than 30 years ago. “I came in (to) this to get out of having a job. And to pull birds. And I pulled quite a few birds, and got out of having a job, so you know, that’s where I am still.”

As far back as 1989, when he was aged 47, he has been asked whether a particular run of shows might be his last.

“It’s never the last tour as far as I’m concerned,” he told Du Noyer. “It’s tempting to say ‘Yeah’, and get them all to come, like a lot of people do. But I never think it’s my last tour. I’ve always said I’ll be wheeled on when I’m 90. And that might be a dreadful prediction that comes true.”

Since the early days of The Beatles, McCartney has been plagued by a recurring dream where he is on stage and notices the audience beginning to leave. At first he tells himself they’re heading out to get a beer, and doesn’t mind so much – yet no matter which certified crowd-pleasing song he plays, they keep heading for the exit.

“They’re leaving in droves, and it’s like, ‘No, come back!’” he remembers. “And you can’t say to yourself, ‘Wait a minute, it’s only a dream’, because sometimes dreams seem really realistic.”

He invariably woke in a cold sweat from this classic performers’ nightmare, shaken by the fear of a crowd no longer interested in hearing him sing and play, despite all evidence to the contrary. Perhaps subconsciously, it’s part of what has kept him sharp and hungry across the years.

But when reminded of those troubled dreams of a younger man, McCartney laughs and shares some happier news befitting his station in life today. “I haven’t had one of those recently,” he says. “That was more of a nightmare of mine than it is now. I think I’ve maybe said goodbye to that one. I hope so.”

There is something oddly satisfying about a performer of his renown spending decades being haunted by the spectre of things going badly wrong, before finding relief from those fears in later life. It’s more than enough to make a man want to get back on stage and do it, now.

Paul McCartney’s Got Back Tour starts in Adelaide (October 18), followed by Melbourne (Oct 21), Newcastle (Oct 24), Sydney (Oct 27), Brisbane (Nov 1) and Gold Coast (Nov 4).

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout