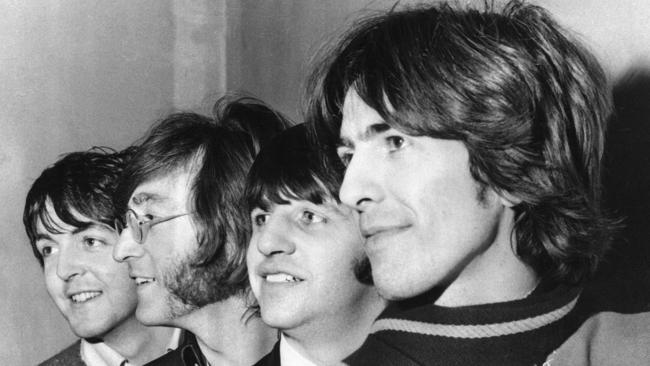

Blank canvas: The Beatles’ White Album 50 years on

The ‘White Album’ had a complex birth with The Beatles navigating myriad challenges, but the band, at least, loved the result.

The Beatles had managed to squeeze a fair bit into the years leading up to 1968. The four members of the Liverpudlian group had variously quit touring; received death threats after one of them described the group as being more popular than the son of God; partaken of the psychedelic drug LSD; and spoken cautiously to the press about its mind-expanding effects.

They had also written and recorded one of the greatest albums in the history of popular music, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band; offended first lady Imelda Marcos by refusing to attend a social engagement on their only visit to The Philippines; found solace in transcendental meditation in India; grieved for the sudden death of their long-time manager; shot and edited a largely unscripted colour film that was screened on the BBC in black-and-white, and widely panned; launched a publishing and record company named Apple Corps; and sailed around the Greek islands with heads full of acid, strumming ukuleles, chanting “Hare Krishna” for hours on end, with plans of buying an island so they could live communally as a band, with their four houses connected by tunnels leading to a central glass dome.

Having conquered the world of pop, the quartet — whose members were aged between 25 and 28 in 1968 — were keen on separating themselves from the rest of humanity by building their own utopia. “I’m not worried about the political situation in Greece as long as it doesn’t affect us,” John Lennon said in 1967, the year a military junta took power in Athens. “I don’t care if the government is all fascist or communist. I don’t care.”

That trip ended with a hollow thud, as trips tend to do. So did that idealistic vision of four young men living together in isolation and in harmony, with their families and members of their inner circle.

“It came to nothing,” said Ringo Starr. “We didn’t buy an island, we came home. We were great at going on holiday with big ideas, but we never carried them out …

“That was what happened when we got out. It was safer making records, because once they let us out, we’d just go barmy.”

Lennon, in particular, seemed to be phasing in and out of reality with greater frequency than the other three. Paul McCartney recalled him proposing that all four Beatles try trepanning, the ancient surgical intervention of drilling a hole into the skull in order to release pressure on the brain.

His bandmate demurred, suggesting Lennon try it first — and if it worked out well, they’d all follow his lead. “That was the only way to get rid of John’s madcap schemes, otherwise he would have had us all with holes in our heads the next morning,” said McCartney.

Stranger still was the occasion when Lennon called an emergency meeting at the band’s Apple Corps headquarters. The agenda contained just one item. “Right,” he said, sitting behind his desk. “I’ve something very important to tell you all. I am … Jesus Christ. I have come back again. This is my thing.”

In response, Lennon’s audience — his three bandmates plus publicist Derek Taylor and Neil Aspinall, Apple’s managing director — said little, according to one account of this meeting.

After an awkward pause, wherein the new Messiah was not cross-examined, it was suggested they adjourn to a restaurant for lunch.

There, Lennon matter-of-factly informed a well-wishing fan of his new identity.

“Oh, really?” replied the man. “Well, I liked your last record.”

■ ■ ■

The recording sessions for the band’s ninth studio album — self-titled, but which would come to be popularly known as the White Album — began in late May 1968.

After chewing up months experimenting with ventures such as the Apple record company and the Apple boutique in central London, the musicians eventually returned to what they were best at.

“It was a problem with the hippie period — particularly with reefer — that you’d sit around and think of all these great ideas, but nobody actually did anything,” said George Harrison.

“Or if they did do something, then a lot of the time it was a failure. The idea of it was much better than the reality. It was easy to sit around thinking of groovy ideas, but to put them into reality was something else. We couldn’t, because we weren’t businessmen. All we knew was hanging around studios, making up tunes.”

As with almost all of their previously recorded material, the venue was EMI’s Abbey Road studios in London. They were armed with a swag of demos of songs written largely at the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s retreat in Rishikesh, north India. This collection was to feature the most diverse writing credits of any entirely self-composed Beatles album to date.

“We wrote about 30 new songs between us,” Lennon said in 1968. “Paul must have done about a dozen. George says he’s got six, and I wrote 15. And look what meditation did for Ringo — after all this time he wrote his first song.” He was referring to Don’t Pass Me By.

As ever, originality was a goal in itself.

“When we started, I don’t think we thought about whether the White Album would do as well as Sgt Pepper — I don’t think we ever really concerned ourselves with the previous record and how many it had sold,” Harrison said. “In the early 60s, whoever had a hit single would try to make the next record sound as close to it as possible — but we always tried to make things different. Things were always different, anyway — in just a matter of months we’d changed in so many ways there was no chance of a new record ever being like the previous one.”

Despite inarguably occupying popular culture’s pole position — with Sgt Pepper having spent a record 27 weeks atop the British album charts and 15 weeks at No 1 in the US — the band was still wary of what the competition was up to.

The blistering groove and propulsive energy of Helter Skelter, for instance, was sculpted by McCartney after he read a magazine article in which the Who’s guitarist Pete Townshend described having written “the dirtiest, filthiest rock ’n’ roll song ever”. The very idea pushed the band to record dozens of takes of what remains among its sharpest compositions, even though McCartney had not heard the Who’s new work.

However, the four young men had spent their entire adult lives in each other’s pockets, and the prolonged creative process that drove the recording of The Beatles allowed personality traits that had once chafed to become scratched red-raw. Freed from any meaningful budgetary constraints, the musicians were moved to spend hundreds of hours in the studio, finessing the arrangements, arguing over which sounds belonged where, and regularly wiping the previous day’s work in favour of newer, stronger ideas.

To call it a fraught recording environment would be an understatement. Ringo Starr, producer George Martin and chief engineer Geoff Emerick each left the project at various points between May and October 1968, each suggesting he’d had enough of the stifling atmosphere inside the Abbey Road studios.

Starr’s departure to Sardinia with his family sent a shock through the remaining three, who perhaps recognised they’d been taking his dependable presence for granted for too long.

“I left because I felt two things,” Starr later reflected. “I felt I wasn’t playing great, and I also felt that the other three were really happy and I was an outsider.”

His band mates realised that what their friend needed most was reassurance. “Ringo felt insecure and he left, so we told him, ‘Look, man, you are the best drummer in the world for us’,” McCartney said. “He said ‘Thank you’, and I think he was pleased to hear it. We ordered millions of flowers and there was a big celebration to welcome him back to the studio.”

■ ■ ■

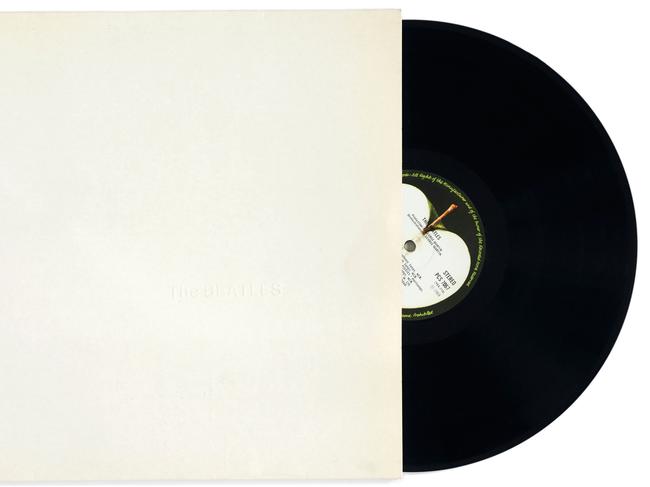

After the busy, colourful artwork that set the tone for the music heard on Sgt Pepper, McCartney enlisted British pop artist Robert Hamilton to design the cover sleeve for The Beatles. It was Hamilton’s work that would give the double album its colloquial name — he came up with an idea for a pure white sleeve, with the band’s name embossed in a small font near the centre.

In effect, the cover was a blank canvas on to which the world’s pop music fans could project their expectations before they had even heard the opening track. With the album’s 30 songs and a total running time of 93 minutes, recorded across five sometimes fractious months, however, for the first time in the history of the Beatles, quality was taking a back seat to quantity.

Even Martin — the band’s long-time creative adviser who had been in the producer’s chair since the Beatles’ 1962 debut on EMI’s Parlophone label — was unable to convince them to edit the album down to a single vinyl disc. “They came in with a whole welter of songs — I think there were over 30, actually — and I was a bit overwhelmed by them, and yet underwhelmed at the same time because some of them weren’t great,” Martin said.

“I thought we should probably have made a very, very good single album rather than a double. But they insisted. I think it could have been made fantastically good if it had been compressed a bit and condensed.”

The Beatles, then, offers a fascinating melange of majesty and mediocrity.

For every gorgeous arrangement such as Blackbird, While My Guitar Gently Weeps, Dear Prudence or Julia, there are several tracks that wouldn’t rate a mention among the group’s top 100 compositions. Only complete obsessives or compulsive liars could claim to love every note of music on it.

Even the songwriters second-guessed their creative decisions after its release. “There was a lot of ego in the band, and there were a lot of songs that maybe should have been elbowed or made into B sides,” Harrison noted.

Starr concurred: “There was a lot of information on the double album, but I agree that we should have put it out as two separate albums: the ‘White’ and ‘Whiter’ albums,” he said.

Yet overall, the drummer retains a fondness for the diverse collection. “Sgt Pepper did its thing — it was the album of the decade, or the century maybe,” he says. “It was very innovative, with great songs, it was a real pleasure and I’m glad I was on it — but the White Album ended up a better album for me.”

His opinion was shared by Lennon. “I always preferred it to all the other albums, including Pepper, because I thought the music was better,” he said in 1972. “The Pepper myth is bigger, but the music on the White Album is far superior. I wrote a lot of good shit on that. I like all the stuff I did, and the other stuff as well.”

McCartney, too, regards it as a fine work and points to its diversity of arrangements as a strength rather than a weakness. “I think it was a very good album,” he says. “It stood up, but it wasn’t a pleasant one to make. Then again, sometimes those things work for your art.”

Hindsight might tempt us to see the end of the Beatles in 1970 as inevitable.

Viewed through another lens, though, isn’t it remarkable that four men were able to remain so productive for so long, recording 12 studio albums comprising more than 200 songs across eight years?

After the release of The Beatles on November 22, 1968, what lay ahead for the band was a final live performance on the Apple Corps rooftop in London; a superb album titled Abbey Road; the announcement of its break-up; the release of a final studio album, Let It Be, which was recorded before Abbey Road but arrived a few weeks after the band broke up; the pursuit of solo recording careers, with varying success; interminable chatter, debate and conspiracy theories about the minutiae surrounding its entire oeuvre; Lennon’s murder by a gunman in 1980; Harrison’s death from lung cancer in 2001; knighthoods for the surviving members; the ongoing touring efforts of McCartney in stadiums and Starr in theatres; total global record sales estimated to be in excess of 800 million; endless remixing, remastering and re-release of albums on the eve of significant anniversaries; and the undeniable immortality that comes with touching so many people through the creation of timeless music.

The Beatles 50th anniversary release is available now via EMI Music Australia.

-

MIDDLE EIGHT

Five White Album factoids that may have passed you by:

1. Nobody took George Harrison’s song While My Guitar Gently Weeps seriously until he enlisted Eric Clapton to play that famous electric guitar solo. At first, Clapton demurred — ”Nobody’s ever played on a Beatles record and the others wouldn’t like it,” he told Harrison — but when the guitarist arrived at Abbey Road, at the songwriter’s insistence, his presence forced Paul McCartney and John Lennon to play nice. “Just bringing a stranger in amongst us made everybody cool out,” said Harrison.

2. That song was written as an experiment after Harrison opened a book at his mother’s house at random; the first phrase he saw was “gently weeps”. Similarly, Lennon’s Happiness is a Warm Gun came about after producer George Martin showed him a magazine cover featuring that slogan. “I thought it was a fantastic, insane thing to say,” said Lennon in 1971. “A warm gun means you’ve just shot something.”

3. In Japanese, “Ringo” means “apple” — which was also the name of the band’s record company.

4. McCartney wrote Why Don’t We Do It in the Road? after observing monkeys mating in India. “A male just hopped on to the back of this female and gave her one, as they say in the vernacular,” he later noted. “And I thought, bloody hell, that puts it all into a cocked hat, that’s how simple the act of procreation is, this bloody monkey just hopping on and hopping off. There is an urge, they do it, and it’s done with. And it’s that simple. We have horrendous problems with it, and yet animals don’t.”

5. Revolution 9 was, is and will forever be impenetrable garbage — despite the fact Lennon claimed to have spent more time on that eight-minute experimental sound collage “than I did on half the songs I ever wrote”, as he noted in 1970. (But you already knew that, right? Be honest: when was the last time you listened to it all the way through, sober, and enjoyed it?)

I’ll leave the final word on the White Album to McCartney, who made the following observation 50 years ago: “People seem to think that everything we say and do and sing is a political statement, but it isn’t. In the end it is always only a song. One or two of the tracks will make some people wonder what we are doing — but what we are doing is just singing songs.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout