Midnight Oil: “Bones Hillman was keeping a terrible secret from us”

Midnight Oil’s long-time bassist and co-vocalist Bones Hillman, who died of cancer at 62, kept details of his illness from those nearest to him.

When Midnight Oil announced last Sunday that long-time bassist and co-vocalist Bones Hillman had died of cancer, aged 62, the news came as a sudden shock to fans around the world. Neither band nor bassist had given even the slightest hint that anything was amiss in Hillman’s world, with his absence from recent media appearances — including a Review cover story in late September — taken to be a result of him being based in Milwaukee and unable to travel here because of the pandemic.

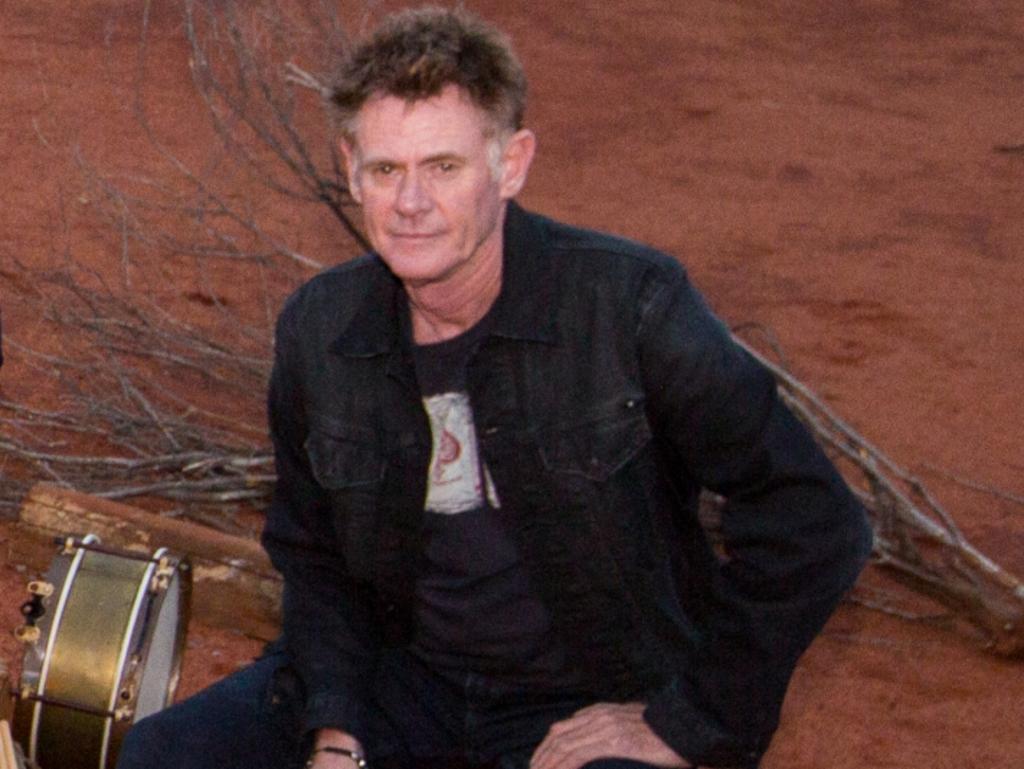

On Wednesday I spoke with the band’s drummer, songwriter and co-vocalist, Rob Hirst, whose grief was palpable.

Andrew: Do you want me to ask you questions, or do you just want to riff to start with?

Rob: I haven’t got long; I’m heading up north, getting out of town for a bit. But I was going to say, one of the great joys with Bonesy was, from a drumming point of view on stage, he’d sing these amazing harmonies and then he’d come back and just pull a face or tell me a joke on stage. He lightened the whole thing, and it was so lovely to have that input on stage, and that camaraderie and friendship. My drummer friend Mark Marriott — who plays with my daughter, Jay [O’Shea], in Australia — said it best when he texted me the other day. He said, ‘a brother in the engine room is a connection beyond words’, and I think only people who play in rhythm sections can understand what he’s talking about.

Yeah, I’ve really been thinking about that. I mean, all of you are feeling his loss, but the relationship between any drummer and bass player is absolutely consequential to everything else that happens within a band. Thinking of all the times that you’ve been on a stage with him — looking over to your left, I guess — what are some of the memories that come to mind? Has he just been that endlessly reliable guy who was always there for you?

Yeah, endlessly reliable. I mean, he’s one of those singers that can actually pull a note out of thin air and hit it right on the nail. He doesn’t slide up to the note, he doesn’t slide down; he just hits it. Bang. With Midnight Oil, we play pretty hard, but we also do a lot of harmony work, [and] choruses. And when Bonesy joined, we could do that so much more, because of the power and the range of his voice, and the fact that he was so consistent.

So what I used to do… Everyone’s got their own wedge [monitor] or their own in-ears. I’m very old school; I still have a wedge, I don’t use in-ears. So I used to have very little bit of my kick drum in my wedge, to lock in with Bonesy’s bass, which it did, effortlessly. And the other thing I’d always have in is a lot of Bones’s vocal, so that when I pitched, I pitched to Bones, because I knew that he was right on the note. So for all the years together, he was the one that kept my increasingly ragged asthmatic bleat in tune. [laughs]

Did it bother you that he didn’t seem to lose his tone, while you did?

Oh, I’m so glad that he didn’t. [laughs] And in the recording studio, similarly, we were able to do things with our producers, Warne Livesey and Nick Launay, which we couldn’t do before, just because of the power of Bones’s groove. He’s a really groove-y bass player, and that’s the thing. Like all Kiwis who came after The Beatles, he was Beatles-obsessed, and of course with The Beatles it was all about vocals and harmonies, and so he came with that tradition. We were so lucky to find him at the time of our playing life when we really wanted to expand that side of the band.

I’ve been spending a lot of time in the last few days listening back to [1993 album] Earth and Sun and Moon, and the harmony work there is just incredible. What do you recall about the writing and the arranging of the harmonies, in particular, on those songs?

It’s the way Jim and I write, mainly; we’re pretty much melody-obsessed and always have been. We figured out whose range went where, and Bonesy would almost always take the highest line; I’d take a middle line, and Pete would sing a melody, of course. And then sometimes Jim would sneak in a really interesting harmony between all the others, because we actually had four singers. And actually five, because Martin even chimed in occasionally on stage. It became very much a vocal thing.

Back in the pub days, vocals were hard to get over the Sturm und Drang of the noise and the amps; those hot and sweaty pubs were hard to get vocals above a band. But as we got onto bigger stages and sound systems got better, it really suited us, because then we could really actually hear ourselves singing. And particularly when we did the unplugged album [in 1993], when we recorded that album over in New York City, I heard things I’d never heard before, just because everyone was playing softly. Martin and Jim were on acoustics [guitars], Chris Abrahams playing piano, of course I was on brushes, we had a percussionist [named] Basheri playing with us, and Bonesy playing acoustic bass. I could hear all this great stuff and I thought, ‘Wow, this band can really sing!’ [laughs]

There’s several songs on Earth and Sun and Moon that really stand out to me in terms of vocal harmonies, but probably the greatest of those is Outbreak of Love. And towards the end of that, I guess there’s at least three, maybe four of you, who go up a key, it seems. Do you know the bit I’m talking about?

Yeah, twice; we change key twice. [laughs]

It’s such an outstanding lift. That’s an amazing arrangement.

Are you talking about the one which turns into [sings] ‘Sharks are coming up to feed…’?

No, there’s another one earlier on where you all go “aaaaAAAHHH!” and all rise in unison on the word ‘love’, around three minutes in. It’s stunning.

Oh yeah, that’s right. [laughs] Very hard to do live, but full credit to Nick Launay for getting that version of that song down.

Now or Never Land, too, is another great harmony-heavy song. But I’m biased, Rob, because that’s the album that I grew up on, listening to you guys. It came out in 1993; I would have been five years old at that point, but I heard it a bunch more in my childhood and I still love it very much.

Well, that’s great to hear because it’s one of our favourites as well, and it took a long time to record. We watched seasons come and go while we were making that album, over at St Peter’s studio there [Megaphon Studios]. It was a funny one to put out there, because all the other bands a bit like us were becoming much harder and grungier at the time, and appearing at Lollapalooza. We were offered [to play at] Lollapalooza and we turned it down, of course, as we would. [laughs]

But just as bands were becoming more kick-you-in-the-guts, with big, fuzzy guitars and pounding, Dave Grohl-style drums and everything, we went the other way. We made a very harmony-based and melodic-sounding, and very varied album. But the test of time is always the thing, and now it’s the one that I go back to all the time as well, and really enjoy, now that the pain of recording has receded. [laughs] I can actually enjoy it at face value.

The five of you, plus everyone else in your camp, have essentially been keeping a terrible secret about Bones for some time…

Well, sorry to stop you there. I think Bones was actually keeping a terrible secret from us.

Oh, really?

Yeah. Without going into the details, we think that Bonesy knew something was wrong a long time ago, but being the amazing, independent Kiwi that he is, he didn’t want to burden that with anyone else. And his capacity throughout life to live an authentic life remained right until the end. And that’s why it appears to people that it happened really quickly, but in actual fact, I think Bonesy knew a lot longer, but didn’t burden even his nearest and dearest with it.

My gosh. I mean, that makes it even more devastating, I think, from my perspective and maybe from yours too, to not have known what he was going through.

Near the end, we knew that something was wrong. But we think he might have known for a lot longer.

When did you last speak to him, Rob?

I spoke to him about five days ago, and told him about friends and family, and just kept it light. I said, ‘Is there anything I can do for you, mate?’ and he said, ‘Yeah — you can come over here and mow my f..king lawn!’ [laughs heartily]

Living in Milwaukee, he loved his lawn; that was the highlight of his week, mowing it. The idea that his lawn might be untended was just too much to bear. [laughs] So he kept that funny, sharp edge right to the end, god bless him.

Even in happier and less dire times, did you have the kind of relationship with him where you could speak honestly and emotionally about how much he meant to you?

It’s incredible, you know, the outpouring of love about the guy from here and overseas, and people we haven’t heard from in years in years. It’s just been incredible. Old photos have come in of a very young Bones in New Zealand, and then he moved to Melbourne and was living with the Finns, and coming up here [to Sydney] to audition for our band, and then all those years with us, and then his time in Nashville. And then after the 2017 tour, ending up buying a place in Milwaukee.

It’s been a massive thing, and the main thing that everyone has said, as tributes pour in, is that the guy was really friendly, really funny, and really cared about people, and remembered people. But I’m getting a bit emotional, Andrew. I might leave it at that.

Thank you so much for time, Rob, and all the best to you.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout