Midnight Oil: The Hardest Line film captures band’s bold, larrikin activism

A new documentary film captures Midnight Oil’s 46 years of ‘stirring the possum’ through its bold activism, larrikin spirit, ‘commando events’ and hook-filled rock ‘n’ roll songwriting.

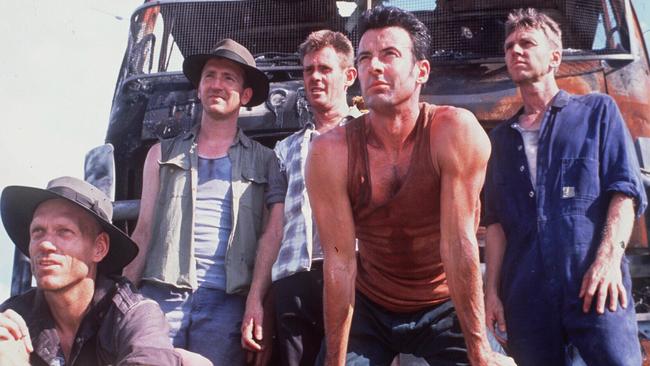

Rock ‘n’ roll bands are begun with an intoxicating cocktail sip that’s equal parts bravado, naivety, confidence and vulnerability. The recipe is as follows. Connect with other like-minded souls, usually while in the hormonal throes of adolescent insecurity; assemble your equipment, plug in, find your sound, then form an outward-facing circle and declare: it’s us against the rest.

Find success in a rock band and your reward is to play to bigger crowds who expect you to play the same old songs – even the ones you’re tired of, and which don’t reflect your present state of mind nor your accrued artistic expertise – while you’re trying your best to keep writing new numbers, often while you’re far from the stability and security of home.

Creative minds demand an outlet and as a generalisation, bands with multiple songwriters tend to do better in the long run: less pressure on a single individual, for starters, and a certain competitive friction can benefit all parties, as the better songs rise to the top while the lesser ones fall away – in theory, at least, depending on the willingness of the writer/s to play politics inside the rehearsal space, away from the public.

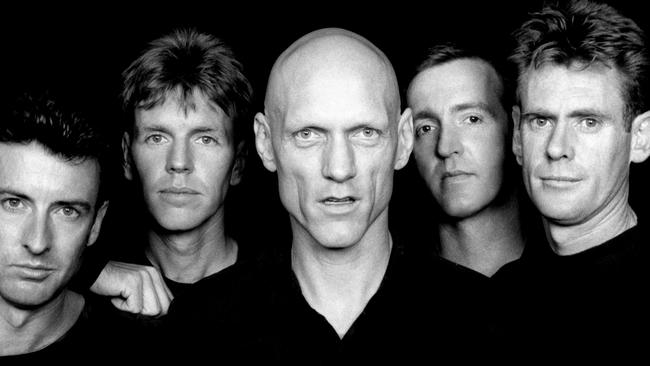

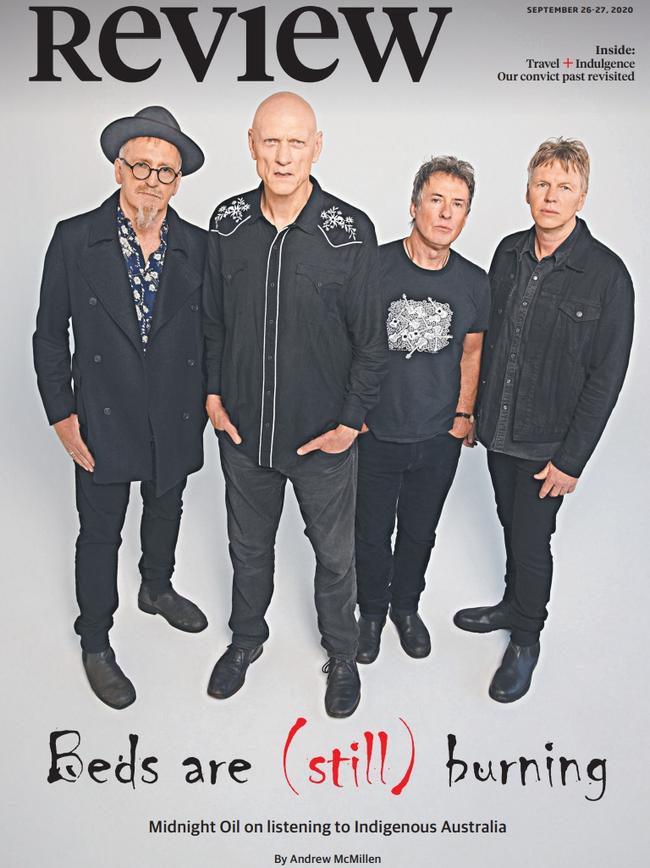

Sydney-born band Midnight Oil’s 46-year run is remarkable for a multitude of reasons, not least its sustained commercial success, collaborative songwriting nous and longevity. The band started playing under that name in 1976, disbanded in 2002, resumed touring in 2017, returned to the studio in 2019 and then ended in 2022 with a final world tour.

It’s a big story whose cast contains several large personalities who together achieved some high-profile moments that have lingered long in the nation’s collective memory. With its progressive-leaning politics and willingness to speak up and publicly support initiatives that have divided our population across the decades – environmentalism, Indigenous reconciliation and nuclear disarmament among them – the band has long been seen as a political animal, even though it issued plenty of nonpartisan songs on its 13 albums.

For his sins, accomplished filmmaker and behind-the-scenes Australian screen entertainment whiz Paul Clarke took up the challenge of squeezing its convoluted, contested, provocative history – and its place within the nation’s popular culture – into a 100-minute documentary film.

He eventually succeeded, and after a world premiere at the Sydney Film Festival earlier this month, the results will be in national cinema release from July 4.

Produced by Clarke’s company, Blink TV, and Beyond Entertainment, its principal funding was supplied by Screen Australia and the ABC in association with Screen NSW.

Blink and Beyond are coming off the back of a hit music film that went to No.1 with a bullet last year. Their documentary John Farnham: Finding the Voice – directed by Poppy Stockell, who co-wrote the script with Clarke – broke box office records to become the highest grossing Australian feature documentary of all time, and in February it was named best documentary at the AACTA Awards.

But this one is a tale that took Clarke seven years to finish – an unusually lengthy development for a music film release, and its long gestation is telling.

Another hint, too, lies in the subtitle of Midnight Oil: The Hardest Line, which has a double meaning. Firstly and most obviously, even to casual fans, it’s a memorable lyric from one of the band’s best-known songs, from 1982, whose chorus goes: “Oh, the power and the passion / Sometimes you’ve got to take the hardest line.”

As well, it’s a proposition on which the film’s entire premise hinges. The question posed by Clarke and his contributing writers, Andrew Stafford and Nick Carroll, is this: what if a rock ‘n’ roll band never compromised in its ethics and values?

What if the band instead chose the harder, more combative path at every turn while navigating its ascent in the music industry – a business that’s not exactly known for its cuddly, accommodating, reasonable and collaborative nature, particularly within the highly competitive major record label system of the 1980s?

It’s an intriguing idea, and one that could only be applied to this band, which sought not to play the typical game – get noticed, get signed, get popular and stay popular, no matter the cost – but to rewrite the rules while dragging both its fanbase and the music business along with it.

That is the thread that binds the film and drives its narrative.

“Ultimately, the hardest line is the life that they chose for themselves,” Clarke tells Review. “Every one of us compromises in our lives; we have to, that’s what’s required in a lifetime, both professionally and personally. Midnight Oil never compromised in 45 years, and that is an original story.”

“Where that took them, you can see how hard that was to live through,” he says. “But at other moments, where you have these heart-stopping moments of activism that are so brave, and so uplifting, and capture the world’s attention because they’re so ballsy – there’s nobody that ever did that, and I think The Hardest Line captures those moments where their courage was just phenomenal. They were fearless; totally fearless.”

Once the lights go down at Sydney’s State Theatre for the premiere on June 5, the vibe soon turns from celebratory to restless. Because it’s the opening night of the Sydney Film Festival, there are a half-dozen guest speakers front-loaded at the podium on stage, including the NSW arts minister John Graham and Sydney lord mayor Clover Moore.

After half an hour of these thanks-giving stakeholder speeches from politicians and SFF leaders alike, the 2000-strong crowd – mostly diehard fans who wanted to see the film at the first available opportunity – is openly heckling by reprising the full-throated OOOIIILLLS crowd call that was a constant feature at their concerts, up to and including the final gig at the Hordern Pavilion in October 2022.

These people came here to be rocked by the sight and sound of the band’s story on the big screen, not sit through a bunch of speeches. (“I could have watched the first half of the bloody Origin,” grumbles a bloke behind Review, referring to the rugby league match unfolding across town.)

Clarke is the final speaker; he’s apologetic, and he understands the punters’ frustration, but he also points out that films like this don’t get made without a huge amount of help, and he needs to thank some people and financiers.

But the filmmaker has an ace up his sleeve, and it’s this: in the centre of the stalls, unseen by most under the cover of darkness, members of Midnight Oil and their families were guided to their seats.

When Clarke announces the musicians’ arrival and asks them to stand up, the house lights flick on and a huge cheer goes up: the men behind the music are in the theatre, the tension has broken, and the mood staggers back toward celebratory as the writer-director wraps up his remarks with an Oils lyrical reference: “The time has come”.

Well, almost all of the musicians were in attendance: singer Peter Garrett, drummer Rob Hirst and guitarist Martin Rotsey all smiled and waved for the adoring crowd, but the other member of the original foursome was in absentia. (Three men played bass on its recordings; the longest-serving bassist, Bones Hillman, died of cancer in 2020, aged 62.)

“I haven’t run away to Ireland to get away from the whole thing,” Jim Moginie tells Review with a laugh. “I find it an intense experience to watch; it’s like your whole life flashing in front of your eyes. But I’ve seen it enough. It’s a good film, and it’s the whole story.”

The guitarist and keyboardist is in Ireland for a series of events tied to his recently published memoir, The Silver River; he also loves visiting the country he calls his “second home”, thanks to blood family ties he found there in midlife, having grown up in Australia as an adoptee, a fact he learned at age 11.

“In the film, you can tell we’re a bloody-minded bunch of bastards; we weren’t going to sit back and let the industry lord it over us,” says Moginie. “That kind of larrikin thing, that’s part of the band’s nature as well, that we weren’t going to put up with that. I think people liked that; they like to see people standing up to ‘the man’.”

“That really comes through in the film to me, this ‘hardest line’ idea: sometimes you’ve just got to go for it,” he says. “That’s your path, and you’re like an arrow that’s just going to shoot through where it goes. I think we always did that; it was in our nature that we were those sorts of people, really.”

Covering 45 or so years of interpersonal, international and musical history is a tall order for any filmmaker. This wasn’t the sort of band that was happy sticking to the usual write-record-promote-tour treadmill, either: those “heart-stopping moments of activism” Clarke mentioned earlier were occasional and unusual flashpoints for a rock band, and naturally enough, they became tent poles in the film’s narrative.

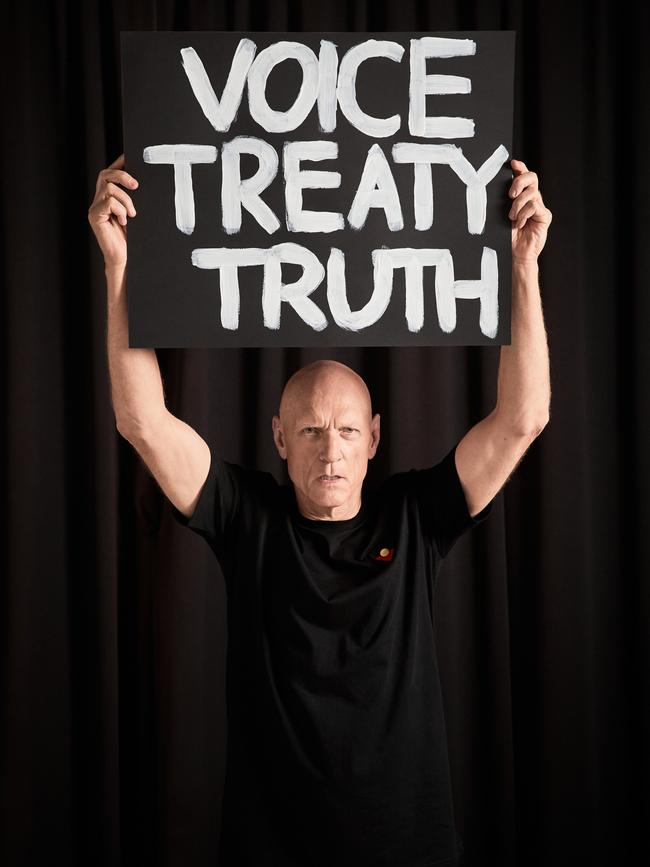

Several such moments are highlighted on screen, the biggest and best-known of which was the band’s political protest at the closing ceremony of the Sydney Olympic Games on October 1, 2000.

Unimpressed with prime minister John Howard’s steadfast unwillingness to apologise to Indigenous Australians for what had occurred on our shores since white settlement, including the Stolen Generations, the band hatched a secret plan to make a statement of its own. “It was a commando event, really,” Rotsey told this writer in 2020, in an oral history compiled to mark its 20th anniversary.

Shortly before they took to the stage at Stadium Australia to perform their signature song Beds Are Burning, the five members stripped off a top layer of clothing to reveal black overalls prominently displaying the word ‘SORRY’, in white capital letters, in an array of positions so that they’d be captured by the cameras at all angles for a global television audience estimated at one billion viewers.

Outside of the band’s inner circle, the only other individual aware of the plan was artistic director and producer David Atkins, who was sworn to secrecy, and appears in the film to confirm his advance knowledge.

That performance footage is owned by the International Olympic Committee, and perhaps unsurprisingly, licensing its reuse is “extremely expensive, but you’ve just got to have it; it’s one of their really triumphant moments,” says Clarke.

How costly? “I can’t tell you, but it’s a lot of money. They’re counting by the second. It’s more expensive than any other archive (footage) there. But it’s just necessary. You’ve just got to have it in there – and they know it,” he says with a laugh.

As these scenes unfold at the State Theatre during the premiere, the crowd erupts in cheers and applause for its greatest moment on the world stage, and a provocative statement for which the musicians will always be remembered.

It was the ultimate example of that larrikin spirit to which Moginie referred earlier, and entirely in fitting with the band’s character and reputation for “stirring the possum”, as Garrett might put it.

On screen, at the conclusion of the Olympic Games performance – as the applause subsides in the State Theatre almost 24 years after the event – a commentator wisely intones a few words that also work as a kind of artistic credo: “Midnight Oil – never afraid to make a statement.”

When Review suggests those few words are a fine summary of the band’s mission statement, Moginie replies, “It is, but not everybody liked it. You make the assumption now that people (thought), ‘Oh yeah, what a great event.’ But I have people coming up to me now going, ‘You guys are a bunch of wankers for doing that.’ Part of the story of the film was the fact that, if you are going to stick your neck out, at some point, someone’s going to try and bring you down a few notches.

“If you do take the hardest line, a lot of people aren’t going to like it,” he says. “You can never assume, even now – look at the way the (Indigenous voice) referendum went – that people are going to be on board with a message about Indigenous people. I mean, the country’s still got a long way to go.

“In a way, the band’s work isn’t done; I think Martin says in the film, ‘You can’t be silent’,” says Moginie. “If that’s another message from the film, then I think that comes through, too.” (In 2020, Moginie told this writer: “I think if Midnight Oil’s a thorn in the side of people, so be it. Great; let it be that.”)

Perhaps seeing and hearing this story on the big screen will help a new generation of artists and bands find their voice to speak up for what matters to them. “It really does show you what’s possible if you’re in a band and creating music with friends, where you can actually take it,” says Clarke. “That’s a really important takeaway of it. The chances of those people coming together, and what they decided to do? I love that. That stuff just really lights me up.”

But what’s brought home perhaps hardest of all in the film is its excellent soundtrack. Nobody knows better than the musicians themselves that their message wouldn’t have gone far beyond Sydney’s pub circuit if the music wasn’t shot through with clever melodic and lyrical hooks, stirring guitar lines, bass grooves and drum beats, all arranged within the familiar blueprint of rock ‘n’ roll.

“All we’d ever done was try to give people something authentic, writing about where we were from and what we cared about in the hope that it would resonate; to deliver more than just a rock show, where the setlist is laminated to the foldback wedges,” writes Moginie in the closing pages of his memoir, reflecting on its final tour, and on the giant footprints that he and his bandmates left behind.

Midnight Oil: The Hardest Line is in national cinema release from Thursday, July 4. The writer travelled to Sydney as a guest of Roadshow Films.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout