Nick Cave interview: music icon opens up about marriage and family tragedy

'That wasn’t in the game plan, to be the person that people look at with tears in their eyes,' says Cave, whose life changed dramatically in 2015. 'For me, it was never supposed to be that.'

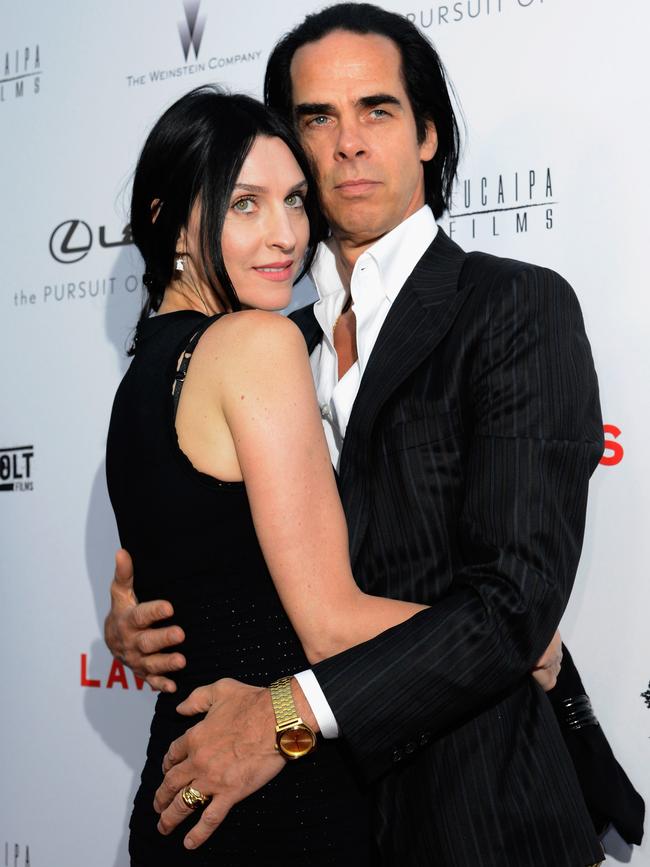

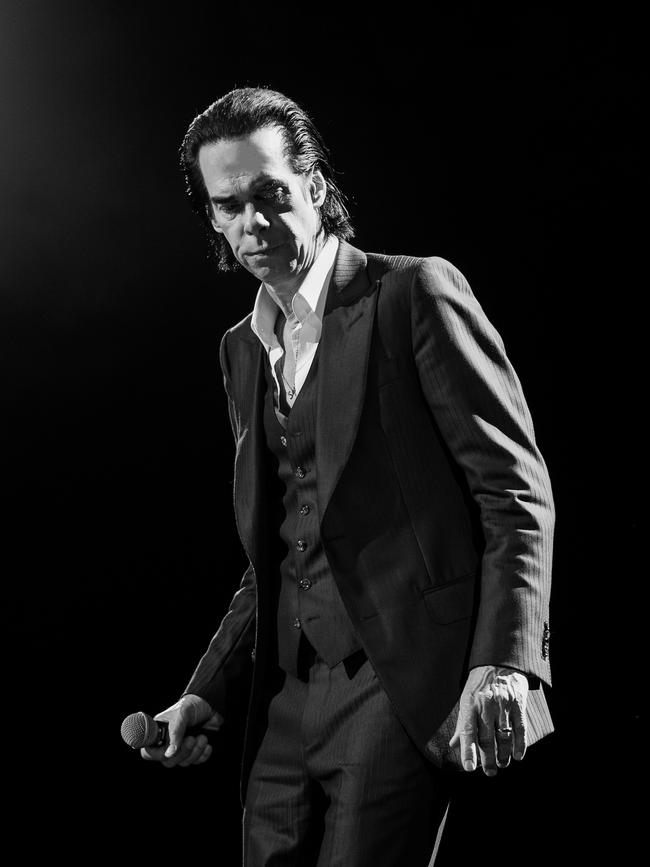

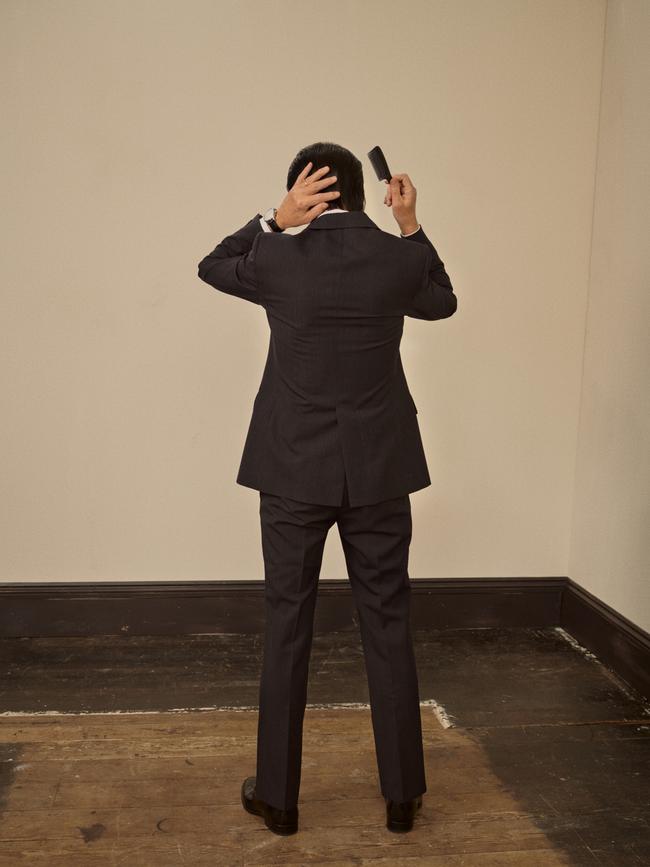

Nick Cave strides into the room wearing a dark blue pinstripe suit and a white dress shirt unbuttoned enough to show a silver chain carrying the name of his wife, Susie, against his bare skin. He offers a handshake greeting and sits down. Some stationery is set neatly before us on the table in the hotel meeting room and Cave jokes around with it. “This is really corporate!” he observes. “We can do note-taking.” He scrawls my name at the top of the page, underlines it and recaps the pen. A bit of pantomime from rock’s prince of darkness. A bit of role-reversal.

Ah, but this is my interview, Nick. We’re in Sydney where he and Susie have been staying during a stop on his series of solo concerts across Australia. The reason he and I are sitting in a hotel meeting room is to talk about Wild God, the upcoming 18th album from Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. The album departs from the usual practice of Cave and Warren Ellis producing; Cave confirms they invited legendary Mercury Rev and Flaming Lips sound engineer Dave Fridmann in for the mixing. I ask if the lyrics on Wild God came easily. Cave’s eyebrows arch toward his high, dyed-black hairline. He confesses to being nonplussed. “This is so weird, I’ve gotta say,” he says. “This is the first music interview I’ve done in years.”

I should know. I’ve been chasing him for an interview since I joined The Australian as music writer six years ago. Cave has spent these years talking a lot about such things as God and spirituality, grief, fashion and ceramics via outlets like Sean O’Hagan’s tremendous 2022 book Faith, Hope and Carnage and Chopper director Andrew Dominik’s acclaimed films, and even Cave’s own newsletter, The Red Hand Files. But something as quaint as a sit-down interview for a newspaper magazine about a fresh album? He hasn’t done that with any Australian music journalist since 2017.

So here we are. I want to know if he’s on board. “Are you into it?” I ask. “Oh, yeah,” the 66-year-old replies. “No, I’m happy. I mean, it’s just a weird situation. I just sort of sit there in interviews these days, and talk about our culture or whatever, so I’ve completely forgotten how to do a music interview. I’m very happy to talk about anything. Go for it. So what was the question?”

I have a few and as promised, Cave answers them openly. We dig some more into Wild God, where over 10 tracks his beloved Bad Seeds – Thomas Wydler, Martyn Casey, Jim Sclavunos, George Vjestica and Warren Ellis – pour themselves into their first traditional, full-band rock ‘n’ roll record in more than a decade. With strings and gospel choirs lending additional colour, these are stunning, dynamic songs, even if I suspect some may only reach their highest cruising altitude when played live.

Over two hours we talk about the music and a lot more besides, as Cave is so much more than a musician, songwriter and frontman now. He’s philosopher, cultural critic and spiritual adviser to a whole generation via The Red Hand Files. At one stage he apologises – “Sorry, you have to tidy all this up please… I haven’t had a lot of sleep” – although he is highly articulate and rarely delivers an incomplete sentence. He hardly moves in his seat, only raising his hand to take a sip of his coffee which sits mostly untouched. When he wants to strike from the record something ambiguously expressed, he makes a scissor-cutting gesture and his gold wedding band glints in the light. Mostly he faces the window, looking out on the grey clouds that hang above Sydney Harbour on this gloomy morning, caught in a slipstream of memories, although his blue eyes lock onto a direct gaze when he wants to emphasise something important. His face is a portrait of indifference except when he smiles or laughs, which is more often than you might think.

Once, in Cave’s early punk days perhaps, being interviewed in a five-star hotel would have been anathema given his reputation as an anarchic hell-raiser. But things change, and people change, too. If they survive long enough.

That Cave has made himself available to speak to The Weekend Australian Magazine came out of the blue. For a time it seemed he might never speak to the press again. “Interviews, in general, suck,” he opined in Faith, Hope and Carnage, which was composed of hours of conversations with his friend O’Hagan, an Irish journalist. “Really. They eat you up. I hate them… at some point, I just realised that doing that kind of interview was of no real benefit to me. It only ever took something away. I always had to recover a bit afterwards. It was like I had to go looking for myself again. So five or so years ago I just gave them up.”

It’s no coincidence that Cave’s retreat coincided with the worst thing in the world happening to him, an event that reshaped everything that would follow for Cave and his family.

One night at home in Brighton, England in July 2015, Cave was sitting on his couch, watching TV, when his phone lit up with a call from the phone of one of his 15-year-old twin sons, Arthur. Nick and Susie thought he was staying at a friend’s place, but the voice on the phone was not Arthur – it was a stranger who said he’d found the phone, a rucksack and shoes in a field near the black windmill outside Brighton.

The caller reported that there was police activity at the cliff near the windmill. What followed was a sudden rushing panic, a phone call to police begging for answers that didn’t come – and then detectives arrived at the family home wearing composed faces, masks carefully configured to impart bad news. Standing in the kitchen, the detectives delivered the most terrible answer for those unanswered questions: their boy Arthur had fallen off the cliff and died.

Cave’s head began roaring with an impossibly loud noise. Arthur’s twin brother, Earl, collapsed on the spot, and Susie caught him. Cave remembers arriving at the hospital, interminable waiting and confusion, and then being led into a makeshift annexe where Arthur’s body was laid out with a sheet over him. He remembers his son looking so calm and beautiful, with a clean white bandage. He looked so angelic.

Later, in a coronial inquest, they – and the rest of the world – learned that Arthur and his friend had secretly decided to try LSD for the first time, and that led Arthur to fall at the cliff, suffering a brain injury that killed him instantly. In recording a verdict of accidental death the coroner noted: “In his own family’s words: ‘He was a bright, shiny, funny, complex boy and we loved him deeply’.”

What we know now, but didn’t then, is that the tragedy would herald a metamorphosis. I asked Warren Ellis in 2022 whether it’s an oversimplification to divide Cave’s career into before and after Arthur’s death. Ellis, who was at Cave’s house when his dear friend and long-time collaborator got the call, and when the police arrived, replied, “I just think it’s a fact. I’ve always been amazed at how he and his family decided to work through it. It wouldn’t have surprised me if Nick said, ‘I don’t want to play live anymore’, or ‘I don’t want to do anything’. Who knows how you react in that situation? But I’ve found him and his family to be incredibly inspiring. I’m constantly inspired by the way they’ve navigated that terrible event.”

A year after Arthur’s death, Andrew Dominik released his documentary One More Time With Feeling, blending Bad Seeds studio performances of songs from Skeleton Tree with footage of Nick, Susie and Earl picking up the pieces of their lives in the wake of Arthur’s shocking death. Cave has said that he and Susie were like birds trapped “in an oil slick, incapable of moving” – until they watched the documentary. And the film freed them.

I ask Cave what the documentary means to him now. “I’m very happy it exists, but it’s not something that me and Susie sit under a lap rug and watch on Netflix,” he says, with a grim laugh. “But that was one step toward a kind of openness about things that was extremely helpful to me.”

He adds: “Look, this is such a complicated thing. But I think ultimately, if you’re a couple and something like this happens to you, if you can stay together half the battle is solved. Unfortunately, that doesn’t happen. It’s a terrible track record; I think 75 per cent of families break up over something like this. We haven’t done that.”

I ask about the silver necklace around his neck with Susie’s name engraved on it. “Junkie jewellery… there’s an area in New York where you buy that sort of stuff,” he says.

Cave was a heroin addict in 1997 when he met the then Susie Bick, a model who worked with fashion designer Vivienne Westwood, among others, and appeared on the cover of magazines like French Glamour and Elle. The pair were smitten, but Cave’s heroin habit was a problem, to put a heavy thing lightly.

His five previous attempts at quitting hadn’t worked, but the sixth one did: a moment of clarity, spurred by his love for Susie, put him on a plane to Arizona for a final rehab stint, which took. He’s been sober since. They married in 1999 and their twins, Arthur and Earl, were born in 2000. Cave had two other sons, both born in 1991: Luke, with his first wife Viviane Carneiro; and Jethro, with Lee-Anne “Beau” Lazenby. Jethro died in May 2022, aged 31, in a hotel room in Melbourne. The cause of death hasn’t been reported.

The Caves made remarkable creative leaps after that cataclysmic night in July 2015. Susie’s fashion label, The Vampire’s Wife (named after an unfinished novel by her husband), became a supercharged outlet for her grief. “She basically had a small company that didn’t really know what it was doing – and then Arthur died, and she just started making certain types of clothing,” Cave explains. “They were, in my opinion, just sort of manifestations of her situation … and were extraordinarily beautiful spiritual creations, and it just took off.”

Her Falconetti dress was named Dress of the Decade by Vogue, and its famous wearers included Princess Kate and Kate Moss.

“It’s part of the weird world that I live in, that I get sort of sucked into the slipstream of various things, almost accidentally – so I am sitting around, looking at dresses and checking if it should be a French seam on the bottom,” he says with a laugh. “Or a ‘baby lock’, which is a way of finishing a seam without having to fold it under, and all of this sort of stuff, making these sorts of decisions with Susie.”

But even as we spoke, the bell was tolling for The Vampire’s Wife. On May 27, three weeks after our interview, Susie announced the business was closing, following the collapse in March of one of the brand’s largest stockists.

Susie, of course, had been on the road with her husband weeks earlier, posting candid photos and videos on Instagram alongside red heart emojis – although the ex-model who appeared (nude) on the cover of the 2013 Bad Seeds album Push the Sky Away is absent in these images. Cave says Susie’s presence at his shows “sort of ups the ante to some degree, because she’s listening, and I love her, and I want her to be proud of what I’m doing”. A Bad Seeds show isn’t like any other Nick Cave concert. There’s sometimes no distance between Cave and the audience, who surround the band, and particularly Nick, with their worshipful watching. Susie stays close on these nights.

“She worries about the Bad Seeds shows; she’s pathologically concerned with everyone’s safety, and she sort of watches in terror.” At the final show of his tour, in Brisbane, Susie is there, hidden from our view but for her hand, extended beyond the curtain to record the crowd with her phone. “This is for my wife, who’s standing there. She’s filming. Always f..king filming,” he sighs comically, drawing laughs. “This is for you, darling.”

In June, Cave published a Red Hand Files post that reads as a kind of eulogy to The Vampire’s Wife: Susie’s dresses were an attempt to give her grief form by throwing fabric over an invisible boy, as an act of love, an act of mercy, and an act of contrition… From a small distance, over the ten years the company existed, I have watched in awe at the defiant, grief-soaked, joyful ambition of it all. Today, I feel nothing but pride.

The birds in the oil slick set free again. Or as Cave tells me, choosing his words carefully now: “Part of the tragic pleasure of this thing was watching Susie emerge in front of my eyes from a kind of hell into something really extraordinary. I’m not able to see what’s happened towards myself in the same way, but I can certainly see it in her. That’s been a source of huge inspiration and solace.”

In Dominik’s One More Time with Feeling Cave tells a story of visiting a local bakery in a veil of grief. Someone grabs him by the arm and says, “We are all with you, man.” It’s a memory of kindness but in a voiceover Cave asks himself: “When did you become an object of pity?”

Here in Sydney, I tell Cave I don’t think it was pity we felt. More sympathy and admiration for how he and his family came through the tragedy together.

“Well, initially, you bristle against simply the act of sympathy, you know; you don’t want to be ‘that person’,” Cave responds.

“That wasn’t in the game plan, to be the person that people look at with tears in their eyes. For me, it was never supposed to be that.”

But look at Jimmy Barnes, I say, whose 2016 autobiography Working Class Boy described in excruciating detail the harsh truths of his childhood soaked in poverty, violence, alcoholism and neglect. The brave literary act from the outwardly tough-as-nails Cold Chisel rocker unlocked the door for many readers to reckon with their own traumas. And what about how Cave’s audiences have responded with overwhelming positivity to his vulnerability, and how it has reframed how many regard him today, compared with a decade ago?

“Yeah, it feels like that,” says Cave, nodding. “Yeah, I understand that.”

And then – because this is a music interview – he adds: “I think I can just naturally go places with songs, or in a performance of a song, that I couldn’t go 10 years [ago]; I didn’t know how. Whatever way you put yourself back together, it’s different, and you have different capabilities. I’m just able to do things and deal with matters and be with people in a way that I never was before that.

“People mostly used to just piss me off, essentially – and that changed radically.”

Cave is very famous for a musician who has never had a mainstream No.1 hit song; his name, face and general moody vibe are familiar to most Australians over the age of 40 even if they can’t name much beyond the 1997 piano ballad Into My Arms or 1994’s Red Right Hand (the theme song for British crime drama series Peaky Blinders). Today, the Bad Seeds’ most popular song on Spotify is O Children, a 2004 deep cut that was later used as the soundtrack to a key scene in a Harry Potter film; it has 146 million streams. The closest he came to a pop hit was his 1995 duet with Kylie Minogue, Where the Wild Roses Grow (It debuted at No.2 on the ARIA chart.)

Born in Warracknabeal in 1957 and raised in Wangaratta, he moved to Melbourne in his early teens to study at Caulfield Grammar School. There he met musicians including Mick Harvey, who would become a crucial collaborator in their first band, the post-punk act The Boys Next Door – later renamed The Birthday Party – and then onto the enduring Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, which formed in 1983.

He and Susie, who is British, have lived in the artsy, seaside town of Brighton since the early 2000s – he told the local paper in 2015: “It wasn’t my idea to move here, it was my wife’s idea, and I just kind of followed her really”.

Cave has long been a polymath. Across four decades he has produced 18 albums with his main band and a few more with side projects including Grinderman and his double act with Ellis. He has written two novels, plus film scripts – John Hillcoat’s The Proposition (2005) and Lawless (2012) – and many screen scores, including The Road (2009) and Blonde (2022), both co-composed with Ellis. He has also curated art exhibitions and music festivals.

But three years after Arthur’s death, in September 2018, came an entirely new chapter. The Red Hand Files was a way for Cave to answer fan questions publicly – you could say that, like social media, it’s a means of staying in the public square without talking to journalists. There have now been more than 300 editions of The Red Hand Files, a publication at turns insightful, revealing, moving and witty (40-odd years of dark Gothic balladry cloaked in violent imagery notwithstanding, Cave can be devilishly funny).

There’s Cave on being mistaken for the actor Nicolas Cage, and a richly detailed encounter with British artist Bryan Ferry (a cautionary tale); the transformative experience of recording with his hero Johnny Cash, and this definitive answer to a question about why he attended the King’s Coronation as part of the Australian delegation last year: I am not a monarchist, nor am I a royalist, nor am I an ardent republican for that matter; what I am also not is so spectacularly incurious about the world and the way it works, so ideologically captured, so damn grouchy, as to refuse an invitation to what will more than likely be the most important historical event in the UK of our age. Not just the most important, but the strangest, the weirdest.

“I get maybe 500 or 600 letters in a week, and I read them all,” says Cave. “It’s a flow of people attempting to navigate great tragedies in their life… there’s other stuff, too, but the thread that runs through the whole thing is of people coping.

“It’s incredibly inspiring, and life-changing, to just have this thing that’s like a river of sorrow and strength running through my life. It’s been enormously helpful for me, and so the responses are very much inspired by that. And people find them helpful in return.”

Cave and Ellis’s tour of Australia in late 2022, their first after Covid lockdowns, seemed to crystallise Cave’s growing evolution, with a setlist that favoured the spectral, sparse and emotionally raw tracks from Ghosteen (2019) and Carnage (2021) – which were the first songs Cave had written after Arthur’s death. Female backing singers injected a gospel feel and Ellis’s penchant for synthesisers lent an electronic influence, resulting in surprisingly uplifting shows that held audiences aloft for two hours each night.

In the audience on the Canberra leg of that tour was music obsessive Anthony Albanese, who had been elected Prime Minister earlier in the year. Albanese’s Cave fandom dates back to watching The Birthday Party at a Sydney University gig when he was a student. In a 2015 interview for Jeremy Dylan’s My Favourite Album podcast, Albanese picked the 1990 Bad Seeds album The Good Son (which boasts Bad Seed signatures The Ship Song and The Weeping Song), reflecting a period when, he says, he was “completely obsessed” by Cave’s music.

Cave vividly recalls meeting Albanese at the 2022 Canberra gig. Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood was touring bassist. Albanese walked in, pointed at Greenwood and declared OK Computer (Radiohead’s seminal 1997 album) “one of the top three albums of all time – and mixed in with that, an unbelievable amount of expletives,” chuckles Cave.

Was having a Prime Minister at a Nick Cave concert a new experience? It has never happened in Britain, Cave confirms. “I think I’ve been there since Maggie Thatcher – she didn’t want to come. Boris [Johnson] never came,” he says, smiling.

Is it a Labor endorsement? No more than going to watch a coronation is an endorsement of a king. “I don’t spend much time focusing on Australian politics and what goes on; I don’t know the finer details of all of that, but [Albanese] was an extraordinarily personable and likeable character,” he says.

Cave adds that Albo is “a music guy. It felt like he just wanted to hang out with some musos”. All true, says the PM. “Oh, it’s so much different from hanging out with pollies,” Albanese tells The Weekend Australian Magazine. “For me, music and sport are two great escapes. When you’re at a gig – particularly one as captivating as a Nick Cave gig – you’re not thinking about productivity or growth; you’re not thinking about the latest issues that you inevitably have to deal with, that come across your desk. You’re just enjoying the moment, and you’re in that moment.”

During Cave’s Australian tour this year, Greenwood was on bass again. Albanese went one further and invited the pair to The Lodge the morning after their Canberra concert. “I gave him a bit of a tour and we had brekky and a chat,” says a delighted Albanese, 61. “He checked out the piano that’s there at The Lodge, and played a bit; it was a fairly surreal moment.”

Beyond the music, says Albanese, “I think he’s a really interesting guy, in the way that he responds to fans through The Red Hand Files, and engages with people. He’s obviously an artist in every sense of the word. He’s a poet. He’s a writer, a lyricist; someone who is an intellectual who’s interested in the state of the world… It’s one of the fantastic things about him: he continues to grow, and his music reflects things that have happened in his personal life, of course; the sad tragedy involved. Some of that can be quite dark, but I find the music uplifting. I love his voice, and I think he’s an extraordinary writer. So it’s been nice to get to know him a bit.”

Several years after pressing pause on “rock ‘n’ roll interviews”, as he calls them, why is Cave back, talking to me? “Because it feels new,” he says. And here’s something very new, late in our interview. “Have you checked out any of the AI stuff?” asks Cave. “Are you gonna throw this through ChatGPT? There’s a song generator thing called Suno, have you looked at that? It’s insane, and it’s deeply troubling.”

Cave says he asked Suno to create for him a dark, slow, gothic song about a banana. “And within 15 seconds it spat this song out called The Dying Peel,” he says. “It was good; it had a good chorus. It wasn’t great. It even understood that there’s a sort of joke going on about the dark gothic song on the banana, that you were taking the piss a little bit – and so The Dying Peel talks in all these extended metaphors about the blackening of the skin.”

Amazed, at least initially, Cave prompted Suno to write a death metal song about the Rape of Nanking – but by halfway through he’d lost interest, depressed and nauseated. “It’s frightening, but my manager is like, ‘It’s OK, because ultimately people will want the real thing.’ I’m not so sure about that.

I’m an enormously optimistic person about the world in general, but I just think the demoralising effect, or the humiliating effect that AI will have on us as a species will stop us caring about something like the artistic struggle.

That we will just accept what is fed to us through these things; that we’ll be in awe of the banal. That, to me, is the direction that it’s going.”

His concerns are on my mind the following week, when I watch the real thing on stage. Cave’s shows are intensely human. It’s there in his request that the people sitting upstairs “go f..king nuts” when he sings the word “balcony” in his 2021 song Balcony Man; the audience complies and Cave can’t help but crack a smile.

Could AI ever recreate Susie’s videos from Cave’s tour earlier this year? The thousands of people in thrall to her husband’s music, stories, his joy and sorrow, his furrowed brow and his grimace-like smile, his deathly serious demeanour and the cracks of light that splinter through occasionally, piercing the mood in a pattern of tension and release that has now become a calling card of his persona?

Tucked inside his jacket pocket on that tour were the unheard songs of Wild God that Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds will soon tour the world with – a European and UK run from September to November, and an Australian visit sometime next year. Arenas in France and Denmark. Two shows at The O2 in London.

“The unique thing about the Bad Seeds is it’s had this slow, barely visible, incremental rise to ‘stardom’. It just gets better in that respect,” says Cave. “Which, for a person of my age who’s been around and made as many records as I have, is completely counterintuitive. It’s not usually that way – or it is that way, but it’s predicated upon everyone coming along and hearing the ‘good old hits’ and that sort of stuff. It’s just not that for us.”

It was on stage in Sydney that Cave shared the news he had become a grandfather (take that, AI), after Luke’s wife gave birth to a boy days earlier. Congratulations, I say. Cave smiles and speaks of “joy”.

Joy is the name of the fourth track on Wild God, a piano ballad where Cave sings that he is visited by a “ghost in giant sneakers”: This “flaming boy said, ‘We’ve all had too much sorrow; now is the time for joy’.”

Days after his first grandchild was born, Cave wrote an entry in The Red Hand Files, which would soon pop into the inboxes of Cave fans around the world: I thought of my son, Luke, and his wife, Sasha, who had welcomed their own baby boy into the world last night, and I experienced a wave of great elation. A breeze rippled across the lawn, the birds cawed, the sun shone high in the sky, and the great gum trees seemed to burst from the ground – all for my own momentary enjoyment, for a new grandfather, sitting on a park bench, on this most happy day. A child is born and the world continues wildly upon its way.

Looking out of the window of our hotel meeting room he says that he now sees five male generations of his family, all in living memory: his grandfather, his father, himself, Luke, and now this newborn boy. “There’s something extraordinarily powerful about that to me,” he says. “I sort of feel, on some level, the reason why I had children in the first place was to become a grandparent.”

Cave is brand new to this caper, but he’s got some ideas about what the role entails. “A grandparent is an extraordinarily free individual. It’s not someone that has to worry too much… you can just be that mad old grandfather – I love the idea of it – who just sits and says what they think,” Cave laughs and adds, “and the father is putting their hands over the ears of the young child. I know that from my own grandfather: just this strange presence, completely out of time. I’m very excited to become that person.”

I invoke the character-led songwriting in his new album and Cave’s answer to my initial question about the lyrics in the work, which has as its central image a “wild god”. Cave explains that he is “this man with long, trailing hair, flying around, just looking at things and appearing and walking in and out of songs.” Like the grandfather from another time. Or the rock star who pops into our inboxes whenever he opens his laptop and clicks onto The Red Hand Files and feels the tug of the river of sorrow that runs through many of the questions sent his way by people searching for hope and answers.

It’s a heavy thing to carry around, but it’s a responsibility Cave takes seriously, because when everything turned black in 2015 it was everyday and ordinary kindness that helped resuscitate him to a life in full colour, so that he could be of service to his fans, from the Prime Minister to the guy in his local bakery. We are all with you, man.

Wild God is released on August 30 via PIAS.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout