The ‘secret, terrible beauty’ Nick Cave teaches us about grief in new book with Sean O’Hagan

Australian singer-songwriter Nick Cave hates doing interviews. With the help of Irish writer Sean O’Hagan, he has created a new way of communicating his innermost thoughts in a new book.

The woman standing behind the counter at the grocery store had served Nick Cave many times. The pair were friendly, in the sense of shared pleasantries between a worker and a frequent customer who liked seeing and speaking with each other, but this visit to Infinity Foods was different.

Since the last time he had stepped into the business in search of vegetarian takeaway food, Cave had experienced a monumental tragedy. His 15-year-old son, Arthur, had died in an accidental cliff fall that made international headlines. Naturally, in the British seaside city of Brighton where they lived, the news was inescapable.

This ordinary day was the first time Cave had gone out in public since Arthur’s death. His skin crawled with the body shock of grief, and as the Australian singer-songwriter stood in the queue at Infinity, the friendly woman behind the counter asked him what he wanted to eat.

The whole interaction felt a little strange, because there was no acknowledgment of anything out of the ordinary; instead, she treated him just like anyone else, matter-of-factly, professionally.

As she handed Cave his food selection and his change, the woman briefly squeezed his hand, purposefully. It was a quiet act of kindness, and one that brings him to tears when he recalls it in conversation. It was the simplest and most articulate of gestures, from one human to another in a time of great suffering.

To Cave, the hand-squeeze meant more to him than all that anybody had tried to tell him in the time that had passed since his world was up-ended. Language sometimes fails us in the face of catastrophe, yet without a word, this woman had shown her customer that she wished the best for him.

“I’ll never forget that,” he says. “In difficult times I often go back to that feeling she gave me. Human beings are remarkable, really. Such nuanced, subtle creatures.”

Stillness was what Cave craved in grief, yet perversely, stillness became a scarce commodity. Instead, he was filled with an internal chaos: a roaring, physical feeling combined with a sense of dread and impending doom.

While lying awake in bed next to his wife, Susie, he felt as though the despair was bursting through the tips of his fingers. In desperation, he reached across and took Susie’s hand, only to feel the shock of that same violent electricity in her fingers.

We tend to think of grief as an emotional state, but what is less often spoken about is its physical effect: an atrocious, destabilising assault on the body that is unrelenting.

Cave had practised meditation for years, but following Arthur’s sudden death in July 2015, he thought he could never do it again. The notion of sitting still and allowing those feelings of grief to take hold of him would be a form of torture and impossible to endure.

At one point, though, he forced himself to go upstairs, sit on Arthur’s bed, and try. It was there, during that meditation while surrounded by his dead son’s belongings, that Cave felt the first, briefest moment of stillness.

“I had this awareness that things could somehow be all right,” he says. “It was like a small pulse of momentary light and then all the torment came rushing back. It was a sign and a significant shift.”

Years later, Cave and his closest collaborator, the Ballarat-born multi-instrumentalist Warren Ellis, began writing new songs. Their lyrics addressed Arthur’s absence both directly and indirectly, in the sense that the loss of his son is a condition, not a theme, and as such it infuses everything.

The songs appeared on an album by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds titled Ghosteen, a work that was completed in secret ahead of the band leader’s last visit to Australia, when he performed several concerts of his film music with Ellis and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in August 2019.

Whenever Cave visited Melbourne, he would stay at his mum’s unit in Elsternwick, 9km southeast of the city centre, with Susie and their twin boys, Arthur and Earl. This habit was set in stone: Susie was fond of saying that her husband had taken her to Australia 20 times, but they’d never gotten out of Elsternwick. (“She definitely has a point,” he admits.)

Dawn Cave attended her son’s concerts whenever he performed in Melbourne, all the way through his career. She had always taken a keen interest in his creative expression, and so when the 93-year-old asked to hear Ghosteen a couple of months ahead of its release in October 2019, her son naturally obliged.

With Ellis, he had done all the initial recordings for these songs at a studio that overlooked Arthur’s grave, in a field beside St Wulfran’s Church in Ovingdean, the next town along from Brighton. Spectral, haunting and often without a traditional rhythm section in its arrangements, it is a work far removed from the usual rock ’n’ roll energy summoned and captured on a Bad Seeds album.

“She sat in her wicker chair in the kitchen and listened to it all the way through,” he says. “She was visibly moved – so visibly that I was concerned about her response and asked her if she was OK. She said, ‘This is a very sad record, darling, but a very beautiful one’.

“Now, the thing was, over the next few weeks, while I was living there with her, I would walk into the kitchen and she would be sitting in her chair listening to it, lost to it, really moved,” he continues. “It was as if it was speaking to her, not just about Arthur, whose death hurt her very deeply, but all the many people a woman of 93 has inevitably lost. And, at that age, that’s essentially everybody.”

After his concerts at Hamer Hall, Cave returned to London. His last memory of his mother is of her standing at the door of her unit, hunched over her walking frame, waving goodbye. Between them was the unspoken sorrow that this may be the last time they would see each other in person, and it was: she died in September 2020, and the pandemic meant that he could not be there for her.

“Interviews, in general, suck,” says Cave. “Really. They eat you up. I hate them. The whole premise is so demeaning: you have a new album out, or a new film to promote, or a book to sell. After a while, you just get worn away by your own story.

“I guess, at some point, I just realised that doing that kind of interview was of no real benefit to me,” he says. “It only ever took something away. I always had to recover a bit afterwards. It was like I had to go looking for myself again. So five or so years ago I just gave them up.”

One of the last journalists to speak with Cave in a traditional press interview was this newspaper’s former music writer, Iain Shedden, for a Review cover story published in early 2017, ahead of the Bad Seeds’ national tour in support of its 16th album Skeleton Tree.

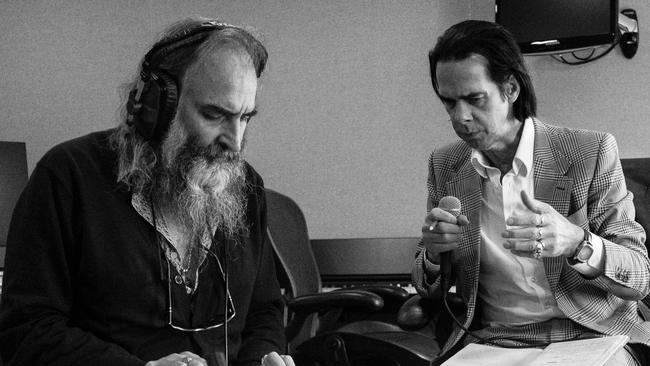

So if the man tends to shun interviews, how do we know the particulars of the scenes described above? They all appear in a beguiling, resonant book by the Irish writer Sean O’Hagan, who began speaking with Cave by phone mid-pandemic, in August 2020.

Their conversations usually lasted a couple of hours, sometimes stretching to twice that length, and the resulting book is most unusual in that it’s published entirely in a Q&A format, across 15 chapters comprising nearly 280 pages.

Titled Faith, Hope and Carnage, it was authored by both men, although not written in theusual sense of the word. Instead, through their casual, friendly and at times emotionally fraught conversations – followed by careful, judicious transcription and editing – Cave and his faithful interlocutor O’Hagan have chiselled an all-time literary masterpiece from rough granite.

The book offers many things to a casual reader, and anyone familiar with the artist’s hefty body of work will find much to savour, as there’s plenty of rich, detailed and self-effacing discussion of his creative process and various working relationships across the decades. But perhaps above all else, it forms a guidebook for navigating bereavement and re-engagement with the world following the death of a loved one.

“To be forced to grieve publicly, I had to find a means of articulating what had happened,” says Cave in the third chapter. “Finding the language became, for me, the way out. There is a great deficit in the language around grief. It’s not something we are practised at as a society, because it is too hard to talk about and, more importantly, it’s too hard to listen to. So many grieving people just remain silent, trapped in their own secret thoughts, trapped in their own minds, with their only form of company being the dead themselves.”

A master of the English language, Cave cannot help but try to find words to explain and describe the ineffable. Time and again he has stood up to the challenge, and with each successive public offering – Skeleton Tree, then Ghosteen; his 2021 album with Ellis, titled Carnage; his email newsletter The Red Hand Files; three films and several concert tours – he has extended his, and our, understanding of the darkest nights of the human soul.

Faith, Hope and Carnage is the newest contribution to that body of work, and it is a wonder. From Cave speaking with O’Hagan – across more than 40 hours of sparkling, searching conversation in all sorts of moods, and at different times of day and night – we come to understand him and his manner of thinking in three dimensions, as it were, rather than via the cardboard cut-out version that is often the best that writers such as myself can offer from an interview conducted during a press cycle promoting a particular project.

Poignantly, the book was completed before another shock loss befell the singer: Cave’s oldest son, Jethro Lazenby, was found dead in a Melbourne motel earlier this year, aged in his early 30s. “Many others have written to me about Jethro, sending condolences and kind words,” Cave wrote in The Red Hand Files on May 24. “These letters are a great source of comfort and I’d like to thank all of you for your support.”

Towards the end of the book, he shares with O’Hagan a letter from a fan in Fremantle named Tiffany, who writes of the recent loss of her 22-year-old son from an overdose. She asks him how he and Susie dealt with the trauma of losing Arthur, and she shares a brutally evocative poem about the night her son died.

“Grief is not just an amorphous fog-like state of being,” Cave says to O’Hagan as they discuss the poem. “Grief actively revolves around a point of torture, a moment of realisation, an actual tangible thing. Tiffany dared to step into that moment, unprotected, with eyes wide open, and write it down. When I read it, it moved me to tears – as many of the letters do – because of the sheer openness of it, and, God, I don’t know, the bravery. The power of her poem made it safe to turn around and face my own point of trauma.”

The conversation about Tiffany’s letter seems to trigger something in Cave, and in the next chapter, he tells O’Hagan that he was moved to phone one of his closest friends, Warren Ellis, who was at the family home in Brighton the night Arthur died. “Are you sure you even want to talk about this stuff?” asks O’Hagan, cautiously. “F..k, I don’t know, Sean,” Cave replies. “But after talking to Warren, I’m just kind of mystified by how little I remember, just how much I have forgotten. Like, the day Arthur died just rears up out of nothing …”

And he goes on to recount his jumbled memories of the sequence of events: a horrifying call from Arthur’s phone made by a stranger who had found his son’s device in a field near a cliff; soon after, the police detectives with composed faces standing in their kitchen, telling them the news; his head immediately starting to roar “the loudest noise in the world”; Arthur’s twin, Earl, collapsing, and Susie catching him instinctively; the escalating confusion, the sudden horror …

“There is a lot of hesitancy around this because it feels invasive, but the bereaved need encouragement to speak sometimes,” says Cave, a few pages later. “They are prone to silence because they’re worried about the effect their sadness will have on other people. And this silence becomes habitual, but also builds up like a terrible pressure. Anyway, Warren was always there. We just didn’t talk about it much. Neither of us had worked out how to do that.”

Crucially, it’s worth noting that it took him more than five years to ask one of his closest friends about that night and the aftermath, where Cave tried to work through the pain. Three months later, the Bad Seeds were in a studio outside Paris, trying to complete an album that felt haunted with imagery that, in hindsight, appeared to portend Arthur’s death.

“It felt like I was walking through treacle, or walking against the wind,” he tells O’Hagan. “Throughout the entire Skeleton Tree session I just felt dead, but I knew if I didn’t do the record then, I never would. In retrospect, I was clearly in no condition to be there at all. … In the end, Warren pushed that record through.”

There are no deadlines when it comes to grief; each person responds differently. Few would have faulted Cave if he had shut up and shut down the entire subject forevermore.

Instead, despite the paradox of being a private person who lives his life in public, the singer-songwriter has decided to open himself up in such a way that there are now few things he won’t openly discuss. As a result, he has become a messenger of an experience that’s as commonplace as love, yet much less often spoken about.

“Since Arthur died I have been able to step beyond the full force of the grief and experience a kind of joy that is entirely new to me,” he says. “It was as if the experience of grief enlarged my heart in some way. I have experienced periods of happiness more than I have ever felt before, even though it was the most devastating thing ever to happen to me.”

“This is Arthur’s gift to me, one of the many,” he says. “It is his munificence that’s made me a different person. Susie, too. We’ve never felt more engaged in things. I say all this with huge caution and a million caveats, but I also say it because there are those who think there is no way back from the catastrophic event. That they will never laugh again. But there is, and they will.”

In response to a fan question in the Red Hand Files in October 2018, he wrote, “Dread grief trails bright phantoms in its wake.” That perfect sentence contains multitudes of great magnitude, and within its eight words it captures the deep vein of pain and beauty that he and Ellis, in particular, have been mining since the day that Cave’s world caved in.

Arthur’s death became a motivating force, and many of the meaningful things that he has felt and shared, both publicly and privately, in the past seven years all lead back to that moment like a powder trail.

That is the secret, terrible beauty at the heart of loss, which Cave – arguably one of the world’s great thinkers, speakers and writers – has so eloquently written here in these pages, with O’Hagan’s gentle, empathic assistance. Of course he would give it all back if he could see Arthur again, but those cosmic deals are not to be made.

This book is another bright phantom trailed in his wake. The wind is at his back, now, as he strides forward, carrying this mighty gift, unimaginably changed.

Faith, Hope and Carnage is published on Tuesday, September 20 by Text Publishing.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout