Blossoming of a Bad Seed

How did Warren Ellis, from working-class Ballarat, end up a revered central figure in Australian music?

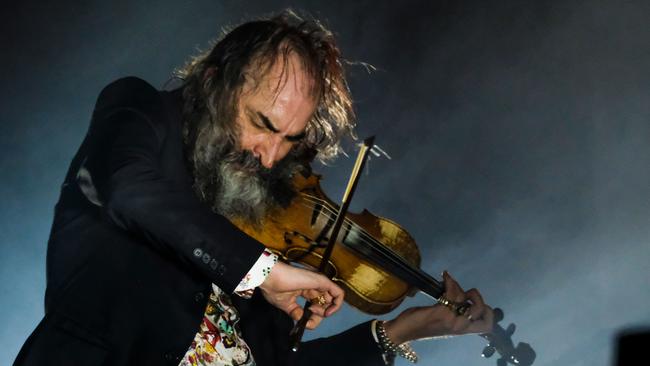

With his curved back to the crowd and his leather shoes earthed in a power stance, the bearded and besuited man faces the bass drum and saws away. His amplified instrument has a guitar pickup attached to it, and when he steps on a distortion pedal, the room fills with the hair-raising, rarely heard sound of a violin feeding back into the amplifier.

Rock ’n’ roll history is littered with the familiar sights of players bent over guitars or ecstatically windmilling their strumming arm, with the image of wide-mouthed singers grasping microphones, with livewire drummers thrashing away at their kit, and even with saxophonists leaning into deep notes.

That’s all been par for the course for more than five decades but what Warren Ellis has offered since the early 1990s is a new silhouette, a new shape that had never been seen in this context. A new approach, in effect, just as this instrumental trio discovered when it first began playing together for beer money in the corner of a pub in Melbourne under the name Dirty Three.

Guitarist Mick Turner stands to the side, concentrating; the tall man barely moves, his expression impassive, mind on the music. Most of the time Turner watches drummer Jim White while the pair hold down the rhythmical beds of long, wordless songs, where Ellis’s bow on strings drives the melody.

It’s a Sunday afternoon in mid-June at Hobart’s Odeon Theatre, and the group is performing the first of two sold-out performances of its 1994 self-titled debut album as part of the Dark Mofo festival. On record, its seven tracks run for 49 minutes, but on both occasions the trio’s time on stage reaches two hours thanks to Ellis’s fondness for colourful, fantastical anecdotes to introduce each song, their preference for intuitively extending each arrangement as long as deemed necessary and generally revelling in the life-affirming glory of a rare Dirty Three concert.

A few weeks earlier the band performed at the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall as part of Vivid Live festival — its first live performance anywhere on the planet in about three years, a booking that only came about at the request of Robert Smith, the singer and guitarist of British gothic rock band The Cure, which headlined the festival.

Inside the Odeon, Dirty Three follows the course of its first of eight studio albums, which flits between barn-burning rock ’n’ roll maelstroms and quieter, meditative numbers, including one where Ellis takes a seat to play a piano accordion in Odd Couple. That’s just about the only moment where he’s stationary, as much of the rest of the set sees him attacking the art of live performance like a man possessed.

From walking on stage and leading a crowd-wide singalong to the Boz Scaggs hit Lido Shuffle, to lying on his back with his legs flailing like a gassed cockroach during Sue’s Last Ride in the encore, Ellis pulls focus with each high kick and every guttural howl he directs towards the ceiling.

He abuses his instrument in a way that would make classical players blanch. He hands his violin to audience members for them to hold aloft like a holy artefact for a few moments; he tosses his bow over his shoulder to punctuate a song’s abrupt end. He stands with his back to the audience, arms spread — and with all eyes on him, lit by a spotlight, he hocks and spits a loogie off to the side of stage, towards a spit bucket he had placed there earlier.

All of this is utterly compelling but one of the most extraordinary scenes occurs early on, when the band gradually reduces its volume to a whisper so that Ellis can lead the audience to sing a three-note melody during album opener Indian Love Song.

Time seems to stand still as the violinist conducts the crowd to repeat the simple, ascending phrase. As goosebumps prickle the skin of the hundreds stood before him, he leans into the microphone and says: “Once more for an old man from Ballarat.”

■ ■ ■

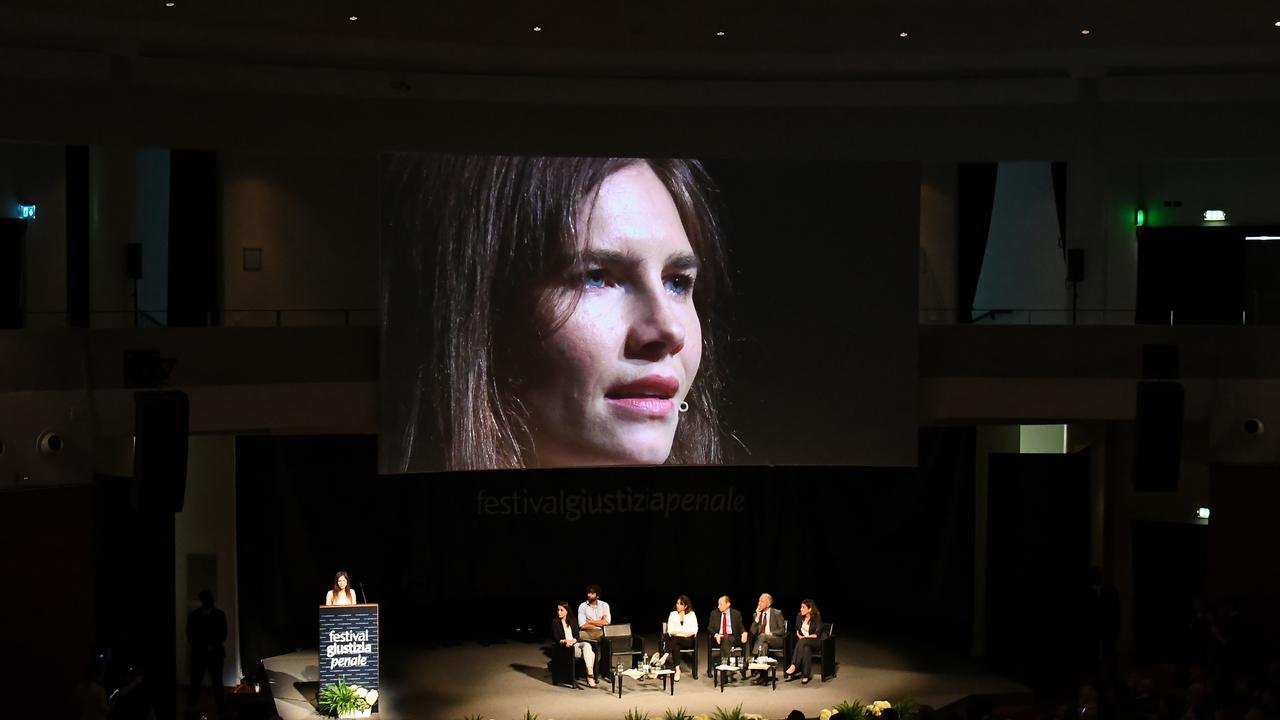

At Brisbane’s City Hall in January, about 1600 people gathered to watch Nick Cave at an experimental “in conversation” event, where the eternally black-clad figure alternately prowled the stage while pondering responses to fan questions and sat at the piano to perform songs as the mood struck him.

About 20 minutes into a marathon event that extended past three hours, the singer-songwriter from rural Victoria was asked: If you could choose one person dead or alive to collaborate with, that you haven’t yet, who would it be and why? He initially demurred by jokingly suggesting someone like Elvis, but Cave said he knew that such a pairing would do The King a massive disservice, as the whole thing would be less than it could have been if Elvis had done it on his own.

“So that’s the problem with collaborations, really,” Cave continued. “You have to find someone that, when we come together, it actually creates something that’s beyond the two of you. So collaborators I work with now, say, Warren Ellis, for example — who we all adore, because he’s so adorable — it’s a perfect collaboration, in the sense that, first of all, we remain friends.

“This is the problem with collaborations in general, I would say. They are such intense work situations that you do forget to stay friends, and I think the Bad Seeds in some ways are testament to being a powerful collaboration, and forgetting to be friends.

“You can’t really look at the Bad Seeds, in a way, without seeing the absence of a lot of members of the Bad Seeds, and that is, I think, because of both the creative and destructive power of collaboration. But me and Warren have a particularly special thing that’s going on. We’re very, very careful about the collaborative process, to remain very good friends.”

■ ■ ■

Music was a serious matter in the Ellis family home. His father was a newspaper printer mechanic who wrote and sang country and western songs, his mother loved classical music, and both parents encouraged their children to play instruments as they knew the beauty and the value of a life enriched by song.

It worked. When Warren found a piano accordion at the local rubbish dump, he took it to school, where a teacher showed him how to play it. That experience led to picking up the violin at the age of 10. He stuck with it and showed enough skill to win a scholarship to study music in Melbourne, which lifted him out of working-class Ballarat and on to the world’s stage, first with Dirty Three and then with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds.

In a dim, red-lit room adjoining the artists’ bar at a hotel in central Hobart, Review sits down with Ellis over a pot of Earl Grey tea. He wears a dark two-piece suit, a collared shirt that shows off his chest hair, a golden bracelet that rattles against his wristwatch and several chunky rings on his fingers, as well as sunglasses clasped around his neck despite it being night-time.

Combined with the long hair and greying bushman’s beard, his shaggy pirate aesthetic is as perfect an embodiment of Billy Connolly’s desired state of appearing “windswept and interesting” as it may be possible for a human to achieve. At once elegant and dishevelled, it’s a look guaranteed to turn heads.

“It’s like putting on a uniform,” he says with a shrug. “When you get dressed up to go to a wedding or a funeral, it’s such a great feeling. So why not make that every day?”

Since 1998, Ellis has lived in Paris with his wife, Delphine Ciampi. The following year he quit using drugs and alcohol. When asked about the role that sobriety has played in his life in the past two decades, he replies: “Without that, I wouldn’t have had the life that I’ve had. It’s really the only way forward for me, and it’s served its purpose: a lot of what I’ve done just wouldn’t have been possible, because, a) I doubt I would have been around and, b) I wouldn’t have been able to do it. I owe everything to that.”

Ellis and his wife have two sons, Roscoe and Jackson, who are both studying at university. Next month the old man from Ballarat will clock up 20,000 days on Earth.

His year so far has been perhaps his most productive to date. With Dirty Three, he celebrated the 25th anniversary of its first album with three glorious concerts, and also returned to the studio with his bandmates, which may result in the group releasing its first new music since 2012. He also attended premieres for two films he scored: Mystify: Michael Hutchence in Melbourne and in Helsinki for This Train I Ride, a documentary about American women who travel cross-country on rails.

Last but not least, the 17th Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds album, Ghosteen, was announced late last month in Cave’s email newsletter, a week before its surprise release. “I hardly breathed a word to anybody about it,” says Ellis, unable to hide his glee at keeping under wraps a project he had been working on since February last year.

At 54, Ellis is more energised and inspired by music than he ever has been. “It’s awesome being middle-aged,” he says, elbows on the table while leaning over the teacup sat before him. “I’ve been blessed to cross paths with some really great musicians. I’ve been fortunate that my path led me to people who bring this thing out in me, too. That’s not something that happens just sitting there.

“If you can stay in something long enough, and grow with it, it actually gets wilder, because you avail yourself to more things, because you have to,” he says. “There’s things that I couldn’t have done 20 years ago, because I wasn’t ready for them — and you’re not meant to be, I don’t think.”

■ ■ ■

Ellis joined Cave’s band as a session violinist in 1994, around the recording of eighth album Let Love In and its ensuing tour. Since then the Bad Seed from Ballarat has become not just a fixture of a group formed in 1983 but a songwriter and composer whose name is now afforded equal billing with the band’s founder.

The first original film score they worked on together was for John Hillcoat’s The Proposition in 2005, and since then they’ve scored both indie films and Hollywood features, including The Road (2009), West of Memphis (2014) and Wind River (2017), as well as the National Geographic television series Mars (2016).

In August the pair premiered an event with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, where a selection of these works was performed live for the first time, with footage from the films shown on screens behind the two composers, the orchestra and conductor Benjamin Northey.

“An unforgettable evening,” wrote The Australian’s critic, Patrick Emery, after seeing one of four sold-out concerts at Hamer Hall, and more than a month after those shows Ellis is still powerfully moved by how it all came together.

“I’d never done anything like that ever before,” he tells Review by phone in late September while striding around Brighton, England, having helped his 19-year-old son move on to a university campus. “I mean, I played with orchestras when I was younger but nothing like that. And then on top of that, to actually have an orchestra playing our compositions — I didn’t really know what to expect because there were so many unknowns about it.

“It was very dreamlike and surreal, and I could tell by the look on Nick’s face, he was experiencing what I was experiencing. It was so otherworldly and unexpected. It was just glorious. I’ve never felt anything quite like it, actually.”

■ ■ ■

When the idea of performing the first Dirty Three album was suggested to him, the violinist was reluctant as he’s generally not much interested in self-reflection or nostalgia. Instead, his eyes and ears are trained on works unwritten and unrecorded in the firm belief that his best music is ahead of him.

Yet as soon as the trio began playing together for the first time in three years, before a packed Sydney Opera House concert hall in May, Ellis was pleased to discover those 25-year-old songs felt as vital as they ever had.

While still mulling over the offer at the beginning of this most productive year, though, Ellis was invited to attend a solo theatre performance titled Raoul, which tells the story of a man without beginning or end. A decade after its debut, French actor and acrobat James Thierree had announced his intention to conclude the work, as it had become too physically demanding on his 45-year-old body.

“He’s the closest thing I’ve ever experienced to a genius,” says Ellis. “I saw the last show, and it was mind-blowing. I knew he’d been in an ice bath for a couple of hours beforehand. I saw him after and he was just absolutely drenched in sweat. I said, ‘So, you’re going to retire this?’ And he looked at me, and he goes, ‘You know, I keep saying it — but I want to see what I can do with Raoul when I’m 75’.

“And when he said that, I thought, OK, that’s a much better way to look at this: can I do this at 54? What will we sound like when I’m 75?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout