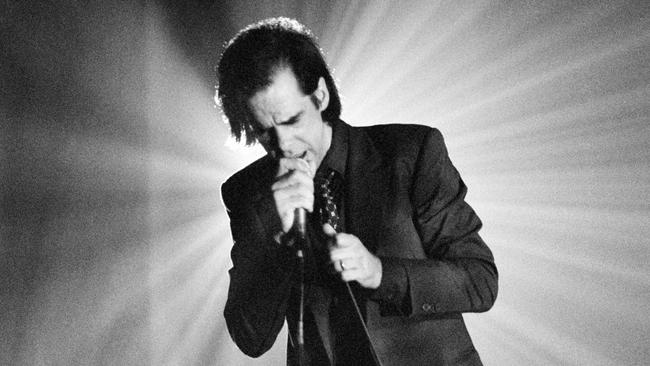

‘The struggle with the notion of the divine is at the heart of my creativity’: Nick Cave

He’d wake in hotels surrounded by the detritus of drugs, sex — and a Gideon’s Bible. Now rock’s bad seed opens up on his conservative beliefs and lifelong religious yearning: ‘I was operating in a Godless world.’

What is the driving force behind Nick Cave’s creativity? Journalist Seán O’Hagan recorded more than 40 hours of intimate conversations with the Australian singer-songwriter for their book Faith, Hope and Carnage. Here he asks Cave about his lifelong religious yearning.

Could we jump in and talk about things of the spirit, generally? Where would you like to start?

Well, once when I described your later songs as “spiritual”, in terms of their form and subject matter, you immediately countered with the word “religious”. I thought that was revealing. The word “spirituality” is a little amorphous for my taste. It can mean almost anything, whereas the word “religious” is just more specific, perhaps even conservative, has a little more to do with tradition.

Because religion requires a deep commitment and makes specific demands on the believer? Religion is spirituality with rigour, I guess, and, yes, it makes demands on us. For me, it involves some wrestling with the idea of faith – that seam of doubt that runs through most credible religions. It’s that struggle with the notion of the divine that is at the heart of my creativity.

Maybe we can explore that later. But are you saying, in terms of your faith and beliefs, you are essentially a conservative? Yes, that’s always been the case, and not just in terms of my faith. I think temperamentally I’m conservative.

That’s quite a loaded word. Well, it’s loaded for you, maybe.

Definitely. But do you mean you’re a traditionalist? OK, traditionalist, if you prefer that word. I’m not really that interested in the more esoteric ideas of spirituality. I’m drawn to traditional Christian ideas. I’m particularly fascinated with the Bible and in particular the life of Christ. It has been a powerful influence on my work one way or another from the start.

And yet it is little discussed when critics write about your work. Do journalists tend to shy away from the subject? Oh God, yes! For sure. I remember an interview with some music paper about 30 years ago, where the journalist sat down and said, “Before we even begin, I’ve been told by my editor, ‘Don’t get him started on God!’”

Does this interest in the traditional aspects of religion date back to your childhood? There’s certainly an element of nostalgia to it, I admit, and that probably goes back to the time when I first heard those Bible stories. I attended church a couple of times a week when I was young, because I was in the cathedral choir. And I learnt a lot by going to church. I became familiar with, and really loved, the stories of the Bible. I was just drawn to the whole thing. I remember buying a little wooden cross from the cathedral gift shop, with a silver Jesus on it, you know, to wear around my neck. I was around 11 years old. There was a piece of paper attached that said, “Made from the wood of the True Cross.” I thought, “Wow, the True Cross.”

Ah, they were lying to you, even then! Ha! Yes. And I asked my mother, “Mum, is this made of the actual cross that Jesus died on?” And she said, “Maybe, darling,” in such a way that I knew it wasn’t, but it still somehow retained its mystery. The point being, I always had a predisposition towards these sorts of things. And, later, when I became interested in art, it was often certain religious works that I turned to, above all. I felt they possessed a kind of supplemental power, beyond the art itself. That was a doorway, too.

So, back in your wilder days, when you drew on biblical imagery in your songwriting, was that also a reflection of a deeper interest in the divine? Well, I was surrounded by people who displayed zero interest in spiritual or religious matters – or if they did, it was because they were fiercely anti-religious. I was operating in a Godless world, so there was no nurturing of these ideas. But I was always struggling with the notion of God and simultaneously feeling a need to believe in something.

I have to say that was not always immediately apparent. No, I guess not! But I think people just saw what they wanted to see. I mean, those early Birthday Party shows were religious in their way, with all that rolling around on stage and purging of demons and speaking in tongues. It was old time, God-bothering religion! Or at the very least, preoccupied with religious matters. But, of course, I also had a huge appetite for mayhem. My life was extremely chaotic, and my music was, too, of course, but I was always trying to find some kind of spiritual home. Perhaps the chaos was one of the reasons for my underlying yearning for some deeper, more substantial meaning, but I don’t know for sure. The idea that there was no God or no such thing as the divine – no spiritual mysteries to speak of, nothing beyond what the rational world could offer us – was too difficult for me to accept.

So did you see religion as a way to give your life a degree of order? No, I don’t think that’s right. I had a major taste for havoc – but I had other things going on, too. I might wake in my hotel room surrounded by the detritus of a heavy night on the road – empty bottles, drug paraphernalia, maybe a stranger in my bed, all that kind of shit, but also an opened copy of the Gideons Bible with passages underlined. It was forever that way.

Back then, I assumed the Bible was simply a source of inspiration for your songs in much the same way that you were drawn to writers like William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor and the Southern Gothic tradition. Well, a big part of the attraction of those writers was that they were also wrestling with religious ideas. And the Bible is an incredible source of imagery and bold, instructive human drama. Just the language itself is extraordinary. I think there was always a yearning within me for something else, something beyond myself, from which I felt excluded. Even in the most chaotic times, when I was struggling with addiction, I always felt desirous of those who had a religious dimension to their lives. I had a kind of spiritual envy, a longing for belief in the face of the impossibility of belief that addressed a fundamental emptiness inside me. There was always a yearning.

I sense that you are actively attending to that yearning now. Well, yes, mainly because as I’ve gotten older, I have come to see that maybe the search is the religious experience. Maybe that is what is essentially important, despite the absurdity of it. Perhaps God is the search itself.

But doubt is still a part of your belief system? Doubt is an energy, for sure, and perhaps I’ll never be the person who completely surrenders to the idea of God, but increasingly I think maybe I could be, or rather that I was that person all along.

It’s intrinsically human to doubt, though, don’t you think? Yes, I do. And the rigid, self-righteous certainty of some religious people – and some atheists, for that matter – is something I find disagreeable. The hubris of it; the sanctimoniousness. It leaves me cold. The more overtly unshakeable someone’s beliefs are, the more diminished they seem to become, because they have stopped questioning, and the not-questioning can sometimes be accompanied by an attitude of moral superiority. The belligerent dogmatism of the current cultural moment is a case in point. A bit of humility wouldn’t go astray.

So, just to make sure I’ve got this right: you would like to get past your doubt and just believe wholeheartedly in God, but your rational self is telling you otherwise. Well, my rational self seems less assured these days, less confident. Things happen in your life, terrible things, great obliterating events, where the need for spiritual consolation can be immense, and your sense of what is rational is less coherent and can suddenly find itself on very shaky ground. We are supposed to put our faith in the rational world, yet when the world stops making sense, perhaps your need for some greater meaning can override reason… I think of late I’ve grown increasingly impatient with my own scepticism; it feels obtuse and counterproductive, something that’s simply standing in the way of a better-lived life. I feel it would be good for me to get beyond it. I think I’d be happier if I stopped window-shopping and just stepped through the door.

I’d say, be careful what you wish for; certitude is seldom good for creativity. I guess not, but who says creativity is the be-all and end-all? Who says that our accomplishments are the only true measure of what is important in our lives? Perhaps there are other lives worth living, other ways of being in the world.

Have you considered doing something other than writing songs and performing? I think it is more that you arrive at a point where the reason for making art, making music, changes. You find that it can serve another purpose entirely. You come to understand that this wayward energy you’ve always had, directed in the right way, can actually help people. That music can draw people out of their suffering, even if it is just temporary respite.

So you don’t see music as simply an escape? No, it’s more than that. I think music has the ability to penetrate all the f..ked-up ways we have learned to cope with this world – all the prejudices and affiliations and agendas and defences that basically amount to a kind of layered suffering – and get at the thing that lies below and is essential to us all, that is pure, that is good. The sacred essence. I think music, out of all that we can do, at least artistically, is the great indicator that something else is going on, something unexplained, because it allows us to experience genuine moments of transcendence.But to answer your original question: right now, I’m not considering doing something else; I love what I do and value my relationship with my audience. But what I was trying to say is that we may ultimately find that, to our surprise, our creative endeavours are not the defining element of our lives. They are perhaps a means to an end.

Have you considered what that end might be, for you? That’s what I’m trying to find out.

Edited extract from Faith, Hope and Carnage by Nick Cave and Sean O’Hagan (Text Publishing, $45)