Jimmy Barnes on pain, shame, guilt, letting it all go... and his new album

The boy born James Dixon Swan opened the door to his troubled life in a way never before seen by an Australian musician. It hasn’t been without consequences.

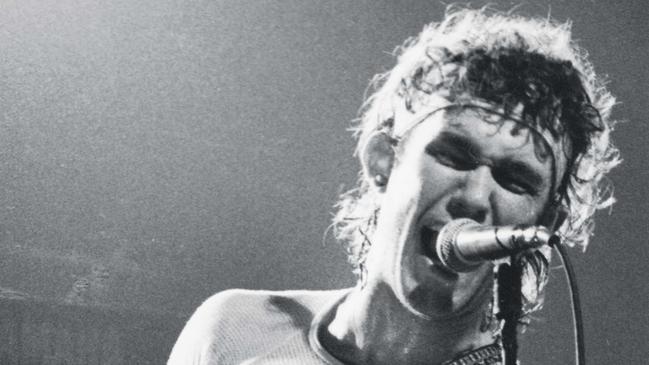

Jimmy Barnes is clearing his throat. Harrumph! he says, the noise coming from deep inside his chest. Harrumph! He frowns and gazes into the middle distance, focusing on his instrument and preparing it for what is to come. And in one fluid motion he clenches his fists, leans back, closes his eyes and opens his mouth. Heeeeyyyyyyy! Heeeyyyyyyyyy! The walls reverberate at the sound of pure, unadulterated Barnes, a man whose volume knob has the uncanny ability to flip from zero to 100 decibels in the blink of an eye. What’s going on inside that muscular throat of his is a minor miracle of human anatomy.

Try this at home: yell Heeeeeeeyyyy! as loud as you can. If you are a mere mortal, there’s every chance your voice will kink out at the top of your range and you’ll involuntarily cough at the sudden exertion. Jimmy Barnes, however, has been doing this to warm up before every show since the early 1970s, when the childhood choirboy first grasped the microphone in rock’n’roll bands in South Australia. More combine harvester than lawnmower, this warm-up routine comes on strong and sudden, like a lightning bolt igniting a dead tree from out of the clear blue sky.

That voice is one of the seven wonders of Australian music, up there with the three-chord flourish of Beds Are Burning and the bagpipe solo in You’re The Voice. Barnes jokes that it’s like a Mack truck: hard to start, but once it gets going nothing can stop it. On YouTube, there’s a 10-hour video loop of Barnes screaming that has attracted 1.4 million views. It’s a sound that could wake a cadaver, which is why it makes perfect sense that you can buy a Barnes-branded screaming alarm clock from his website if you have a spare $45 and the desire to wake in fright each morning.

Heeeeyyyyyy! he screams in his dressing room, causing his wife and daughter — who have their backs to him — to visibly flinch. Heeeeeyyyyyyy! he yells while stomping from his dressing room towards the waiting crowd, drawing surprised stares from nearby bar staff digging into icy tubs. Heeeeeeyyyyyyyyy! he projects while walking up the stairs to the stage, prompting roadies young and old to scuttle out of his way.

His face is fixed into a scowl as he prepares his voice, and when combined with the clenched fists, Barnes gives the impression of a boxer pumping himself up to pummel an opponent to within an inch of his life. Those days of hand-to-hand combat are well and truly behind him, though. Today, his bark is more potent than his bite. His fuse has lengthened as he has entered his seventh decade of life, though not without plenty of hard work in the underrated business of self-examination.

Seven songs into a high-energy set at a touring festival named Red Hot Summer north of Brisbane in early February, he pauses to address the crowd. “We’ve been playing a lot in the last few years, and I figured I’ve got to make some new songs, ’cause I’m sick of singing the same old shit,” he says. “So I’ve got a new record coming out, it’s called My Criminal Record. It’s a long record.”

Then his band — which includes his son Jackie on drums, his son-in-law Ben Rodgers on guitar, his wife Jane and his daughters Eliza-Jane and Elly-May on back-up vocals — begins a song that opens with a few stalled piano notes before moving into a slinky bassline and nervous percussion.

This is the first time most of the thousands in attendance have heard the title track to his forthcoming album, but unlike the hit singles he performs elsewhere in his set, this one has shrunk the distance between art and artist. This time, the man he’s singing about is the man who’s singing.

Well, I came from a broken home, my mama had a broken heart

And even though she tried to fight it, it was broken from the start

My daddy had a problem, but he always seemed to find himself a drink

When he finally hit rock bottom, we didn’t know how low he’d sink

For anyone who has read Barnes’s two best-selling memoirs, these declarations aren’t revelatory. What’s remarkable is how he has managed to find light in the dark days of his upbringing, where poverty and violence shared beds with alcoholism and abuse. On the page, these were the plot points of a tough life in which, for the boy born James Dixon Swan, the notion of dying before he became a man sounded like a happier outcome.

Tonight, in the context of a sparkling live concert, they become exclamation points. Far from wallowing in self-pity, the opening track from his 17th solo album exhibits the hard-won fruits of one of the toughest performers in Australian music embracing his past without fear or shame. As the band boils toward its chorus, Barnes sings a melody that explores the breadth of his considerable range:

My family has a record that’s as long as your arm

And I don’t want you to read it ’cause it’s going to do us harm

I keep it locked away somewhere I know, in a cellar that I call my youth

It’s my criminal record; it’s the truth

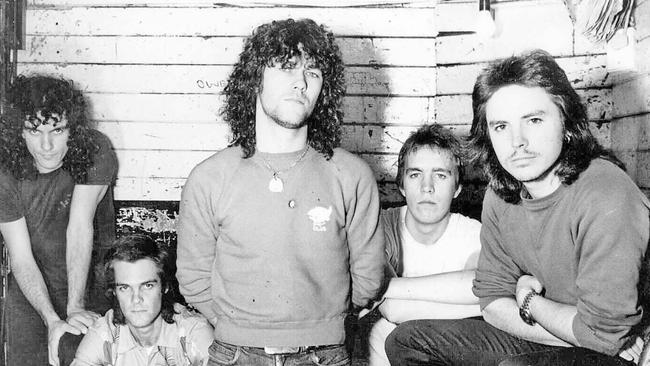

More than four decades after he left Adelaide in a van with his Cold Chisel bandmates — they were seeking a few interstate gigs and instead became one of the most popular and enduring Australian rock bands of all time — Barnes is in the midst of a prolific purple patch. Away from his established stomping grounds of concert stage and recording studios, he has set alight the film and book industries, too.

While the vocal warm-up remains the same, almost everything else about him has changed. Even for those paying close attention in the past three years, that change has been remarkably sudden. The revelations of his past found a ready audience: after the publication of his memoir Working Class Boy in 2016 came its second volume, Working Class Man, the following year. Their combined sales are approaching 500,000 copies, and both titles were named biography of the year at the Australian Book Industry Awards.

Then last year, director Mark Joffe’s film adaption of the first book hit screens nationwide where it set a record for the biggest box office returns for an Australian documentary, earning nearly $500,000 on its opening weekend and attracting 1.14 million viewers when it was screened on free-to-air TV. With these three projects combined, Barnes has opened the door to the cavernous room of his life in a way never before seen by a popular Australian musician.

The abridged version of his story is this: after emigrating from Scotland to Adelaide as a five-year-old in 1962, he and his siblings suffered at the hands of a violent father whose alcoholism kept the family locked in the grip of poverty and hunger for years on end. His mother fled the troubled home, leaving her six kids to fend for themselves until she found a decent bloke named Reg Barnes, who became the stable father figure they all so desperately needed. The young James Swan changed his surname to reflect the long overdue love, respect and tenderness that Barnes offered to the family, but those vital early years had warped the boy’s psychology in such a way that by the time he entered adolescence, he’d been hardened by a corrosive mix of self-loathing, disrespect for authority and a hair-trigger for violence. As he observed in Working Class Boy: “In reality I was afraid of anyone who might be smarter or better than me.”

From this dismal upbringing emerged a singular rock’n’roll frontman whose one and only happy place was on stage before a crowd, microphone in hand, anaesthetised by one or more psychoactive substances.

His musical longevity inspires respect from many of his peers, even from those who don’t necessarily travel in the same circles. When asked which artists they admire, for instance, Adelaide hip-hop group Hilltop Hoods immediately mention his name. “I genuinely respect that dude’s hustle,” says Dan Smith aka MC Pressure. “I’m impressed by his stamina. How has that guy been going that hard, that long? He tours like a beast, and he’s an amazing performer.” Smith’s high opinion is fitting given that Barnes is one of very few artists in ARIA chart history to have earned more No 1 albums than Hilltop Hoods.

Barnes has welcomed us to survey the contents of his life, good and bad. He has invited judgment of the behaviours and choices that have guided him into unhealthy patterns and situations. He has offered himself up to us wholesale, apparently without qualification or much in the way of censorship. Long viewed as one of the blokiest blokes in the nation’s popular culture, he has abandoned the stoic, unreflective approach to life shared by many peers from his era and instead spent nearly a decade in therapy, asking himself questions about his fundamentals as a human being. Who am I? What am I afraid of? How did the events of my boyhood shape me as a man? And what — if anything — can I do to unlearn those lessons and reshape myself into a better, kinder person?

“It wasn’t premeditated, it wasn’t a ‘career move’ — it was something I had to do for myself,” says Barnes in his dressing room at the Bribie Island show, as he unceremoniously drops his dacks to change out of his white jeans. “And people came along with it because they could tell that it wasn’t calculated. I just did it because it was the right time to do it for me, and I think it has opened up a lot of avenues for me.

“Internalising all that emotion and writing about it has given me much easier access to it now,” he says, pulling on his stage uniform of black jeans and black T-shirt. “I realise the stuff that I wrote about in those books, I’ve been using the same fears, the same guilt, the same shame, the same pain, the same love — for every night I’ve sung since I was f..king 14, you know? Only now, I know how to tap it. I’ve got more control, and I think I’m singing better because of it: it’s something I can harness, rather than be led by it. It’s a really big step forward — something you should learn by the time you’re 60,” he says with a laugh, bending to tie the laces of his enormous black boots.

Red Hot Summer promoter Duane McDonald reckons he’s done about 150 shows with Barnes since 2009, and reflects for a moment on what he’s noticed about the singer during the decade they’ve worked together. “I just thought he was a wild bastard; he was always wired differently,” says McDonald. “But no one knew all this shit had gone on in his life, except him. Now he’s got it off his chest, and it’s good to see him so healthy — and happy.”

Beneath a mirror on a table in his dressing room sit two unopened bottles: one vodka, one single malt scotch. They share some history, these bottles and Barnes. Alcohol has been a companion for much of his life, and he went on to develop a destructive habit. “I couldn’t stop getting smashed, I liked it too much, because when I wasn’t smashed I had to live with myself, this bloke I had been running from since I was a small child,” he writes in Working Class Man. “If I didn’t like myself as a kid, who had done nothing wrong, how was I going to live with myself as an adult, whose every step was one giant leap into self-loathing?”

When asked about the vodka and whisky, Barnes replies: “They’re for the band’s rider; they put them in my room. Nowadays, I never drink before or during the shows. I drink honey and hot water,” he says with a grin. “It’s really good.”

As the clock ticks towards showtime the door to his dressing room squeaks open: it’s one of his back-up-singing daughters, asking for her Dad to pass her a half-drunk bottle of beer. “See, the rest of the family never stop drinking,” he says while handing it over. Her return quip is barbed: “None of us were serious alcoholics,” she replies, and father and daughter share a hearty laugh about something that once ruled his life and came very close to destroying it.

Even though he now hits the stage sober, his body still vibrates with the sense memory of alcohol and amphetamines coursing through his system in the moments before the lights go down. But the average rock concert is child’s play compared to what Barnes has toured nationally in recent years: two stage shows talking about his life, and more subdued musical performances in support of his two books. It demanded a new kind of focus and stamina. “After the first shows, we got a lot of feedback saying, ‘This is my childhood’, or ‘This was my dad’s childhood’ — it was all too familiar,’’ says Mahalia, his eldest daughter with Jane. “In the second show, we had a few who were quite confronted because there wasn’t someone else to blame, it was his own alcoholism and drug addiction, insecurities and mental health issues. He wasn’t a bystander, a child, a victim — he was the perpetrator.”

Naturally enough, retelling the worst moments of his life for about three hours each night began to take its toll on Barnes. “Every night he got off that stage, he was completely wrecked,” says Mahalia. “With the rock shows, when he’s got nothing left physically, the adrenalin always kicks in. But after the emotional exhaustion of going through those stories and owning that, he really had nothing left every night.”

How did his children respond to seeing him backstage in that sort of state? “I’d tell him he did an amazing job, congratulate him and give him the support he might need,” says Mahalia. “It’s a really big effort and it is exhausting to hear it — let alone being in it. When it’s been your life and the cause of so much heartache for yourself, to relive that is a full-on experience.”

Son Jackie’s response in those moments was more hands-on. “We used to just have a hug, tell each other we loved each other, and talk about the show,” says the drummer and pianist. “The way I’ve been brought up by dad is to put the same into every show. Friends of mine who had seen those shows, I’ve talked to them about suicide and depression. It really has opened up a lot more conversations. So many people come up to me and say, ‘Tell your dad — thank you for helping.’”

Songwriter Don Walker knew something was up a few years back when Barnes asked to meet him for coffee, because that’s not the sort of thing his longtime Cold Chisel bandmate usually does. When they got together, Barnes brought a recorder with him to capture their conversation. He wanted to pick Walker’s brain about a few of the foggier memories of their shared history. “That’s when I knew he was doing something really different,” says Walker. “One of the things that was quickly apparent to a lot of people in the writing world with the first book was, ‘Holy shit, this guy can write!’ People were looking around under the carpet for a ghostwriter. There’s not, because I saw him tapping it out, and I read some extracts at the laptop phase. And when I read the writing, it’s unquestionably his voice. It’s stream-of-consciousness Jim. But a lot of it is a lot easier to read if you weren’t there, and a lot more entertaining. For me, I look at every chapter heading and go, ‘Oh, no. F..k, do I really want to go there again?’”

Their songwriting partnership endures; Walker had a hand in about half of the songs that appear on My Criminal Record. Both of them mention that another Cold Chisel album is in the works. “He has an extraordinary and quite unique voice,” says Walker. “He’s also done a lot of work in his youth in perfecting the craft, and working out exactly what he wants to do and doesn’t want to do.

“I’ll give you a little example,” Walker continues. “Crooners like Sinatra, they treat a melody like a saxophone would treat a melody. In any particular note, in whatever melody you’re going past, a crooner or a tenor player will allow themselves the leeway to zoom up to that, or down to it, or play around with it and be flexible with it. And the same with vibrato, and a whole lot of other tools that they have in the scabbard. Jim has all those tools, but he’s very Protestant about the way he uses them. As an act of discipline, if there’s a note there that has to be hit, part of Jim’s craft is that he hits it bang-on, from the beginning of the note. He doesn’t have to, he can do what the crooners do — but as an active choice, he hits it like a nailgun, and he stays there for a disciplined length of time, and then it’s off. The note is on and off. Sometimes he’ll use the other tools sparingly, but it’s part of his craft to enhance his impact, to work in that way.”

That is as finely tuned an observation about the quality of Barnes’s voice as one can find. Is this the sort of thing the two of them have ever directly discussed? Walker laughs. “No, we don’t talk about this stuff,” he says. “Only girls talk about this stuff.”

A question about how therapy has changed Barnes is met with another laugh. “Jim is cleverer and more charming and more manipulative than any therapist that’s been born,” says Walker. “He doesn’t talk to me about it, and I don’t ask him about the therapy side of things. When I found out that he was seeing a therapist from a third person, I exhibited no curiosity. All that side of Jim’s life, I leave to him. It’s just not part of our relationship. We have a much deeper relationship than that: we write songs together.”

When Bruce Springsteen toured Australia in 2013, Barnes was his support act at Hanging Rock, the outdoor venue north of Melbourne. Before the show, the American rock great summoned the Australian singer to his dressing room and asked if he’d like to perform a song together. Barnes nominated Tougher Than the Rest, the second track from Springsteen’s 1987 album Tunnel of Love.

Well, there’s another dance, all you’ve got to do is say yes, the pair sang. If you’re rough and ready for love, honey, I’m tougher than the rest.

That song has long held special significance for Barnes, as it was released when he was in the midst of his worst period of alcohol and drug abuse, and was pushing his wife Jane away as a result. Yet at parties, he’d turn it up and sing its powerful words directly at her, using The Boss’s lyrics as a plea for her to stick with him. And she has, through thick and thin, good times and bad: 38 years and counting. His cover of that song is the final track on My Criminal Record, and it’s intended as a declaration of devotion to the woman whose name is tattooed on his chest.

They’re not so different, Barnes and The Boss. Both have ruled the charts, airwaves and arenas of their respective countries while mining distinctive veins of rock’n’roll anthems aimed squarely at the ears of working class men and women. At 63, the Australian is six years younger than the American, yet both have published books in recent years that closely examine their pasts to better understand their respective presents.

Last December, Springsteen completed a run of 236 solo shows at a theatre in New York City, where he interposed songs with stories, just as Barnes has done in recent years. With Jane by his side, the pair travelled to see one of those Broadway shows, and when he played Tougher Than the Rest they held hands and shed a tear as The Boss sang: The road is dark, and it’s a thin, thin line / But I want you to know, I’ll walk it for you any time…

Near the end of Working Class Boy , describing the time just before Cold Chisel left Adelaide, Barnes wrote: “I learned that the public and the press don’t need to know everything about you or they might turn on you.” The past few years of his life, then, might be seen as a kind of conscious unlearning that hinges on his decision to shine a bright light into the dark corners of his life’s closet, skeletons and all.

At the Red Hot Summer gig, looking out at the hill full of happy punters belting out every word of favourite tracks such as Khe Sanh and Lay Down Your Guns, it’s unclear how many of them would have an interest in cracking the spine of either book. Yet it’s difficult to imagine any reader willing to invest the time in 800-odd pages of Barnes’s heartfelt prose walking away from that experience with less respect for the man himself.

His band hits the final notes of a powerhouse 90-minute performance and Barnes is the first to leave the stage. While the house lights are turned up and the crowd begins filtering out, he strides back to his dressing room, beaming and soaked in sweat. After delivering a show like that, his younger self would have little on his mind but the self-obliteration offered by those two unopened bottles. But he is no longer that man. Tonight, he’s the designated driver.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout