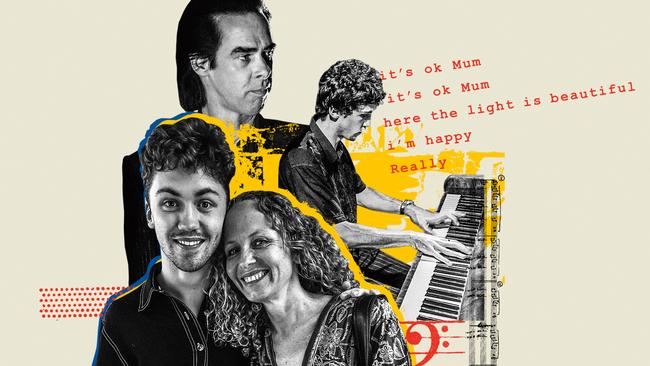

Tiffany Barton’s words of grief reached Nick Cave and became his inspiration

Devastated after losing her talented son, Tiffany Barton reached out to another grieving parent, the musician Nick Cave. What happened next was magical | LISTEN

We played Philip Glass as they lowered my son’s coffin into the ground. It was his favourite opera. My daughter was wailing as the celebrant read the words that we found in one of his notebooks. “My love for you is higher than the heavens, deeper than Hades and broader than the Earth. Everything must have an ending, except my love for you.” He’d copied it from Glass’s Einstein on the Beach.

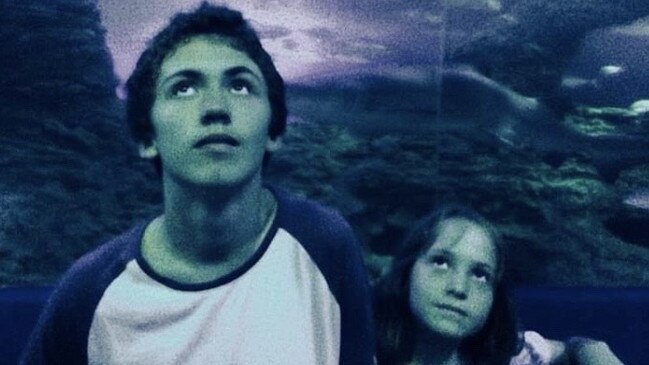

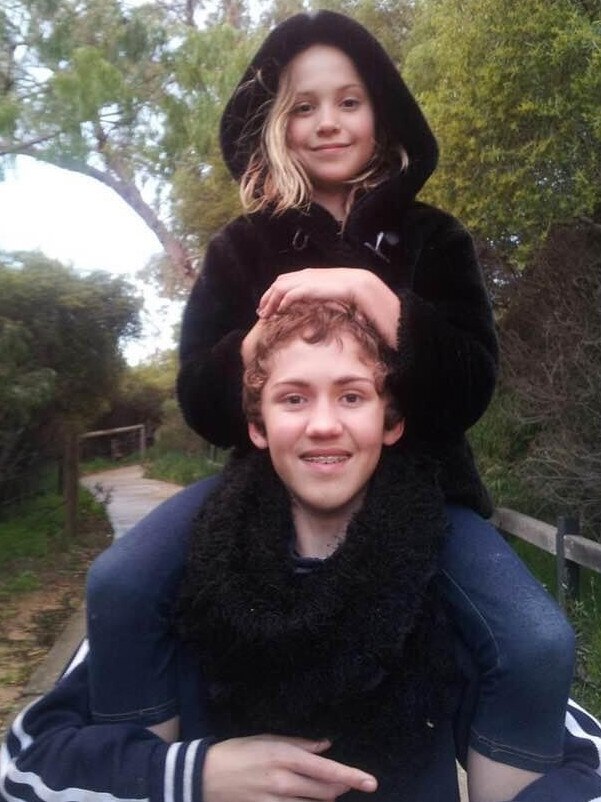

My son’s name was Cosmo. He was 22. He was beautiful, sensitive and talented. He was studying fortepiano – a type of early piano – at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts under his brilliant teacher Geoffrey Lancaster. He loved his little sister Harper, and his best friend Neisha. He had just begun a budding romance with the pastor’s daughter at the church he attended, where he was much loved. He was close to me, his Dad and his grandparents and had many close friendships. He loved skating and more than anything else in the world he loved his precious fortepiano. He practised for hours every day. He memorised Beethoven, Mozart and Haydn. He talked passionately about the history of the instrument, the technique, the mechanics – to anyone who would listen. He was in his third year at WAAPA and wanted to go on to do honours and a PhD. Geoffrey told me he had a gift for tuning the fortepiano and he would have become one of the few people in Australia with this gift. His future looked rosy and bright.

He died of an opiate overdose on January 28, 2021. His light went out when it was at its brightest. He’d spent the summer skating, going to the beach, playing fortepiano and having fun with his friends. He got 93 per cent for his final exams. He played a stunning final concert at WAAPA and a wonderful house concert at Mum’s place to raise money to pay off his instrument. He was committed to his recovery and had many friends from his time in rehab. We all knew he was fragile. We knew he had a fatal weakness. We were all watching him closely and loving him hard. But we still couldn’t save him.

He had scoliosis and terrible neck pain. His teacher said he needed to rest and stop practising. He was on his summer break and didn’t need to practise, but he couldn’t stop. The fortepiano was his salvation. I kept offering him massages but he often said he was busy. His physio recommended he ask his doctor for muscle relaxants. She refused because of his drug history. So he turned to the internet. He found a synthetic opiate I’d never heard of. It’s a new designer drug they make in China, so new it isn’t illegal yet. I’m not going to repeat its name because when I Googled it, up it popped. A picture of two bags full of white powder. $170. Click here. It was that easy.

His father Sim found him. He died in the room he grew up in. Sim tried to rescuscitate him but no luck. The police came at 2am. I made the terrible, terrible drive to see him and hold him for the last time. Then came the grief. It was like being a mosquito smashed on the window of a ten-tonne truck. As Nick Cave says, “There is a vastness to grief that overwhelms our miniscule selves. We are tiny, trembling clusters of atoms subsumed within grief’s awesome presence.” He nailed it.

Many of you will know that Nick Cave, the godfather of Australian punk, lost his 15-year-old son Arthur eight years ago, and has since undergone a profound spiritual transformation. He often writes about grief on his Red Hand Files website, where fans are invited to ask him questions. The love and tenderness he shows his fans, and the way he articulates the grief process, is phenomenal. A friend read aloud his famous “Letter to Cynthia” – a Red Hand Files post that was later turned into a song – to me a week after Cosmo died. I clung to Nick’s words like a drowning woman clinging to a raft. There were other things he said that resonated with me also – I felt Cosmo’s presence everywhere in the weeks following his death. Nick wrote, “Within that whirling gyre all manner of madnesses exist; ghosts and spirits and dream visitations, and everything else that we, in our anguish, will into existence. These are precious gifts that are as valid and as real as we need them to be. They are the spirit guides that lead us out of the darkness.”

He was articulating my experience. He gave me hope. He said, “Call to your spirits. Will them alive. Speak to them. It is their impossible and ghostly hands that draw us back to the world from which we were jettisoned; better now and unimaginably changed.” We read out “Letter to Cynthia” at Cosmo’s funeral and I asked everyone to take a moment to focus on Cosmo’s radiance. My beautiful son. He had always radiated an innocent beauty. There was always something delicate and ethereal about him. He suffered greatly on this Earthly plain. It seemed as though he had landed in the wrong place at the wrong time. He belonged in 18th-century Europe, playing fortepiano with Mozart in Vienna.

I found solace in poetry. I took up reading and writing, trying to process the horror. One day I was reading EE Cummings, and the phrase “young death” leapt out at me. I took up my pen and used it as a springboard to write about the night Cosi died. It was painful to write but it helped me purge some of the trauma and charge I carried.

One desperate morning four months after Cosmo died, I sent my poem and a letter to Nick via his Red Hand Files, asking how he and his wife Susie dealt with the guilt and trauma of losing a child, because I was crushed by my guilt and battling to stay alive in the face of my trauma.

Cosmo’s first year was full of trauma. He had a terrible birth, a lumbar puncture at one month, and a burn accident at 11 months. Gabor Maté, a physician and renowned addiction expert, says studies show a high correlation between traumatic births and opiate use. The burn accident wasn’t my fault but from that moment on I lost my confidence as a parent and felt constant guilt about it. Cosi was a sensitive kid who didn’t cope well with our marriage breakup. He was bullied at school and became very anxious. His anxiety made me anxious and we got into an awful anxiety loop with each other. We loved each other desperately, but we struggled to connect, and the more I worried about our connection the more difficult it was. He became shy and awkward and spent a lonely year with no friends at school. Down the track he discovered the piano and came out as gay, although he had relationships with both men and women. I realised he was a sensitive artist, which explained a lot.

But I now suspect he was also on the spectrum. He had a phenomenal memory – he could recite 230 digits of Pi and could play the Moonlight Sonata by memory. He had a monomaniacal obsession with the fortepiano, and later, a monomaniacal obsession with drugs. He struggled to understand complex social codes – he had a lot of nervous twitches and no filter, an unusual voice and gait. I took him to a lot of counsellors but none of them picked up that he was on the spectrum. I wonder now how different things might have been had we known he was autistic and received support to help him.

Almost a year went by. One day I was meditating on what Nick describes as “the luminous super presence” our loved ones leave when they die, when I received an email from Nick’s manager Rachel Willis. She told me Nick had been incredibly moved by my letter and poem and wanted to ask permission to use it in his forthcoming book Faith, Hope and Carnage. I was gobsmacked. I’d written my letter so impulsively and hastily. I remembered I’d asked about his and Susie’s guilt, and now I felt mortified. I couldn’t believe I’d asked that. I asked Rachel to send the transcript in which Nick and Sean O’Hagan, whose intimate conversations spawned Faith, Hope and Carnage, discuss my poem and letter. “Not just a wonderful piece of writing but an act of enormous courage, and it articulates so complexly, so terribly the night of [the tragedy] … when I read it it moved me to tears.”

Of course I sent my permission. After a response like that, how could I not? A month later Rachel emailed me again. She said Nick wanted to know if I could record my letter and poem for the audiobook! I sent her a recording on Mother’s Day. Two days later the awful news broke that Nick’s son Jethro had died. I was in shock. How was he going to survive the death of a second son? Not long afterwards Rachel emailed again, to say that Nick would like to speak to me the next day.

Losing a child turns you into a hermit. You don’t want to go out. You don’t want to talk to people. You don’t want to pretend to be normal when you’ve been eviscerated. You just want to lie around and lick your wounds. I had social anxiety even with my closest friends, so how the hell was I going to be able to have a conversation with Nick?

He called the next day, at pains to make me feel comfortable. He needed to give me some direction on the recording for the audiobook but also genuinely wanted to know how I was. He took the same tone with me that he does with his fans on the Red Hand Files – patient and loving. He asked me about my meditation practice. I told him I used meditation to commune with Cosi, and I’d had several ecstatic experiences during which I connected with him within the heavenly place where he now existed. I told him a little about Cosmo’s drug use, and also about the intergenerational trauma that I felt I’d passed on to Cosmo – my paternal great-grandmother was locked up in an asylum for years, and her daughter, my paternal grandma, was also locked up and given electric shock treatments. Dad had to go and visit Nana in the asylum when he was ten years old, and he’d been a distant father, passing on his legacy of depression and anxiety to me – which I in turn passed on to Cosmo.

I told Nick I was so sorry to hear about Jethro and he spoke a little to me about his relationship with Jethro and said they still didn’t know the cause of his death. He told me that he hadn’t been able to sit still when Arthur died and I got the feeling that he was doing the same thing with Jethro – throwing himself into work to escape. He raved to me about my poem. I told him I only really wrote poetry for myself, to help me process my grief, and he urged me to think about publishing it. He also said: “Tiffany … I don’t know how to answer your question about guilt.” He seemed concerned that he had no answer or words of comfort for me. There was a silence down the line. Neither of us knew what to say to each other.

I sensed that time was ticking and they needed my recording fast, so I got off the phone and immediately recorded my poem and letter. Nick sent me a lovely email thanking me and telling me what a pleasure it had been to talk to me. I also got sweet emails from Nick’s publisher at Canongate and the people recording the audiobook telling me how moved they were by my poem.

Before I’d received my copy of the book some reviews began to trickle in. I was stunned to learn from one review that my poem was the catalyst for Nick to talk about the night that Arthur had died. I wept reading about it. He had the same knock at the door. The arrival of the police. The terrible news. Arthur’s twin brother Earl’s knees buckling just as my knees had buckled, then later, viewing Arthur as I had viewed Cosmo. No wonder my poem had moved Nick. There was much in it that spoke to his experience.

That act of crying is so important. It softens you. It stops the harsh, critical voices, the self-blame and criticism. Tears quell your rage and invite love and tenderness from those around you. In crying for Nick and Susie and Arthur and Earl, I felt relief from my own guilt and pain.

Finally my book arrived. Nick had signed it “To Tiffany, thank you so much for the use of your extraordinary letter and poem. It was the making of this book. With deep love, Nick.” I read it slowly, glued to the page, reading and rereading significant passages, completely blown away by Nick’s ability to articulate grief, loss, love, art and his spiritual awakening since the death of his son. Whenever I spent time with Nick’s book I felt soothed. It offered me respite from my horror. The final three chapters – which included my poem, Nick’s discussion of Arthur’s death and his final chapter on absolution – were riveting. Nick talked about his and Susie’s terrible guilt and shame. He said Susie was absolutely tortured by her self-loathing. Sean O’Hagan said: “C’mon Nick, it wasn’t your fault.” And Nick replied: “It doesn’t matter. We were looking the wrong way at the wrong time … and now everything we do is to seek forgiveness by making amends.”

This was the big lightbulb moment. This was the way I could find my way out of the terrible darkness. This is why I’m writing this now. Because I’m hoping my story will help all the parents out there whose children are struggling; whose children have died from suicide or drug overdoses; the parents who wrestle with guilt, shame and self-loathing; who did the best they could but still they failed. In his book, Nick talks about the recklessness he and Susie experienced when they began to recover, and I feel it too. Because the worst has happened to me now, and it no longer matters what my status is or what people think. My masks are down and all that matters is love. I messaged Nick with “Absolution” in my email title and one sentence in my email. “You answered my question. Thanks … to you and Susie.” He replied immediately: “Much love to you Tiffany.”

Soon after Nick’s book was released to rave reviews, his Carnage concert tour came to Perth. His manager Rachel had organised two tickets for me, and the day before the concert she emailed to ask if my partner Shaun and I could send her RAT covid tests so that we could come backstage. The idea of meeting Nick terrified me, but there was no turning back.

His concert was utterly thrilling. Beautiful. Mesmerising. Many reviewers have described it as a spiritual experience, and it was. Nick was clearly channelling his beloved Arthur in many of his songs. His music was ethereal and otherworldly – much like my beautiful son. My partner Shaun and I hung off every word, every song. Halfway through Nick dedicated a song to me, Sim, Harper and Cosmo. He said our names with such tenderness, and sang the song with such emotion, I cried rivers. The chorus rocked me. “Nothing else matters when the one you love is gone.” It got a huge round of applause, and several friends in the audience said they too were crying. Shaun and I were transfixed for the rest of the concert.

So. We went back stage and waited. Nick came out and said: “You’re beautiful!” and gave me a big hug. He was magnetic and charming. His band members were all lovely and kind. I asked him about the song he’d dedicated to us. He said it was from Skeleton Tree, but he’d reworked it for the concert. He said it needed to be really special for me. I asked him if it was possible to invite my family back the next night so they could hear it. He said, “Absolutely – I’d love to meet them,” and asked Rachel to organise tickets and backstage passes.

I told Nick his 1989 book And the Ass Saw the Angel was one of my favourite books and he said it was going to be made into an Australian TV series. I’d read and seen a brilliant Australian play called The Bleeding Tree when I did my masters in playwriting, and I recommended it, saying it had the same Southern Gothic style as Nick’s book. I asked him how his new book was going and he gave me a nudge and said: “Tiffany, our book is on The New York Times Best Seller list.” I was beaming from ear to ear. I told him Young Death was inspired by an EE Cummings poem. He hesitated and looked pained before telling me they’d read out an EE Cummings poem at Arthur’s funeral.

Nick asked what we both did for a living, and I told him a play I’d written was performing at La Mama Theatre in Melbourne soon, and that Shaun had written the songs for it. I also asked him to please thank Susie for me, for allowing him to talk about her guilt and shame in his book; that it helped me so much to know I wasn’t alone. He wrapped me in his arms when I asked for a photo. He blew me a big kiss when I walked out and told Shaun he was a lucky man. I felt incredibly happy. The meeting with Nick made me feel that it might be possible for me to feel joy again.