Cold Chisel at 50: battered but unbowed ahead of sold-out tour

Not so long ago, tour rehearsals for Cold Chisel involved imbibing high-octane stimulants so that this famously hard-living, hard-charging rock band could burn out stages nationwide. Things are a little different these days.

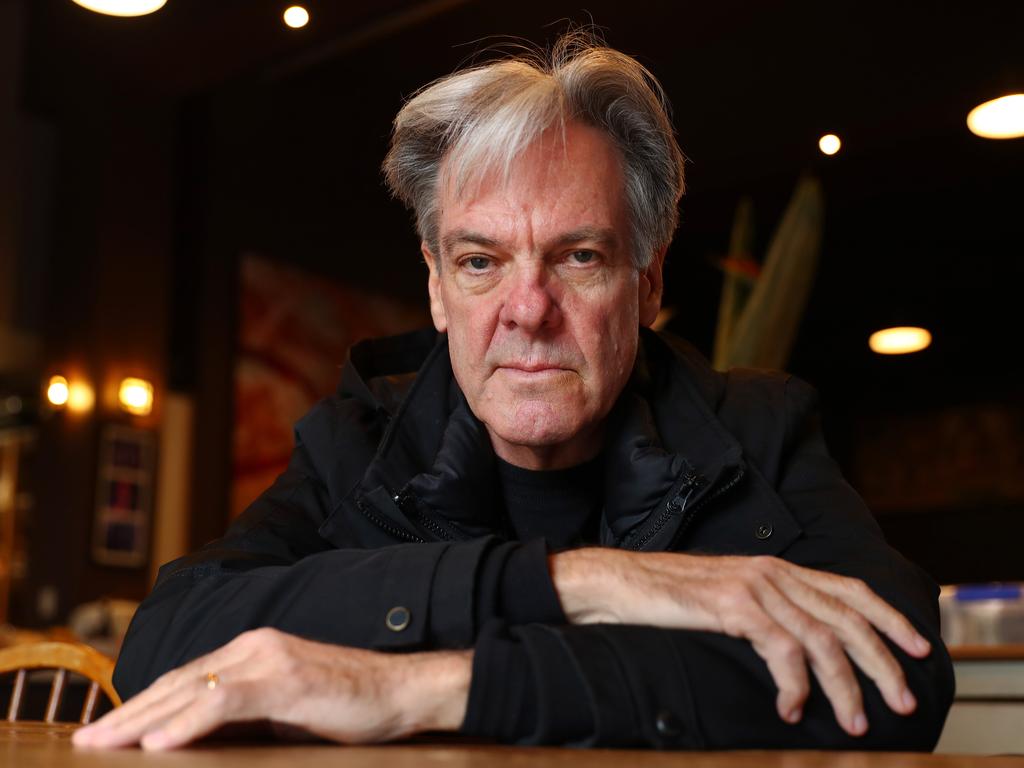

With a Marshall stack at his back, a glowing pedal board at his feet and a Stratocaster in hand, Ian Moss is bending soulful single notes and chopping through chord changes while frowning at the sound emanating from his instrument.

For now, only his music fills this large room, as he runs through an informal, free-form warm-up routine. As his left fingers play a flurry of notes and his right hand caresses the six strings with which he has built a life – and a reputation as one of the great Australian guitarists – the effect is akin to a jaguar flexing its claws to test its strength.

Everything, it seems, is in order for this king of the jungle and his fellow big cats, whose next kill awaits.

What’s happening immediately to the left of the Cold Chisel axeman is something that hasn’t occurred in 4½ years: all his bandmates are in the same room and they’re about to start playing together.

The quintet is about to resume a long-running story that contains no shortage of drama, heartache, fistfighting, cashflow troubles, excessive alcohol and drug consumption, self-belief, death, pride, brotherhood and tinnitus.

Oh, and some of the best songs ever written and performed in Australian music history. The great pen in the sky is inked and poised, ready to start scribbling this next chapter. Whether it’s the finale is unclear.

“All right!” Jimmy Barnes announces into the microphone, drawing Moss’s noodling to a stop and prompting Don Walker’s hands to move through a series of piano chords that signal one of the most beautiful songs in this mighty band’s formidable catalogue. Phil Small soon joins him in laying down a bass groove.

These five musicians haven’t played a song in each others’ company since February 9, 2020, when their highly successful Blood Moon tour drew to a close on a rainy night at a winery outside Brisbane, having played to about 200,000 people across 14 outdoor shows all up.

The finale then was the band’s traditional set closer, Goodbye (Astrid Goodbye), a breakneck rocker originally released as a single in 1978 – later rerecorded for second album Breakfast at Sweethearts (1979) – that has always seen Barnes straining the upper end of his vocal register while the musicians ploughed towards a terminus that was both inevitable and impossible to return from.

But just after midday on this Tuesday in mid-September, with a handful of people in this inner-city Sydney rehearsal room including Review, the first song these five men reach for is a fascinating choice.

It’s not Khe Sanh, or Forever Now, or Flame Trees, or Choirgirl, or My Baby, or Cheap Wine, or Bow River, or Saturday Night – any of the 15 or so FM radio standards that will unavoidably form the backbone of each night’s set list on its upcoming tour. These are some of the songs on which generations of Australians have been raised, and in turn raised children of their own, who’ve grown up with the unique taste of Walker’s lyrics, Barnes’s voice and Moss’s riffs.

No – the very first song they reach for is All For You, which Barnes begins by singing soulfully:

I get home, clean up, put on my best shirt

I put on my good shoes

My arms are hard from what I do all day

And it’s all for you, all for you …

A deep history lies within this song selection. Written by Walker and recorded in a one-off studio session in late 2010, it also marked the band’s final recording with drummer and songwriter Steve Prestwich, who died in January 2011 following surgery to remove a brain tumour.

As I drive over by the steeple, by the hill

The rain is gone, the night is new

The constellations are coming out again

And it’s all for you, all for you …

Prestwich’s death at 56 bonded the four remaining band members in grief. It shook them to their core, prompting much soul-searching before they reached the eventual decision to continue making music together while they still lived and breathed.

As Barnes reaches the chorus and closes his eyes so that the notes emerging from his throat mirror those in his memory, the bespectacled man behind the drum kit is grinning like a kid on Christmas morning.

It’s all for you, there are songs in the world

I’m singing softly as I drive

It’s all for you, ’cause you’re the only girl

And I’m young again

And it feels so good to be alive.

All For You was the title track of the band’s greatest-hits compilation, also released in 2011, once the quartet had elected to continue. But for that dream to become a reality, it needed a new drummer, and it found one in an unlikely place: New York City, in the shape of a Cold Chisel fan who was married to an Australian woman, who was also approaching her own terminal decline.

His name is Charley Drayton, and his teeth are gleaming white as he keeps the beat to this marvellous love song while his own heart beats for the music these five men make together. With his distinctive swinging drum style, he has kept perfect time for the past 13 years while the band wrote, recorded and released three more albums and undertook three major tours.

The newest of these is only just gearing up, and it’s the largest one yet: more than 200,000 tickets have been sold across 26 shows in Australia and New Zealand, and its box office gross sits somewhere in the region of $25m, which will make it the year’s most popular tour by an Australian act.

It feels so good to be alive, sings Barnes: he feels that sentiment deep in his bones, having come all too close to death not so long ago after undergoing his second open-heart surgery late last year.

Another recent stint in hospital for a related health concern is keeping him in constant contact with a team of healthcare workers, whose goal is to gird him with the tools to lead the band he has fronted and loved for five decades.

After that sole run-through of All For You, though, there’s nowhere else for these five men to go, at least for the moment. They sound great and they’re itching to continue – but Barnes has a medical appointment across town.

In the past he was far more likely to have blown it off, following a lifetime of favouring rock ’n’ roll over rest ’n’ rehab, but at 68 he has learned the value of listening to expert opinions. There’s a lot riding on this tour and, for it to work, the man with the microphone must be well.

As the song winds through its last few bars with a tasteful Moss solo, a final chord flourish and Drayton tickling his high-hats, there are a few beats of thoughtful silence that is soon broken by Barnes.

“All right – thank you very much, we’re all done with rehearsal,” he tells his bandmates with a grin, drawing laughter from all in earshot shortly before he leaves the room and leaves the four other big cats to flex their claws in his absence.

Formed in Adelaide in 1973, Cold Chisel is that rarest of entities in show business: a rock act that has reached its 50th anniversary milestone and is still willing, able and hungry to perform the rich catalogue of songs that has endeared it to millions.

Since 2011, the band has toured every four or five years. Last time, ahead of the Blood Moon tour of 2019-20 – which was executed amid the nation’s horrid summer bushfires and finished up shortly before the Covid pandemic began – the musicians were uniformly unsure what the future held for Chisel.

In late 2019, Barnes told Review: “There’s a good chance it’ll be another five or six years before we do something else, and everybody’s going to be in their 70s. I just think, well, I’ll wait and see if we’re going to be able to. Because Cold Chisel is a f..king high-powered band. It’s intense and it’s very taxing to do, and I don’t want to go out and do that half-arsed.”

Five years later, he’s approaching his old band with a fresh mindset, having recently notched another ARIA No.1 album with its compilation 50 Years – The Best Of, which featured a slinky new single titled You’ve Got to Move.

“Normally we futz about, and we go and make records before we go on tour,” Barnes says. “And normally, by the time you finish in the studio for three months, fighting to get your bits the way you want them – by the time we hit the tour, we’re a bit frayed, and it’s a bit scattered.

“It’s really good that we’re coming in with one new song, and being able to just play the songs that we love. And this might be arse-about; I think at some point we might lead on to maybe making a new record as well. It feels really good, and it’s a different approach – as opposed to the pressure cooker that we normally put ourselves in.”

Before that first band hit out with All For You, we’re sitting out the back of the rehearsal studio in Sydney’s Moore Park and chatting over coffee, while a large bull mastiff cross belonging to the tour production manager prowls around us in search of our affection, which we gladly give in the form of forceful pats.

As a speaker, Barnes possesses a rare magnetism that has long endeared him to journalists. Anthony O’Grady’s excellent 2001 biography of the band, The Pure Stuff, quotes Walker emphatically: “I have never encountered anyone with a better combination of intelligence and charm than Jim.”

Slung over the singer’s shoulder is a portable PICC line that feeds him intravenous drugs for six weeks while he recovers from a staph infection, for which he was hospitalised in early August to undergo two urgent hip surgeries, front and back.

Recently bed bound for three weeks, he continues to walk with a limp, but his physiotherapist has prescribed a unique regimen to rebuild his strength after watching footage of the highly physical way in which Barnes has always performed on stage.

“He’s got me lunging all over the f..king house carrying 40 kilos; he started me yesterday big time with more weight, doing these singing lunges, and my legs are f..king killing me,” he says, grimacing. “So the hip is really good; it’s just building up all the muscles again.”

The danger of writing about this band across the decades has been to get sucked into focusing on Barnes, and this time Review is determined to resist his charms, at least temporarily. It’s in asking him about the drummer that we luck into an untapped vein.

“Charley’s relentless; he’s the king of groove,” Barnes says. “Listen, if we hadn’t met up with Charley, I don’t think Cold Chisel would ever have got back together after Steve died. We were so shattered, and Steve was so unique as a drummer. When he died, we just didn’t think we’d ever find anybody to fill his shoes. We didn’t think we’d play again.

“It was by chance that somebody mentioned Charley Drayton; at that time he was here because the love of his life was dying. He was mourning as much as we were.”

That love was Chrissy Amphlett, the Geelong-born frontwoman of rock band Divinyls, who was then suffering from the debilitating effects of multiple sclerosis and breast cancer.

“Because of his connection with Chrissy, he was so aware of Cold Chisel,” Barnes says. “And it was just sort of, ‘Let’s just have a play together.’ It was this match made in heaven – and over the years we’ve both been healing each other.”

Today is the singer’s first visit to the rehearsal room, and both he and his wife Jane Barnes are filling the space with good cheer, which she’ll later document on Instagram. But a week prior, the band’s rhythm section got together to rehearse as a three-piece, sans guitar or vocals.

In a separate interview with the pianist and bassist, Walker says with a smirk, “Phil and I and Charley have done four days last week, so hopefully the back-end of things is a little bit tighter than if it was actually the first day. We’d never done that before, so it was a new idea – but we agreed at the end of the week, it’s how we should have been doing it all along. Definitely the way to go, to really get into the nuts and bolts of what Phil and I do.”

“Rather than just guessing,” adds Small, 70, smiling. “You don’t realise, after all these years, that you’ve probably been interfering with each other, rather than [working] as a unit. It gave us the clarity to see these things as well, not having the vocals or the guitar there. The things that aren’t working, they do stand out, and that’s what we worked on. I think it’s going to make a big difference.”

When Drayton joined in 2011, it necessitated a relearning process. “It took us a little while because there’d be places in songs where, for 40 years, we had sped up together – all together, and we don’t think about it, because we all do it together,” says Walker. “Whereas Charley comes in, he’s new – he just plays the song dead accurate, and we find that we have to concentrate to make it sit.”

“When you listen back to some of the early recordings of the live shows – f..k, it’s like Mickey Mouse!” says Small. Too fast? “Oh, f..k yeah. I think it was reasonably tight, but it was just damn too fast. But also, in those days too, we were all quite young and silly; there was a lot of illicit stuff getting around as well, and I think that helped us along that speeding up track.”

The third and final band interview is with the drummer and guitarist, directly after the band had just run through All For You. Moss has just returned from playing a gig in the Maldives and he opts to sit on the sunlit side of the table to soak up more rays.

Review’s first question to this pair is a simple one – how did that feel? – and the response quickly and unexpectedly sidesteps the superficial in favour of digging into the deep and meaningful.

“There’s a music that’s like medicine in that songbook; then there’s us,” Drayton begins. “There’s some healing in us playing together, because we play one way together different to how we play with other musicians. So to have just played one song together again, and …”

Here he takes a 10-second pause as something inside him wells up and spills over, prompting him to weep. Noisy birds wheel overhead on this blue-sky Sydney spring afternoon; Moss and I wait until he’s able to continue speaking.

“It’s emotional because we’ve been through a lot to get back here and I love playing music with these guys,” says Drayton. “I always knew that we’d play music again. That’s my thinking, but we just hadn’t landed on when. That’s initially what brought us together: playing music was about healing, and in every chapter we’ve come together, we learn the value of life. We have music at the top – that’s the medicine. But it’s healing right now. That’s why I’m feeling some happy joy, because we had to prepare ourselves to get here, you know?”

As the band ran through that song, the drummer couldn’t wipe the smile from his face. “Hearing him sing, hearing us how we listen to each other; we’ve grown in our time together, you know?” he replies. “And it’s happy to feel where we are, and where this is going to go now. Look out! We wouldn’t be sitting in front of you thinking, ‘Eh, we’re gonna do this at 99 per cent …’ It’s not gonna happen. We’re all in; 100 per cent or nothing. Right?!”

He directs that last question at his bandmate, who has been listening quietly beside him. “Well said. Yeah, I can’t top that,” Moss, 69, says, chuckling. “I’ve been a little bit all over the shop with travelling around and getting back here from overseas. I’ve got a little bit of homework to do, I’ve just realised. I mean, most of that came back to me, but I’d completely forgotten where my backing vocals were in that song. I’m focused now. I’m glad the gig’s not tonight or tomorrow.”

At 59, New York-based Drayton is the youngest member of the group. His CV is outrageous: he’s toured with the likes of Keith Richards, Bob Dylan and Paul Simon, and that’s him playing drums on the B-52s’ 1989 single Love Shack, too.

He was a fan of this band’s music long before he was asked to join: when he met his wife-to-be Amphlett and Divinyls co-founder Mark McEntee in the US in 1990 – then later visited our shores for the first time in 1993 – he heard a chorus of assent from Australian music fans in the know: Cold Chisel will catch up with you, he was told repeatedly.

They were right, and his eventual invitation to join the band was spookily foreshadowed by Amphlett, who died of breast cancer in 2013, aged 53, after giving her last performance on an Australian stage with Cold Chisel on December 6, 2011, when she joined her husband and his four bandmates in the encore to sing Saturday Night in Adelaide.

“We were sitting together when we heard the news about Steve’s passing,” recalls Drayton. “I eventually said to her, ‘Hey, what do you think happens when Cold Chisel loses a brother?’

“She was pretty silent about it for a little while because here she is, now living the same field of life like Steve [with cancer]. And when she responded with her wisdom, her intuition, she said: ‘If Cold Chisel decides to play again, they’ll come looking for you.’ And in the same breath, I said, ‘There’s not a chance in hell that could happen.’ ”

Drayton, says Moss, brings “a beautiful musicality that at the very least is incredible – not only in the playing but in the personality, there’s an incredible stabilising and calming factor that he’s brought to the band. It just seems to be a band that’s prone to chaos, maybe for more than one reason. But I just love the fact that Charley, 100 per cent of the time, is his own man. He’s got his own definite idea of how the songs should be played, and how the band should be played with – and he’s right.”

After a sushi lunch break, the band opts to begin working as a quartet on You’ve Got to Move, the newly released single from the chart-topping greatest hits compilation, which they recorded during the Blood Moon sessions five years ago but haven’t touched since.

Nobody’s sure if the singer will return after his medical appointment, so the rhythmic trio brings the guitarist in on some of what they’d been trying out last week.

This decision to press on makes sense since he’s the main vocalist on the recording – a product of that distinctive way in which Barnes and Moss have alternated lead vocals throughout much of the band’s career, with their blend of hard-edged burr and soulful honey, respectively, forming a potent combination in their initial 10-year run before disbanding in 1983. Moss sings its opening lines:

Get up in the morning, take a piss and look around

Look at where I’m goin’, not a worry to be found

Look at where I’ve been, look at you and look at me

Any way you cut it, this is not the place to be …

But a little after 2pm, Barnes limps back in sporting a white T-shirt, over which he soon adds a black hoodie. He doesn’t announce himself, nor do his bandmates stop the song to greet him; he simply finds a stool on which to sit in the centre of the quintet, facing the drums, with his laptop perched on a road case. Its screen shows the lyrics, while its lid bears the Scottish flag of his birth country.

After the second take, there are brief discussions across Walker’s piano; Drayton, still smiling, alternately hits his vaporiser and snaps some phone photos of his bandmates from across the kit.

After the third take, Barnes begins stage-directing by pointing at Moss’s microphone as a visual reminder for when he’s due to take lead vocals. The guitarist’s solos, meanwhile, are totally different each time, drawing on the impressionistic, free-form genius that connects his brain to his fingers.

By the fourth take, as they finesse the desired tone of their backing harmony vocals, Drayton is twirling his orange sticks as they inch towards that key-in-lock swing feel that they all desire. Our time in the inner sanctum is up, but their work together on this newest chapter is only just beginning.

As they slam through the chords, Barnes can be seen bouncing his left foot while he sits on the stool, microphone in hand, concentrating on the sound they’re creating. His legs are f..king killing him, but while this music fills the air they’re young again, and it feels so good to be alive.

Cold Chisel’s 23-date national tour, titled The Big Five-0, begins in Armidale (October 5) and ends in Sydney (December 4).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout