Tower of song

How a boy from Grafton went on to define Australian music by simply watching the world go by.

Don Walker’s hands are steady as he presses his fingertips against the black and white keys of a piano and turns his mind to a valuable musical lesson that was first presented to him many years ago. Inside a huge, rambling farmhouse near Grafton, NSW, the 10-year-old boy learned to play under the watchful eye of a woman named Dot Morris.

While his brother sat outside on the veranda, waiting for his turn, Morris taught the boy the fundamentals of what would lead to a mastery of this instrument and, eventually, a slow ascent to the peak of popular music as one of Australia’s best-known songwriters and pianists.

Sitting on stage inside a beautiful venue named the Old Museum in central Brisbane in early June, where he will perform later this year, Walker’s hands are steady at the piano because of something he was taught more than five decades ago. At the Grafton farmhouse, Morris would place a box of matches atop each hand and ask him to play something, always with curved fingers. If his hands strayed from their neutral position and either matchbox fell, he would have to start again.

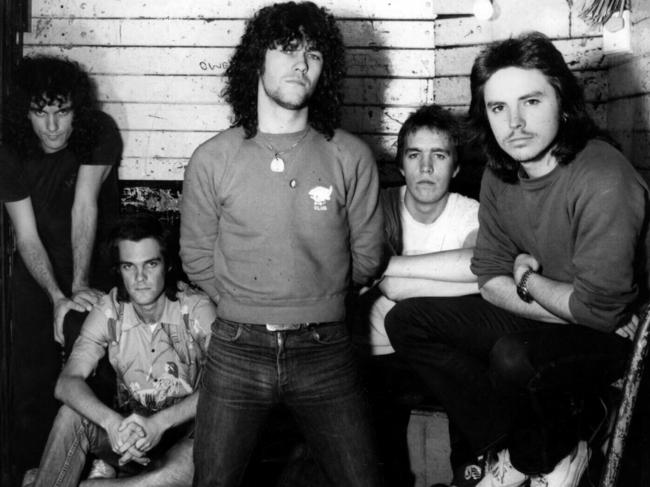

It’s a simple but effective exercise, even though — as Walker admits with a smirk while playing an ascending bass scale — many of these fundamentals wouldn’t quite work when playing with Cold Chisel, the lively and influential rock band he co-founded in Adelaide in 1973.

With Morris, if he made too many mistakes, or if his teacher sensed he hadn’t practised seriously enough during the week, he’d receive a swift crack across the knuckles. Walker didn’t feel that sharp pain often, or at least not as often as his brother, Richard.

Dot Morris was his teacher for his first three or four years of piano lessons. How often does he think of her when playing today? “Not often,” Walker replies, looking down at the keys. “I’m not proud to say that. She’s a person for whom I have enormous respect in every way.”

In starting his musical education at age 10, Walker was late to take a seat before the keys; many children — and certainly child prodigies — tend to begin playing at half that age. Did he like it immediately? “No,” he replies. “There’s no enjoyment in the first year or two of playing the piano. For every normal kid — which me and my brother were, especially normal farm kids — you want to be out in the fresh air, running around the farm, throwing things at each other.

“Instead, you’re forced by your parents for two years to go once a week to this lesson, and to practise in between. For the first 18 months or so, there’s not much return in enjoyment because you can’t play anything that you could get any pleasure out of. It’s the hard mechanics of teaching your fingers to do something that’s utterly unnatural. Dot knew that; she was a very good player, and had a beautifully tuned piano.”

Despite the initial lack of return on the time he invested in the instrument, the 10-year-old stuck with it, because he did what he was told. At that time, in the early 1960s, there didn’t seem to be any connection between the guitar-based popular music he heard on the radio and what Morris was teaching him. The notion of joining a band had not yet occurred to him, and wouldn’t for several more years.

With the benefit of hindsight, Walker looks back on those early lessons with Morris as a wonderful gift. “Certainly nobody at that stage thought that you could actually make a living out of playing the piano — nor would that be desirable,” he says. “The main game going on in that era was the studies at school. In my family, education was seen as the key to everything. That’s how you could get from the farm to anywhere in the world. You could be anything.”

■ ■ ■

In 2009, Walker published one of the strongest and strangest books to emerge from the fingertips of an Australian rock musician. Shots was an elliptical memoir with a mesmeric writing style that favoured long, flowing sentences that painted places, people and periods with stunning prose. It was light on the juicy gossip and anecdotes that Cold Chisel fans might have hoped for, but heavy on insight into the idiosyncratic rhythm to which the clock in Walker’s mind ticks.

In its opening pages, he describes a classroom where he and his fellow students — aged from five to 15, “bare feet and farm hair shaved and hay-stacked in all directions” — being taught to chant a poem titled The Village Blacksmith. He writes: “I know what’s unnecessary and don’t clog my head which at such times flies out through the trees, the church and the tiny community hall nearby to the railway track, north to Brisbane, south to Sydney, so many long slow fly-blown summer afternoons, so many years away.”

Shots came about after Chris Feik, publisher at Black Inc, approached Walker to ask if he had any ideas for a book. Its series of scenes were initially written as byproducts from the hard work of matching words to music. “With songwriting, you’re basically trying to get a whole world into sometimes 12 lines, and a very limited number of syllables,” he says. “It can get very anal. It’s like a Rubik’s cube; you can have 98 per cent of a song written, and be struggling with half a line somewhere for weeks.”

To combat this, in the 90s, Walker began each morning with a blank sheet of paper and the intent to “just vomit out words; a recollection, a joke, a reminiscence — anything,” he says. “Just make a white page black, and then another one, for 40 minutes. Then when you come back to the real, small, focused problem, somehow that process can blow the barrier away. That’s how I began writing these pieces, and the effect is intended to draw you into a stream. You shouldn’t notice, really, the lines going past in Shots; it should be just like a bit of a movie.”

About 18 months ago, Feik approached Walker again with the idea of collecting his song lyrics into a single volume. While initially sceptical, the songwriter warmed to the idea as he began whittling his catalogue down from a career total of about 450 songs to the 240 or so that appear between the covers. These works span the years 1970 to 2018 and include material written for Cold Chisel, Jimmy Barnes, Catfish, Slim Dusty, Busby Marou, the blues-folk trio Tex, Don and Charlie, and for himself as a solo artist.

True to its name, Songs is a book heavy on lyrics: situated side by side, one after the other, dozens at a time, grouped by eras in chronological order. The effect is hypnotic: here is the lifetime accumulation of a man who has spent countless hours observing, listening and thinking about people, then grinding the skeletons of these stories down into their bare bones.

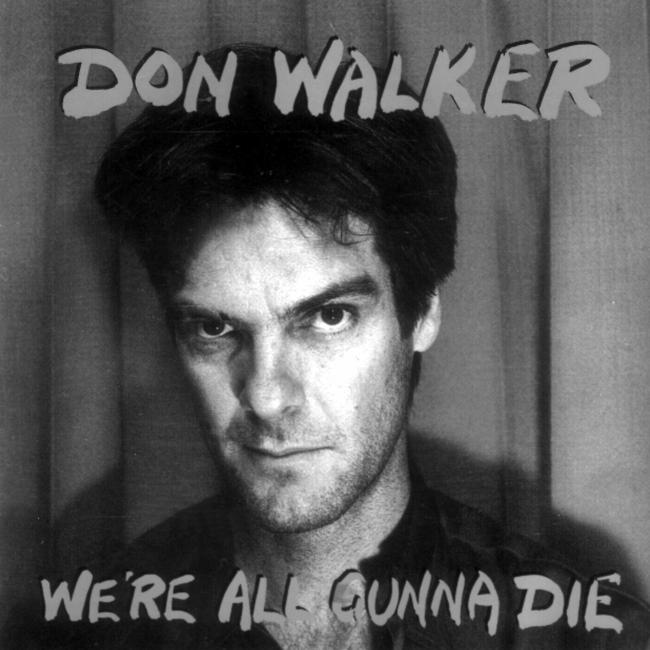

In the early 90s, when he was writing for his solo album We’re All Gunna Die, the imagined monologue of a man in jail for murder (“If it hadn’t been for whiskey I’d be free as any bird”) rubs up against a dialogue between lovers in a toxic relationship (“You’ll say my promises are hollow / But when all the crying’s done / You know I’ll talk you round”), followed by the freight-train stream of consciousness belonging to a possible psychotic (“I just wanna have a party / And see what I can kill”), then a scene set amid animal cages, lion tamers and strongmen (“I paid up my money and waited in line / And the circus was just like home”).

On and on they roll, Walker’s stories real and imagined, in dreamlike composite. While the depth and breadth of his catalogue seems mighty impressive to a casual reader or listener, the collection will either inspire or — perhaps more likely — terrify his fellow songwriters.

Its 280-odd pages amount to an Everest of published work, and even without the musical accompaniment, his facility for scenes, characters and evocations is evident with every turn of the page. In the 2012 Cold Chisel song Missing a Girl, for instance, he makes this observation at an airport:

Looking through the tarmac rain

At the rows of giant birds

They’re all feeding at the gates

There are tails from all over the world.

While his humour is often drier than the sand you’d find at the foot of Uluru in the middle of summer, occasionally you can feel a smile cracking into a grin as he pursues an idea to its comedic conclusion. Take My Girl, which appears about halfway through the book:

I’ve had French princesses for a night and a day

Spoonin’ Beluga where I cannot say

Air hostesses demonstrating for me

The safety procedure in their lingerie

PhDs who could bust a D-cup

Checkout girls wanna be taped up

Older women wanna mother a son

Now I’m a man and she’s the only one

And here she comes …

A song written for Slim Dusty titled Looking Forward Looking Back is among the simplest in terms of its language, but among the most profound in meaning, given that he was asked to write something that would summarise the astonishing recording career of the country music great. What Walker came up with became the title track for Slim’s 100th album, released in 2000, three years before he died at the age of 73:

Looking forward, looking back

I’ve come a long way down the track

Got a long way left to go

Making songs from what I know.

Though written with an older man in mind, those words could also apply to Walker now. He was always the elder of Cold Chisel, often depicted as the straight man in what was a wild and woolly quintet that fought its way through pubs to eventually play arenas. He alone attempted to manage the band in its early days, before gratefully passing that torch to a succession of individuals so that he could concentrate on creative endeavours.

Apart from the impending publication of Songs, Walker has several other projects on the near horizon, including a solo tour and the likely release of new Cold Chisel music before year’s end.

But if his second book is as tantalisingly light on details of the surrounding stories that fed into his music as Shots — which is also being re-released in hardback — then a series of recent YouTube videos serve as helpful companions. This footage, recorded earlier this year, shows Walker behind the wheel of a Holden station wagon, driving around NSW’s Blue Mountains while thinking aloud about his work in response to questions thrown at him by a passenger. These clips are focused on single songs yet reveal Walker’s songwriting process in great depth, punctuated by occasional exclamations based on what he sees on the road in front of him.

“Look at this bloke,” he mutters at another driver while speaking about the 1988 Catfish song In the Early Hours, momentarily interrupting his train of thought.

In one of these videos, after several minutes of explaining the origin of the 1978 Vietnam War-inspired song Khe Sanh — which was observed from the naive perspective of a man in his mid-20s with little life experience, “just writing for the sake of dreams” — Walker concludes that he’s quite proud of his younger self.

His interlocutor speaks for a great number of Australians when he replies, “You should be.”

At this, the songwriter almost breaks into a smile, heartened by the acknowledgment 41 years after the release of his most popular work, which also happens to open his second book.

“I think I should be, yes,” he says with a nod, eyes on the road, looking forward, looking back.

Songs is published and Shots reprinted on Monday (Black Inc).

Don Walker’s east coast tour begins in Belgrave, Victoria, on August 29 and ends at Out on the Weekend festival in Melbourne on October 12.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout