No manager, no label, no real plan. After more than four decades in the entertainment business, much of it spent in the spotlight here and abroad, one of Australia’s biggest pop stars had unplugged herself from the music industry’s conventional machinery. And here she was about to step on to a gigantic stage at Sydney Olympic Park – amid whispers that her once-glittering career was now on life support, that proverbial defibrillators should be at the ready.

But to anyone who saw Tina Arena with microphone in hand that day in February 2020 there was no inkling that anything was amiss. Ever the professional, Arena – though vastly underweight by her own admission – rose to the occasion and blitzed the stadium crowd with her lethal weapon of a voice.

She was performing a late afternoon set, after Delta Goodrem and Ronan Keating and ahead of the likes of Alice Cooper and Hilltop Hoods – a motley line-up of musicians you wouldn’t see together ordinarily. But this was no ordinary gig: the day-long Fire Fight Australia bushfire relief fundraiser featured many of our biggest local stars alongside some of the international acts touring at the time.

Backstage, Arena’s fellow performers had their posses of supporters and hangers-on to pump their egos before and after showtime. Arena, a newly independent artist, had none of that. “I walked out on stage with no record company, I had no management – and I had the best time,” she says three years later, sitting in her home in Melbourne’s inner southeast. “I was on my own; no one was looking after me.” When they asked if she would be involved, she says, “I was just like, ‘Yeah, sure. When do you need us? Oh, cool. No worries. We’ll be there on time, with a smile on our faces. Promise you.’”

Not long before, Arena’s long-term relationship had come to an end. She had also begun a painstaking process of “cleaning up her backyard”, as she describes it. In a move rarely seen by such an established artist, she severed most of her professional relationships, retaining only a lawyer and accountant, and had them conduct a forensic accounting of her creative and commercial life to date – which included tracking down and reviewing every contract she’d ever signed – while carefully building a new team of lieutenants from the ground up.

“My lawyer goes, ‘What are you doing all this for?’, and I said, ‘What if I dropped dead tomorrow?’” she recalls. “He went, ‘Well, that’s f..king morbid.’ But in the event something goes wrong, I want to make sure everything’s in order, and my boy’s protected.”

At the Fire Fight gig, alongside her band there were just two people in her circle: a stylist and her friend Fiona Gulin, who was also working as talent liaison for the concert’s promoter TEG Dainty. “It was the biggest stage that Tina had been on in Australia for quite some time, so it was a big deal for her,” says Gulin, who now runs a marketing consultancy. “It was a turning point for her, for sure.”

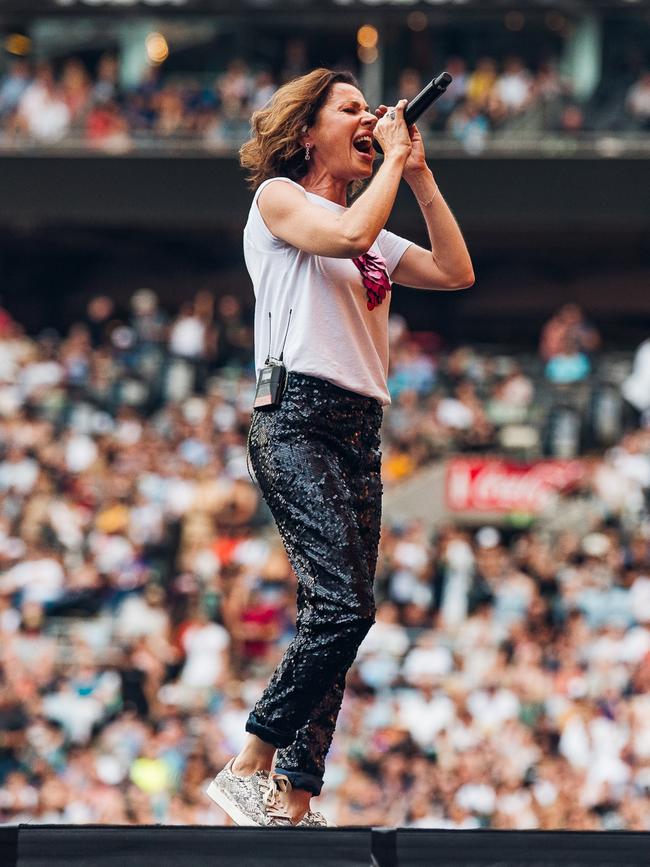

When Arena attempted to step into high heels backstage, she stumbled and toppled over. Spooked, she opted instead for the sneakers her stylist had fortuitously packed as a backup option. “There was a lot of stuff going on in my life,” Arena recalls. “I was, like, 47 kilos at the time. That day was very symbolic … February 16, 2020. I literally couldn’t walk in heels. I don’t know what I was feeling; I was quite lunar. That was the beginning of many, many changes, like a domino effect – and then I went out and did that performance.”

It’s a problematic quirk of our modern human nature that we come to take excellence for granted; even the shiniest bauble can lose its lustre after long exposure. Even so, at the televised event that included appearances by rock band Queen and a duet by John Farnham and Olivia Newton-John (in what would be the final public performance of ONJ’s life), Arena glowed fiercely. Wearing a white T-shirt with a pink sequined heart design, black pants and a short haircut, she prowled the stage like a panther. Allocated a slim slot in the 10-hour concert program, her four-song set opened with a single from her 1990 album Strong As Steel and ended with a hard-rocking cover of Divinyls’ Boys In Town.

Only a handful of people knew of the upheaval that was going on behind the scenes for her, but that’s the practised sleight of hand of a lifelong musical magician: short of incapacity or death, the show must go on.

For anyone who had underrated or foolishly written her off amid a lengthy absence from touring and a five-year hiatus from releasing any new music, her 18-minute performance was a potent statement of intent and a reminder of her formidable presence. Of that scorching Fire Fight set, Gulin says: “She walked out and nailed it. That’s her, though. It’s ingrained: when she needs to turn it on, she turns it on.”

On a wintry Wednesday in late June, Arena backs her hatchback out of her garage on a quiet street in Toorak and points the vehicle toward a television studio a short drive away. “Excuse the car,” she says. “It smells of cigarettes – my ex-partner used to smoke. I used to hate it, because it destroyed the car.”

As her headlights beam toward a main road, she says: “You know, I prided myself on being the only mum at a private school who had the shittest car. Everyone used to look and go, ‘That’s not Tina Arena…’ and I’d smile at them and go, ‘Hi!’ while they’re driving their $250,000 f..king Mercedes. I’d go, ‘Yeah, I worked for this, mate. I don’t know what you did, but I like it. I sweated for every tyre.’”

Arena is weeks away from releasing her 13th album – her first full-length release in eight years and her first as an independent artist, having issued all her previous albums with Sony or EMI, with total global sales estimated at 10 million copies. Promoting the new album is top of the agenda this evening, and it’s why we’re en route to Channel 10’s South Yarra studio for an appearance on The Project.

It’s another sign of the times: where previously her label would have assigned a phalanx of publicists to shuttle her to appointments, she’s now in the driver’s seat. As she prepares to spruik her wares, there’s mixed emotions: she feels pride for the new work – an autobiographical set of songs that cover a tumultuous period in her life – and pain for who she’s missing. Her 17-year-old son, Gabriel, is studying his final year of high school over in Paris with his father, her ex-partner Vincent Mancini. Her son’s absence weighs heavily on Arena. There’s a song about that on her new album, titled Mother To Her Child; in the chorus she sings:

Where you are now I’m not a part of

You should know that it’s a precious life

If you should fall I’ll rip my heart out

But I’ll be strong and I’ll be brave and wild…

As we crawl down Toorak Road in the hatchback we breezily discuss toll roads, favourite childhood lollies, and the idea of lowering the voting age to 16 – a topic set for discussion on The Project tonight. She points out a studio nearby where she recorded her vocals for the album. In conversation, Arena is curious and solicitous, and fond of a swear word for emphasis. She has strong opinions, but listens carefully to what others think and is open to changing her mind.

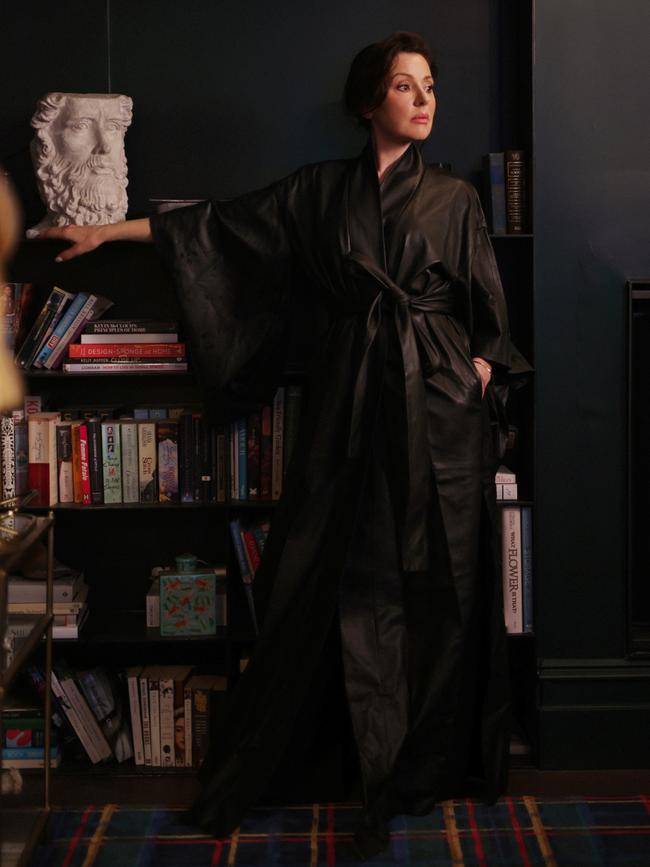

After accidentally taking a couple of wrong turns in peak-hour traffic she eventually pulls up in the studio’s car park. She steps out of the driver’s seat and into the building, radiating the intensity of one accustomed to being the centre of attention. Wearing a navy dress beneath a warm grey coat, her dark hair pulled back in a bun, bracelets clinking on her left arm and oversized gold-framed glasses, she is impossible to miss. A producer leads us into the green room and she casts her eye across a familiar spread. “You can see budgets here are expanding,” she quips, gesturing at a snack-laden table opposite a screen showing the live broadcast. “The obligatory camembert. We used to get about three cheeses.”

There is wine, though. Arena cracks open a bottle of pinot noir and pours a few glasses, including one for herself. Her sense of humour errs toward dryness at all times; what may come across as judgmental and snippy out of context is often delivered with an ironic smile in person. Hence the line about the cheese.

Earlier that day, US pop star Taylor Swift had announced her Australian tour would be confined to Sydney and Melbourne; it was a surprise, given the 33-year-old artist is at the peak of her popularity and could sell a million tickets here, as Ed Sheeran did in 2018, if she expanded her tour. Immediately before Arena’s slot with The Project’s co-hosts in front of a live studio audience, the program runs a package that includes effusive Swift devotees. “I don’t think everyone is going to get tickets,” says one. “But hopefully, all the true fans will be able to.”

And then Arena’s at the desk, turning it on. Asked about the title of her forthcoming album, Love Saves, she says: “I think love saves everybody – I’m just not sure whether everybody’s aware of that. It saved me from horrible thoughts; it saved me because I think that love is probably one of the most vital things that human beings need, next to water and food.”

It’s a thoughtful response to the question but the nature of the medium is to keep things moving, so she’s immediately asked about her world tour scheduled for later this year to support her album. It’s “excruciatingly independent”, she says, a reference to the fact she’s financing it herself after ending her five-album deal with industry giant EMI. The split, both sides say, was amicable. After more than 30 years in this game, where even the biggest artists can struggle to make a profit while attached to a label, she wanted to go her own way. Says former EMI executive John O’Donnell: “I could always feel a sense of [her] wanting to be in charge. I think she was during her time with us, but I think the move to being an independent artist is all part of that journey she’s on, and I respect it. I think it’s important to her, and so I think it’s the right thing for her to be doing.”

Some light-hearted banter follows in her slot on The Project. Could she imagine a music venue being named after her? “There’s no ‘Tina Arena Arena’, because it doesn’t make grammatical sense,” she says. A panellist suggests “Tina’s Arena” and she replies with a frown, “No, that sounds sexual,” drawing laughs from the audience and co-hosts.

Off-camera, a producer flashes a sign that the end of the program is fast approaching. “We’ve got one minute to go?” she asks. “How do I get a minute, and Taylor Swift gets 15? How does that work?” She’s smiling as she says this; having grown up in TV studios just like this one she knows how the game works. The question goes through to the keeper.

Inside the chest of the woman born Filippina Lydia Arena beats the heart of an unapologetic artist – with its curious blend of bravado and insecurity. That heart was beating hard when she jumped on stage at a cousin’s wedding at the age of eight and began singing to the first of many audiences who would be awed by her talent. The performance set in train a series of events that would put her in the public eye and at the centre of Australian culture over ensuing decades. That heart has been beaten, wounded, scarred, tormented and elated. The woman it sustains has been alternately idolised, celebrated and awarded, yet also underestimated.

As one of the greatest singer-songwriters of her generation, Arena’s experiences have been fed back into her art on record, screens and stages here and overseas; she has not just made an impact abroad, but found a second act and an entirely new audience in France.

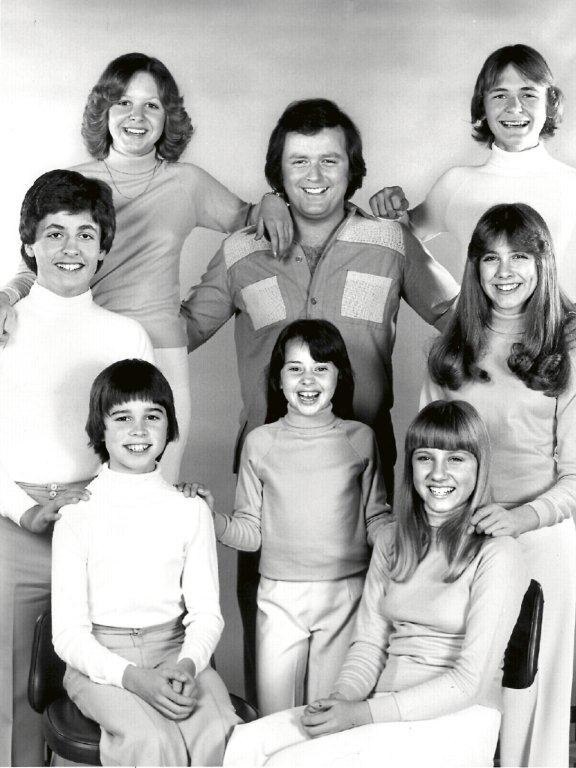

None of this came easily. With the blessing of her working class Italian parents, Giuseppe and Francesca, she became a fixture in the monocultural, appointment viewing era of Young Talent Time from 1976 to 1983, between the ages of eight and 15.

A girl whose ethnic-sounding nickname Pina was Anglicised to be more easily digested by middle Australia, Arena made her life – school, family and the rest of it – fit around the demands of the weekly variety program that put her on the map. She did it because she wanted to, not because she had to, and she has always spoken fondly about that formative time.

After navigating the relatively calm waters of television studios, she began swimming in the choppy seas of the record industry and eventually caught a massive wave with her 1994 second album Don’t Ask, and its hit singles Chains and Sorrento Moon (I Remember), both unimpeachable classics of the pop genre.

Like most of her material since then, those songs had her fingerprints all over them, a fact easily lost in a business where mass-market pop singers – especially women – are seen chiefly as interpreters, not songwriters.

Sorrento Moon paired an earworm vocal melody with a Latin-feel musical arrangement heavy on acoustic guitars and maracas. It was written with Arena’s adolescent experiences of holidaying on the Mornington Peninsula in mind. “Picture us just smiling there / We didn’t have a care,” she sang, and later, drawing on the same memory: “A picture of a child at play is how I feel today.”

But that was 29 years and 11 albums ago. Now 55, Arena has been consistently famous for 85 per cent of her life, and in that wrap-up on The Project there was a glimpse of her battle-hardened defiance in asking a question that most guests wouldn’t. It was the palpable tension of an artist receiving subtle indicators that they should feel nothing but gratitude in the few precious moments where live broadcast cameras and hot mics point their way.

It was the same story, more or less, the next morning when a Channel 7 crew arrived at the home she shares with her partner, musician Mattias Lindblom, to film a live cross to Sunrise while she sat cross-legged and barefoot beside the baby grand piano in her front room. Cut to packages on the missing Titan submersible, an upcoming $100 million Powerball draw and the opening of a Costco store on the Gold Coast. An hour in hair and makeup for five minutes on screen: that’s the deal. There’s utmost professionalism from all involved, but ultimately it’s a hollow experience, even if most of her peers in Australian music would be thrilled to get five minutes of prime-time TV air.

Even if Arena isn’t complaining – and, to be clear, she’s not – these are curious transactions. Watching her, a passage from her 2013 autobiography comes to mind: “After 20 years as a performer I’d become an expert at going through the motions, smiling when required, looking like I was interested,” she wrote of a promo schedule encountered at age 31. “But the truth was I just felt empty.”

So why does she put herself through all this? Simply because she wants people to know about her new music. She hopes you’ve heard Church and House, the two singles released so far, which were both co-written with Lindblom, Tania Doko and Michael Zlanabitnig, close friends and collaborators who share credits on roughly half the 11-track album.

She wants you to hear Devil In Me, a bustling pearl of a pop song speckled with jaunty keyboard chords and battlefield imagery and the most direct lyrics she’s ever written:

F..k you, I’m a Joan of Arc without a cause

But your eyes burn a hole through the thickest of walls

This is how empires fall…

-

‘I walked out on stage with no record company, I had no management – and I had the best time’

-

There’s talk of swords and shields. What do they represent? “You’re constantly being attacked in this industry,” she replies. “You’re a female. You’re opinionated. You’re not going to sit there and just do what you’re told – so you will be attacked. You do have to put your armour on, and you do have to sharpen your tools. It’s unfortunate, but it is the truth.”

Most of all, perhaps, she’s hoping you hear Outrun The Night, a subtle piano ballad with sparse instrumentation which, in its final minute, picks up the tempo and blooms into an extraordinary, full-band coda led by a lyric of optimistic affirmation to push aside the darkness and turn toward the light:

But you’ve got life

There’s plenty good around to live for

When you’ve got life

There’s very little left to die for

And you love life

Remember it’s what you came here for

You’ve got life.

And there’s Can’t Say Anything, a punchy, pointed track she says was inspired by both cancel culture and pandemic restrictions:

You can’t say anything anymore

Gotta get it out but you’re pushed to the limit

Can’t go anywhere anymore

I’m the first to go blind

I’ll admit I was in it…

Of course, Arena has had plenty of furious things to say about the Covid years, loudly chafing against restrictions on social and mainstream media – a bold stance that earned her ire and admiration in equal measure from a divided public. She was one of very few major Australian acts to stage a national tour, titled Enchanté, in the border-closure-plagued year of 2021. That May, she and her band visited eight cities and played to thousands of seated, masked fans at each show. “It was like those disaster films where someone’s coming out of a building that explodes a second after they get out of it,” recalls her lawyer Damian Rinaldi. “It had that sort of vibe to it where, as she toured the country, that particular city would close down a week later. At a time where everybody was running away from doing tours, because it was so fraught, she was determined to do it – and it was hugely successful.”

Looking back, Arena is proud of the tour but still incandescent about the world’s lengthiest lockdown. To ask her about it is to provoke a tirade: “I didn’t hear anybody complaining during lockdown other than me: ‘Why are we locked up? Where’s your science? What? Why?’ The fear was so much for me; it was choking me, I was like, I can’t cope with all of you being so fear-driven like this, and compliant. And why can’t you drive more than five kilometres? Guess what – watch me. So I did. I drove past my five kilometres. Am I a criminal now? You want to pull me up? Pull me up. You want to fine me? Fine me. I’m not the one with the issue here. The issue is, there is no logic. You have no right to do that. You are fining me. This is totalitarian. We don’t work like that.”

What’s behind this ferocious libertarian stance? “What we try and advocate in the music industry is that your job is to be a f..king rebel, actually,” she continues. “Your job is to challenge societal perspectives. It doesn’t mean you have to be right, but we all stood up and listened when Johnny Rotten wrote God Save the Queen. We took notice of David Bowie, one of the most extraordinary philosophical minds that ever graced our industry, by a mile, and a great human.”

Positioned conspicuously on her diningtable is a copy of Trent Dalton’s book Love Stories, and Arena has been quietly writing a new love story of her own with Lindblom, who produced and co-wrote the new album. The pair first collaborated in 2013 on a song titled You Set Fire To My Life – the lead single for her album Reset, which was written with her previous partner in mind. In November, Lindblom posted on Instagram: “No wonder then, wonders happen when she’s around. She lights up the room. An irresistible fire […] If there ever were to be a Queen of Australia, she’d be her. A Queen of hearts, why certainly mine.”

Lindblom is a tall, bearded Swede with a gentle presence. During my visits to their home, he alternately unpacks a new Moog One synthesiser with great enthusiasm; plays fetch with their effervescent Jack Russell terrier, Maia; uses a leaf-blower to clear around their pool, and quietly does some bookkeeping nearby, within earshot, as Arena and I chat in their living room.

“Music is so f..king important now,” Arena is saying. “I think the message of music is more important now than it has been in the past. I think it’s absolutely time to sit down and pay attention ... and try to understand where that writer is coming from.”

At this, Lindblom pipes up from the couch. “Music is just a tool; it’s a key to opening new worlds and adventures, if it’s done right,” he says. “If it’s beautiful, it can then translate and become a key for other people. If they love it, they can use it as a tool in their lives. But for me, it’s certainly a tool to experience life more fully, and I think that goes for you.”

“Yeah, without a doubt,” nods Arena.

“Your art can be a shield when you’re being attacked,” he adds.

“This record, for me, is my coat of arms,” she says. “It’s actually me just going, ‘This is who I am. This is what I stand for, and this is what I don’t stand for.’ It’s quite categoric, I think.”

I witness the warmth between them as Lindblom brings her cups of tea. He glimmers with pride when I compliment the new music they’ve created together, and she calls him “babe”. Arena’s personal life, the breakdown of her former relationship and the start of a new romance has sparked tabloid intrusion and angry ripostes: “My relationships, who I date, what I do, is really none of anybody’s business,” she says, glaring. How, then, should I describe their relationship? “I’m in a really beautiful place, and I feel very lucky,” Arena replies evenly. After a pause, she adds, “But I deserve it.”

Then she explodes in a cackle. “How about we finish the interview with that?” She leans toward the voice recorder on the table between us, dramatically deepens her voice, and says: “I f..kin’ deserve it!”

Well, it could be a great place to end the interview. But this self-assured line struck a discordant note against something I had heard ahead of our meeting, from a man who once worked closely with her. “She’s someone who beats herself up a bit too much,” said John O’Donnell, who in 2007 signed Arena to a record deal with EMI Music, which released her last four albums through to 2015’s Eleven.

“She has high standards, but I think she’s always running away from the people who partly defined the early part of her career,” said O’Donnell, who retired as EMI’s managing director last year. “I think she’s been purging their input for the whole time since, and I hope at some point, she relaxes, and finds a way to luxuriate in her incredible talent.”

Before she backed her proudly unpretentious hatchback out of the garage and drove it toward a TV studio for five minutes of airtime, the artist held a brief rehearsal session with pianist Mike Pensini. Sat at her Yamaha baby grand, Arena and Pensini ran through a few songs together, including Church and House.

With her eyes closed and her hands clasped together, Arena was a long way from that picture of a child at play she had painted in the lyrics to her most famous song. Instead, in that moment she was a picture of concentration as she leaned forward and gave a dazzling display of her vocal range, from the chocolatey low notes to soaring high runs.

To be in a small room as she carefully locked, loaded and fired her lethal weapon was breathtaking. This was a casual, unadorned performance for an audience of two, from a woman who hadn’t opened up her voice in more than a few days. “I don’t sing all the time,” she said with a sly smile, but to me, it sure looked and sounded like an incredible talent luxuriating at last.

Love Saves is released on July 14 via Positive Dream. Tina Arena’s tour begins October 7.

More Coverage

Andrew McMillen is an award-winning journalist and author based in Brisbane. Since January 2018, he has worked as national music writer at The Australian. Previously, his feature writing has been published in The New York Times, Rolling Stone and GQ. He won the feature writing category at the Queensland Clarion Awards in 2017 for a story published in The Weekend Australian Magazine, and won the freelance journalism category at the Queensland Clarion Awards from 2015–2017. In 2014, UQP published his book Talking Smack: Honest Conversations About Drugs, a collection of stories that featured 14 prominent Australian musicians.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout