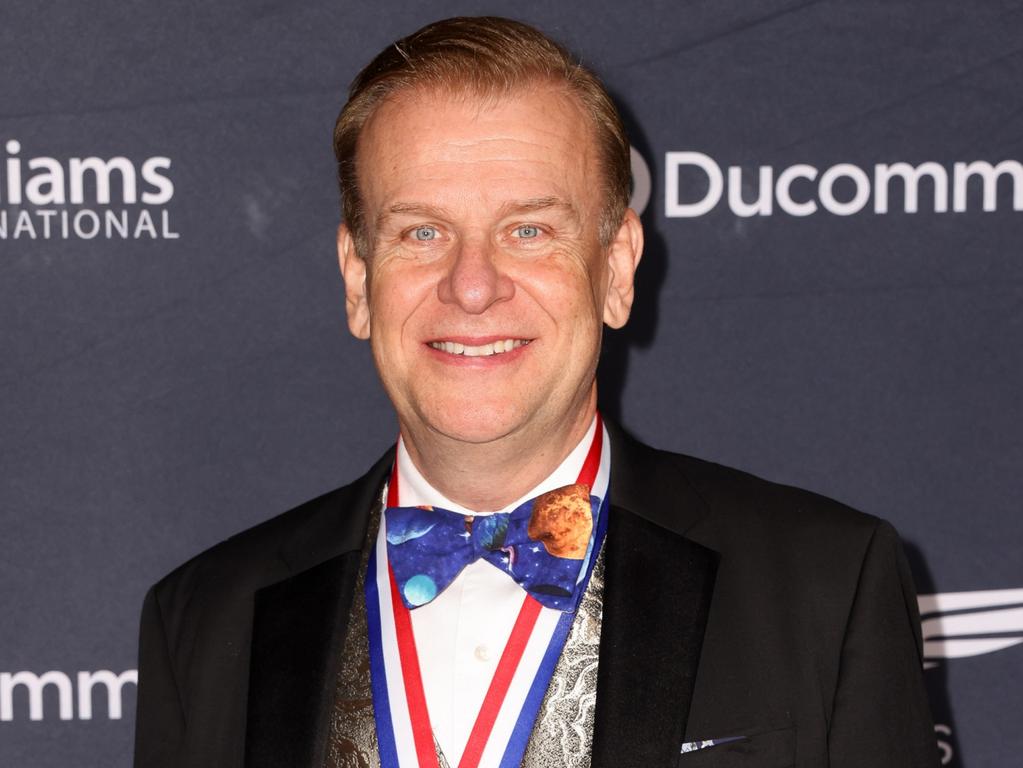

Innovator or maverick? One man will be blamed for Titan disaster – OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush

Stockton Rush saw himself as an oceanic Captain Kirk; willing to risk all to explore the planet’s last frontier. But he cast safety aside. In many ways, his is a chronicle of disaster foretold.

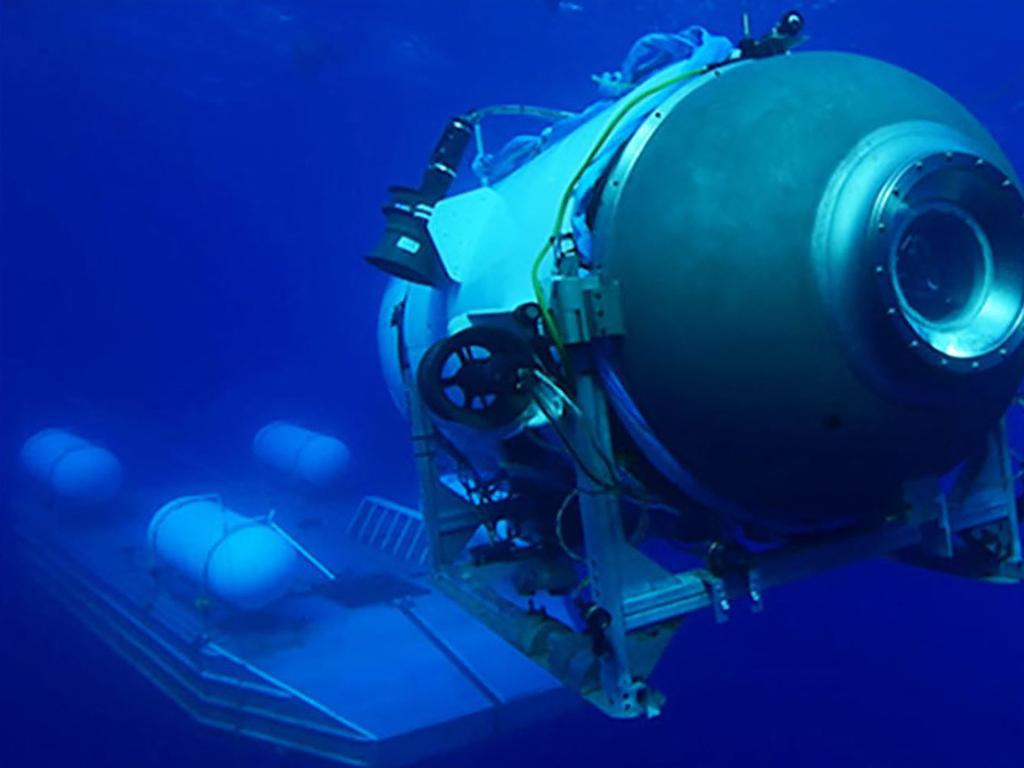

A difficult week has ended in unspeakable tragedy, with OceanGate Expedition’s Titan submersible confirmed lost in the early hours of Friday morning (AEST), after a catastrophic implosion less than two hours into its voyage to the Titanic.

Recriminations have already begun, amid calls for tighter regulation of this commercial field of oceanic exploration; with just one person at the centre of blame for the calamity that took place in one of the darkest, coldest, most inhospitable regions of the North Atlantic.

In many ways, his is the chronicle of a disaster foretold.

Stockton Rush, 61, the founder and chief executive of OceanGate Expeditions and one of the victims of the Titan disaster, was a passionate entrepreneur who saw himself as a modern-day Jacques Cousteau or even a kind of oceanic Captain Kirk; one of the few men in this world willing to risk all to explore the planet’s last frontier – the deepest reaches of the ocean.

In an ironic twist, he has familial connections to the Titanic; his wife Wendy’s great great grand parents, Isidor Straus - the owner of Macy’s department store, and his wife Ida were two of the Titanic’s 1500 victims.

But his enthusiasm for breaking boundaries turned him from an inspirational entrepreneur to a maverick, willing to forgo safety standards in his drive to reach farther than anyone before him dared to go.

Killed along with Rush was experienced French oceanographer Paul-Henri Nargeolet – one of the OceanGate team – and British billionaire Hamish Harding, UK-based businessman Shahzada Dawood and his teenage son, Suleman, who paid up to $US250,000 ($369,660) each for the thrill of the ride.

Titan, in which Rush was the pilot on its current expedition, almost certainly imploded on Sunday evening (AEST) either at the time of or shortly after losing contact with its mothership, the Polar Prince, one hour and 45 minutes into its dive to the wreck of the Titanic. The crew, mercifully, would have died instantly.

Oceanographic and submarine experts, while devastated, aren’t surprised the tragedy happened.

“It makes me angry,” retired navy commander Frank Owen tells Inquirer. Owen, a former director of the Australian submarine escape and rescue project, says it is almost certain that the material used for the hull – carbon fibre – caused the implosion.

“This is a failure of the hull,” he says. “Nothing else. They used strain gauging sensors to measure the strains on the hull and give them warning of failure. But when carbon fibre is failing at 3,800 metres that system gives them no notice; it would show 20 milliseconds before failure.

“Carbon fibre doesn’t give any indication it’s going to fail until it does,” he says, adding: “I’m a risk taker but I would have been very cautious about going on board this vessel.”

Owen, along with most other experts, is scathing of Rush’s cavalier habit of sacrificing safety for, as the OceanGate CEO described it, “pushing innovation” – an attitude they believe probably contributed to Titan’s failure.

“He deliberately decided not to use the conventional way of licensing the vehicle because it ‘gets in the way’,” Owen says, referencing the 2018 decision by OceanGate to reject an industry standard safety certification for the Titan, on the basis it would slow down the innovation process.

While the first three submersibles that OceanGate developed have gone on dozens of dives without incident, Titan, their fourth and most sophisticated sub, has been mired in controversy and litigation almost from the start.

In 2018, Rush sacked his marine director, David Lochridge, after the experienced oceanographer raised warnings about serious flaws in the Titan.

In a chilling prediction of what was to come, Lochridge’s concerns outlined in a devastating report included fears that “visible flaws” in the carbon fibre hull raised the risk of small flaws expanding into larger tears; that hazardous flammable material was being used in the craft; and that – as Owen has said – the acoustic systems installed to detect serious flaws in the submersible would show only at point of failure.

Court papers filed in 2018 state that the system “would only show when a component is about to fail – often milliseconds before an implosion – and would not detect any existing flaws prior to putting pressure onto the hull”.

That same year, the Marine Technology Society wrote to Rush outlining the risks the company was taking over safety, warning the company’s “current experimental approach” could result in “catastrophic outcomes”. MTS president Will Kohnen told CNN that if the company had certified the Titan, “some of this may have been avoided”.

“There are 10 submarines in the world that can go 12,000 feet and deeper,” Kohnen said. “All of them are certified except the Oceangate submersible.”

In a 2019 blog post defending his decision not to certify the sub, Rush wrote that classifying innovative designs often requires multiyear approval process “which gets in the way of rapid innovation” – an argument Owen refutes. The submarine expert, who worked on the development of Australia’s Remora rescue sub, says the process takes weeks at most.

Alfred Scott McLaren, a retired US Navy submariner who has twice dived on submersibles to view the Titanic, also believes the Titan’s design raised “structural concerns”, because as well as carbon fibre, the hull was made with titanium. “They have different coefficients of expansion and compression, and that works against keeping a watertight bond,” he told the New York Times.

“I’ve had three people ask me about making a dive on (Titan). And I said, ‘Don’t do it.’ I wouldn’t do it in a million years,” he said.

Chris White, manager of Autonomous Systems at the Australian Maritime College in Launceston and an expert in submersibles, agrees the blend of titanium and carbon-fibre could be a weak point if the materials weren’t solidly joined - as happens in Australian navy remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). He also says the brittleness of carbon fibre makes it risky under pressure.

"Once carbon fibre deforms it’s gone,” he says. “Even at surface atmosphere it cracks and breaks. And when it’s gone, it’s gone.”

He points out that the fact the tail cone and the braking skids had not shattered indicated they weren’t part of the pressure loss and were probably made of different materials.

Bart Kemper, principal engineer with Kemper Engineering Services in Louisiana, describes the development of Titan as “experimental with no oversight”, which is not typical of industry practice.

“These are literally the things that keep us up at night because we don’t want to be responsible for one of these stories,” Kemper told the Toronto Sun.

Rush, 61, graduated from Princeton in 1984 with a degree in aerospace engineering, before working as a flight test engineer of the F-15 program. His poor eyesight meant the end of his dream to become an astronaut, and after Richard Branson launched the first commercial aircraft into space he had an “epiphany.”

“I had this epiphany that this was not at all what I wanted to do,” Rush told the Smithsonian magazine. “I didn’t want to go up into space as a tourist. I wanted to be Captain Kirk on the Enterprise. I wanted to explore.”

He founded OceanGate in 2009, in part to bring rich thrillseekers to historic wreck sites but also to help scientists and researchers unravel the mysteries of the ocean by offering better access to the sea floor.

He frequently boasted of “breaking rules” in the construction of the Titan. In an interview with a Mexican blogger last year, he boasted: “I’d like to be remembered as an innovator. I think it was General MacArthur who said, ‘You’re remembered for the rules you break’ and you know I’ve broken some rules to make this.”

He told journalist David Pogue in an interview last year: “At some point, safety just is pure waste.

“I mean, if you just want to be safe, don’t get out of bed. Don’t get in your car. Don’t do anything.” Pogue joined an expedition to the Titanic but it ended after just 35 minutes after mechanical failure.

In another interview Rush derided the industry’s “obscenely safe” regulatory process, insisting, again, it stood in the way of innovation.

A German thrill seeker who travelled on a Titan expedition in 2021 described it as a “suicide mission.” Arthur Loibl told Bild newspaper: “The first submarine didn’t work, then a dive at 1,600 meters had to be abandoned. “My mission was the fifth, but we also went into the water five hours late due to electrical problems.”

White is cautious about blaming Rush for the tragedy, but he points out the difference between Rush’s apparently lax safety measures and those far tighter procedures taught to navy personnel at the Australian Maritime College.

“We have a robust set of procedures that have three levels of back ups and different ways of powering things in the vessel,” he says. “So if all else fails you still have back up.”

Rush’s ‘innovation over caution’ attitude was tellingly revealed in a conversation with a representative at Teledyne Marine, a marine technology company, in 2020. Rush told the rep he didn’t want to hire “ex-military submariners … 50-year-old white guys,” preferring “younger, more inspirational” staff.

“The older white guys are the ones who would have seen the bumps in the road,” Owen, an ex-military submariner points out. “Otherwise it’s all bright ideas, no substance.”

Owen says Rush’s egoism and carelessness with safety was demonstrated by his decision to pilot Titan himself on this last dive, although he was by no means the best or most qualified person on the team for that job. “He probably wanted to impress the rich guests,” he says disparagingly. “Hoped they’d put money into his venture. But controlling a submersible is much harder than just pushing the controls of an X-box.”

The passengers on board the last, fatal descent, were required to sign a waiver that might have suggested to them the danger in which they were placing themselves. They were asked to accept that the sub “has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body, and could result in physical injury, disability, emotional trauma or death”.

In a haunting reminder of history, James Cameron, the filmmaker of the blockbuster movie Titanic, and a builder of deep sea submersibles, says he’s struck by the similarity of the disaster with the Titanic sinking in 1912, when the captain ignored repeated warnings about ice only to steam full speed into an ice field on a moonless night.

“This is a similar tragedy at the same exact site,” he told ABC America. “It is astonishing, quite surreal.’’

Will this be the end of commercial deep sea exploration? White and Owen believe not, although they are optimistic that the Titan will provide the lessons in bad judgement that others can learn from.

White would like to see commercial exploration pause until those lessons are learned. “Let’s stop and learn from this,” he says. “Exploration of the ocean, this frontier, should continue, but let’s make things safer.”

Owen agrees. “Tighter regulation will happen,” he says “but there will always be people who want to explore the deepest ocean, to understand the seabed, an area less explored than space”. “There will be more journeys.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout