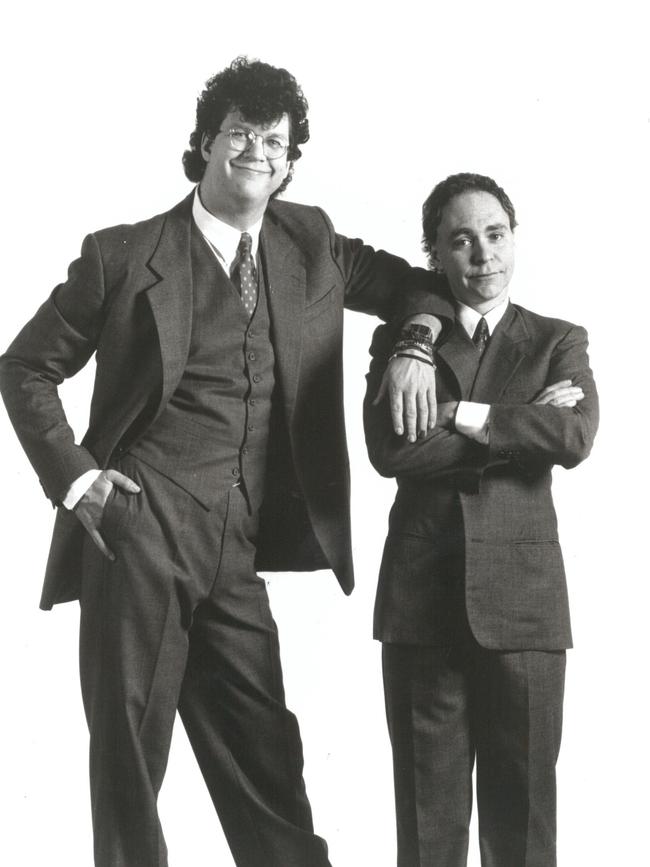

Interview: Penn and Teller on the secret of all magic ahead of 2022 Australian tour

Ahead of an Australian tour, the acclaimed American illusionists reveal how their very best tricks create a sense of inner turmoil | WATCH

Magic, when done well, opens a window on to a world where cause and effect are not bound by physics. A great magic trick tells us a beautiful lie, and the very best tricks create a sense of inner turmoil, where you know what you’re seeing can’t possibly be happening – yet still, some part of you hopes, even believes, that it is.

The American performers Penn and Teller have been telling beautiful lies and creating inner turmoil in audiences since they joined forces in 1975. During that time, they have become two of the best-known magicians in the world, thanks to a string of pop-culture appearances across the decades.

To international audiences today, they might be best known for their chief roles on the TV series Penn & Teller: Fool Us – recently renewed for its ninth season – where a cast of up-and-comers and magic veterans do their best to trick the near-untrickable pair. Those successful few tricksters win the opportunity to perform at The Rio in Las Vegas, where the duo has a long-running residency.

Through it all, 67-year-old Penn Jillette and Teller, 74 – who long ago legally dropped his given name, Raymond, deeming it needless clutter – have continued to develop clever illusions, crafty moves and sleights of hand that dazzle our eyes and tickle our brains.

In their act, Penn is the tall, talkative one; Teller on stage is non-verbal, relying instead on his hands, body and face to do the talking. Among a sea of mind-bending material, one of their most fascinating works centres on a couple of props, and is introduced by Penn with only a few words before he walks off stage. “The next trick is done with a piece of string,” he says, before ceding our attention to Teller.

The mute man carries a wooden hoop and a red ball similar in size to a soccer ball. First, he hands both objects to an audience member in the front row, who verifies that they look and feel normal, although the very notion of “normal” will soon become as malleable as playdough.

The red ball appears to roll back and forth along a park bench at Teller’s command, while the conductor stands at a remove. As he sits on the bench and edges away from it, the ball somehow follows him like a lost, legless dog looking for a new master.

At one point, it becomes stuck to the seat of his pants, and when he directs the ball to jump through the hoop, it eventually obeys, although not without a touch of adolescent disobedience.

After a final hoop jump and a round of applause, Penn walks back on to the stage with a pair of scissors. Finally, Teller holds the ball vertically by a string, which he passes to his partner, who makes a show of cutting the connection before booting the freed ball up into the lighting fixtures.

The above description scarcely does justice to the strangely emotional feeling of watching all of this unfold; you can easily find on YouTube a version of the trick, albeit one performed for television cameras rather than on stage inside a darkened theatre filled with curious minds sharing bated breath.

If you’re wondering how it was done, you’re asking the wrong question, because Penn already told you, didn’t he? “The next trick is done with a piece of string,” he said. Or was he telling you a beautiful lie?

Asked about what he feels when he watches Teller with the red ball, Penn speaks slowly, pausing between each sentence. “It is one of Teller’s best bits,” he tells Review. “It’s one of the bits people like the most. It’s one of the bits magicians like the most. I think it’s really, really good. I don’t like it.”

After this last sentence, he bursts out laughing, as Penn tends to do regularly. His laugh is gleeful, somewhere between a giggle and a cackle, and it is infectious: after hearing it once, you want to hear it again.

Why doesn’t Penn like Teller’s red ball trick? We’ll come to that. Here’s a better question than asking how it was done, though: how much time did Teller invest into performing this one illusion, which takes all of four minutes from first words to final cut?

You might admire the red ball trick and think that you’d be willing to spend 10 hours learning how to do it. Your best friend might think that learning to do that trick in 10 hours is simply impossible, so therefore, its very existence is a miracle.

“What you haven’t even considered,” says Penn, “is the fact that someone in the world would think that was worth 500 hours. You’ve never even considered that, because it’s not worth that; it’s the fact that we have a distorted image of how long we’re willing to work on something that’s just a couple of minutes to you.”

And that right there, says Penn, is the secret at the heart of their art: sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect.

-

At the age of five, Teller contracted a viral infection that nearly killed him. While recuperating, he watched the US children’s TV program Howdy Doody, and one of his favourite characters was Clarabell, a mute clown who expressed himself entirely through mime and magic tricks.

When the young boy sent in a mail order for a Howdy Doody magic kit, he found that his favourite item was a small box built to contain three miniature chocolate bars. After the budding magician showed them to his audience, then shook the box and reopened it, only one chocolate would reappear.

Teller was astonished by the effect that performing with the magic box had on his parents, friends and family members. For the first time, he was struck by the notion that something he could do with his own hands could be both a miracle, and a trick. That these two things could coexist – what was real, and what wasn’t – at the same time, in the same action? That paradox dug deep into his brain, like a weed – one whose growth remains untrammelled today.

Penn Jillette was less interested in magic as a child, and instead became a serious student of juggling – although as he likes to note, under the Dewey decimal system at your local library, magic and juggling are grouped very close together under the “arts nobody really cares about”, alongside ventriloquism and mime.

As a young street performance artist in Philadelphia, Penn ensured he was scrupulously well-dressed: by wearing a $3000 watch and looking the very opposite of needy, he hoped to convey the idea that anyone should be ashamed to offer him less than a $20 bill after watching his act.

At the time, Penn was a great juggler, but he was even greater at drawing a crowd by literally creating a scene from nothing. Within minutes, he and his carnival-barker voice could attract a hundreds-strong audience. Once his comparatively brief juggling act was done, he would yell something like, “You people in the very back row, you didn’t get to see any of the show. I don’t expect any money from you, that would be foolish – but I do expect you to hold hands and let nobody out who has not given me money. You people are now my theatre.”

By developing a unique meta commentary on performance art, Penn became an adept. He quickly became wealthy, too, often earning thousands of dollars in cash per week, a feat that bamboozled his accountant, who wrongly assumed the lifetime teetotaller must be a drug dealer.

Teller had spent six years as a high school Latin teacher by the time he watched Penn one day, delivering what he once described as “the tightest and most magnificent 12 minutes that anyone had ever seen on the street”.

The teacher had just been given tenure, but the overly confident younger man pestered the part-time magician enough to take a one-year leave of absence. First working together as a trio with a mutual friend, Weir Chrisemer, for about a thousand performances – then ultimately, as Penn & Teller, from 1981 onwards – their combination of talents and perspectives resulted in something unique, from off-Broadway, to Broadway, to Vegas and beyond.

“For the first six years we worked together, we were always sort of suspicious and in conflict,” Teller tells Review. “But eventually, we began to really see tremendous value in being two such different people, pulling always in two different directions, towards the same work of art.”

-

Though they have now clocked 41 years and many thousands of shows together, from the beginning, their whole aesthetic as a double act has revolved around a simple question: what would they like to see on stage if they were sitting in the audience?

“We’ve always been interested in the difference between what you see and what you know,” says Teller. “That’s where the real spark of magic happens for an audience: they see something, and they fully estimate what they think is going on – and then they realise that that’s completely contrary to what they know could possibly go on. When those two things hit against each other, like steel and flint, there’s this spark.

“It’s not altogether comfortable; that’s one of the fine features of magic, and one of the fine features of almost every bit of entertainment that I like: you’re always a little uneasy; you’re always a little suspicious. That quality is a very powerful element of the form that we work in.”

If you have only ever seen them on television, you probably have not heard the shorter, older man speak, so it may come as a surprise to learn that Teller’s voice is lively, certain and commanding.

He has a gift for speaking in beautiful, flowing, fully formed paragraphs, and his active mind is prone to wild diversions that open dozens of potential conversational doors. “Do you know how you die from crucifixion?” he asks me at one point, in a long answer to a question that begins with the magic kit he obtained at age five, and how that discovery has informed what became his life’s work. (Answer: you become so exhausted that you are gradually strangled by your own weight.)

When Review speaks with both men in separate video interviews conducted in mid-April, ahead of a long-planned, Covid-delayed Australian visit, they are about to start filming the new season of their TV series Fool Us, in between the four 90-minute shows they perform in Las Vegas each week at the 1500 capacity Penn & Teller Theatre.

Asked what he feels when he executes the red ball trick perfectly, Teller replies with a laugh: “Relieved. It’s very difficult. I have to admit that it’s not part of the Australian tour, because it requires things that we don’t have in all the theatres.”

He describes how, in his regular research into the annals of magic history, he found a version of the trick as recorded by a magician and inventor named David P. Abbott, wherein the ball floated.

“The effect was very popular with certain master magicians on the vaudeville circuit,” says Teller. “Everything about it is awful – except it’s great. A guy running around the stage, chasing a golden globe that’s floating in the air, and he passes a hoop over it? That’s excruciating.”

That’s part of the reason Teller’s partner did not share his captivation with Abbott’s version of the trick, as well as a fundamental difference in taste, as the younger man’s mind has never been drawn to the personification of inanimate objects.

“Initially, Penn had a problem with it, because it had no extra dimension to it,” says Teller.

“It didn’t have the intellectual dimension; it had only the romantic dimension. I changed his mind very dramatically by, instead of having the ball float, the ball is ‘alive’ – but that still wasn’t enough. Penn said, ‘That would be fine in anybody else’s show, but not really in ours’.”

“I think he was completely right,” Teller continues. “And I noticed that the people who liked that trick best were magicians, because they knew the principle of how it works. They knew that it was somehow being suspended by a piece of thread. And so I said to him, ‘Why don’t we just say, this is a trick that’s done with a piece of thread?’ At least people know where to go, because yes, it is; we’re telling the dead-level truth.”

Teller estimates that he poured 18 months into perfecting it, an investment that began with time spent in his home library, with Abbott’s ancient instructions propped on a music stand. Then at least an hour by himself after every Vegas show, and alone at a mirrored dance studio in Toronto, and at a cabin deep in the woods.

“Boy, he did work on that red ball a f..king lot,” says Penn, cackling. “The amount you think he worked on it is still way below what he worked on it.”

They’re telling the truth about the trick, but its execution is such that the human eye and brain are scrambled by turmoil. Our instinct is to fiercely reject Penn’s factual statement as a beautiful lie, for it is all but impossible for us to fathom how it could be true.

During those precious few minutes on stage, that damned ball appears to be moving of its own accord, and it’s because Teller eventually hit upon the idea of self-deception as the final dimension to his performance.

Each time he picks up that sphere, Teller doesn’t think about those hundreds of hours spent alone, just a man with a red ball, trying to make it obey, fired by a steely determination to execute something he wants to come across as both real and unreal.

Instead, he thinks to himself: I am depicting a magic trick done with a piece of thread by using a ball that is actually alive. Sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect.

Penn & Teller’s Australian tour starts at the Sydney Opera House (June 1-11), followed by the Arts Centre Melbourne (June 14-18) and QPAC, Brisbane (June 22-July 3).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout