Daniel Johns interview: ‘To be predictable is my worst nightmare’

In hindsight, cracking open the champagne was a mistake. So was chasing it with vodka during a lively afternoon with Daniel Johns.

In hindsight, cracking open the champagne was a mistake. So was chasing it with vodka. At the time, though, it felt like the right thing to do during a lively afternoon with one of Australia’s greatest rock stars at his palatial, art-packed home near Newcastle, NSW. Interviews with Daniel Johns have been exceedingly rare since the singer-songwriter’s world-famous band Silverchair disbanded in 2011. So when he offered to share a few quiet drinks on his rooftop on a weekday afternoon, with the wide arc of the Pacific Ocean before us and the warm March sun at our backs, the answer was yes. Who could resist?

Once we’d climbed the ladder up to the roof he flipped the switch to performer, playfully shooshed his girlfriend and said with a smile, “We’re actually doing a serious interview. All right, do you want to ask more questions? Let’s do it.” With a mind as active as his, the conversational possibilities stretched beyond the rain we watched falling out at sea and the rainbow that arced at the edge of our view. Yet at several points he asked if he was being dull. Perhaps this was his insecurity speaking; there is little chance of boredom when in his company. “I do not want to live a boring life,” he said emphatically. “I want to live inspired, and I want to make amazing art and amazing music. And I want people who come to my compound – including you – to have a nice time.”

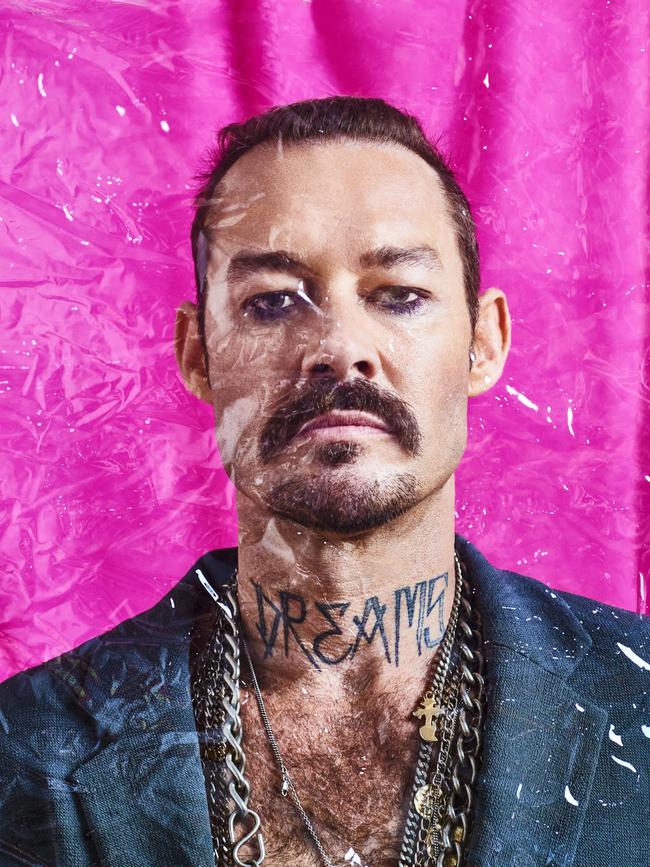

On that sunny Tuesday in mid-March, ahead of the release of his second solo album – a surprising and ambitious set that might up-end everything you think you know about his music – Johns presented as happy, healthy and as open to journalistic inquiry as possible. “I’m telling you the truth, and it’s my job to tell the truth,” he assured me.

When he opened the fridge and offered a drink it didn’t ring alarm bells; it would have been unremarkable if not for what happened later. But looks and words can be deceiving, just as well-rehearsed masks and personas can obscure what lies beneath. Nine days later, Johns crashed his car while drink-driving near Newcastle – he veered to the wrong side of the road into an oncoming van. The driver of the other vehicle was treated at the scene and his passenger was taken to hospital for treatment. Johns was uninjured but a breath test revealed a blood alcohol reading of 0.157, more than three times the legal limit.

“As you know, my mental health is a work in progress,” Johns wrote to his 100,000 followers on Instagram after the accident. “I have good days and bad days but it’s something I always have to manage. Over the last week I began to experience panic attacks. Last night I got lost while driving and I was in an accident.”

“I am OK, everyone is OK,” he wrote on March 24. “Alongside my therapy, I’ve been self-medicating with alcohol to deal with my PTSD, anxiety and depression. I know this is not sustainable or healthy. I have to step back now as I’m self-admitting to a rehabilitation centre and I don’t know how long I’ll be there.”

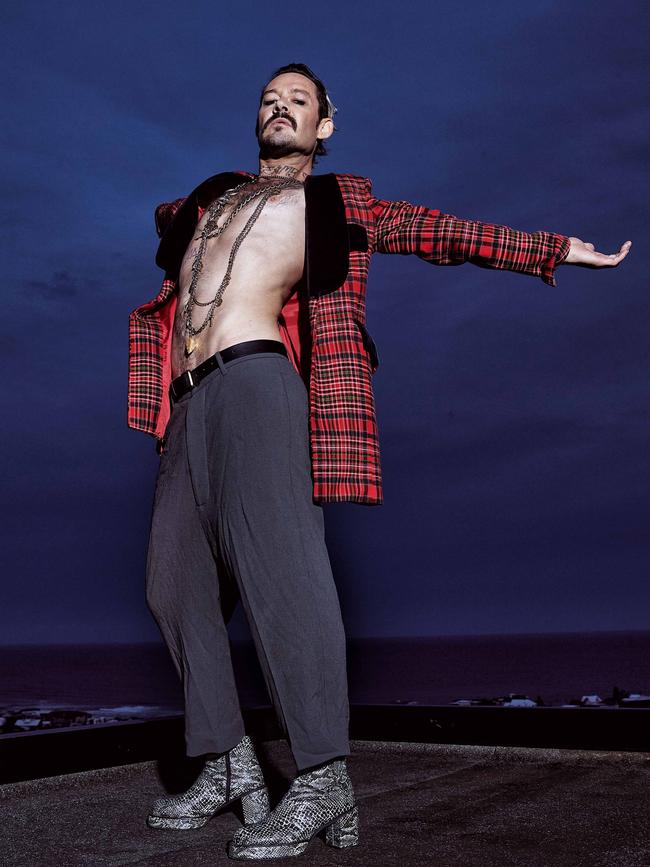

He’s just turned 43, meaning Johns has spent almost 30 years in the fierce glare of the spotlight, first as a teenage rock star and later as a tabloid paparazzi magnet after marrying pop singer Natalie Imbruglia in 2003 (they separated in 2008). He’s learnt to poke fun at this unwanted attention: when we meet, the bold font on his grey singlet reads, in capital letters: Nobody knows I work for the Daily Mail.

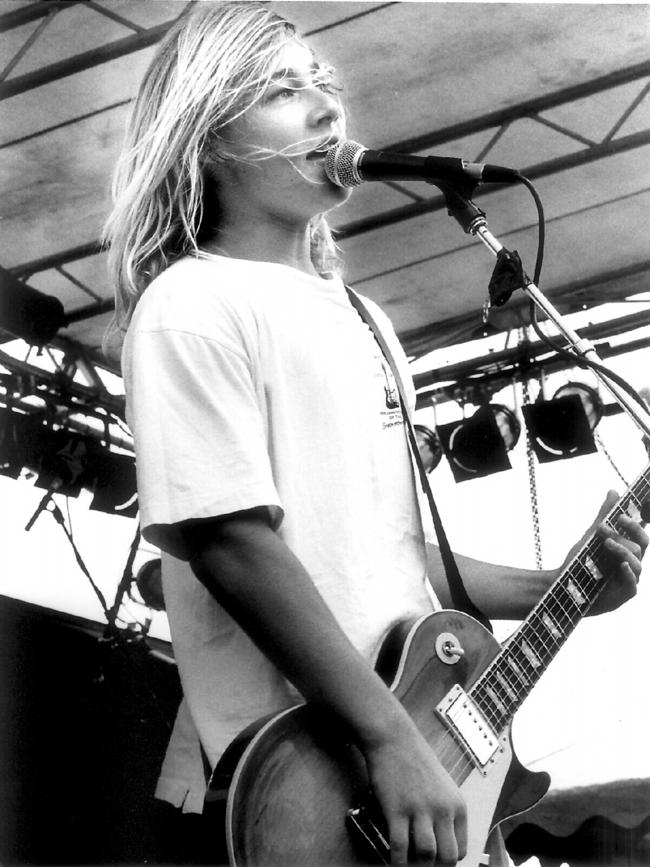

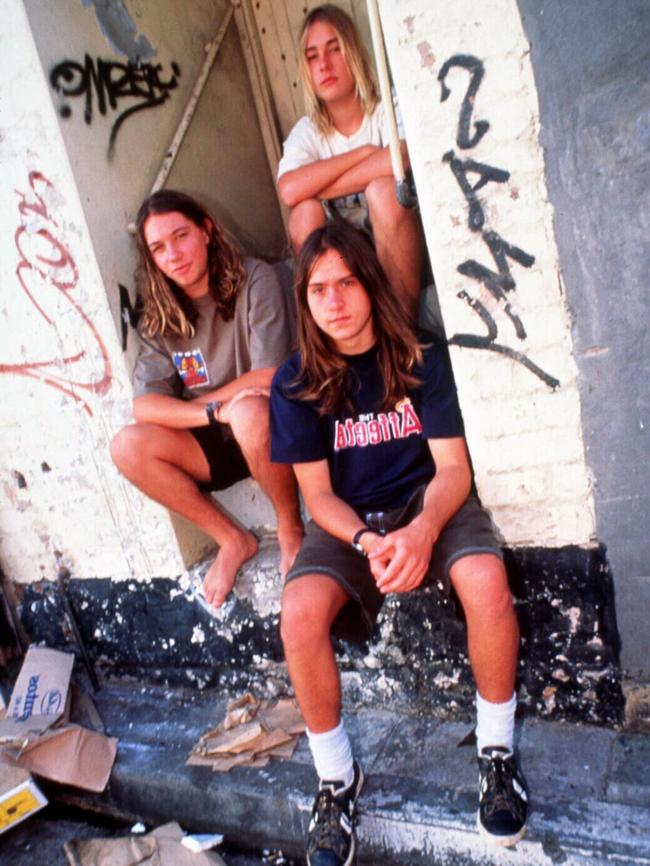

For most of his life, though, his image has been bought and sold by entities beyond his control; his story told time and again with little agency on his part. Once, millions of fans around the world thrilled to the alternative rock sounds created by singer/guitarist Johns, drummer Ben Gillies and bassist Chris Joannou – three teenagers from Newcastle who were 15 years old when they recorded the songs comprising Silverchair’s 1995 debut, Frogstomp. But as his fame grew, Johns essentially lost himself.

That’s why Who is Daniel Johns?, a five-part documentary podcast published on streaming platform Spotify last year, was so important to him. “I got to speak the truth without throwing anyone under the bus,” he says, choosing his words carefully. “There’s been a very disengaged and irrelevant interpretation of what’s happened in my life; I’ve let the powers-that-be tell my narrative.” He says he was able to tell the truth “without feeling like I was a rat”, adding: “Believe me, I could have said some shit that would have f..ked some people up. But I just thought I’d take the high road. All I want to do is tell the truth, without the bad bits – because the bad bits you can hear in the music.”

The podcast thrust Johns’ artistry back toward the centre of popular culture for perhaps the first time since Silverchair’s last hit song, the 2007 chart-topping single Straight Lines. Above all, it offered a compelling portrait of the corrosive effects of fame on a young star. Fame contorted his body like a funhouse mirror, resulting in the eating disorder anorexia nervosa, which he wrote about in the 1999 single Ana’s Song (Open Fire). It distorted his mind in dangerously self-destructive ways with which he’s still coming to terms, although he was bold enough at the time to become one of the few famous Australian males willing to discuss his mental struggles publicly.

There’s a song about all of this on his new album, naturally enough. Titled FreakNever, it begins with a creepy, ocker choir of kids’ voices singing the opening lyrics to Silverchair’s 1997 hit Freak as if jumping rope in a playground. The verse begins:

No more maybes

The world stole a baby

Took his soul on tour and

Made a deal with devil

He didn’t want to be different

But fame’s a disease

What if the FutureNever happened?

Would you ever believe?

A young girl – a close family friend, credited under the name Purplegirl – sings these words, sweetly and plaintively. Three minutes in, the song briefly breaks into Freak’s grinding signature riff for a few bars before fading away to conclude with a reprise of the sing-song children’s choir. It’s an extraordinary juncture between Johns’ teenage past and the unknown future; somewhere between a sequel and a signpost to what’s ahead.

Johns’ father Greg is an ardent music fan who ran a fruit stall in Newcastle, two hours’ drive north of Sydney, while his mum Julie raised the family. The eldest of three children, Daniel vividly recalls the first guitar-based album that made him want to be in a band: Deep Purple In Rock. When he got his first electric guitar as a child, the first riff he learnt to play by ear was Money For Nothing by Dire Straits. “I remember my dad came into the bedroom and was like, ‘How did you learn that?’” he says. “I saw the smile on my dad’s face and it made me want to play guitar even more. And then my mum was kind of impressed, and that was the beginning of writing Frogstomp: ‘Shit, my parents think I’m kind of all right!’ ” They weren’t the only ones. The three Silverchair teenagers wrote, recorded and toured in a constant cycle for several years while continuing their high school studies.

Johns bought this house in 2000 after coming off tour for the band’s third album Neon Ballroom. It’s located on a quiet street in the same coastal suburb where he grew up, but he now has a much better view. From his vantage point cut into a cliff, in a huge house containing a squash court with viewing platform – although the singer doesn’t play – Johns holed himself up for much of 2000, rarely leaving his bunker, opting for isolation two decades before the rest of us got a taste of it.

It was here that he learnt to play the piano on which he wrote Silverchair’s 2002 masterpiece Diorama. He wrote the lead single The Greatest View while looking out the front window down the hill, toward his parents’ house. I’m watching you watch over me / And I’ve got the greatest view from here, he sang in its chorus. Asked about what his parents mean to him, Johns takes the longest pause during six hours of conversation and frivolity. “I know without my family’s support, I would have gone heavily off the rails,” he says eventually. “It was their belief in me that made me not do that. There’s been times where I’ve been that close,” he says, holding up his index finger and thumb to indicate a tiny gap. “I could have gone really bad. I’ve been to a lot of institutions; I was suicidal when I was younger. I just couldn’t deal with it, and they just kept believing in me and believing in me.

“My brother, my sister – my family’s so f..kin’ tight. I’m unbelievably grateful, because some of the shit that I’ve done, most people would have gone, ‘You’re a f..king disaster’,” he says, laughing. “It’s true, man. I’ve put them through hell, and they’ve never backed away. They were always supportive. That’s f..king rare. I’ve had friends back away, but my family’s always been like, ‘No, we’ve got you – you can do it.’” (His parents declined to speak with me for this story – but I later learn that those close to him have been worried about him for some time.)

Their belief, says Johns, “made me want to impress them, and it comes back to when I played Money For Nothing and I saw my dad smile. It made me want to get better. And then when I saw my family, no matter what I put them through, they were just there? That made me want to be better.”

Structurally speaking, little has changed in this house since Johns bought it at age 21. Sonically, though, this sprawling living room has been filled with his life’s work as an adult songwriter. The black Yamaha piano still sits in the front corner, near the entrance and behind the dense green hedge that shields him from prying eyes. A drum kit, guitars, bass and keyboards are all within easy reach.

The classic Nas hip-hop album Illmatic is playing softly on the stereo on my arrival; small photos of Tom Waits, Keith Richards and Jimi Hendrix hang above his television, while a large portrait of the wired eyes of Ian Curtis – the Joy Division singer who died at age 23 – is stored downstairs, the image deemed too creepy and morbid for Johns’ bedroom.

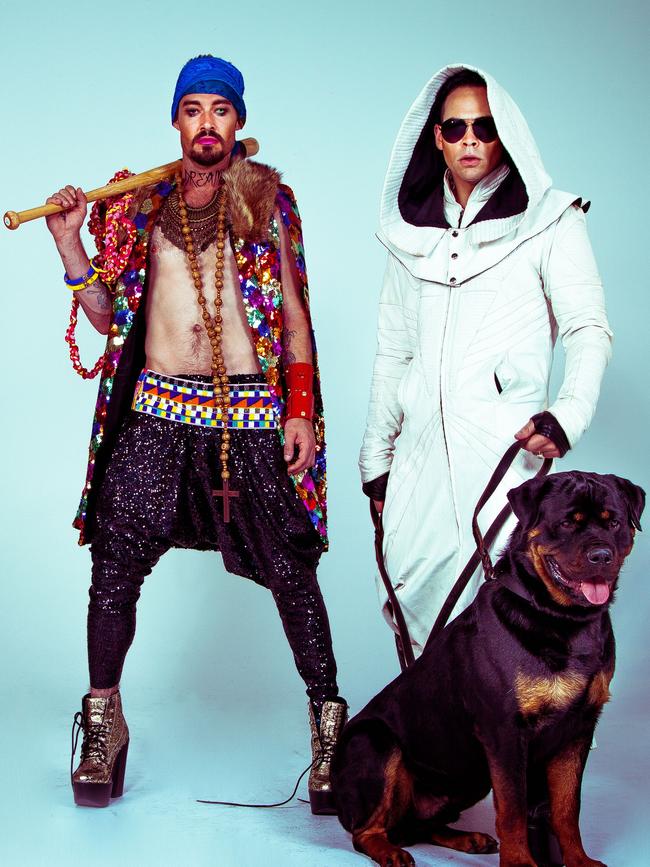

Since Silverchair’s final album Young Modern was released in 2007, and the band played its final shows together in 2010, his musical output has been slim: after releasing a solo album rooted in R & B and electronic music in 2015, he arranged the soundtrack for the children’s animated series Beat Bugs in 2016, and issued a collaborative album with Empire of the Sun frontman Luke Steele in 2018 under the moniker Dreams.

None of these projects set the world on fire, commercially speaking. Johns hasn’t had a hit song in 15 years, since Straight Lines in 2007. Performances have been few and far between, too. His last live appearance was at Laneway Festival in 2019, where he emerged from a coffin during a set by friend Chris Emerson – aka Sydney electronic musician What So Not – to play a scorching version of Freak.

Ahead of my visit, I had been listening to his new album FutureNever on repeat, and greatly enjoying it. The 12 tracks are by turns surprising, dramatic, cinematic and more than a little show-offy. The arrangements touch on pop, rock, classical and electronic music, while his vocal performances are stunning.

By far Johns’ most diverse and creatively expansive work, it almost never saw the light of day. After his debut solo album Talk, he felt spent. “I really, really tried so hard to prove myself outside of being ‘the guy from Silverchair’,” he says from his couch. “It wasn’t a failure, but I didn’t feel like it had any support. Sometimes I get sentimental when I’m sitting at home by myself at four in the morning and I go, ‘I’m gonna put on Talk.’ I don’t have any moment where I go, ‘F..k, I shouldn’t have done that’ – and that’s one of the first records in my whole career where I still love it.”

Given the close-knit ties between himself and his two siblings, it’s fitting that it was his younger brother Heath who talked him into releasing new work. Heath has stuck like glue to Daniel all the way through. At the Silverchair frontman’s most challenging moments – when he was bed-bound and in debilitating pain from a mysterious illness that also crippled the band’s ability to tour Diorama – it was Heath who stayed up late with him, watching music videos on Channel V together in their parents’ house.

That period from two decades ago still rankles. The band’s US label, Atlantic Records, was unhappy with the bold creative leap Johns had taken in his pop songwriting. Feeling it was out of step with the alt-rock and nu-metal that was popular at the time, Atlantic shelved the album in the US and the stress from losing control of his masterpiece had dire consequences; Johns succumbed to reactive arthritis. He had no choice but to put everything on hold to recover from the all-consuming illness for 12 months or so.

The band’s management retained the Australian release rights to Diorama, but touring in 2002 was limited to a handful of shows here and in New Zealand. Pressing pause on the machinery surrounding Silverchair at that time left Johns feeling like a cash cow who’d lost the ability to produce milk. It widened a sense of alienation between the band members that had begun during their teen years when the singer-songwriter was cooped up at home, clinically depressed, feeling the pressures of media intrusions, stalkers, fans hassling his family and hand-delivering suicide notes – all while Gillies and Joannou were able to live reasonably normal lives largely free from scrutiny.

The band has been on “indefinite hiatus” since May 2011, when the musicians noted in a statement that “we stand by the same rules now as we did back then… if the band stops being fun and if it’s no longer fulfilling creatively, then we need to stop”. Friends since they were seven, the three former bandmates don’t talk much anymore; Johns likens the relationship nowadays to a divorce. “We’ve never really healed, but I don’t dislike them, and they don’t dislike me, I don’t think,” he said on the podcast. “But it’s just really awkward, and it’s hard to mend that bridge.”

In 2016 Johns was ready to retire from public view, having taken a significant creative risk that didn’t really pay off. “After Talk, I was like, ‘I don’t want to do music anymore, it’s just not worth it. I put too much effort in and I get nothing in return.’ I just felt like it was a waste of time. I’ve got a house, I’ve got a girl, I’ve got a dog, I’ve got a car… I’ve got a squash court,” he says, laughing. “I don’t really need anything. I’m just going to paint. ”

Johns has a private online folder of unreleased music and while sifting through it one day, Heath – who is the managing director of record label BMG Australia – had a revelation. The songwriter’s mindset at the time was that he wrote music anyway, every day; he didn’t need other people to hear it. “But Heath was the one that was like, ‘No, dude – this is your best shit’,” says Johns. “I had no idea, ’cause I was totally checked out. I thought it was just nothing.” Now he agrees with Heath. “I love this record. I honestly think it’s the best thing I’ve ever done.”

Nobody knows whether fans will flock to his new album like they did with Frogstomp or scratch their heads and edge away, as most did with Talk. “I don’t give a f..k what people think – I know it’s good,” says Johns. “Sometimes I find the general public so stupid – but most of the time, I think the general public is way smarter than record companies give them credit for. Most people who are interested in art and music, they want to be challenged; they don’t just want meat and potatoes. Sometimes you just want a side of seaweed with sesame seeds and ponzu sauce; something to intrigue your palate.”

Then he cracks up, breaking the spell on an otherwise serious discussion about the meeting between art and commerce. “Shittest metaphor ever, but you know what I mean?” he says, laughing. “I was trying to be funny. I really think people underestimate people’s appetite to be at the very least intrigued. To be predictable is my worst nightmare.”

While discussing the podcast – which was produced by journalists Kaitlyn Sawrey and Frank Lopez – Johns is clearly proud that his life story briefly outcharted the massively popular Joe Rogan Experience, which Spotify bought the exclusive rights for in 2020. “I tell everyone I beat Joe Rogan in Australia, and Canada as well,” he says. “I just like people thinking that, because you know how Joe Rogan got, like, $240 million? I didn’t even get close to that. I think I got like $100,000 – which paid for the leak in my kitchen roof. I didn’t get that sweet Spotify money.”

In the meantime, his girlfriend – who Johns asked me not to name – has ordered another bottle of champagne to be delivered to his compound. We’re talking about the path that led him here to this big house overlooking the coast, and all the music he’s written downstairs. “I feel like I’m being very vain, and this is why I hate doing interviews, because when I tell the truth, it feels like I’m arrogant, and I’m not,” he says. “I’m actually very insecure. I still think I’m a bit crap. I still think I’m not at the level I want to be.”

Although his public output has been slim, the 12 tracks on FutureNever form the tip of the iceberg – he has hundreds more finished songs in the vault that may not see the light of day. “I just want to be the best songwriter in the world that’s ever happened, and I’m not scared of saying that,” he says, as his eyes trace the descent of a distant hang-glider. “That’s not saying I am – it’s a desire. Most people would just rest on their laurels. I don’t have laurels, and I don’t rest.”

By now, the sun is drawing closer to the horizon and the rainbows are a distant memory. “Let’s go and listen to the record downstairs,” says Johns. “Let’s listen to the record really loud.” After carefully navigating the ladder back to earth, we retreat to his living room, where Johns plays the ornate album opener Reclaim Your Heart at a volume that leaves my ears ringing, as if I’m at a rock concert. After a few tracks and a few more sips, he opens the vault. “Can I play you something that no one’s ever heard?” he asks, before pumping out the first of several unreleased pop bangers. It might be the vodka talking, but they’re just as good as anything on FutureNever. When I express my shock that they were left off, he waves away the compliment. “Next album,” he says.

Although Johns says he’s long been obsessed with the sound of “things about to break” – amplifier feedback and guitar noise among them – none of us know then that nine days later, his life will break in a major way when he crashes his car into an oncoming van while drunk. He checks himself into a long stint in rehab and via his lawyer pleads guilty to high-range drink-driving – an offence that could carry a jail sentence.

Australia’s greatest living rock star is back in the headlines for all the wrong reasons. Perhaps the shockwaves from that incident will mean no more nights like this. No more champagne deliveries on sunny, rainbow-hued afternoons; no more pissing off his roof into the pool, as he did during our session rather than climbing back down the ladder to use the bathroom.

Ensconced in his compound, Johns seemed to have everything he needed – his music, his girl and his dog Gia. He was home. Up on that roof he’d told me he didn’t care what happened next, and I’ll never know whether that was the truth, naive bravado or something in between.

FutureNever is out now via BMG Australia. Lifeline 13 11 14

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout