How Kevin Parker’s Tame Impala conquered the world

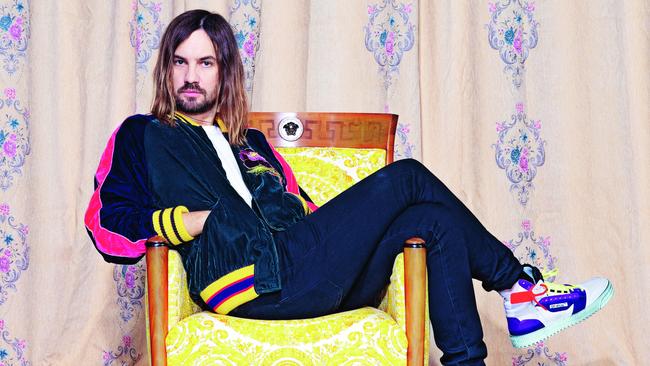

He fronts Tame Impala and is hailed as a musical genius. How did Kevin Parker take his one-man project from Fremantle to the world’s biggest stages?

When more than 100,000 music fans gathered in the Californian desert last April for the biggest event on the American popular music calendar, an Australian act was one of three headliners alongside megastars Ariana Grande and Childish Gambino. For Saturday night’s final performance at the 20th anniversary of the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, out strode Kevin Parker, the Fremantle-based singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, producer and recording engineer who embodies Tame Impala in every waking moment other than during live performances, when he is joined by four bandmates who have each been by his side for at least seven years. What began as a one-man psychedelic rock project conceived in a Perth share house has ballooned to become one of the most popular and successful Australian acts in the world.

At 10.30pm, tens of thousands of people gathered before the stage and its huge video screens, many more tuning in to a YouTube live stream. Suspended high above the five musicians was a curious, glowing centrepiece: a light-infused, smoke-belching steel ring weighing six tonnes that resembled a flying saucer. Midway through the 90-minute set, it would slowly descend to hover above the musicians’ heads, adding drama and intrigue to a laser-heavy light show set against a thumping soundtrack that skilfully blends elements of rock, pop, funk, hip-hop beats and electronic music to create something that sounds like no other act on the planet.

The high-wire nature of the production had provided plenty of cause for concern in the days leading up to the first performance. Tame Impala had never played beneath the ring before – it was essentially constructed for sole use at the festival. And during the first full production rehearsal, the saucer had descended only three-quarters of the way before high desert winds forced a pause in proceedings. As the hours ticked down to show time, nobody was sure whether the huge, expensive ornament could be exercised in its full glory. Despite headlining at the most popular music festival in the US – the two-weekend total of 250,000 tickets sold out soon after going on sale – Tame Impala had splashed so much cash on the production that it was essentially nullifying any profit from its two performances.

For Parker and his team, this was shrugged off as the cost of doing business. They knew Coachella’s bookers had taken a gamble by offering them this prime-time slot. Tame Impala’s third album, the Grammy-nominated Currents, reached No 4 on the US Billboard chart in 2015, and No 1 in Australia and the Netherlands – but in the US the act doesn’t quite have the household-name status of Grande or Gambino, or of previous top-billed performers such as Beyoncé, Eminem or Guns N’ Roses.

Accordingly, no expense had been spared in repaying the good faith shown by the American bookers. Given the layered complexities of Tame Impala’s music, the five performers tend to spend most time on stage concentrating on the hard work at hand rather than projecting their personalities – hence the heavy emphasis on the light show, complete with lasers (the rental bill for which was somewhere in the vicinity of half a million US dollars) and 18 confetti cannons.

Much of the world’s popular music industry, including kingpin bookers for other major events, keeps a close eye on Coachella. And so it was with metaphorically crossed fingers that Parker stepped onto the stage in the desert and shouldered his guitar, silently hoping that the show would act as a huge billboard for future bookings. “About halfway through, we realised we might not make any money, even though we’re getting paid more than we’ve ever been paid before for a festival,” he says. “So we didn’t make any money from Coachella; I don’t even know that we broke even.

“It was a $2.8 million job interview,” adds Parker with a laugh. “Hopefully, we’re hired.”

Outside is a busy street not far from Fremantle’s beachfront; inside is a soundproofed, airconditioned cocoon that’s also the first house Kevin Parker owned. Three years ago, he decided to knock down the internal walls to create one big open space. In front of a large computer monitor is a comfortable swivel chair where his skinny backside has logged thousands of hours agonising over every minute detail of his elaborate arrangements. A battery of keyboards and synthesisers is adjacent to a mixing desk and all manner of recording equipment; a small front room is occupied by a drum kit and not much else. All this was once somehow contained to a single bedroom, but as his audience has expanded, so too has Parker’s studio. A bed remains in one corner of the room, although it’s currently occupied by two acoustic guitars and a metre-long plush tiger toy.

It’s a week before Christmas and Parker has only just returned to Fremantle after spending six months in Los Angeles, where he and his wife last year bought a five-bedroom home in the Hollywood Hills. When not touring, this is the rough shape of their lives now, dividing their time between hemispheres.

Before leaving for Australia, he sat through an extensive inquisition by members of the European media ahead of the release next month of his fourth album, The Slow Rush. Some musicians disdain this aspect of the job but if Parker does, he hides it well. An engaged and engaging interviewee, he’s as close to an open book as you’re likely to find among rock stars, happy to answer any question while regularly rearranging his shoulder-length brown hair.

By any measure, the musician’s year was filled with significant highs, including marrying his high-school friend Sophie Lawrence at a West Australian vineyard in February. The funny thing about Coachella, though, is that he can’t recall much in the way of specifics. The same goes for headlining at the equally big-deal British festival Glastonbury, performing on US TV show Saturday Night Live, and closing the opening night of Australian winter festival Splendour in the Grass, held near Byron Bay in July. The foreground of his memory is filled with writing and recording the new album. “The reason I don’t remember it so well,” Parker says of Coachella, “is because even though it was stressful, it’s still a drop in the ocean compared to me finishing the album. In my head, it’s just been me in the studio the entire year.”

For someone whose life is spent more or less enveloped in sound, Parker is surprisingly fixated on smell. A third of the way through a sprawling three-hour conversation conducted while sipping pale ale and lounging on a couch that faces the arsenal of aural weaponry at his disposal, he draws on a peculiar analogy in an attempt to describe how he approaches songwriting. “It all boils down to a song having a core impulse,” he says. “Smelling a deodorant can from when you were 16 years old is a feeling; a nostalgia of being young, and possibly in love. There are no words attached to it; there’s nothing else other than that emotion that it gives you. There are many experiences that are felt the same way, and I feel like songs are really good at describing those.”

Later, when asked about one of the several bass guitars in a rack near a non-functional fireplace, he picks up the slight four-string instrument and lovingly works the fretboard. This vintage Hofner bass is the single most-used guitar in his collection, having appeared on each of the four Tame Impala albums. In 10 years he’s never changed the strings, nor played it live. Years ago, he stuffed Paris Metro train tickets inside its wooden body to cure a buzz that was bothering him. In November 2018, when his rented house in Malibu was about to be engulfed by a bushfire, he grabbed the Hofner and his laptop – which contained all his work to date on The Slow Rush – and left the rest to the flames. He lost about $30,000 in musical gear.

Still, Parker is pragmatic about the role of this particular instrument in his creative life to date. “It’s nothing other than what it is as wood and metal,” he says. “I’m sentimental, but I’m more sentimental about things that, in a way, don’t have a purpose.” After a pause, he returns to the topic of olfactory recall. “I’ve got a box full of old deodorant cans from throughout my life,” he says. “Every now and then, when I’m clearing shit out or moving house, it’s like a f..king time warp; it’s like a memory machinegun tour of my life.”

Why keep them? “Because I wouldn’t want not to be able to visit myself when I was different ages, you know?” he replies. “I could smell any of them and tell you exactly where I was and who I was; what I was doing; what I was feeling; who I had a crush on. For me, smells carry more nostalgic weight than anything else. Listening to a song you haven’t heard for years is like taking a trip down memory lane. But there’s no more immersive trip than a smell. It reminds me that we’re human.”

In 2011, while touring with Future Music Festival, Parker met English singer-songwriter Mark Ronson, who was on the bill with his band The Business International. At the time, Ronson was better known as a record producer working with the likes of Amy Winehouse and Adele; it was years before his global hit Uptown Funk, which featured vocals from R & B artist Bruno Mars. That was the lead single from Ronson’s 2015 album Uptown Special, on which Parker appeared as a guest on several tracks, including the unmistakably funky Daffodils. “He’s very much a mentor,” says Parker of Ronson. “He’s basically the person who showed me, unknowingly, how to be a people person in music, and how to connect with other people. He’s someone that’s so warm and humble and down to earth, but can communicate with anyone. So if I’m working with an artist – whether it’s being a producer or a songwriter – I basically pretend that I’m Mark Ronson.”

If the pair hadn’t met then, perhaps Parker wouldn’t have become the sought-after collaborator he is today; perhaps he’d still be stuck in his comfort zone inside the studio, toiling on his lonesome. Through Ronson, he worked with Lady Gaga on her 2016 album Joanne, including co-writing its lead single Perfect Illusion. And he has written and produced tracks with hip-hop artists such as Kanye West, A$AP Rocky and Travis Scott.

“Kevin is such an amazing talent, not only because he plays and produces and writes and sings everything; that wouldn’t mean anything if it wasn’t great,” says Ronson. “I think he’s my favourite person making music today. He’s pretty left-field, and instead of him coming to the centre, everybody has moved a little bit toward him. It’s cool to be weird and psychedelic, and you don’t maybe need as much commercial mainstream radio play to be important, or to register in the culture.”

Ronson recalls a recent experience of being in the studio with Parker and Abel Tesfaye, a Grammy Award-winning Canadian R & B artist who performs as The Weeknd. “Abel kept saying, ‘When you put out that record [Currents], you shifted the culture’. I feel like, with New Person and The Less I Know the Better, Kevin’s in a bedroom in f..king Perth, cut off from the entire world – but shifting culture.”

For most of his 34 years Parker has been captivated by the concepts of time and change. The fascination extends beyond making music: in the backyard behind the studio, an old acoustic guitar sits in a beached tinny that hasn’t seen water for many years. Parker is curious to see what exposure to the elements will do to the instrument. In his eyes, there’s beauty in the degradation of an object that no longer has a clear purpose.

Those themes have been on display in his songwriting: his 2010 debut InnerSpeaker contains a track named The Bold Arrow of Time, while Currents features Yes I’m Changing, Past Life and Eventually. The threads continue to unspool on The Slow Rush. The cover artwork is a digitally altered photograph taken by Neil Krug in Kolmanskop, Namibia. It’s a ghost town with houses in the process of being swallowed by the desert. The sand has a liquid quality that makes it unclear whether the incursion occurred overnight or over many years. As soon as Parker stumbled across pictures of the place, he knew he’d found the location for his album cover. The fact that he felt the need to go there in person, and that he now had the resources to make that 30-hour trip, shows how far he’s come since Lonerism, the 2012 album that drew international applause and a Grammy nomination thanks to hit singles Elephant – a lumbering rocker whose midsection is given over to a serpentine instrumental – and Feels Like We Only Go Backwards, a deeply melancholic and melodic song that was later used as the basis for a track by US hip-hop star Kendrick Lamar.

It was the 2015 album Currents that proved Parker’s ability to write music with wide appeal, and it has had remarkable staying power. Third single and break-up jam The Less I Know the Better has become his single most popular song, with platinum certification in the US, and R & B artist Rihanna paid the ultimate compliment by including a six-minute cover of New Person, Same Old Mistakes on her 2016 album Anti.

By the time The Slow Rush is released next month it will be nearly five years between albums – an eternity in the world of pop culture, where music has never been so accessible nor so disposable. Ahead of its release, Parker has published several singles. The first, Patience, begins with a question that could be interpreted as a wink to his many impatient fans: “Has it really been that long?” That song won’t appear on the album, but the two that followed – Borderline and It Might Be Time – will. And in December, Parker published a song that directly addresses a chapter of his life that closed while he was recording his first album when his father, Jerry Parker, died from skin cancer at 61.

Born in Sydney, Parker was about three when his family moved to Kalgoorlie for his father’s work as chief financial officer of a South African gold mining company. After his parents split, they moved to separate households in Perth. Kevin grew up with his mother, Rosalind, while his brother lived with Jerry – until his parents decided to leave their respective partners and get the whole family back together under the one roof in Subiaco, when Kevin was about 15. The honeymoon period didn’t last long: within a year, Jerry had reconciled with Kevin’s stepmother, and the two brothers were thoroughly confused by the emotional whirlwind they’d just endured.

Given this turmoil, Parker’s relationship with his father was fraught. Jerry was a passionate music fan who bought his son his first guitar and taught him how to play rhythmic chord progressions so that he could add Shadows-style lead riffs over the top. He’s also the one who, after finding a bong, beer bottles and stolen goods in his teenage son’s room, cut him off from his mates, thus dooming him to a largely solitary adolescence. The social isolation left Kevin plenty of time for bedroom tinkering with musical instruments and he built a strong connection with Dominic Simper, his long-time friend who played bass in early iterations of Tame Impala’s live line-up before switching to guitar and keyboards. Today, the live band is completed by synthesiser and guitar player Jay Watson, drummer Julien Barbagallo and bassist Cam Avery.

After high school, Parker began studying engineering at university, then switched to astronomy. He came close to graduating before defying his father’s warning and throwing himself into a music career. It helped that he was living in a share house filled with other musicians, and that he was already playing in several bands. Under the name Tame Impala – rooted in an oblique reference to an imagined meeting with a wild African animal – he uploaded a few songs to MySpace, where he was discovered by Glen Goetze, A & R manager of record label Modular, and offered a recording contract. The pair still work closely today, with Parker trusting Goetze’s ears more than just about any other pair on the planet besides his own.

Jerry saw the start of Kevin’s blossoming career, but didn’t live to see the significant impact his son has made on global popular culture. On The Slow Rush, the six-minute song Posthumous Forgiveness is split into two distinct sections. It’s the latter half that speaks to the second word in the title, as its final words are unmistakably the sound of a young man who misses his dad: Wanna tell you ’bout the time / Wanna tell you ‘bout my life / Wanna play you all my songs / And hear your voice sing along.

His wife Sophie was on a daily hike up a mountain in Los Angeles when she first heard the song in its final form. “The song resonated with me because my father’s gone as well,” she says. “I could not stop crying for days. It just hit me so hard every time, and I could hear almost the break in his voice when he was singing it. I’d never heard him put so much heart and his feeling into a song so vividly, or so literally.”

The sun has set, the brilliant light bouncing off a neighbour’s wall replaced by lengthening shadows. Before we walk up the road to his local pub, I decide to risk asking Parker if he’ll play me the first minute of the first track of his new album.

He has outlined an overarching theme that arose early in the writing process: he wanted to use the first and last tracks to tell the story of a character who chooses to spend just one more year acting out – irresponsibly, and to excess – before smartening up and resolving to get his life in order. As he imagined it, these two tracks would bookend the album, the opener setting the tone with a question that could be an internal monologue – Do you remember we were standing here a year ago? / Our minds were racing, time went slow… – and ending with a final track that captured the last hour of that year. Parker hastened to add that this idea didn’t amount to The Slow Rush being a concept album, but admitted an abiding fascination with works that sharpen their emotional point by working within such parameters.

Knowing Parker’s chronic inability to feel his songs are ever truly complete, I know my request is risky and could go either of two ways: he’ll be able to contentedly sit back and listen to the finished work, or the moment will trigger a spiral of frustration that will see him retract the album, tinker away and blow more deadlines.

Thankfully, it’s the former: Parker cheerfully says yes; he hasn’t heard the finished mix played in the room where he wrote so much of it. After plugging in his laptop and digging through his folders to find the right files, what emerges from the speakers at high volume is the eerie, juddering vocal sample that opens One More Year. Soon, a backbeat is foregrounded in the mix, followed by wispy synth chords, a compact bassline and Parker’s voice. Like the best of the several dozen songs he has written and released under the name Tame Impala in the past decade, it’s an evocative work that conjures feelings and memories from the near and distant past.

Earlier, when I asked him why he thought Currents made such a global impact, he demurred at first. Perhaps for good reason: getting too caught up in examining past successes and failures is the sort of thing that can send artists off chasing their own tail or, worse, hurtling into a pit of self-doubt and despair. Yet while reflecting on his booking agents’ surprise at growing demand for tickets to Tame Impala gigs despite the lack of new music, Parker landed on a summary of his art that felt resonantly true. “I think it’s the kind of music that slowly gets under your skin – maybe because of the melodies, and the chords, and the rhythms,” he said. “It’s the kind of music that you slowly fall in love with.”

After letting that immense opening track play well beyond the single minute requested, Parker laughs when he realises the version he’s been playing wasn’t even the final mix. Only he would notice; I didn’t, despite playing the album on repeat in the week before our meeting. Now, to my surprise, he begins clicking through several other tracks and continually bumping up the volume. Soon, these songs will belong to millions of people around the world. Perhaps some of them will shift culture once again, just like the last collection he released. But in this moment, they are his alone.

As he sits in the swivel chair where he has logged thousands of hours, one of modern music’s greatest young minds listens to the work that has consumed him for more than a year. Judging by the way he nods to the beat, it seems he likes what he hears.

The Slow Rush is released on February 14 via Universal. Tame Impala’s national tour begins in Brisbane (April 18) and ends in Perth (April 28).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout