Kasey Chambers on musical highs, personal lows – and finding a ‘perfect love’

The darling of Australian country music has always worn her heart on her sleeve. But finding love – with a bandmate 19 years her junior – is helping her hit the highest notes of her musical career.

It’s a Tuesday when I arrive, which means Kasey Chambers has been spending her day caring for a cute blond boy – an arrestingly trusting child who soon raises his palms to me with a wordless request to be picked up and carried.

“Have you got a new friend?” she coos at the cheerful sprite, who’s soon to turn two. “Or were you just sick of me, and there’s a new face?” Jude isn’t related by blood, but that wide-armed gesture mirrors Chambers’ disarming openness.

In fact, the boy is the son of her ex-husband, fellow country musician Shane Nicholson and his partner Emma, who live nearby. Each Tuesday, Chambers joyfully slips into Mum mode for Jude, whose colourful trucks are scattered on the kitchen floor of the stylish home.

As down-to-earth as Chambers is, I hadn’t expected to find one of Australia’s biggest music stars entangled in this arrangement. At 48, her three children are well past this stage. But a thicket of relationships grows here and it’s worth briefly unpicking, not least because I discover that she’s happily ensconced in one.

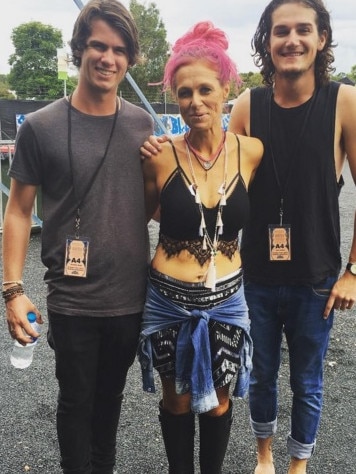

Her youngest two children with Nicholson – son Arlo (17) and daughter Poet (12), Jude’s half-brother and half-sister – live here, an idyllic bush property on the NSW Central Coast. Her eldest son, Talon, is now 22 and has moved to Perth, but his dad Cori Hopper visits the Central Coast home regularly for fiercely contested table tennis games with his best mate Brandon Dodd, Kasey’s boyfriend, who is 19 years her junior.

That all may sound like a tinderbox, but I find this complex modern family getting on with their lives in surprising harmony. The Chambers clan is imbued with warmth, loyalty and open-hearted generosity that is a joy to witness.

As I first walked up the driveway to the property, which abuts a national park near a small seaside town, I’d heard the muffled thump of a bass drum and the chiming of clean-tone electric guitars emanating from the Rabbit Hole, a custom-built recording studio behind the house. Chambers and Dodd, 29, moved out here during Covid, and built up the place – for a “musical retreat” – complete with a wooden stage that’s used for occasional gigs played to friends and neighbours. Chambers styled the interiors, she says, indulging an “obsession” for wabi-sabi decor.

Most days, musicians work within earshot of the house, with Dodd – the guitarist in Chambers’ band for the past nine years – often the producer and engineer on recording sessions. This hum of background noise is the right soundtrack for Chambers, for whom singing and playing music is like breathing. Her own songs have been speaking to country music fans since she toured with her travelling family band as a 14-year-old, and to a far bigger audience since she broke through with her award-winning debut album The Captain in 1999.

But this also represents a new score. A restless, changeable soul putting down real roots. At her bushland home Chambers does most of the cooking; long and slow meals or wood-fired pizza baked in the oven outside. On her phone lock screen, a picture of Dodd and her children.

As a sunny late August afternoon descends into cool dusk, the family headquarters pulses with energy and endeavour watched by a muscled Staffy named Buddy. Family members spanning generations, ex-partners and musicians come and go with breezy informality. The engine of the operation takes the form of a 159cm-tall brunette wearing brown boots and a light-coloured dress, who gives a tour of the property while I carry Jude.

This is where Chambers has written her 13th album, Backbone, stepping up as a producer for the first time in her 25-year solo career; she recorded it at Rabbit Hole, with Dodd manning the six-string and co-writing a few tracks.

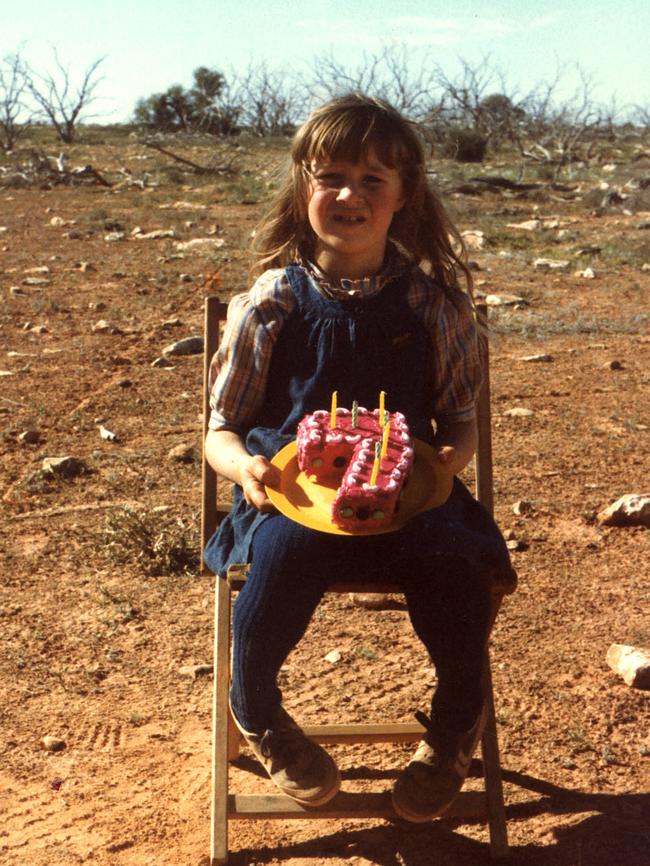

Anyone who has been to a Chambers gig has witnessed a compulsive storyteller. There’s the one about growing up, a homeschooled nomad on the Nullarbor Plain, as her dad Bill earned a living from hunting foxes and rabbits for their skins; the one about Worm, her beloved best friend and roadie, giving her the defining lyric of Barricades & Brickwalls; how she met a teenage Dodd and his former bandmate, Josh Dufficy, playing under the name Grizzlee Train at a beer garden gig at a Central Coast pub in front of a handful of people – “they played to us and to some drunk lady dancing in the corner, but they had so much heart and soul,” is how she would tell it to The Australian’s late, great music writer Iain Shedden seven years ago.

“They did something to me. I see great musicians all the time, but they had a great innocence to them. I chatted to them afterwards. It felt like I’d known them my whole life. Within a couple of days we were just jamming all the time. It wasn’t long after that I asked them to join the band.”

As we hoof around the house she explains, “I love telling stories … I want people to go home feeling like they know me and my family, and my stories of where each song came from, and my good parts, my bad parts, my emotional parts, my funny parts. Everything.

“I remember a drummer ages ago saying to me, ‘Don’t you get sick of telling the story about what that song was about? You tell it every night’. And I’m like, ‘Do you get sick of playing the song every night?’ And he said, ‘Nah, I don’t – I love playing the song every night. I get lost in it.’ I said, ‘That’s what telling the story is like for me.’”

Backbone’s title is a pretty simple metaphor: music is her backbone, “harder than stone”, and its 15 tracks are drawn from her own life. There’s songs about Arlo, Poet, Bruce Springsteen, divorcing Nicholson and falling in love with Dodd; and an unexpectedly spectacular reworking of an Eminem hit.

“It’s certainly the most production I’ve ever done on a record,” she says. “I had a pretty clear vision beforehand of what I wanted each song to sound like, and they all turned out like that – but better, because then the musos got to put their little flavour on everything. I love it when everyone brings their thing.”

Backbone is a great album. But what has truly energised this assignment is its sister project: a gripping book, in the mongrel memoir style of Paul Kelly’s How to Make Gravy, with the unforgettable title Just Don’t Be a Dickhead, And Other Profound Things I’ve Learnt. It was composed in the Notes app of her iPhone across five or so months late last year.

She writes modestly in its introduction: “I know I don’t share my stories like professional writers with brilliant, well-informed, intelligent words and sentences carefully crafted to sound artistic and poetic. I mean, f..k. I ain’t no Shakespeare.” Yet her prose leaps off the page, and some of the areas she ventures into with her flashlight honesty reveal genuine insights into the life of an extraordinary Australian.

Littered throughout Just Don’t Be a Dickhead are funny quips and turns of phrase – the main motif is her “foghorn” (her inner voice) – and even a recipe for hot lentil soup. Short, sharply written lessons, bolded and underlined, include:

Meditation might actually be better for my mental health than watching gruesome true-crime documentaries on Netflix.

There’s nothing like an invasive vaginal swipe to bring you back down to earth. (This was the time when the family doctor sent a note that simultaneously congratulated her on receiving an ARIA Award and reminded her that her pap smear was overdue).

Being proud of myself and my achievements does not make me a dickhead.

Being strong doesn’t make you a bitch. And being a bitch doesn’t make you strong.

Chambers isn’t too concerned about how people will respond to Backbone: she knows by now that some people will pause their lives in a rush to connect with her newest music, while others jog on. But she is uncharacteristically anxious about the book’s reception. “My goal is not selling the absolute most copies that I possibly can; if that were the case, I would have written it really differently,” she tells me. “I would have gotten someone else to help me write it. I would have tried to make it more commercial. I would have probably gotten rid of all the swearing in it – and my mum would have been a lot happier with that, too.”

Less than an hour later, when her mum Diane walks in the back door for a brief stopover en route to a pottery class, she’s instructed with a grin: “You’re being recorded, Mum, so don’t say anything true about me.”

Like her daughter, Diane greets me with a hug, but she can’t mask her disappointment at having just missed a cuddle with Jude, who’s been picked up by his mother. “On Tuesdays, everyone calls in just to see the cute kid,” says Kasey with a cackle.

We head back inside, where mushrooms and capsicums cook on the stove top. They’ll go on doughy bases laid out on the bench to feed the studio musicians after they finish the session.

It’s all a far cry from the peripatetic life Chambers once knew. In 1986 her parents, who’d fed her and her older brother Nash on a diet of American folk and country music and local country artists like Slim Dusty and Tex Morton, decided to pursue their own music career. The family toured throughout the 1990s as the Dead Ringer Band, a proper travelling musical circus with Kasey as lead singer from the age of 14. They amassed ARIAs and Golden Guitars before Bill and Diane’s divorce busted up the band in 1998.

When Chambers established herself as a solo artist the following year with The Captain, she was a perplexing mix of wide-eyed innocent and seasoned professional. She had played Nashville and hung out with rock stars but was overwhelmed to discover the hypersexualised reality of ’90s stardom. An eating disorder would follow.

In her new book she describes benchmarking herself against artists such as Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Shakira and the Spice Girls, writing: “On one hand, I didn’t even really want to be anything like these artists – musically or image-wise – but I was also a young girl, and these were the main female role models that young girls were hearing on the radio and seeing on the covers of magazines and TV screens. Sometimes, I would hear their songs and see their perfect, sexy bodies dancing around in their music videos, or their beautiful, flawless faces on the magazine covers, and I just felt so … different. I felt so real. But not ‘real’ in a good way…”

Wracked with self-doubt, she writes, she released the astonishingly vulnerable song Not Pretty Enough in 2001. It went to number one on the mainstream singles chart, became a three-time platinum-selling single and took the album Barricades & Brickwalls to seven times platinum. Seven ARIA awards came off the back of it all, with gongs for Best Country Album, Best Female Artist and Album of the Year. “The thing I once saw as my biggest weakness became my greatest strength,” she writes. “My life was never the same again.” And then there’s another lesson underlined: Be brave enough to be vulnerable.

The most surprising track on Chambers’ new album is the bluntly titled The Divorce Song, wherein Chambers and ex-husband Shane Nicholson openly riff about their failed relationship and its aftermath. In its opening lines are a series of cutting lines sung in harmony:

We said ‘til death do us part’

But death didn’t come quick enough

Maybe we did it all wrong

Kinda f..ked everything up

The promises turned into prisons

On either side of the divide

It was til death do us part

‘Til we knew our hearts had already died…

For a while there, Nicholson and Chambers were the king and queen of Australian country music, the successors to the songwriting and performance team of Slim Dusty and his wife Joy McKean. Married in a barefoot, backyard wedding at Avoca Beach in 2005, they toured together and collaborated on ARIA Award-winning albums; the last, Wreck & Ruin, came just before a painful split in 2013.

It’s the Wednesday morning after my pizza evening at the Chambers place and I’m back at the homestead. While her partner, Dodd, makes us coffees topped with some barista-level latte art, Chambers cheerfully recalls writing The Divorce Song with her ex-husband. “We wrote the song together … over text message,” she laughs. “I was like, ‘I’ve got this idea for a song – can you see anything in it?’ He’s like, ‘Oh yeah, maybe, let me mess around with it’. He’d send something back, and we went back and forth – and then the next thing, it’s the newest song on the album. I think it’s a really special moment on the record.”

The Divorce Song has one of the album’s strongest melodies in its chorus, as Chambers and Nicholson sing to each other:

We couldn’t survive as the marrying kind

But we do divorce pretty good.

Chambers had a grounding in divorce, but also in reconciliation. “My mum and dad were like that too,” she says. Today Bill plays guitar in her band, while Diane handles the merchandise desk at her concerts. “Obviously they went through a hard time, and they broke up,” she says. “So did Shane and I, and so did Cori and I. We’ve all been through that hard bit, and you’ve got to go through that, too. I know you can’t just wake up the next day and go, ‘Alright, everyone just be friends now’. You’ve got to get through that hard shit.

“After a while, it is a choice to put your own shit aside and just go, ‘This doesn’t have to be about this’ – and then you start to see all the good things about the person who was a part of your life as well.”

As we carry our coffees out to the recording studio, she says: “It’s not perfect all the time. I’m not saying that we don’t still have our moments, but overall there’s an element of respect there from both sides.”

There is, she points out, another lesson underscored in the book: Lead with an open heart.

Which brings us to Dodd, or “Brando” as she affectionately calls him throughout her book. Now 29, he has been working in and around the Chambers family business for a decade, writing, playing and touring on every album since 2017’s Dragonfly. But it’s only in the pages of Just Don’t Be a Dickhead that she publicly refers to him as her partner for the first time.

I ask the story of how they became more than just bandmates. “We started touring and we eventually ended up getting feelings for each other,” she says. “I think playing music together helped us to fall in love, because we ... really connected on a musical level, and that probably helped our connection to go deeper.”

Their relationship, which she describes as a “match made in heaven”, was so gradual that they don’t have a firm anniversary date. Six or seven years ago is her best guess as to when the romance began.

“Connecting with someone creatively is a really beautiful thing ... and I’m really glad that came first. You can probably even tell when we play together that that really does still feel like the grounding to our relationship,” she says. “We still love sitting around playing together. Sitting around a campfire, he’ll get the guitar out, I’ll be cooking, and we’ll sing together. That’s a perfect love for me.”

With a laugh she adds: “It doesn’t really get any better than that – and then he gets fed at the end. He makes the coffee, I make the dinner, then we play music together. I mean, I can’t really think of much more that I need.

“We both really want to support each other in becoming the best people that we can, and having a fun life, you know?”

The 19-year age gap doesn’t bother her, she says. She writes in the book: “Despite our age gap leaning the other way, Brando was generally way more mature than me most of the time. Much more traditional than me. He had even decided not to own a smartphone anymore, and went back to an old flip-top phone so he wasn’t living his life through a screen.”

Dodd is a quiet presence for much of the time I spend with Chambers; he’s not the type, it seems, to submit to a formal interview, but before his client shows up for a recording session at Rabbit Hole that morning the couple allow me to watch them working through a few of their new songs. Propped up on stools, I film them performing beneath a naked overhead bulb. Behind them, guitars, banjoes and mandolins hang on the wall.

It’s an unfussy and unrehearsed jam, playing three songs from Backbone for the first time since they were recorded in this room. The duo are a little rusty and forgetful, gently flirty and almost a bit nervous in front of a stranger – but mostly, in melodious harmony. One song ends when Chambers forgets the second verse and apologises, and Dodd replies, “It’s alright – we’ve got a better one in us, anyway.”

There’s a tricky chord progression and she stops him and asks if he’s playing it right (he is) and then she laughs. She knows she’s testing him at the hardest part of the song. When they nail a take of A Love Like Springsteen, a co-write with lyrics dotted with famous song titles from New Jersey’s godfather of heartland rock, they celebrate with a gleeful whoop and a fist bump.

That’s not to say the relationship has all been plain sailing. In her book Chambers writes: “Just before the pandemic hit, I had already gone into some kind of lockdown … Brando and I were having some relationship problems – we’d ended up in couples’ therapy, which then turned into singles’ therapy for a while so we could figure out who we were separately before we chose who we wanted to be together.”

Yet they made it work, “slowly getting through some relationship stuff that took time, work and energy”, before moving to their rural paradise. “Both of us knowing how healing nature can be, we decided to move to a bushland property out of town. A fresh start, a natural environment, country life and some space…”

Chambers has worked hard to banish her insecurities. She writes of the makeup artist who said to her, “You could definitely do with some Botox, love” as she prepared to walk the red carpet for the Golden Guitar Awards in Tamworth – advice she rejected. “I have almost 50 years’ worth of wrinkles on my face from all the laughter in my life. I have a bunch of grey hairs on my head, popping through from all my life experiences. My boobs hang down to my knees when I don’t wear a bra from feeding my three babies.” That life lesson, she writes, is this: Am I not pretty enough? Who gives a f*ck.

Chambers’ book is strewn with famous names. She reproduces the beautiful poem Paul Kelly wrote for her when she was inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame in 2018, at age 42. And Keith Urban writes in the foreword to the book: “I met Bill, Diane, Nash and ‘little’ Kasey sometime in the late ’80s. I loved them immediately – because they were REAL PEOPLE. You knew it right away. Kasey, man, even as a young teenager, was already full of fire, charisma and mystic earthiness. Over the years I’ve watched her blossom into this extraordinary artist, singer, songwriter, storyteller, Aussie icon…”

But for the purposes of this article, I’ve asked a handful of her fellow artists to share their responses to a simple question: “What does Kasey Chambers mean to you?”

The answers are glowing and heart-rending and intimate. I take a risk and read them to her aloud. Text messages from singer-songwriters Troy Cassar-Daley and Sarah Blasko, quotes transcribed from Ian Moss and John Williamson, a video message from Missy Higgins. And this slyly subversive missive from her ex-husband: “She is a bald-faced liar! In our marriage vows, Kasey pledged to cook me lamb shanks anytime I wanted them, but since our divorce she hasn’t once kept this promise ... But she’s the mother of my first two children, and also now regularly babysits my third, so I’m letting it slide.”

The most powerful messages come last. A note from country singer-songwriter Felicity Urquhart, an acclaimed performer, who had tried to film a video message but couldn’t get the words out. She describes the suicide of her husband Glen “Goonga” Hannah in 2019: “The darkest hour of my life was five years ago when we lost Glen. I remember feeling like I couldn’t breathe ... I’ll never forget looking through my tear-flooded eyes and seeing you walk down my driveway – your own eyes flooded with tears. You held me in my grief and reassured me that there were friends here to help. That moment is forever burned into my memory.”

Chambers writes movingly about this in her book. “That was a pretty hard chapter to write, that story in there,” she says, wiping her eyes. “Then I decided that I would talk to Fliss [Felicity] about it, and see how she felt about it, and if I could send her the chapter. She was so sweet; she just sent it back saying, ‘It’s absolutely perfect’.”

The last note is from Jimmy Barnes, penned not long after leaving hospital following hip surgery. He recalls recording and performing with Chambers – “just the two of us around a microphone singing into the darkness ... I think if Kasey wasn’t touring she would be telling stories to anyone close enough to listen to her. Music is her only path. Music is her life. And I am so glad that she shares that path, that life, with us all.”

After more tears, she gets up and gives me yet another hug.

Rewind to January this year. I’m sitting a few rows from the stage in Tamworth Town Hall, watching Chambers soundcheck with her band a few hours before the doors open. As a headline performer at the Tamworth Country Music Festival, Chambers, wearing a flowing white dress and black-rimmed glasses, is obviously the boss among her bandmates – dad Bill and boyfriend Dodd on guitars, drummer Syd Green and bassist Jeff McCormack. Everything starts and stops at her command.

When, in a split second, she switches from talking into the microphone about her guitar sound to singing at the top of her voice, it’s as though a spell is cast in the empty room. An absolute weapon of an instrument lives inside Chambers, and when awakened it has an all-encompassing power. Afterwards, a woman sitting in the stalls claps and cheers. “Aww, thanks,” Chambers beams.

Backstage afterwards, I say a quick hello and thank her for letting me sit in. We make loose plans to catch up later in the year, foreshadowing what would become this cover story in The Weekend Australian Magazine. “We might even have some interesting things to talk about,” she adds, smiling. “See you a bit later. The best song’s last, so you kind of have to stick around...”

A few hours later I watch her perform an impressive 100-minute set to a thousand or more fans, in which she taps into deep emotions amid a whirlwind of freakish vocal notes, before undercutting the whole effect with an offhand joke or some toilet humour.

In an electrifying moment, three young women from the Academy of Country Music join her to harmonise and play fiddle on Not Pretty Enough. There’s a tearful moment afterwards before Chambers can compose herself and tell the crowd that she’s never felt less lonely when performing her signature song.

And then remarkably, the set has one last transcendent chapter. Its finale, a surprising cover of Lose Yourself by the Detroit rapper Eminem, aka Marshall Mathers III. An incongruous musical marriage. Chambers’ take on the rap begins with her standing alone at the microphone with her banjo, gently singing:

His palms are sweaty, knees weak, arms are heavy

There’s vomit on his sweater already, mum’s spaghetti

And he’s nervous, but on the surface, he looks calm and ready

To drop bombs, but he keeps on forgetting

What he wrote down…

Starting as a solo bluegrass piece, it grows into a full-band arrangement that stretches toward eight minutes and a storming, hard-rock coda, with Chambers finding passionate melody inside the lyrically dense, rhythmical piece of hip-hop.

She recasts the semi-autobiographical story of Mathers’ life as an emerging star (which he portrayed in the film 8 Mile) into her own manifesto; we see glimmers of a wild and sometimes frenetic childhood as a member of a country music-worshipping family, and then a peripatetic adult existence, but one with music always as its backbone. A fearsome wave of emotion passes from the stage and out across the audience.

After that, there’s nowhere else for the show to go. Chambers has lost herself inside this stupendous song, with her dad Bill’s lap steel guitar lines scything through its towering conclusion. A live version of Lose Yourself is the final track on Backbone. She was right: the best song was last.

Just Don’t Be a Dickhead is published on October 1 via Hardie Grant Books. Backbone is released on October 4 via Essence Music.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout