As the Fender Stratocaster turns 70, have we reached peak electric guitar?

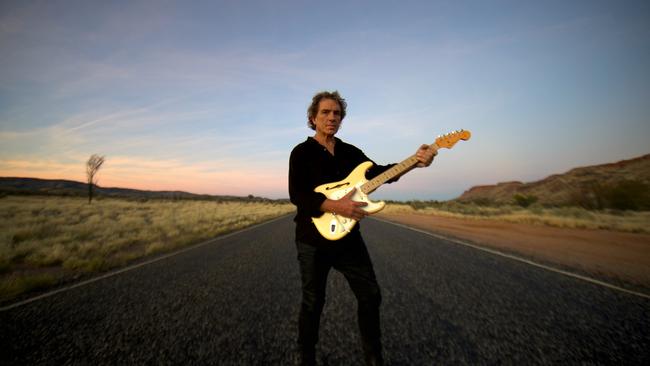

As the Fender Stratocaster — the world’s most recognisable six-string axe — enters its eighth decade, rock ‘n’ roll music is far from ascendant. Where to now for this totemic instrument of cultural change?

For most of the past 70 years, popular music has centred on the electric guitar, the portable instrument that emerged from obscurity among jazz and blues players to eventually take on totemic significance in the eyes and ears of music fans worldwide.

Rock ’n’ roll was born in the mid-1950s and its subsequent surge wouldn’t have happened without the sight and sound of players working their fretboards and setting alight a new movement.

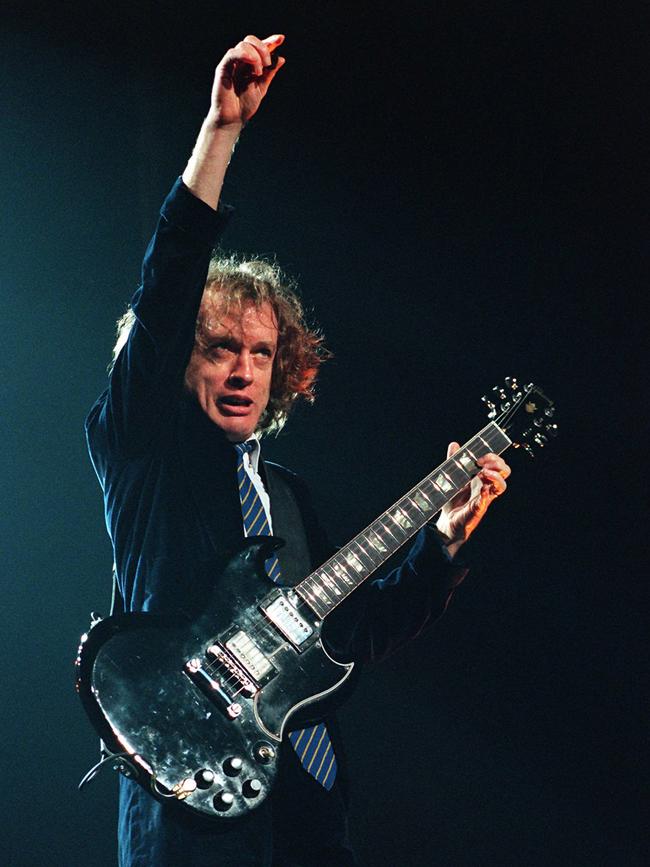

In turn, rock music became enmeshed with youth culture, as teenagers and young adults sought to break with their parents’ stodgy tunes by plugging into the sounds of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, AC/DC and countless other groups, for whom the electric guitar was an object of reverence and a key to unlocking a life less ordinary – and for their listeners in turn.

For decades, guitar-based music ruled popular consciousness and dominated the charts and the box office.

In music videos, on album covers and on performance stages, clocking images of sleek, phallic instruments played by rock gods and made by manufacturers such as Fender, Gibson, Ibanez and Yamaha became de rigueur.

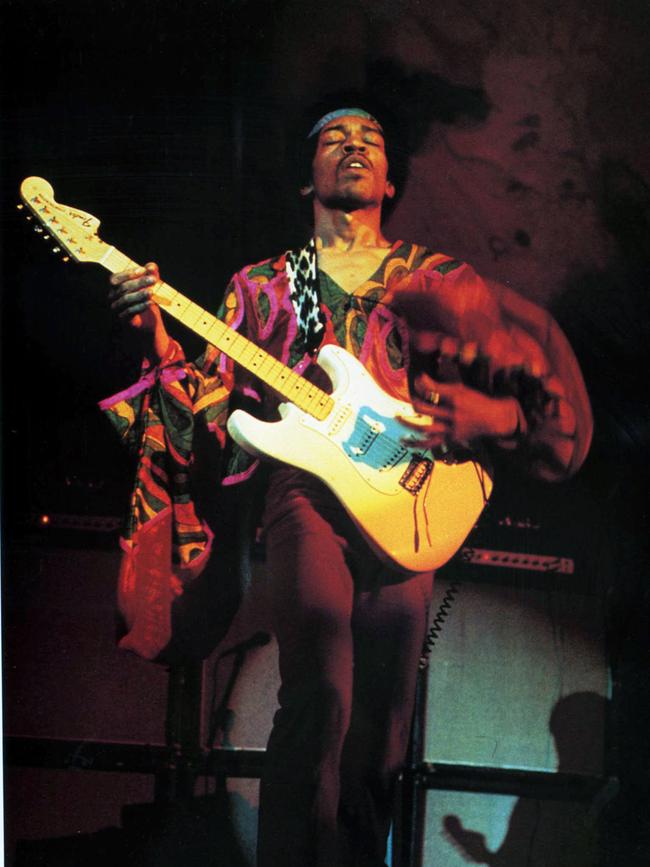

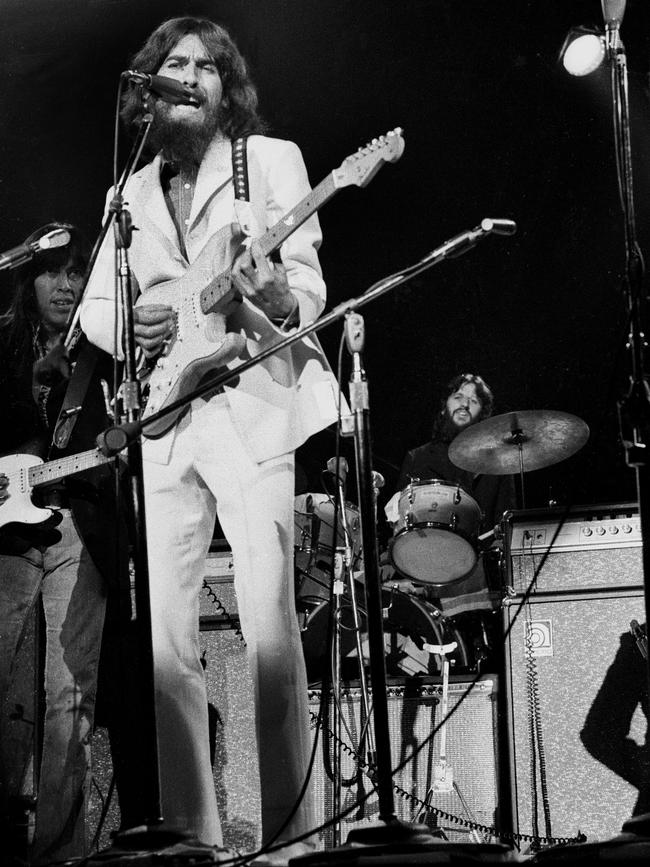

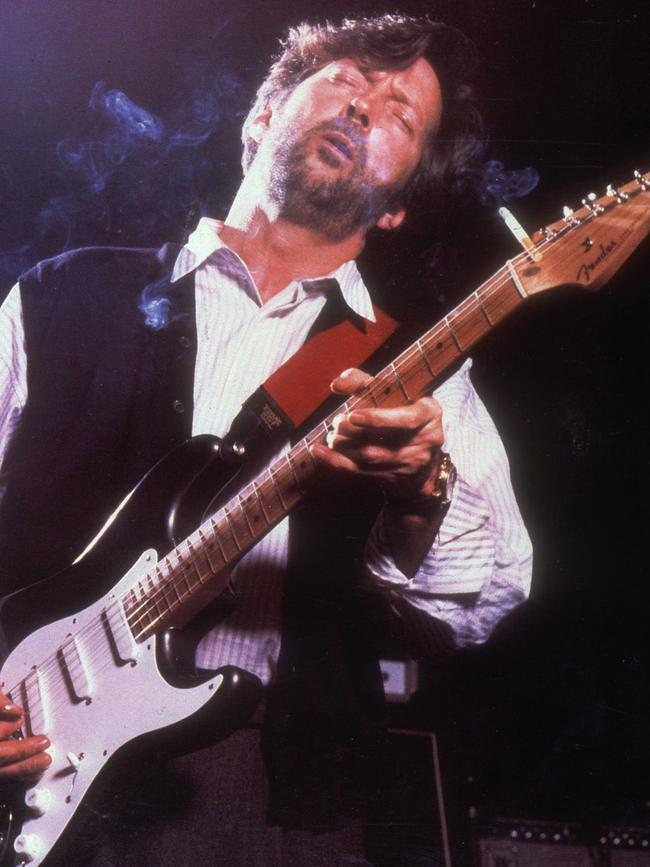

In the religion of popular music, the electric guitar was a holy object. Instead of the father, the son and the holy spirit, a billions-strong flock found salvation in bowing down at the altar of Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix and Angus Young. But as another generation-shaping guitarist George Harrison wrote, all things must pass.

Anyone glancing at the data supplied by the weekly popularity contest of sales charts can’t help but have noted a decade-long dearth of rock ’n’ roll music. What’s ascendant in English-speaking culture is pop and hip-hop music arranged with electronic beats and synthesised instruments. If electric guitars are present, they’re often used as supplementary tones rather than a defining voice.

Today’s stadium-filling singer-songwriters such as Taylor Swift, Ed Sheeran and Luke Combs each write and perform with acoustic guitars rather than electric instruments. Country music is booming thanks to rising stars such as Combs, but it’s a similar story therein, where strummed chords generally provide the musical bed among the genre’s biggest-selling acts, with flashy lead lines functioning as the occasional cherry on top, not the whole sundae.

All of which has posed a conundrum to electric guitar manufacturers: how do you capture and inspire the players of tomorrow when much of what passes for popular music now tends to treat their primary product as a background instrument at best?

Or more to the point: how do you sell enough of the bloody things these days to keep the lights on?

It’s a thought that likely has executives and luthiers waking in a cold sweat: what if we’ve long since reached peak guitar?

For some players – including this writer – one guitar has been enough for 20 years. Rather than enticing existing players to introduce more axes into their homes, though, the goal of guitar manufacturers over the decades has been to expand the pool of customers.

This task was inarguably easier in the past, when evolving subgenres of chart-topping rock music had listeners so inspired to emulate their heroes, from Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton in the 1960s, through to Slash wailing on his Gibson Les Paul out front of Guns N’ Roses in the 1980s, and on to the concussive, innovative riffs eked out by the likes of Tom Morello in rap-rock act Rage Against the Machine in the 1990s.

When they were omnipresent, electric guitars tended to have the look and feel of a renewable resource; a commonplace commodity in constant demand.

No longer. Sales data is closely guarded across the industry, but one marker appeared in a Washington Post article mourning “the slow, secret death of the six-string electric”. In 2017, writer Geoff Edgers reported that, across the previous decade, electric guitar sales in the US had dropped from 1.5 million annually to just over one million axes a year.

It’s not that we lack guitar heroes; Swift and Sheeran each fit that bill in their own ways, having both prompted countless players to learn major and minor chords on acoustic instruments since issuing their debut albums in 2006 and 2011, respectively.

Just as electric guitars require amplification to be heard, though, there’s a lack of visibility when it comes to popular players inspiring the next generation. This is a problem because, in the mass market, you can’t be what you can’t see.

Visibility isn’t an issue when it comes to the Fender Music Instruments Corporation in Tokyo. Its retail presence isn’t tucked away down a little-known alleyway whose entrance is earned only through inside knowledge whispered among existing musicians, as is sometimes the case for music instrument stores.

Instead, it’s designed to be discovered by high volumes of foot traffic shuffling between shopping destinations. It helps that the building demands your attention, thanks to the huge digital screen affixed to the face of three glass-fronted storeys. That giant, vertical screen plays an eye-catching carousel of musicians, all of them caressing and showcasing instruments that made this one of the world’s best-known music brands for 70 years and counting.

Dubbed Fender Flagship Tokyo and situated prominently in a fashion shopping district – beside a Samsung phone store and across the road from an Ugg Boots retailer – it represents nothing less than a mighty oar in the water for the US-based company, whose only official storefront anywhere in the world opened in the Japanese capital in June 2023.

A decade in the planning, the store is a ballsy attempt at keeping guitars alive in the culture while also hoping to reinvigorate sales, and according to Fender Asia Pacific president Edward “Bud” Cole, it has been working, with more than 400,000 people browsing its wares in the past 18 months.

“It’s not by chance we’re on one of the busiest thoroughfares, the Omotesando-Harajuku corridor, here in Tokyo,” he says while giving us a personalised tour.

“Hundreds of thousands of people walk by our store every day. We really thought it was important to be on the high street because we really wanted to elevate music and guitar-playing to be as important as all the other things that people are interested in.”

When Review meets Cole in mid-November, it’s on the eve of a product launch – a new line of guitars in partnership with Hello Kitty, the multibillion-dollar anthropomorphised white cat character created by Sanrio in 1974.

More significantly, it’s within the calendar year marking the 70th anniversary of what’s likely the most recognisable electric guitar shape and model in the world: the Stratocaster, designed by company founder Clarence Leonidas “Leo” Fender in California, and first brought to market in 1954 at an initial cost of $US249.50.

As author Dave Hunter noted in his 2021 book Fender: 75 Years, the company was on an enviable hot streak when it subsequently issued the Telecaster, Precision Bass and Stratocaster in short order. “We have to score a trio of successes in that brief 1950-1954 period that must rival any three consecutive product debuts by any company in any other industry,” Hunter wrote.

The Telecaster came first, and endures today, but it’s the Stratocaster that captured musicians’ imagination thanks to eye-catching appearances on camera by the likes of Buddy Holly (1957), Bob Dylan “going electric” in 1965 and Hendrix’s Strat-burning turn (1967).

Its space-age, double-cutaway look manages to feel futuristic both yesterday and today. Importantly, though not a guitarist himself – he preferred playing saxophone – Leo Fender listened to artists’ feedback regarding the solid-body shape of the Telecaster: with the Stratocaster, he opted to saw away contours where the instrument rests against the midsection and forearm, resulting in a much more comfortable playing experience.

A little history: after ballooning to more than 500 American employees amid the burgeoning rock ’n’ roll boom, Leo Fender – who never had great interest in running a business, despite owning a very profitable one – sold his namesake company to CBS in 1965 for $US13m, which was about the same price that CBS had paid to buy the New York Yankees baseball team one year before.

By 1979 it was selling 40,000 guitars a year, resulting in a reported $US60m income for 1980 alongside its line-up of amplifiers and other instrument sales.

Yet after a series of annual losses during a decade of flux in the guitar industry, CBS exited the business, selling the company to Fender’s executive team in 1985 for $US12.5m – less than its purchase price 20 years earlier.

While the new owners built a new factory in Corona, California, most Fender guitars sold in 1985 were made in Japan.

Today, the company continues to manufacture guitars in the US and Mexico, and works with additional factories in Japan, Indonesia and China. Since the internal sale in 1985, it has remained a privately held company that doesn’t report financial data, although it offers glimpses in press grabs.

In 2015, for instance, Fender’s revenue was about $US400m, with electric guitar sales accounting for 62 per cent of the total; in 2018 it sold more than one million guitars across its brands, including Jackson and Gretsch.

The company’s protection of its status atop the global guitar industry has overstepped the mark: in early 2020, the British competition watchdog fined Fender £4.5m for price fixing between 2013 and 2018. In a practice called resale price maintenance, it set minimum prices for its guitars and told resellers to sell at, or above, this price, and threatened sanctions against those who advertised or sold at lower prices. (Fender admitted to breaking the law and co-operated with the investigation, and the fine was reduced to reflect this.)

Single-digital sales growth was the norm for the sector until the Covid pandemic, when global lockdowns and millions of suddenly idle hands boosted demand for Fender products, growing about 30 per cent a year to $US1bn, that the company struggled to fulfil because of supply chain issues.

In Tokyo, Cole, 57, is a smooth-talking, pony-tail-wearing American whose background includes playing in a rock band – Arizona group Rain Convention, which supported the likes of R.E.M. and Radiohead – and working as an executive in high-end retail, most recently at Ralph Lauren, before he was recruited to lead Fender Asia Pacific in 2014.

He lives locally with his wife and their three-year-old daughter and, crucially, he speaks fluent Japanese, stemming from a sliding-doors moment when his manager threw him into auditions to sing lead vocals for Australian rock band INXS following Michael Hutchence’s 1997 death.

After meeting the group and impressing them enough to progress towards the pointy end of the selection process for what would become the reality TV series Rock Star: INXS, Cole elected to pull out in favour of devoting two years to learning Japanese to further his business career. (The band gig was eventually won by Canadian singer JD Fortune, who went on to front INXS from 2005 to 2011; Cole remains a firm fan of the group.)

As we pace through the store, whose open spaces are busy with shoppers of all ages late on a Monday afternoon, Cole is unafraid to stretch beyond the corporeal and get cosmic while chatting about all things six-string.

“There’s something very intimate, for me personally, about picking up a guitar, strumming a couple chords, and connecting to this universal thing called music,” he says.

“It really is galactic. I mean it: you take an electric guitar and you strum a minor chord. Go anywhere in the world – any remote island or culture – and every person will say the same thing: ‘That sounds kind of sad. It tugs at my heart.’

“For me, the guitar has been a best friend. Sometimes it’s been frustrating, but it’s always been there with me since I was 14 years old. I’m not a great guitar player by any stretch; I’m a strummer.”

After learning about our own background with learning the instrument, from our mid-teens onward, he then asks Review a small but potent question: how do we feel when we play electric guitar?

Optimistic, is the response. It’s a creative act, given that it’s creating sound from silence, but optimism is the top note heard.

Perhaps that’s connected to how hard it is to learn to play. Nobody sounds good when they first pick up a guitar, but through persistence, pushing past the pain and gaining command over what your hands are meant to do, a vista of possibility begins to open up.

“Well, you understand,” Cole replies, nodding. “I think it’s also just a symbol of life, in that anything worthwhile doing in life is going to be challenging to get to any level of competence, capability and skill, especially if you want to try to master that thing.

“But if you can get comfortable looking in the mirror at yourself and saying, ‘I’m OK with not being good at something until I’m good at it,’ the guitar was a great example.”

That optimism Review mentioned earlier? It’s deeply tied to that act of picking up your first guitar, whether it’s a thoughtful gift from a family member or bought with your own hard-earned money.

You know that you can’t play it yet, but you’re hoping that you can in future, while also knowing that only through effort and loyalty to repetition will you emerge on the other side with competence, and maybe a few great riffs now under your fingers.

“Totally,” replies Cole with a boyish grin. “And the neat thing about guitars is, even if you can’t play them, when you strap one on, you’ll look cool.You just throw the strap over your shoulder, and the testimonial is there.”

“You can look at Pete Townshend or Johnny Marr or Hendrix, and you can say, ‘I can already see myself in that.’

“That testimonial helps you stick with it – and then you get to listen to the music of your favourite players of today, and yesterday, and say, ‘Well, if they can do it, so can I.’ ”

Within the walls of Fender Flagship Tokyo, the product and the marketing are wrapped so tightly together that two have almost become one. Climbing a central spiral staircase while surrounded by scores of photographs featuring several generations of influential musicians makes it clear: this is a veritable cathedral of guitar whose express purpose is to convert curiosity into sales ringing loud and clear at the ground-floor cash register.

For an amateur musician and professional music listener, attempts to resist the siren song of what’s housed here take on a physical dimension: our fingers tingle in the presence of hundreds of the most alluring musical objects in the world.

This is no hands-off museum, either. Instead, they’re all treated as living objects, meant to be picked up and plucked: plenty of headphone sets installed near cushioned seats encourage private play-testing for your ears only, while for those who like it loud there’s a soundproofed room full of Fender amplifiers where one can plug in, turn up and let rip.

To distract ourselves from that tug of desire while stalking the floors with Cole, we observe that the language used can veer toward the highfalutin: the custom shop on the top floor is named the “dream factory”, while displayed prominently beneath a range of signature guitars is an unattributed quote that clangs in the ear like a bum note in an otherwise elegant solo: “Artists are angels – we give them the wings to fly.”

If your eyes rolled skyward on reading those words, you’re not alone. Yet it’s not until months after our visit, while researching this article, that it becomes clear this quote belongs to Leo Fender, and those words have formed the company’s guiding vision statement for decades, including long after the man himself died in 1991, aged 81.

One guitar store owned by one manufacturer in one city isn’t likely to shift culture all on its own – but, similarly, neither did the company founder know what he was doing all those years ago when he first shaped the Telecaster in 1950, then refined the design four years later with the Stratocaster, which remains among the most sought-after musical instruments seven decades later.

Fender, the man, couldn’t have known that talented players such as Kurt Cobain and David Gilmour – as well as Australia’s own Ian Moss and Tash Sultana – would use his tools to craft works that would resonate across continents, both then and now.

Fans of Nirvana, Pink Floyd and Cold Chisel mightn’t know which instruments were played on their favourite songs or albums – just as lovers of AC/DC and Tool mightn’t give a toss that Young and Adam Jones of those respective bands preferred shredding on axes made by another famous brand, Gibson.

Electric guitars may not be a renewable resource but talent is.

Part of the thrill of following popular culture is in its unpredictability. The Beatles and their rock ’n’ roll contemporaries were anonymous outsiders right up until they weren’t, and what earned their reputation – and our adoration – was their facility to write and play music that moved us.

As a species we crave novelty in our entertainment: nothing is static, and constant evolution is what keeps us interested in what’s coming next.

Although it appears the electric guitar is out of fashion, this could well be the year that changes.

Why not? As history shows us, all it takes is a few clever artists with a handful of great songs – composed, performed and recorded in the right place at the right time – to shift culture.

Maybe the children of today’s fanatical music listeners raised on a soundtrack of electronic, hip-hop and country will be itching to shake off their parents’ stodgy tunes by plugging into something else.

Perhaps that something sounds a lot like going back to the future: a rough-and-ready amplified electric six-string, lovingly played by passionate artists itching to sprout wings and take flight.

The writer travelled to Tokyo with the assistance of Fender Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout