Long shadow of Slim: Australian country music 20 years on from Slim Dusty’s death

Playing to a crowd of 114,000, all eyes were on Slim Dusty in one of his final major performances. Twenty years after his death, who is driving the multimillion-dollar Australian country music industry today? | LISTEN

Just before the spotlight hit Slim Dusty, the musician had a moment to himself. He drew in his breath, steadied his hands, then looked up and never looked back. Out he strode, the undisputed king of Australian country music, wearing his distinctive turned-down Akubra hat and a dark overcoat.

With an acoustic guitar slung across his shoulder, the man born Gordon Kirkpatrick opened his mouth, and from it emerged a familiar melody attached to a timeless story from the bush, set to strummed guitar chords.

For three minutes, the crowd of 114,000 packed inside Stadium Australia was dialled in to Dusty’s timing and phrasing, and joined the musician in full voice as he worked his way through Waltzing Matilda, the poem Banjo Paterson had composed in 1895 and that Dusty had recorded and released in 1960.

It was a night of high emotion as jubilant Sydneysiders – and millions more watching beyond the city limits – celebrated the closing ceremony of the 2000 Olympic Games.

As the 73-year-old singer-songwriter strummed, he walked from the outside of the running track, through the crowd of athletes towards the centre of the arena to join on stage the performers who had preceded him. Beside him, swaying and singing, were the likes of Kylie Minogue, Jimmy Barnes, Colin Hay, Peter Garrett and Darren Hayes, as well as globally familiar Australian faces including Elle Macpherson, Greg Norman, two Bananas in Pyjamas and Paul Hogan, dressed in full Crocodile Dundee get-up.

But all eyes were on this Australian country musician, for it was he who had been handed the proverbial torch to send the nation – and the huge international TV audience – off with a song, just before the fireworks bloomed overhead.

If that had been Dusty’s final act of public performance, it would have been a fitting apex from which to survey the gradual ascent of his beloved country music. But that night of October 1, 2000, wasn’t to be Dusty’s last hurrah, for he had in him almost three more years of songs and stories to share. With his wife and creative partner, Joy McKean, he had spent five decades taking country music to the people of Australia, from town to town.

Of that night in Sydney, McKean later wrote in her 2014 book Riding This Road: “The whole massive crowd took up the refrain; the electricity from those thousands of people crackled in the night air. I have never, ever felt anything like it in my life. I stood in a daze watching my husband and willing everything to go right for him … and it did.”

When Dusty died from cancer on September 19, 2003, he was 76 and had been working on his 106th album for record label EMI. Of course there was a historical significance to that date, given the size of the lives he and McKean had led together in public: September 19 was the 49th anniversary of his first touring concert with his wife, in 1954. His widow accepted the offer of a state funeral, held 10 days later at St Andrew’s Cathedral in Sydney. There were songs to be heard there, too, including his signature tunes.

Slim’s and Joy’s daughter, Anne Kirkpatrick, tells Review: “Everyone sang A Pub With No Beer, including [prime minister] John Howard – which was a moment,” she says with a laugh.

“But I have to tell you, I think my proudest moment – gosh, I’m going to get emotional, now – was seeing Dad walk out with his guitar, singing Waltzing Matilda at the 2000 Olympics closing ceremony.

“He started off as a boy growing up on the NSW North Coast, on an isolated, small dairy farm in the Nulla Valley – climaxing his career with that? Incredible.”

Almost two decades on from the king of Australian country music’s death, what do we see? Does that bush balladeer in the Akubra appear as a man out of time? Is he an anachronism from a simpler moment in our collective history, when the residents of small-town Australia thrilled to the travelling Slim Dusty Show?

Or do we see him – and McKean, his no-bullshit partner and fellow pioneer – as essential contributors to a national songbook that continues to grow, within a sector that generated an estimated $574m in revenue at its last industry-wide survey in 2018?

The story of our country music is approaching its centenary. In the 1930s, it began to make inroads into the space occupied by popular Hawaiian music that dominated the era; into the next decade, plenty of regional radio programs featured country, or “hillbilly music”, as it was then known. The songs tended to follow simple folk structures, generally led by acoustic guitar and voice, and coloured by instruments including fiddle, banjo and harmonica.

Lyrically, these were tunes broadly about people living, loving and dying in Australia, and a connection to the land was a songwriting asset to be prized and celebrated. By the early 1950s, it was possible to attend a country music concert in a suburb of Sydney almost any night of the week. Country or “hillbilly” artists had become accepted as professional performers on the scene – but not for long.

“When rock ’n’ roll emerged, it became fashionable to look down on country music as uneducated and unmusical, beneath the dignity of any real musician,” McKean wrote in her 2011 book I’ve Been There (and Back Again). “The country music singer was an oddity to be tolerated with amusement in an urban environment. Furthermore, to dress in country clothes such as riding boots and a wide-brimmed hat was to invite ridicule; only ignorant hicks from the sticks would be seen dead in such things.”

As McKean told it, the popularity of rock sent country music performers out of town, on to the roads of the nation and directly to the people who wanted to hear it.

“The fans in town kept quiet and hoped they’d still be able to find some new country records around. It must have been a blessing for them when A Pub With No Beer helped make country music acceptable again,” she wrote, referring to Dusty’s 1957 hit, which became the first gold record released by an Australian artist.

Written by Gordon Parsons and based on an Irish poem that told of a parched stockman’s disappointment at finding a dry watering hole, the song reached No.1 here and in Ireland, and No.3 in Britain in 1959. It became a foundation for Dusty’s career and a broader understanding that country music could exist in parallel with popular music of the day, even if such songs rarely troubled the top of the charts.

Since then, tastes have changed considerably, not least when it comes to matters of refreshment selections. In March, when Review visited the CMC Rocks QLD festival south of Brisbane, we were informed that, on the first night alone, bar staff had sold 40,000 frozen cocktails at $15 a pop. (Among the country songs yet unwritten: A Festival With No Frozen Cocktails.)

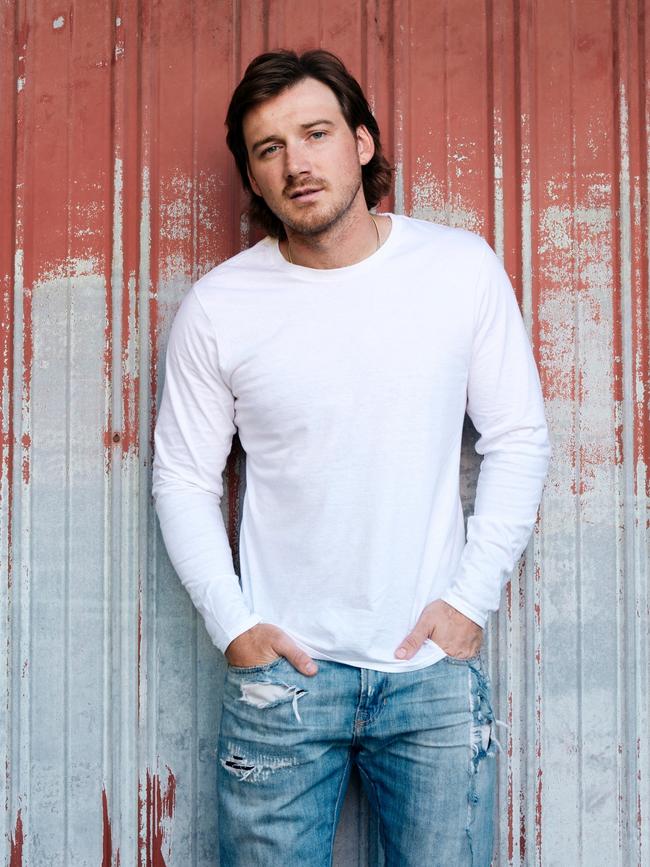

Musical tastes have changed, too: the headline act in March was Morgan Wallen, a 30-year-old US artist whose multi-level stage production more closely resembled a stadium rock gig – complete with pyrotechnic blasts – than anything Slim and Joy might have imagined could be considered a country music show. The scale of the production made sense, for Wallen and his six-piece band regularly fill stadiums of 50,000-plus in their homeland, which must have made the CMC crowd of about 23,000 feel comparatively intimate.

At country gigs large and small, the songs are always at the centre, of course: none of it makes sense without these two-to-five-minute slices of life set to music. But country music is not just about the stories: it’s big business. According to a mid-year report issued by music data provider Luminate in July, Australia is now the No.3 market for country music in the world, behind only the US and Canada.

During the first six months of this year, the top 500 country songs were streamed 1.1 billion times by Australian listeners, with overall streaming numbers up 55 per cent compared with June last year.

Among popular country tracks today, a few traits catch the ear: a strummed or finger-picked acoustic guitar tends to drive the chord progression, and you’ll inevitably hear electric guitars stacked atop the acoustic base, showcasing clean or dirty tones, depending on the mood of the song. As for the other instruments, you’re just as likely to hear hip-hop style programmed beats as an actual drummer; same with the bassline, which may be synthesised or may have been played by human fingers on four strings.

Tune into a country music radio station or streamed playlist today, and you’ll hear well-enunciated lyrics that most often concern found love, lost love, booze, or aspects of all three. The words are set to melodies so memorable and accessible that, if you’re paying attention, you’ll probably be able to sing along by the time the second chorus rolls around. Call up the most streamed tracks by Wallen or his contemporary, 33-year-old Luke Combs, and you’ll hear all of the above. Thanks to big releases by the likes of Wallen, Combs and Taylor Swift’s re-recorded versions of her early-career albums, the genre currently is cresting a new peak of popularity.

Despite the perception that country audiences skew older, artists such as these – and their huge streaming numbers – are bucking that trend and fuelling a renewed interest among younger listeners. According to data sourced by ARIA, country artists in the top 100 album chart this month accounted for 12.8 per cent overall, up from 3.9 per cent a year ago, and only 2.1 per cent of the overall chart in September 2018.

When Review attended a sold-out Combs concert at the Brisbane Entertainment Centre last month, it was an unusual experience to be among 13,000 or so Australians – many of them in their 20s and 30s – singing along to every word of a 2017 song whose title referenced Houston, the most populous city in Texas.

Yet even if this polished, glossy product is not your cup of tea, songs such as Combs’s Houston, We Got a Problem exhibit nothing if not canny songwriting and arrangement led by a universal sentiment of missing the one you love. If you’ll let them, songs such as these are liable to worm their way into your brain.

Why are these aspects of American country music being analysed here, in a story that began with the king of Australian country music lit by a spotlight on the nation’s biggest stage? Like it or not, that’s simply the way the cultural exchange flows today, thanks to the influence of mass audiences on platforms such as Spotify, YouTube and TikTok.

If local artists wish to build a sustainable career, they’d be fools to ignore what’s popular here and abroad. And it just so happens that, today, American country music is an unavoidable juggernaut whose sounds appear regularly near the top of the ARIA chart, and on commercial radio and streaming playlists.

It’s no small thing for Wallen and Combs and others to travel the world and play to large crowds, either, and it hasn’t happened overnight.

Talk to anyone familiar with the story of country music since Dusty’s death in 2003 and they’ll point to the efforts of a man who saw the potential for North American acts to find a footing in this market.

“It all goes back to the late Rob Potts, who had a dream that he brought to me well over 20 years ago, when he was on the board of the Country Music Association in Nashville,” concert promoter Michael Chugg tells Review.

That dream was a festival named CMC Rocks, showcasing American country acts alongside Australians, that began in 2008 in Thredbo, NSW, and has been held at Willowbank Raceway in southeast Queensland since 2015.

“He’s regarded in Nashville as being the person who built the bridge between Australia and Nashville,” says Susan Heymann, chief operating officer at Frontier Touring. “He came to Michael with this concept, and Rob sadly passed away suddenly in a motorcycle accident in 2017. It was two weeks after CMC went on sale, with Luke Bryan headlining. It was the first time we sold out on the [first] day; he was so thrilled, and it was tragic to lose him when the festival was just getting going.”

Potts lives on as a symbolic north star for how Chugg, Heymann and their colleagues working on the annual festival aim to represent the genre, its community and its artists. Expansion plans are under way, too: in November, Frontier Touring will debut an event named Ridin’ Hearts at showgrounds in Sydney and Melbourne, featuring US artists including Bailey Zimmerman, Danielle Bradbery and Sam Barber.

“CMC is like a country version of Splendour in the Grass: it’s young, it’s contemporary, it’s the artists that are selling out arenas and topping charts, and punters who like to camp,” says Heymann. “Ridin’ Hearts is a bit more like the Laneway [Festival] of country music: an urban, single-day event with young up-and-comers, and we’re hoping to host artists that will be the next arena headliners before they get there.”

Potts’s son, Jeremy Dylan, works in the industry as a promoter, agent and manager, and has been director of CMC Rocks QLD since his father died in 2017.

“I think the one thing that country has over a lot of other types of music is that you can still make a big dent in building your career through regional touring, and working really hard at connecting with that market in a deep way, and that’s a very loyal audience,” Dylan, 33, tells Review. “I’m more optimistic now about the immediate future of local country music, and the careers of the really talented artists here, than I have been in a while.”

Though some may decry the influence that American performers have over the popular version of the art form today, it’s worth remembering some of our biggest artists were themselves moved to begin playing after hearing songs recorded in that part of the world.

Keith Urban was 22 when he won the Tamworth Star Maker contest in 1990, but he had his sights on larger prizes. He moved to Nashville and worked hard to crack that market, eventually breaking through in 1999. As our biggest country music export, he’s the only Australian artist capable of filling arenas both here and in the US. Urban’s style involves blending aspects of modern pop, rock and R&B, which is a far cry from the approach taken by Dusty and McKean, and those who came after them.

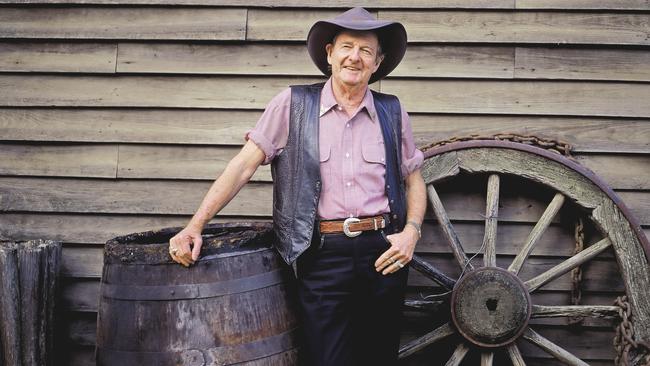

“I was taken in by folk music originally when I was at boarding school in Melbourne,” John Williamson tells Review. “In the early 1960s, folk music was huge, and I just loved the way Americans sang about their country. At that stage I really hadn’t listened that much to what [Australian artists] Buddy Williams, Slim and Stan Coster were doing. To me, their music – and what I’ve followed on from, really – is our folk music. It’s our stories about life in the bush.”

At 77, Williamson has scaled back his touring but continues to perform occasionally and tends to sell out theatres wherever he goes, including at the annual Tamworth Country Music Festival.

When the singer-songwriter and his band take the stage at the Tamworth Town Hall each January, it is an unforgettably moving experience to be among an all-ages crowd, witnessing him singing the likes of True Blue, Raining on the Rock and Waltzing Matilda – the latter of which he performed at the opening ceremony of the Sydney Olympics in 2000, too, in a move that mirrored Dusty’s closing performance.

“To me, Waltzing Matilda was our first country song,” he says. “If you listen to that, in today’s country music genre, with the American influence, it’s nothing like that. I guess it’s a folk song, but it told a great country story.”

Authenticity is sometimes co-opted as a marketing buzzword but among country artists, more than perhaps any other musical genre, demonstrating respect for those who came before you is a cultural norm. To shun the stars of yesterday is a cardinal sin.

Like Dusty, Williamson’s influence looms large: at a sold-out concert at Brisbane’s Fortitude Music Hall last month, the song chosen to play over the PA as the lights went down was True Blue.

As one, the 3000-strong crowd sang along before the headline act – Newcastle-born, Nashville-based artist Morgan Evans, 38 – walked out with his band. Mid-set, Evans performed a solo guitar take on Waltzing Matilda; he also invited Williamson to join him in a duet at his Sydney Opera House concerts earlier this week, too.

For Kirkpatrick, Dusty and McKean’s daughter, the upcoming 20th anniversary of her father’s death on Tuesday will be a particularly sad one, for McKean died of cancer in May, aged 93.

“It’s been a really hard year,” Kirkpatrick says. “In the latter years, after my dad went, Mum and I did a lot of road trips, and we were very close. But I’m so heartened by the amount of respect and gratitude given to Slim and Joy for what they created, and for opening the way for so many of the younger performers. They realise that Mum and Dad did the hard yards.”

Asked what she hears in the genre’s popular sounds today, Kirkpatrick replies, “Country music is evolving, and it’s got to: to stay viable, you’ve got to embrace change. It’s great to see people like Fanny Lumsden going back to the grassroots and embracing touring in country halls, which Slim and Joy did.”

Lumsden is an independent artist from southern NSW, near the Snowy Mountains. At 36, she has become one of the most popular country performers, with her accolades to date including an ARIA in 2020 and a five-award sweep of the Golden Guitars in 2021. Her Country Halls Tour began before she had visited Tamworth at all, and it was born out of naivety and a can-do spirit.

“I didn’t know about how other people toured; I just did it, and started it because it made sense,” she tells Review. “I wanted to tour and share my songs. I grew up in the country, and I knew these venues existed, and I knew how to get those people to come out to venues; I knew how to motivate them and make it theirs, not mine.”

Since 2012, Lumsden and her band have performed at more than 200 halls around Australia: they provide the PA system, sound, lights and music, and a local organisation provides the hall, an enthusiastic community base, and all manner of volunteers to staff the door, barbecue tongs and icy tubs behind the bar.

“If you live six hours from the city, this is exactly what happened to me: I never went to live music because I wasn’t going to pay $1000 to fly down and back, and get accommodation,” she says. “I feel like regional events are more important than ever. I think it has a real future.”

With her band, Lumsden will soon announce the resumption of the Country Halls Tour in regional NSW for its 10th anniversary, starting at Goolma Hall and ending at Gundy Memorial Hall, as well as Tamworth (January 27).

It speaks to the health of country music in Australia that the chance to see a great concert is never too far down the road, whether it’s an indie performer in your small town, a band plugging in at your local pub or a global superstar on a big stage near the centre of our capital cities.

Today, neither country music singers nor their fans are considered oddities to be tolerated with amusement in an urban environment, or seen as hicks from the sticks. Instead, they look just like the rest of us.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout