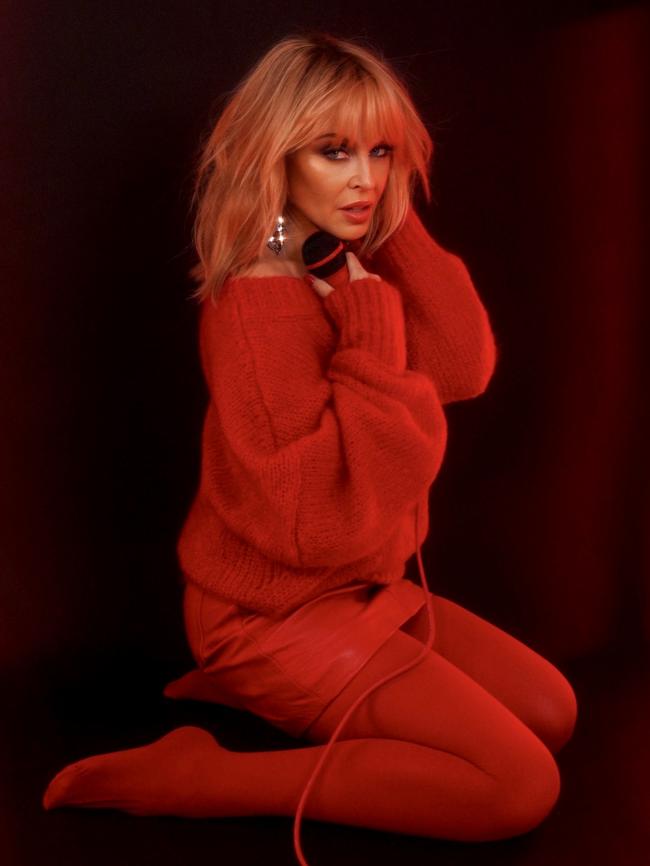

How Kylie Minogue became an enduring and beloved gay icon

Could Kylie Minogue’s willingness to tackle adversity be the secret to her intriguing status as a longtime icon for the gay community?

With her back to the audience, Kylie Minogue first came into view while standing on a rising platform with her arms by her side. As she was slowly spun to face the crowd, the singer could not help but let a smile pass across her face as she raised her hands and began to move, just like the thousands of dancing bodies in front of her.

Wearing a frilly pink dress and high heels while flanked by about two dozen male and female dancers, Minogue made her debut performance at Sydney’s Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras on March 6, 1994. As was customary in that era, Minogue was at the party held at the Royal Hall of Industry to perform one song only, a single from her third album Rhythm of Love. “What do I have to do to get the message through?” she sang into a hands-free microphone. “How can I prove that I really love you, love you?”

Amid a din of thumping bass, a bouncing keyboard chord progression and airless drum machine hits, her dancers stripped to their pink underwear and onstage pyro detonated as an extended version of her 1991 single wound its way to a euphoric conclusion.

“Thank you so much,” Minogue told the crowd. “I’m so honoured to be here tonight to join you in your celebration. And I thank you from the bottom of my heart for all your support. Happy Mardi Gras!”

Four years later for the 20th anniversary of the annual community event, the singer came into view at the same venue while standing on another rising platform, this time wearing a tiny red dress and wielding a pitchfork to perform Better the Devil You Know, the opening track and lead single from Rhythm of Love.

Soon, she was surrounded by dozens of shirtless male dancers in tiny shorts and devil horns who turned their bodies and hands toward the central figure as if deferring to a queen. Halfway through the song, Minogue caught her breath then announced, “I’d like to say happy Mardi Gras to you all. Twenty years: a celebration of remembering, and personally, a very big thank you to all of you for your support and your care over the years.”

At both of these events, the pop singer was an unannounced performer, as the Royal Hall of Industry could only hold about a quarter of the 20,000 or so people who descended on Sydney for the Mardi Gras Party each year. On each occasion, the sheer surprise of her appearance could partially explain the ecstatic crowd response, at least at first. But the sustained cheers directed her way hinted at a much deeper connection with the LGBTQI community, which evidently viewed her as much more than just a pop singer.

When Review asks Minogue on a Zoom call from her home in London why those two single-song sets at Mardi Gras in 1994 and ’98 were so important to her at the time, she replies: “I mean, it was the biggest celebration. It was an amazing thing; there’s no question, if I could be there and get enough of the team to do it. You’re never prepared for how hot and sticky and crowded it’s going to be, and the energy? I’m surprised the roof doesn’t come off the venue. I mean, it’s just an absolute love fest. I didn’t think twice: it was important for me to be able to be there and share the love.”

After making the leap from television actor to pop singer with her 1988 debut album Kylie and its hit singles, including I Should Be So Lucky and The Loco-Motion, Minogue’s stunning chart and commercial success – with global album sales of several million copies – proved that a large swath of the population was well and truly on her side, both here and in Britain.

The press, however, was not. Derided as a “singing budgie” who simply parroted songs penned and produced by the powerhouse British music team Stock Aitken Waterman, Minogue was an easy target for small minds with large audiences. Tall poppy syndrome was alive and well, and kicking Minogue for her perceived faults – and her willingness to try something different to the TV acting roles she had previously been known for – became something of a national sport for some sections of the media.

While working in Sydney early in her music career, Minogue learned of a drag show known as “The Kylie Night”, held at the Albury Hotel on Sydney’s Oxford Street. The singer – then about 20 years old – was keen to check it out incognito, but her manager nixed the idea. That was the first time she recalls becoming aware of the LGBTQI community’s fascination with her, although the specifics of that enduring fascination elude her.

“I don’t know the answer,” she tells Review. “I almost don’t want to know the answer, because it was so organic, and I treasure it even more so for that.

“I guess part of it’s the music,” she adds. “Part of it may have been – this is a theory I’ve explored – that I wasn’t always given the easiest of times back then. And I wonder if part of that coming together was an understanding of what it is to just not be accepted for who you are. I would really have to ask some of the people who were there, and what led them to kind of adopt me.”

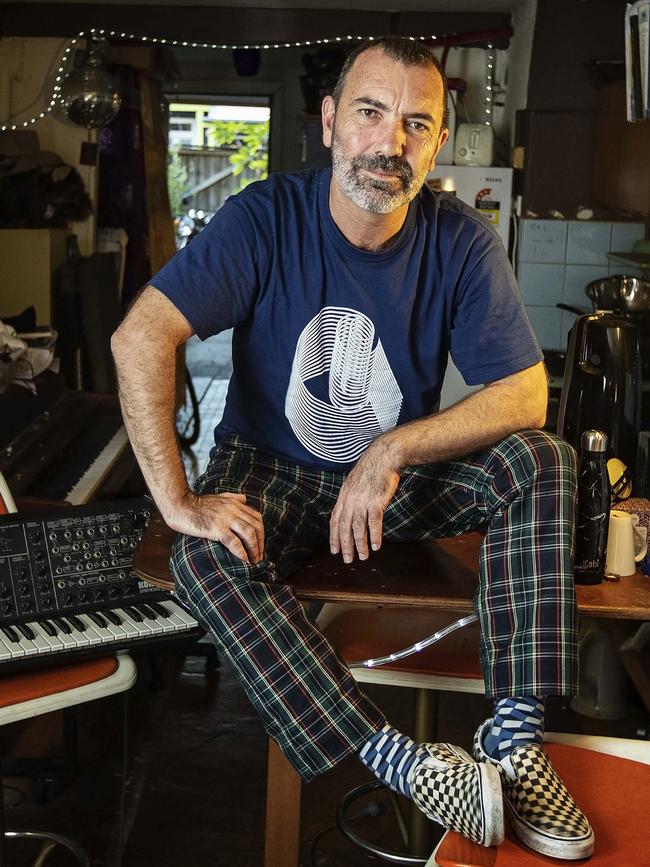

When Sydney musician Paul Mac went to his first Mardi Gras in 1985, he was not yet out as a gay man and felt overwhelmed by the possibilities offered by an alternative world where overt displays of sexuality were the norm. Since that tentative first experience, he has become a proud member of both the LGBTQI community and the national dance music scene, first with ARIA Award-winning electronic music duo Itch-E and Scratch-E then under his own name. Having attended the event most years since 1985, he has watched and listened with great interest as his peers have taken Minogue’s music and public persona to heart.

According to Mac, her exceedingly high esteem was sealed with those two party slots in 1994 and ’98.

“Playing Mardi Gras is a huge deal,” he says. “It really is: it means that you care, even if you’re huge and you’re really busy and you’re mega successful. Mardi Gras doesn’t have a lot of money; it’s a community event. Sometimes you might do it to promote your new album, but sometimes you just do it because you want to do it, and acknowledge your rather large gay fan base.”

“There is always that tired old trope that the gay audience is loyal: if you show your love to them, even in the down times – like Judy Garland or Cher, or anybody who’s been around forever – there’s that idea that the gay community loves a survivor and a trouper, and somebody who just keeps going through adversity.

“I don’t want to speak for the whole gay community, but there was that whole disco period of (Gloria Gaynor’s 1978 single) I Will Survive, and even the tradition of drag is sort of emphasising or exaggerating what it is to be an empowered female, which comes from being the underdog throughout history,” he says. “And despite marriage equality, there’ll always be the sense that gays find strength in unity and relate to music that I think plays to that strength of character, which is often embodied in a female diva.”

When Review puts these notions as possible contributing factors for the community’s love for her to Minogue, she replies, “I know that is one of the traditional reasons. I remember years ago, making a joke about that; an aside saying, ‘I haven’t had much tragedy in my life – except for hairdos’. And I must have been quite young when I said that, because I think as you get older, you realise there’s stuff you’ve got to get through.”

Stuff like her well-documented breast cancer diagnosis midway through her Showgirl tour in 2005, which forced her away from the stage to undergo treatment before re-emerging to complete the tour toward the end of 2006.

“So now that I am older and have had more challenges, it kind of made sense,” she continues. “I remember at the time when the press were really harsh on me. It didn’t seem like the public were, but the press were.

“I don’t think it would happen today, but I think it was oftentimes just not nice; borderline a bit cruel, or just unnecessary.

“Even starting being in Neighbours and making the move into music (the response was), ‘How can you do that? You’re an actor, you’re not a singer’. That’s really what I can link it to, aside from the music. But maybe it was just an unknowing; maybe it was just a sense, as well, that we like each other.”

Certainly there are some business smarts attached to this mutual love-in: from any management or record label perspective, if a small but important segment of the community latches on to your artist, it’s outright foolish to stand between the two. Instead, better to foster that relationship by adding a little fuel to the fire from time to time – as Minogue did by returning to perform a 20-minute set at Sydney Mardi Gras in 2012 – lest fickle audiences move elsewhere.

Since she made the switch from acting to music, though, few could accuse Minogue of surrounding herself with inept people. In her first meeting with Mushroom Records in 1987, her father Ron – an accountant by trade – was her representative, asking hard questions about potential financial deals and ensuring that his daughter would be duly rewarded were her nascent musical career to take off. It did, of course, and she was indeed duly rewarded, as was her longtime record label.

In his 2015 biography of Mushroom Group chairman Michael Gudinski, author Stuart Coupe noted that Minogue made more money for the label than any other artist Gudinski had worked with, “by a very long shot”. When this is put to him, Gudinski tells Review: “I’d have to say yes, but not as emphatically as Stuart said in that book; I wouldn’t say it was so much more (than others).”

As for the deep and long-lasting connection with the LGBTQI community, Gudinski says: “The thing that’s always been very interesting to me is how she’s got three or four generations of fans. People have grown up with her, and like everyone she’s been through ups and downs. I think that she’s got a very genuine love relationship with not just gay people, but she’s most probably our greatest export in the sense of longevity.”

Central to it all, though, is the quality and consistency of her music. Far from retreading the same artistic ground, Minogue has instead traversed a wide stylistic path within the broad spectrum of pop music. “She’s found a really cool way of expressing what she wants to express that resonates with her audience,” Mac says.

“Sometimes it crosses over to a wider one and is hugely successful – like (2001 single) Can’t Get You Out of My Head – and other times it tanks, and doesn’t. But that’s what I love about her: she never gets desperate, there’s no feature (track) with (US rapper) Cardi B.

“On the other hand, Madonna is slavishly trying to get on the f..king bandwagon as it’s leaving the kerb – whereas Kylie just sort of sits adjacent to it all and does her thing.”

That sense of running her own race continues with Disco, her 15th album, whose blunt title describes the dancefloor where these songs are aimed, even though much of it was assembled remotely during the pandemic, with Minogue recording most of the vocals at her home for the first time. Notably, she is credited as co-writer on all 12 tracks for only the third time in her career, following 1997’s Impossible Princess and 2018’s Golden.

As for the notion that the gay community loves a survivor? “I think Kylie certainly fits that trope now,” says Mac. “All of that would be nothing if she kept writing shit, formulaic songs – but that’s why, when she comes out with (recent single) Say Something, I think, ‘Ah, she is vital; she is still evolving, and she is still offering something new’. She is listening to what’s around her and learning from it, but putting it back through her own Kylie filter to make something really incredible out of it.”

While working on Disco remotely with writers and producers, one of Minogue’s favourite reference points was Earth, Wind and Fire, the multigenre-spanning US band whose performance videos she would occasionally call up for inspiration. Founded in 1969 and still touring today – pandemic aside – the group is one year younger than 52-year-old Minogue, who speaks glowingly of the band’s long-running career.

“I totally admire that,” she says. “I mean, I’ve been now (active for) just over 30 years, and depending which side of my brain I’m talking to, one side is, ‘I just love the amount of experience that I’ve been able to get from all of that time’, and the other side’s going, ‘There’s so much more to do – you don’t know anything yet!’

“A band like that, with such a long career, and just the tenacity to keep at it, trying new things, still appealing to your older fanbase who want to hear the hits – I guess I’m kind of in the middle of that now, and I’m enjoying it. I am especially enjoying it, because I still get to do new music.”

At her first Mardi Gras performance 26 years ago, Minogue sang a song whose emphatic chorus wondered what she had to do to get a message through.

Today, after 33 years and 15 albums as a recording artist, what does she have to do to prove to the LGBTQI community that she really loves them? Nothing. They already know, just as they’ve known for decades.

Disco is released on Friday, November 6, via Liberator Music/BMG. A ticketed online event, Kylie: Infinite Disco, is streaming at 8pm AEDT on Saturday, November 7.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout