Colin Hay on why you’re probably wrong about Down Under, his biggest hit

Forty years after its release, Men at Work’s Colin Hay reveals the true meaning of hit song Down Under and the irony in its misinterpretation: “A lot of people never picked up on what the song was actually saying.”

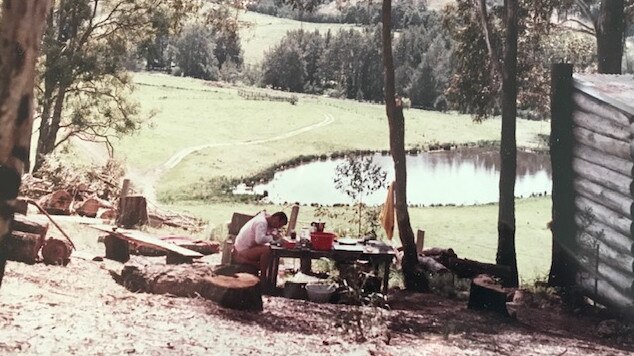

There is a bush block in coastal NSW that has played a major role in the life of one of Australia’s most significant singer-songwriters, and after hundreds of songs, thousands of performances and millions of record sales, it continues to flash in his mind today.

Few people knew Colin Hay’s name, voice or story back in 1978, but that was OK: the 25-year-old had a plan and a preternatural sense of ambition. He was confident that, in time, he and his talents would be noticed and remembered.

The bush block is near the town of Bermagui and was owned by his then girlfriend, Linda Cuttriss, who became his first wife. She bought it for $9000 in 1976, after being inspired by some hippie friends who had also bought land nearby with the intention of avoiding the real world for as long as possible.

That idea appealed to the young musician who had barely $9 to his name, and he loved the spot where there was nothing else to do but play acoustic guitar and sing.

Getting there meant hitchhiking about 650km from Melbourne, and just ahead of him – just out of sight – was a lightning strike of global fame that would change his life.

Asked how often he thinks back to that slice of paradise, Hay replies with a smile. “Oh, most days,” he says. “I enjoy those pictures that dance in my head of different places that I’ve been, that I love. There’s parts of NSW that are pretty, and I think I romanticise that a lot, just because of the fact that it’s still one of the great secrets of the world, the Australian coastline.

“People flock to beaches all over the world, and a lot of the beaches in Australia are pretty unparalleled. Not that I spend a whole lot of time at the beach – but I think it creates some kind of openness, internally.”

It was a decent hike from Melbourne to Bermagui, but no mind. Born in 1953, Hay and his family had already upped and left their home on the southwest coast of Scotland, arriving as immigrants in 1967 and settling down in the great southern land. To the red-headed teenager, it was an eye-opening trip that foreshadowed a life of near-constant motion.

A few weeks at that bush block, honing his musical craft and testing that soon-to-be famous voice beneath the gum trees, worked wonders.

It was there he wrote a song titled Who Can It Be Now? It took him about half an hour to pen the chords and chorus melody, and when he played it to Linda, she said: “That’ll be your first hit record.”

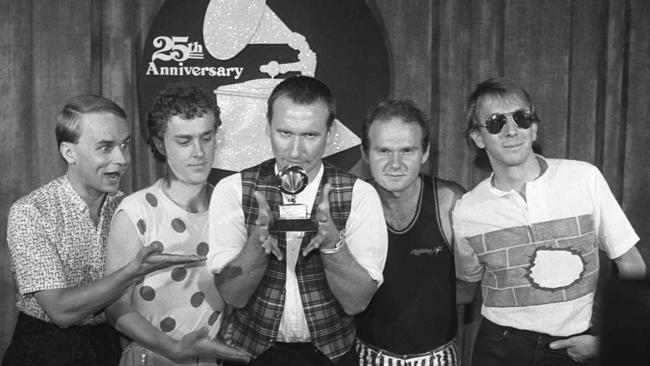

So it was: three years later, the song opened the debut album by Men at Work, the rock ’n’ roll band he formed in Melbourne with Ron Strykert, Jerry Speiser, John Rees and Greg Ham. Business As Usual sold an estimated 10 million copies and spent 15 weeks at No.1 on the US Billboard chart, a stunning feat at the time and perhaps even more impressive today.

It was the second single from the album, though, that cemented the band’s place in the pop pantheon. With a keening voice, Hay asked something in Down Under that was far more than an easy rhyming couplet. “Can’t you hear the thunder?” he sang, and few pop choruses have contained a question so resonant. As he’ll go on to explain, most people missed the point of the song entirely.

A habitual travelling performer for four decades and counting, Hay recently has had plenty of time to think, write and record at his home in Topanga Canyon, California, which he shares with his wife and fellow singer Cecilia Noel and their dog, Rico.

In the early months of the pandemic, he was a contributor to Review’s Isolation Room video series, where he performed the title track from his 2015 album Next Year People while sitting on his brown couch. The song was inspired by a Ken Burns documentary about the Great Depression, which featured the stories of people who found themselves in tough situations but continued to do the same thing year in, year out, waiting for good things to come their way.

Once he began writing about the touchingly naive optimism he saw in the documentary, Hay realised his lyrics could just as easily apply to himself. Like many performing artists, he had asked himself countless times across the decades: are my ticket sales going up? Are more people coming to see me play, or am I kidding myself? Am I doing the same thing because it’s just a habit?

“And I still don’t really know the answer to that question,” Hay told Review in April 2020. “Some people think you’re crazy when you just keep going on the road – and they may have a point. But I tend to be someone who likes to live in the moment, and I’m a naturally optimistic person who thinks, well, if you take care of the present, the future takes care of itself.”

When Review reconnects with Hay on a video call in August, the ardent road-dog is once again traversing the US. Much of the rest of the year will be spent in his preferred mode of taking his songs to the people, both in the US – where he is presently touring Men at Work with his Los Angeles-based band – and in Australia, where he will play a run of solo shows in November.

The Covid-enforced break in touring meant that Hay was available to pop up on Australian television screens in a couple of high-profile appearances, albeit remotely.

The first was on Anzac Day 2020, when he performed a duet with Delta Goodrem during the Music From the Home Front special, hastily arranged by the late Michael Gudinski and his team at Mushroom Group.

Then, as part of last year’s AFL Grand Final pre-game entertainment, he said g’day from a sunny Californian beach, acoustic guitar in hand, before the focus shifted to singers inside Perth’s Optus Stadium including John Butler and members of The Waifs and Eskimo Joe.

On both occasions, Hay sang his best-known song: the one co-written with guitarist Ron Strykert, whose chorus contains that mysterious five-word question.

Unusually, it’s a composition that has been raked over the coals in a courtroom: in 2010 the Federal Court ruled that Greg Ham’s flute part in Down Under infringed the copyright in the song Kookaburra Sits in the Old Gum Tree.

A judge ordered that 5 per cent of royalties from 2002 onwards be paid to publisher Larrikin Music – an amount that Hay has estimated at $100,000, and dwarfed by the millions that both sides spent fighting the court case. (“I believe what has won today is opportunistic greed, and what has suffered, is creative musical endeavour,” he said in a statement following the ruling.)

Asked what it’s like to have that song in his kit bag – to be forever known as the “Down Under guy” – and whether he always wears it with pride, Hay responds thoughtfully, and it’s worth quoting him at length.

“I really love the song, and it lives inside me,” he replies. “At the time, women did glow to me; I was at that age, and there were lots of glorious women around. And it seemed that the men, as far as I was concerned, if they were wearing a suit and a tie, they were part of the ‘straight world’ – and I just didn’t want to be part of the straight world.”

“The song was satirising, to a large degree, the unconsciousness of a lot of people who are walking around that continent, and unaware of how amazing the place is, and the fact that we are supposed to be caretaking this place.”

“At that particular time, when I wrote the lyrics for the song, I had a lot of fear and trepidation about coastal desecration, and the selling-off to foreign entities of bauxite, or everything that was under the ground.”

“It just seemed like, if we could grow it or it was there, we would sell it to whoever wanted it. It seemed to me like unbridled capitalism,” he says, before pausing and clarifying. “I mean, I have too many shoes to claim not to be a capitalist – but it seemed that (Australia) was being developed in a very thoughtless way. I was a tree-hugger; even back then, we were concerned about climate change in the late ’70s. That’s what another Men at Work song, Down By the Sea, is about as well (the closing track from Business As Usual).”

“To me, there was a lot of plundering going on. There was a lot of old-growth forests being threatened, and chopped down,” he says. “I was against clear-felling, and I still am. There’s only some minuscule percentage of old-growth forest and natural bushland left in Victoria, and I think it’s appalling. There’s no real need for it, either; there are alternatives.”

Of the question posed in the chorus lyric, he says: “The ‘thunder’ really was to me the environmental danger that was happening – and at that particular time, too, the Cold War was in full flight. There was a lot to be concerned about, and there still is, obviously.

“I was also a huge fan of Barry Humphries, and the character Barry McKenzie, who was writing about and satirising this whole idea of that particular Australian that we all know.

“There is something really endearing about that; it’s almost a naivety – but it can be quite brutish and quite dangerous, especially if you inject large amounts of alcohol, a lack of education, and all these other things.

“The verses were inspired by Humphries, and trying to just deflect away from what was, to my mind, a more serious topic – so people ended up drinking beer to it, and that’s OK.

“The only thing that I think is funny in a way, or slightly ironic, is the fact that a lot of people never picked up on what the song was actually saying – which is not for me to tell people, really,” he says. “You put a song out there, and it’s for other people to get from it what they will.

“It was never really supposed to be a flag-waving song – it was supposed to be something else entirely, that we have to be careful about. We have to raise our consciousness about everything, really. It’s a song that can change with the shifting social and cultural landscape, but I think it basically is rooted to the earth. I’ve played that song in Bolivia, and all over the world, and it affects people the same way.

“It’s like one of those classic folk songs that has actually become part of the DNA of the country or something, you know? It’s a simple song, and I still like playing it.”

Men at Work disbanded in 1985, the same year it released its third album, Two Hearts. Accordingly, Hay’s career was front-loaded with the experience of major success, and while his solo output has never come close to matching the chart or box-office figures of his early days in the public eye, he has also never stopped working.

Now 69, he is long past his hitchhiking days. On the day of this interview, he is in Cleveland, Ohio, on a day off, with Cecilia and Rico, amid nights spent playing Men at Work songs on a co-headline tour with Rick Springfield, which he’s pleased to report is pulling 3000 to 5000 punters a show.

Through September and October he’s out playing with Ringo Starr & His All-Starr Band across the US and Canada. Then it’s on to Australia for the first time in three years, although he laments the absence of Western Australia and South Australia dates due to issues with tour routing.

In March, Hay released his 15th solo album, titled Now and the Evermore, and last year he released a collection of covers that initially sprang from a place of sadness following the death of Gerry Marsden, the leader of Gerry and the Pacemakers.

At his home studio, Hay recorded some of his favourite songs by the likes of The Beatles (Norwegian Wood, Across the Universe), The Kinks (Waterloo Sunset) and Glen Campbell (Wichita Lineman).

Cheekily titled I Just Don’t Know What to Do With Myself – also the opening track and a Dusty Springfield cover, which was in turn later covered by both Marcia Hines and The White Stripes – it rates among the most beautiful and essential of all musical lockdown projects, up there with Taylor Swift’s pair of sparkling, surprising albums released during the pandemic.

But since he’s out touring Men at Work when we talk, that’s the music at the forefront of his mind. Given the age of the songs from those three albums, the gigs have more of a retro feel than his other shows, both solo and with his band – but he’s also thrilled to note that, after all these years, he’s playing to a lot of young people who were not yet born when those songs were first recorded and released.

“I think it’s good evidence that the songs have legs, and there’s a lot more density to the songs that perhaps people never even realised back then,” he says.

“We were never the darlings of the rock press. Because we were so successful, I think that there was a lot of people in the rock press that liked to dismiss you, and liked to pretend that what we did wasn’t that big – but it was just massive,” he says, laughing. “It was huge. What we did, and what we achieved, was really important – and in fact still is.”

That confidence he felt at 25, investing his time into writing words and melodies at the bush block near Bermagui, believing that his talents would be noticed and remembered? That all came to pass, and pop music history is all the richer for it.

Before saying goodbye, Hay pauses and asks if he can end our conversation by reading a little poem he’s written recently, while reflecting on that period of his life. It’s called Men at Work, and it goes like this:

We opened up for Fleetwood Mac

A lucky break; a sneak attack

It was only going one way back then:

To the stratosphere, and back again.

Fifteen weeks at No.1

We toured two trips around the Sun

We were kings of the world in 1981

I remember the moment it stopped being fun

The end of ’83, we were done.

It was over fast, before we’d begun

To be sure, the music remains

It floats in the air

Through the supermarkets and summer state fairs

It was a once-in-a-lifetime, but I don’t care

I got to the summit: I was there.

Colin Hay’s tour of the east coast begins in Bendigo (November 3) and ends in Thirroul (November 20).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout