How Paul Hogan, 80, plans to save the world

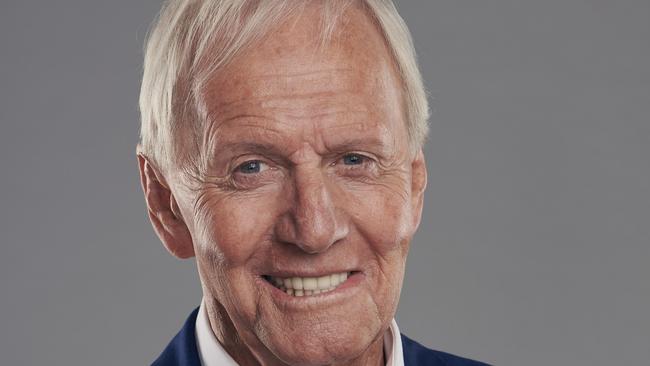

From high-school dropout with a genius IQ to ‘the living picture of political incorrectness,’ Paul Hogan, 80, reflects on his career in a climate of cancel culture.

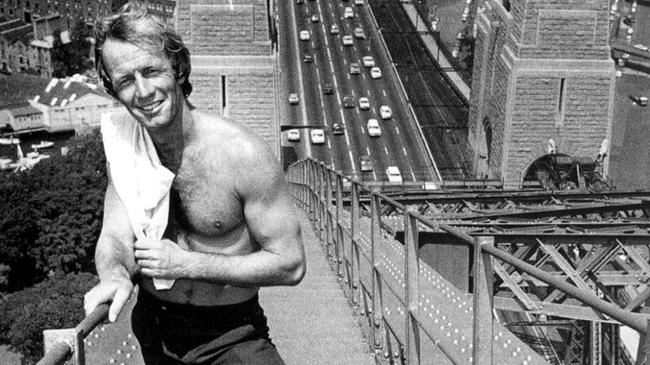

There he goes, clambering up the iconic span of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, lugging steel cable as heavy as a beer keg, free-climbing his way to the summit. Even back then, in the shaggy-dog ’70s, he was aiming high, the bloke on the bridge. Shooting the breeze with his fellow riggers, the jokers on smoko, he honed a persona he would export to the world: Paul Hogan, pub philosopher, Dada prankster. The Marcel Duchamp of bogans: Hoges.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is where it started for Hogan and doesn’t it seem like a foreign country, the past? When you could wolf-whistle and ogle girls with impunity. When Winnie Reds were good for you, life was a beach, and bikini-clad pinups were always – oops – bending over to pick up dropped objects on the hit sketch-comedy show you made with your best mate. The Seventies. The Paul Hogan Show. Light years away from this serious world.

“That was the most fun I ever had,” Hogan says now, with a soft, huffing laugh that makes you think of slippers and hot tea and reminds you that the eternal rogue is 80 years old. Today’s overheated political climate would see Hoges cancelled in a hot minute, but his creator feels no need to atone. “The shows were filled with beautiful girls but as I’ve explained endlessly, it was showin’ what melons men will make of themselves over women,” he says. “Yes that’s sexist and I apologise to the men for that.” It was comedy without malice, he insists, and besides, “the dill in every show, the person you laughed at, was me”.

Hogan says he “mentally retired” after co-writing and starring in the most successful independent film in history. (Made for just $8.8m in 1986, Crocodile Dundee earned $US328m worldwide.) “I’ve never worried much about the past or the future,” he says. “I just sort of float along.” He’ll amble out of seclusion every now and then to do a movie, low-key comedies such as the upcoming The Very Excellent Mr Dundee, a tongue-in-cheek rejoinder to continuing Hollywood pitches for another Crocodile Dundee sequel. (Won’t happen. Number 3 “was a mistake”.) He’s also written an autobiography, The Tap-Dancing Knife-Thrower, out in November. The title is a nod to Hogan’s first TV appearance, on the talent show New Faces, a classic bit of mickey-taking that brought him down off the bridge and led to a world-beating partnership with John “Strop” Cornell.

Nearly two decades in Los Angeles have done nothing to sandpaper the rough edges Hogan sold to the world as Made in Australia. He would have you believe he’s always been this indolent, g-droppin’ knockabout, moseying through his films and his days in a haze of unworldly, fish-out-of-water bemusement. And you buy it until he starts talking about his passion for physics and you realise that, even with the whip-smart Cornell in his corner, Hoges didn’t get to where he got by being dim.

It’s a little-known aspect of Hogan lore that the high-school dropout once tested at a genius IQ level, and his all-time idol? Not Benny Hill but Nikola Tesla, the 19th-century physicist and engineer best known for designing the alternating current (AC) electrical system. Hogan’s shy about this, he feels people might poke fun, but he has an idea: it has to do with harnessing the energy of the Earth’s rotation, with copper wire and satellite stations and, well, he’d have to draw diagrams. Tell me more, you say. “Nah, it’s borin’. ” Paul Hogan with a plan to save the planet using free, endlessly renewable energy? You assure him that it’s not.

Hogan’s dialling in from his home in Venice Beach, Los Angeles, where the novelty of lockdown wore off long ago. It’s just him and Chance, the 21-year-old son he shares with his second wife, Crocodile Dundee co-star Linda Kozlowski. The couple split amicably in 2014 with Hogan receiving sole custody. “When somethin’s over it’s over,” he says now. “It’s very true that opposites attract but then one day they’re just opposites.” Physics, isn’t it.

Chance fronts LA punk band Rowdy P. He’s a “stirrer” like his dad, and the reason Hogan is “stuck in LA” when he would, he insists, rather be back in the country of his birth, close to the five children from his 30-year marriage to Noelene Edwards (who remarried in 2000), to his 11 grandkids, and to Cornell, who has Parkinson’s disease and lives in Byron Bay with wife Delvene Delaney. “You’ve got no idea how I wish I was there now,” he says, with a yearning sigh. “But Chance was raised here, he’s got his band and all his buddies here and he’s not quite ready to be left here yet.”

Books of cryptic crosswords are piled high on the living-room coffee table alongside a well-thumbed copy of Conceptual Physics. He’s been watching a lot of television. Making the odd trip to the Venice Beach boardwalk, mask on, to watch the skateboarders and weightlifters, the fun-loving fringe of a divided country that is rapidly losing its appeal. “It’s not pretty,” he says. “You see people sayin’, ‘I won’t wear a mask. I’m a free man.’ No you’re not: you’re an arsehole. And racism? Racism’s for cretins. I’ve seen it all right here, and I say it’s for cretins. How do you go through life judgin’ people on how they look? It’s just absurd. The majority are startin’ to sit up and say this is not right.”

Hogan is anti-racist, pro-same-sex marriage and suspicious of the White House’s relationship with the truth. He also thinks cancel culture’s for cretins. “I am the livin’ picture of political incorrectness,” he says proudly at one point. You trawl back through his oeuvre, viewing it through the prism of 2020, post #MeToo, amid the heightened racial sensitivity that recently saw Nestlé rename its Red Skins and Chicos, and you can see where it might be problematic. So can he. “I know what people might be sensitive about,” he says. “Sexist is the most common [accusation] against me. But I don’t think I ever did anything with any sort of malice. Some people are hypersensitive but it’s understandable I guess. Everything changes as time goes on and we are in the politically correct era.”

Delaney, who played The Paul Hogan Show’s bimbo-in-chief, says she never felt exploited, was always “in on the joke”. She once stood smiling in a lime-green bikini while her body was used as a weather map; these days, aged 68, she cheerfully uploads old episodes to a dedicated YouTube channel. Hogan believes some of today’s comedians are much more offensive. Salting their routines with hostility and sex, spraying profanity like aerosol, “they would have been outrageous back in the ’70s,” he says, “for the language and the inference”.

Dean Murphy, 49, the Melbourne-based director of The Very Excellent Mr Dundee, has worked with Hogan consistently since 2004’s Strange Bed fellows, collaborating on 2009’s Charlie & Boots, TV specials and two national tours, and co-authoring Hogan’s new book. Despite the generation gap, he’s one of his closest friends. “People have never lost their fascination with him,” Murphy says, but he’s often misunderstood. “When we do stuff he always says, ‘No one should pay for this laugh. We can’t have 99 people laughing and one crying in the corner. I don’t want to upset anybody.’ I think people always get that wrong about Paul.”

Murphy acknowledges we’re living in “tricky times”. Strange Bedfellows, a caper comedy about two lifelong friends pretending to be gay for tax reasons, was criticised for its stereotypes but also won a gay film festival prize for promoting tolerance. A scene in Crocodile Dundee that’s drawn fire for being transphobic was praised by The New York Times upon release for being handled with “wonderful deadpan forthrightness and humour”. And, Murphy says, Italians lined up after a tour to tell Hogan how much they loved his moustachioed Hogan Show character Luigi the Unbelievable. “People can look back at the show and say, ‘This was offensive and that was offensive’ but it was 45 years ago,” Murphy says. “Forty-five years from now half of what we’re seeing will be considered offensive, but there’s no one alive that could tell us which half.”

Flash back to the cocky ’70s charmer, Hoges, and you realise: he was just so of his time. That offhand, yobbo blend of colonial naivety and mocking rebellion that spoke to a nation just coming of age. The Hogan who wore footy shorts to meet the Queen. “Evenin’ viewers,” he’d say, full of swagger and winks, bar stool like a throne, hairy legs akimbo. You could see a certain vision of Australia in his lopsided grin: zinc-striped noses and beer-stocked Eskies, a distaste for pretension, an appetite for fun. “The most common thing I hear from people who meet Paul these days is, ‘Geez he reminds me of my dad’, Murphy says.

Australia fell a bit out of love with Hogan in the ’90s. A handful of middling films – Lightning Jack, Almost an Angel, Flipper – landed with a thud. There was the breakdown of his marriage to Noelene; his marriage to Kozlowski further strained relations and his countrymen felt a sense of betrayal when he decamped to the US with his new young bride. There was an eight-year battle with the Australian Taxation Office and rumours Hoges had “gone Hollywood” with a facelift. (He says plastic surgeons have worked on his face, dealing with multiple skin cancers and removing scar tissue caused by a long-ago headbutt from above his left eyebrow, because “it was starting to sag down over me eye”.)

The idea for The Very Excellent Mr Dundee, which mines familiar innocent-abroad territory with genial meta-humour, was born after a spoof Tourism Australia campaign that aired during the 2018 Super Bowl reignited interest in Hogan’s most famous role. Hogan plays a lightly fictionalised version of himself as an ex-movie star, rambling somewhat creakily through a series of mix-ups that leave his reputation in tatters but his manner unperturbed. An early scene has Hogan meeting Hollywood honchos who fail to see the problem in casting Will Smith as Mick Dundee’s son in a Crocodile sequel. Because he’s American? Too old? Can’t act? No, an exasperated Hogan says, pointing out the obvious: it’s because he’s black. “But he is!” the on-screen Hogan later protests to his manager, who spends the film in damage control, fretting about her client’s “legacy”.

Murphy wrangled cameos from Chevy Chase (Hogan’s 1987 Oscars co-host), Olivia Newton-John and John Cleese. “I believe he got into trouble over there about insulting Germany or something?” Hogan says of Cleese, whose Fawlty Towers recently had an episode removed by the BBC. “Inappropriate! The whole point of Basil Fawlty is that he’s totally inappropriate, that’s why it works. Aaargh!” He shakes his head with such vigorous disbelief you can hear it through the phone.

John, 12 years old, is three times as old as his brother. How old will John be when he is twice as old as his brother? If your brain starts to splutter and crash when you read this, you don’t have a brain like Paul Hogan. He tells you a story: In the 1950s, when Australia introduced the concept of standardised IQ tests for schoolchildren, he was studying at Parramatta Marist High School and dutifully sat one. He was a troublemaker, he says, so his teachers were astonished when he scored 140, placing him in the gifted top 2 per cent (most of whom would be able to tell you that John will be 16 when he’s twice as old as his brother).

“I resented it,” Hogan says now. “I didn’t want to be a boffin. I’d been fine getting away with whatever I wanted and then suddenly I was either monumentally lazy or rebellious or something because I should be doing better. So they put me through another test, because of the result. I thought, ‘I’ll just fly through this and not even think about it and that’ll put an end to it’. So I flew through it and my IQ went up 20 points.” Hogan sides with those who dismiss such tests as an unreliable measure of intelligence. “I’m not a rocket scientist, I was just really, really good at IQ tests,” he says. “It’s just a weird part of me brain; most of me brain’s just a boofhead who enjoys making people laugh.”

He left school soon after, at age 15. “I just didn’t want to be at school anymore,” he says. “I wanted to get out into the real world and buy a motorbike.” By the age of 21, living in a Housing Commission cottage in western Sydney’s Chullora, married to Noelene with two children and a third on the way, Hogan was working as a rigger on the bridge. Before that he held a succession of jobs, from construction worker to union-dues collector, in between training to be a lightweight boxer, only tossing it in when legendary Sydney trainer Billy McConnell told him he “lacked mongrel”.

“The funny thing was one of the jobs I had after I finished school was working at Granville Olympic Pool as a lifeguard,” he recalls. “My old school used to come down on Thursdays and do their swimming and one or two of the teachers would point me out to the kids and say, ‘See this guy here, he was really smart. He could have been a physicist’. The kids would look, see a 17-year-old sittin’ on the springboard, chattin’ up girls, divin’ in the water occasionally, and they all thought, ‘Yeah he made the right decision’. So it backfired for the teachers.”

One of the earliest friends he made in TV-land was the performative physicist Professor Julius Sumner Miller. “He used to do a program called Why Is It So?” Hogan recalls. “And I had many debates with him.” You seize the chance to again probe this issue of his nascent invention, the self-generating energy source that sounds like the last thing you’d expect to sprout from the mind that gave us Leo Wanker. “My son Chance pokes at me a bit, but I’ve got two theories on it,” he begins. “Nah, I’ll only bore you if I get sidetracked.”

It’s not evident in Hoges or Mick Dundee, but Hogan reckons there’s a vicious streak in him. “It occasionally flares but mostly it went away,” he says. “I’m not allowed to have a temper anymore; life’s been too good to me.” The early discipline of boxing kept it in check, but it lurks. Things that have made him mad: the painting of Kozlowski by the press as a “scarlet woman” in 1990. It made him want to “cave in heads”. Also: the Australian Taxation Office, whose pursuit of him for $150 million in taxes he allegedly owed made him want to “thump somebody”. Hogan was never charged and has consistently denied any wrongdoing. The matter was settled in 2012 but he remains furious at the way his reputation was muddied. “It still sticks in my craw, very much,” he says. “It was wrong and it still is wrong in so many ways.”

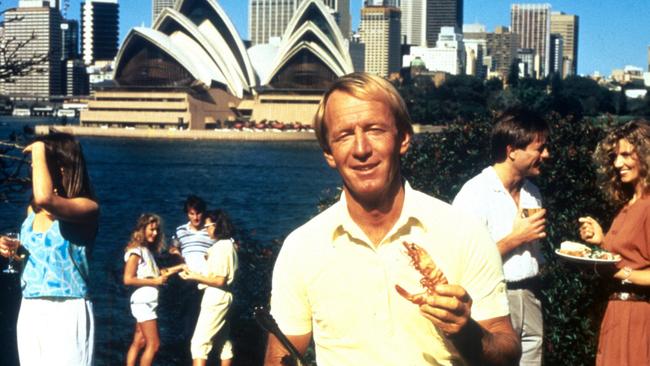

It particularly rankled because Hogan loves his country. He and Cornell refused payment, for example, for the now legendary series of “shrimp on the barbie” ads that sold Australia to the world in the 1980s (although the fact they prepped the US market for Crocodile Dundee was a foreseeable fringe benefit). “We didn’t do it for money, we did it for pride,” Hogan says. “But we also had to convince the boofheads in parliament to go with it: we’re doin’ this because it needs to be done. They didn’t know how to sell Australia; they used to just stick koalas or kangaroos in their ads. What is Australia, a zoo?”

You’re running out of time and Hogan’s going to get away with just a teasing allusion to an invention that he says could save the planet. Think of the future, you beg. Think of the children! “Well… I’m still tryin’ to come to grips with it,” he says. “It’s to do with the fact that the world moves… That’s motion, real motion, and motion is the father of energy.” Go on. “We’re livin’ on a giant generator and we’re still burning fuels. I know what Tesla was gettin’ at. What he didn’t have in his era, though, was the capability of puttin’ a huge copper ring around the world because there were no satellites or anything in his day.” To be fair, you say, we still don’t have the capability of putting a huge copper ring around the world. “It will happen,” he says. “We’ll stop digging stuff out of the ground and setting fire to it.” He spends much of his spare time, he says, sketching out diagrams. “We’ll find a source within this planet we live on; it’s just such a dynamic, living thing. It’s just beyond all of us yet; our brains aren’t developed enough. Hopefully, we’ll do it before it’s too late.”

Hogan’s mum lived to 101: “Never got sick. She died of boredom.” He’s still spry and fit and, Murphy says, “has the curiosity of a 20-year-old”. But 80 can be a reflective age. Does he ever think about his legacy? “Nah, I won’t be here,” Hogan says. He huffs out another laugh, reminded of a funny story from his 2014 Hoges: One Night Only Australian tour. “On the call sheet I was referred to as LFL,” he says. “A couple of journalists interpreted it as Looking For Love, but the real reason was this: I was with my daughter [Loren], we’d bought a television set at a big shopping complex, and this young kid was taking it up to the parking lot for us, bein’ very cool, ‘See you up there’. He was very cool. He got in the elevator and the doors closed and we heard this roar coming down the elevator shaft as he went up: ‘Paul Hogan! Living F..kin’ Legend!’ So I become LFL on the tour. It was nice. He was just a young kid; he wasn’t even born when Crocodile Dundee came out.”

Hogan chuckles softly, still tickled by the memory. “But you can’t print that,” he says. Why ever not? You’re puzzled. “Well,” says the eternal rogue, the bloke who upended decorum, middle- fingered the establishment, “as long as you don’t use the swear word.” He pauses. “Maybe you could just say ‘frickin’.”

The Very Excellent Mr Dundee streams on Amazon Prime from July 17.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout