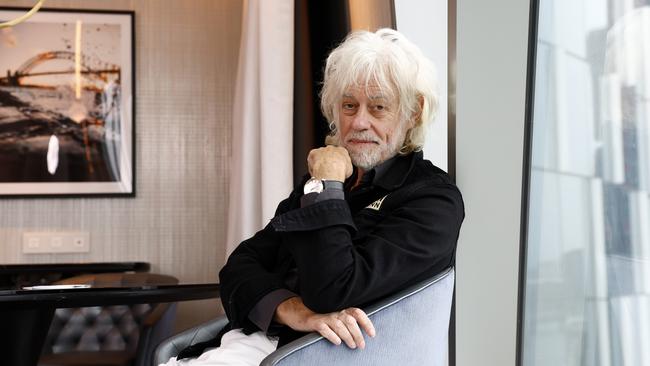

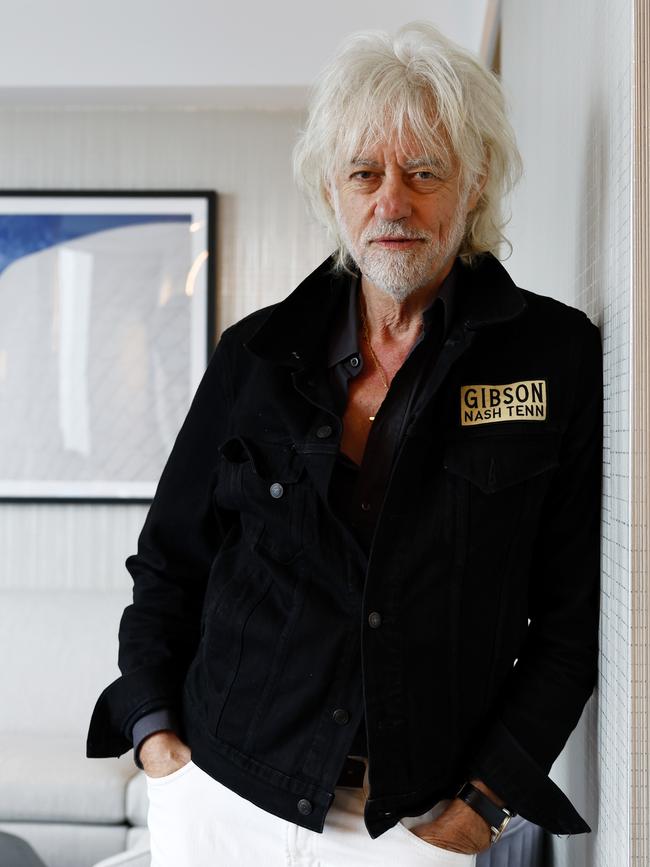

Bob Geldof on money, smuggling painkillers and the declining value of rock ‘n’ roll

At 73, the frontman of Irish rock band The Boomtown Rats – and organiser of iconic benefit concerts Live Aid and Live 8 – reflects on money, his alter ego and smuggling painkillers.

Ahead of an Australian tour, the frontman of Irish rock band The Boomtown Rats and organiser of the iconic benefit concerts Live Aid (1985) and Live 8 (2005) reflects on money, his alter ego ‘Bobby Boomtown’, smuggling painkillers and the declining value of rock ‘n’ roll today.

Review: Hello, Bob, thanks for making time. You’re in Sydney on a brief promotional trip, and in the midst of press engagements. How’s it going?

Bob Geldof: It’s a f..king pain. For 50 years, I’ve been doing this bollocks.

Is there anything I can do to make it less painful for you?

Go away! (laughs) Come down to the hotel, buy me a pint. That’ll do it.

I would if I could, mate, but I’m in Brisbane. We’re talking ahead of your Australian tour, where you’ll be performing songs and stories from your life. What attracted you to that format?

It was suggested to me, rather than it was my idea, which is always a good thing; you noodle it around your head, because you haven’t done it before. In the middle of all the stuff that’s happening (in 2025), which is the Live Aid 40th anniversary; there’s a lot of hoopla around that, and it gets a bit weird, to be honest. So to break out, and to be by yourself, will be a break – that’s first. It takes me out of my comfort zone, which I like; that’s two. It’s a challenge; I may as well tell the stories to an audience as (opposed) to just mates hanging around. I’ll do a couple of tunes: the more famous ones, but also other ones that maybe explain more what was going on at the time. I’m actually looking forward to it, simply because it’s very different for me.

Have you always enjoyed touring?

At the beginning it got so wearisome, just endlessly going around; even though you’re a kid and you have energy, it was exhausting. But at the same time, it was the singular point of the whole thing. So you’d travel through the vast wastelands of the United States to come to some small town in late October, and the bus would park under flood lights in a carpark, and you’d wait there, your clothes drying from the night before. You’d be sitting there with a cup of coffee until the venue opened, you’d go into a cold dressing room and hang around there. Then you’d go on stage and you’d become ‘other’ – and then you’d come off stage again, and your clothes would be doubly wet. You’d get on a bus and head off into the night. So, no – not great.

But the performance itself was always enough of a lift to make it worthwhile?

It was always cathartic, but it was a sort of predetermined activity. You had to do it to sell records, to get to where you wanted to be, so people would want to buy your records. Now, it’s a different sense. Now, I could be talking to you like this, and then they’d say, ‘You’re on’, and I’ll go on, and I will absolutely change into something other. I’m sure you’ve talked to a lot of performers, and they’ve said the same. I know that some people get great nerves; I don’t. The minute I hear the noise of that band (the Boomtown Rats, who still play occasionally), I find it thrilling, even though I’d have done it the last five nights in a row.

Is there a transformational aspect to it?

I don’t want to get all mystic on you, but there’s a part of my person that comes out, and I call him ‘Bobby Boomtown’. He just goes nuts on the stage; he can say and do whatever he likes, and you’re in a different space. You’re certainly aware of the audience, you’re aware of mistakes and things around you, but you’re just moving free. Everything’s free. Your mind roams free. You’re very familiar with the songs, so if you’re coming up to I Don’t Like Mondays for the 9684th time that year, you’re not in a state of, ‘Oh God, here we go again’ – because as soon as the opening bars hit you, you go into a place that that song suggests. You’re not back in the moment when you wrote it, where there was a thought process that was unpeeling from your subconscious. You’re into whatever that song suggests. It’s almost part of the routine: you’re there and you’re in that moment. It is extremely cathartic.

What happens when you come off stage after a good gig?

It’s that moment afterwards that I really love, when you’re with the band and the crew have packed up, and they come into the room. People say you’re on a high; you possibly are. I’m not aware of that. I just feel a deep sense of satisfaction. Obviously your adrenaline is very high. And also, of course, conversely, if the gig has been shit, I really want to kill myself. I really can’t let go of this beating yourself up (mentality). I’ll get back to the hotel and, trying to sleep, I’ll be punching myself, almost, with rage … that I knew it could be better. Yes, the crowd have probably gone nuts – but ‘If only they’d seen us when we were X, as opposed to when we were …’, you know? So it is very extreme.

Do you have a warm-up routine?

I’ll go for a nap in the afternoon for about an hour. When I wake up, I have to have strong black tea, and then I have to take two Aspro Clear, those effervescent tablets. It’s a direct injection; a mainline into your system because it’s effervescent, soluble aspirin, so it just goes in. If you’re a bit sore and stiff from the night before, it loosens you up, and off you go. Problem is, they banned the f..king thing in England for some stupid reason. So when we come to Australia, we stack up with Aspro Clears and sneak them back into the UK – or else simply the gig can’t go on. It’s my routine. (laughs) It’s odd; I’ve read some of your (Confessional Q+As) to clue in on what this (interview) was about, and I’ve seen the performers who clasp hands and all this bollocks. No, that’s not for me. I like it if we’re joking around beforehand, because then you go on with that. But it’s not necessary; I just go from zero to 10.

It sounds like touring really suits your personality, and that you thrive in that environment.

Up until recently, I would say yes, because it’s also running away. The Scientologists call it ‘going clear’ – it’s a good expression. ‘Oh, I have to go. Sorry, it’s my job. I won’t be home for X.’ Then there’s the moaning that you’re going away: ‘But I’ve got to earn money, that’s my job, I’ve got to play the music …’ That was always a good ‘get out’ clause – and of course, a week or 10 days into (the tour), you want to go home. It’s very contradictory, and it’s not the best thing for maintaining a domestic life. You miss the kids, you miss the missus, you miss being home, you miss your mates, and that becomes more and more acute. So in every which way, rock ‘n’ roll is very much a young man or woman’s game. It is exhausting when you’re going: if you hit those magic chords that you’ve been looking for all your life, and they’re going to make you a millionaire, you go. And the record companies make sure you go.

Is it the same now with streaming? Probably different, but probably not. But it is endless, and you’re the guy who writes the songs; you’re the singer, therefore you’re the guy who has to do the interviews, because it gives the journalist something to talk to you about. So all of that happens, and it’s non-stop, because the economics for touring are so disastrous if you’re not in the top 0.0001 per cent. You’ve got to keep going. These days, I can do it at the pace I want to do it. I can play in the places I want to, and it’s less driven, because that notion of ‘career’ either has worked or it hasn’t by this stage of the game.

Was running away part of the attraction for you, early on with the Boomtown Rats?

Yes, it was. My mother died when I was very young; seven, say. My dad’s job was selling towels and stuff in rural Ireland, so he’d leave on Monday and come back on Friday. He didn’t have a choice; there was no economy, that was the only job he could get. My sisters and I were left to our own devices, and it wasn’t fun – not that I was really aware of that at the time. It just was what it was. But part of the result of that was that I just didn’t bother doing anything at school. I just listened to the radio and read books and stuff. Ireland was not going anywhere (economically) – and then, when the band sort of happened, it was the instrument that gave us escape velocity. I provided the fuel: it turned out I could write songs. I didn’t know I could. The bass player (Pete Briquette) suggested we write our own stuff, so I said, ‘That’s a good idea’, and suddenly I was turning out songs that turned out to be very big hits.

When it became clear we could get out, and take a risk of moving to the UK and throwing all our hats in the ring, all of us (did), without demurral; I can’t remember a single argument about leaving Ireland. The intensity of the band at that time matched the intensity of the period: England in 1976 had an inflationary rate of 27 per cent. Crazy. So there was a lot of anger, a lot of confusion, a lot of rage – but we came fully prepped for that. And so right time, right place, right amount of talent – but also the right mentality. I wanted the world, darling, and that’s what drove us, those two dynamics: no family, no future in that country. We’re stuck; let’s get the f..k out of Dodge. And we did.

I get the feeling you’re using me as a sounding board for your tour; these stories are fantastic. Do you have another call after this?

No, I’m done after this thing. F..k – I am going to have a very large vodka martini, Andrew, after this. I deserve it because of you.

Fair enough. Thinking back, what did you want to get out of a life in rock ’n’ roll?

Three things: I wanted to get rich, I wanted to get famous, and I wanted to get laid. I came out of Catholic Ireland; trying to get shagged in the ’60s and ’70s? You can f..k off. It’s not going to happen, period. So that was out. I wanted to get rich because I wanted to try it at least; just let me try it once. So then I got there, and I am here to tell you that being rich, Andrew, is a lot better than being poor. Poor is shit all the time. It is never good; it is never fun. It’s horrible. And as for the fame? I wanted that because I wanted to use the platform it gave me to talk about the things that bothered me. So I’ve done all three of them.

Do you have a philosophy on money?

I definitely like having it – but in my mind, I don’t have any. And that you carry around with you since being very poor. I don’t want that to sound Dickensian; we were worse than that. We were the desperate middle class, my father still clinging by his cracking fingernails to the precipice of respectability, which was sad. But as a result, he sent me and my sisters to very good schools; he spent every penny he had on that. I just had no interest in that – which now I feel sad for him, that I was such a pain and we didn’t get on. Subsequently we became good mates when everything resolved into adulthood. But it definitely stays with me: I have to earn money, constantly. At this point in my life, I don’t need to; even saying that to you, a part of me is going, ‘Oh yeah?’ And the other part – somewhere located in my stomach, believe me – is going, ‘That’s amazing’.

You’re in the unusual position of having been a conduit for people donating many millions of dollars to poverty and famine relief. Has that changed your view on money and its value in society?

God, that’s a good question. Very interesting. (pause) No.

No, because I wouldn’t have answered that question when I was young in the way I did, had I not understood that to be the case. Money does give you a freedom to operate in this world; you just have to look at the force of the American election to understand that a plutocracy has taken over America. So government by wealth is illegitimate as much as autocracy government by military might in, say, thuggish Russia is illegitimate. Money is deeply perverse in that it can do fantastic things. Fame, likewise, is a currency. It depends on how you want to spend it. If you’re wise, you can invest it wisely if you’re into that, or you can save it; you’re careful with this brute force. The economy applies to everything in our world.

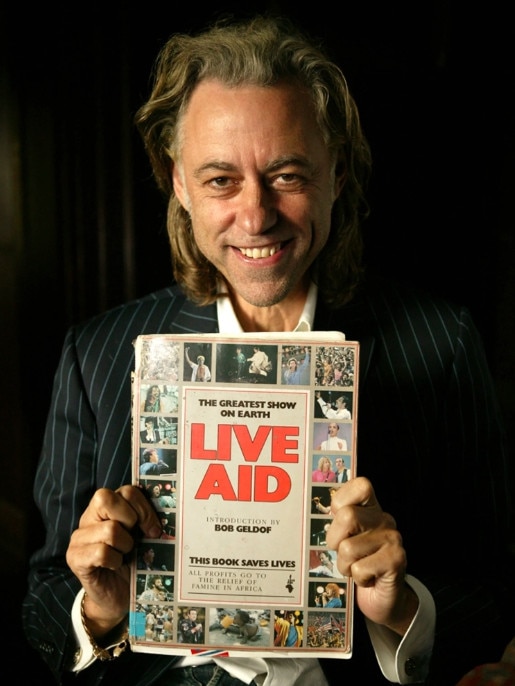

What are your views on where anti-poverty campaigns are today, compared to when you were putting together Live Aid in 1985?

It’s not a good thing to be involved in at the moment; they struggle. And I swerved way off your point in the last question; I’ll come back to it, because it’s pertinent to this question as well.

Every day, I wake up to 10 or more emails about the latest horror in the areas of Africa we’re working (in). In Sudan, which is barely acknowledged at all, the UN estimates 2.9 million people will die this year of war and starvation, which dwarfs the other horrors (in, for example, Ukraine and Palestine). It goes to my argument about how do you use any currency, whether that’s fame, cash, power or any other thing that could be transmuted into another.

You don’t actually die of hunger; you die of want. Want is economic. If there’s hunger in Australia, the government buys food and you take it from the supermarket. They’re poor (in Sudan); they have an absolute of nothing. They have no currency, so they die because there’s no food, and there’s no mechanism for getting it. It’s an economic problem, so to deal with the issue, you must engage with the agents of change that deal with the economy. And those agents of change – for good or ill – are politicians.

So this is all ultimately political. The anti-poverty campaigners, yes, they try and tap the public’s conscience, but mostly where you get any sort of juice at all is by creating a lobby for government. There are two areas the government will pay attention to: one is a lot of money, or secondly, a lot of people supporting you; then they can’t afford not to see you.

What do you say to people who feel powerless on this matter, as individuals?

We do have agency on this issue: it is an absolute fact that if you engage by putting a buck into a charity box, or flashing your card across something, or making (a donation) with your PIN – that night, it is almost guaranteed that that panicked woman and her exhausted children will go to bed warmer, safer, better fed. So you do have agency to change things even slightly; even if it’s for one night. And that’s where I’m at, still.

Do you consider yourself an optimist?

Not at all. I mean, that’s the last thing people would say about me. I’ve limited individual agency to one-on-one; the individual action has got consequences that can be positive. But against the superstructures of power, you’ve probably never been more impotent. Your constant swirl of prime ministers (in Australia) is an example of that. The constant dissatisfaction that your leaders are not delivering what it is you require – but I’m not sure that we even understand what it is we require. We are in a seriously historic period of change; a historic cusp that, if we survive, will be talked about in 300 years. It’s brought about by this immense technology that has never before been conceived of. In the past 20 years, the economy has moved to the pace of the internet, which is far faster than what we can comprehend. And so the market behaves in this odd way; that’s the economy. We behave in increasingly odd ways; that’s social media.

Is there still a role for music in social movements today?

Rock ‘n’ roll as an instrument of change is over, because it’s free. It’s no longer art. Art has value; if it’s got value, you pay for it. If it doesn’t have value, it’s not considered – it’s simply a background to your life. There are great writers, there are fabulous bands — but they are not the spine of the culture any longer.

The period from 1956 to 2006? Rock ’n’ roll turned out to be a 50-year pop: the significance of Elvis, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Sex Pistols; whoever came afterwards, the NWAs and hip-hop guys – that’s gone. I mean, I learned everything in my life – sociology, economy, politics, philosophically, theologically – it all came through rock ’n’ roll. That simply isn’t true anymore. It comes through the echo chamber of your own prejudices, which is your social media feeds. We’ve changed completely, and we’re floundering in that change.

Given that it gave you so much, do you mourn the loss of rock ’n’ roll as a cultural force?

I miss it as the rhetoric of change, and I miss it as being the platform of change itself, which is what Live Aid and Live 8 actually were. We were able to use it, and the greatest exponents of that great art form – rock ’n’ roll – from the very beginning: from BB King through James Brown, right up to Beyonce (with Destiny’s Child) and beyond, all of those played (at those two events).

Retrospectively, when it comes down to it, look at the roll call: Roger (Daltrey) and Pete (Townshend, of The Who) couldn’t stand each other at the time, yet they put down the battle axes. I asked them. Led Zeppelin reformed; I didn’t ask them to. The Beach Boys reformed; I didn’t ask them to. Pink Floyd cannot abide each other, but I asked Roger (Waters) and Dave (Gilmour), and they put down the f..king weapons and played. So something happened. I spurred them on.

But was there some instinct that this was the last hurrah, goodbye and thank you? I don’t know. Those bands still exist, but does Paul McCartney have any significance whatsoever (today)? No – he’s just a man who wrote some of the greatest songs ever, and whose songs will be sung (forever). Paul Simon has left the stage – one of the masters of the craft. Do we miss him? No, we don’t miss him live; his songs will go on.

But will they have the resonances? Will they have the driving urgency of The Who? With the code of rock ’n’ roll, you didn’t have to understand the words; it was so primal that the noise was an articulated howl of ‘no’. Just ‘no’ – and yet, endless subtleties within that. That still exists as song. But can it move the cultural, political needle? No.

It was our social media – and now social media is something else, and that’s what drives everything. (pause) I’m bored. I’m gonna go.

Bob Geldof’s nine-date Australian tour, titled Songs and Stories From an Extraordinary Life, will begin in Sydney on March 15 and end in Perth on April 5.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout