Tommy Emmanuel on persistence, grit, addiction and surrender

Guitarist Tommy Emmanuel has spent most of his life as a fixture of Australian culture. Now he’s ready to open up about his decades-long cocaine addiction and the terrible family secret that drove it.

He holds his hands in front of him, eight fingers and two thumbs facing skyward, admiring the eminently dexterous tools of his trade as one of the world’s most admired experts in his field.

If you know anything at all about Tommy Emmanuel, it’s that he knows the guitar like the rest of us know breathing. It’s those two thumbs to which he is drawing attention, on this video call from his Nashville home in early February, as there’s something a little peculiar about the way those digits have developed during his life. It’s not a stretch to wonder whether they contain the source of his singular power.

His right thumb – on which he usually wears a pick, owing to his distinctive fingerpicking style – is held straight like a finger; his left thumb is much more bent and supple, owing to the vast array of unusual positions he has forced its muscles to occupy, over and over again, in search of greatness.

“You can see that I have to make my hands be a contortionist when I’m playing that,” he tells Review, letting out a brief giggle at his unusual word choice. “But it’s all about getting the melody and the chords and everything to all just be right.”

Put another way, it’s more akin to mind over matter. “I basically make my hands do what I need them to do,” he says, “And I practise it and push it until it becomes natural.”

This thumb-related pause arrives midway through a demonstration he has been giving with his trademark easygoing glee. Asked in advance of this interview whether he would be up for sharing some of his skills on camera, the answer was an easy yes, for if there’s one thing Emmanuel will never miss, it’s the opportunity to entertain.

When the call begins, a favourite acoustic guitar is cradled in his lap as he smiles broadly, short-cropped white hair spiking atop his head, and wearing black-framed glasses in front of eyes that sparkle with a sense of avuncular mischief. He also sports a black long-sleeve shirt bearing the name of the Melbourne-based manufacturer Maton, whose musical instruments he has been playing since 1960.

Sure enough, it doesn’t take long before the wooden weapon perched on his right knee springs to life: within minutes of our greeting, he is working the fretboard with the studious-yet-laid-back expertise of one who long ago found his calling in 12 musical notes, a galaxy of chords and the endless permutations of beautiful sound to be found in plucking six steel strings.

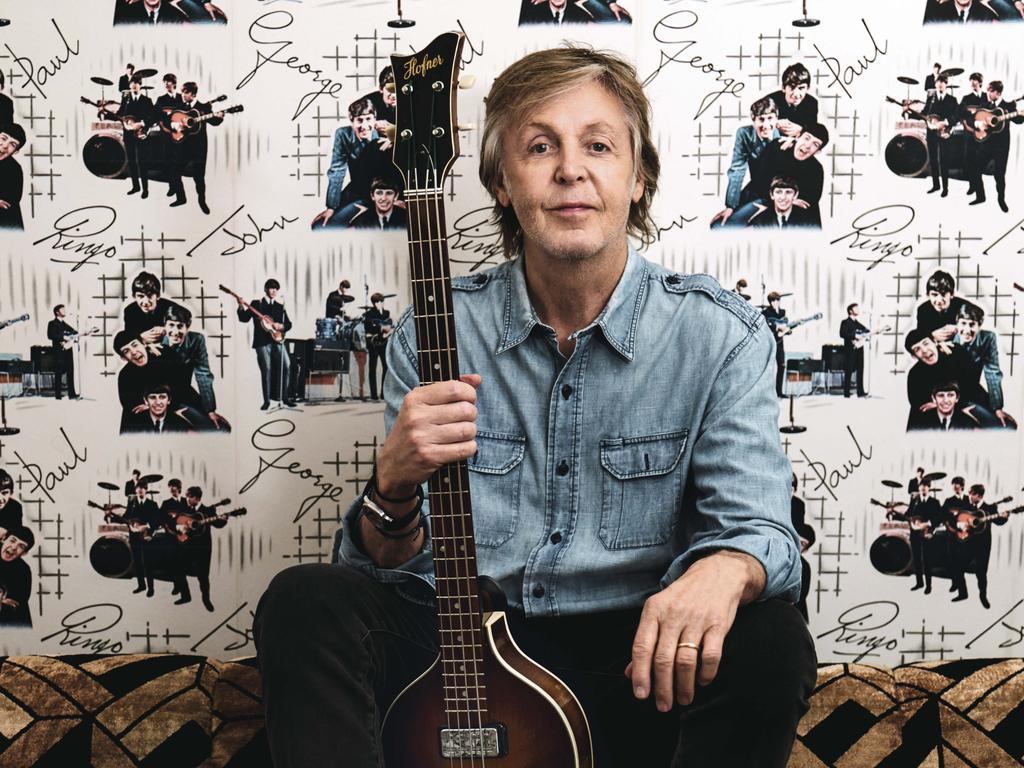

Here he is, demonstrating the freakish talent for musical arrangement and execution that saw him adapt and transpose several hit singles by The Beatles on to a single instrument, played by a single man, whose hands are able to follow the melody, rhythm guitar, bassline and keyboard chords simultaneously.

“When I was trying to work out how to play Day Tripper, for instance, I knew what I wanted to do – I just didn’t know how to do it,” he says. “I had to try to figure it out. It’s so hard when you’re starting from scratch; when I look at it now, it all makes sense, and my hands can do it because I’ve been doing it a long time.”

On stage, Emmanuel whips these Beatles classics into an intricate medley that is nothing less than dazzling. To watch him casually unfurl these masterpieces one-on-one, intimately, is a rare gift akin to watching one of the world’s great sleight-of-hand magicians from up close. (Luckily for you, dear reader, we recorded the call; you can watch a highlights package of this man at work in the embedded video below.)

Yet as the US performance duo Penn & Teller are fond of saying: sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect.

The trick of Emmanuel’s artistry, as it were, is the sheer depth of study and devotion to the craft that is evident with every move he makes. Nobody gets as good as he is without investing their life’s work in such mastery.

Inscribed midway down the neck of Emmanuel’s guitar, at the 12th fret, are the initials “CGP”. They form a central pillar in the story of his life in music, as the three letters signify “Certified Guitar Player”, an honorary title the great American country guitarist Chet Atkins bestowed on Emmanuel in 1999; one of only five instrumentalists to which Atkins gave that particular nod, before his death in 2001, aged 77.

Among guitarists, there are no more meaningful letters in the English language than those three – yet to those listeners who admire the instrument and Emmanuel’s command of it at a remove, there’s another CGP that comes to mind: concentration, grit, persistence.

Asked what those words mean to him in the context of his work, he replies, “That’s three qualities that you need to have if you want to be any good at anything. I can remember my sister, God rest her soul, saying to me, ‘You better grow the hide of a rhinoceros if you’re going to travel around the world, and if you’re going to take your music to new audiences’ – and she was right.”

With the hard-earned confidence of one who knows, he says, “Persistence is something that you’re going to have to dig deep for. You can’t quit on this; if you quit on it, you fail. Only people who quit fail.”

This conversation with Emmanuel was set up for a couple of reasons: in April, he will release Accomplice Two, a second album of duets and his 26th album overall. Soon thereafter, he will tour Australia for the first time since 2019, on a 16-date theatre run that will include a debut headline appearance at Blues on Broadbeach, a free festival held on the Gold Coast.

Yet despite these ostensible promotional concerns, the usual obligations are nowhere to be found in our 90 minutes together, wherein he presents as an open book willing to discuss anything and everything.

This openness extends even to the painful reality of his cocaine and alcohol addictions, which had been well hidden from the millions of Australians who have come to know his name and his musicianship, perhaps first as an electric guitarist in the 1970s with the likes of Dragon, John Farnham and Doug Parkinson, then later striking out on his own as a solo acoustic player from 1987 onwards.

This is a man who has spent most of his life as a fixture of Australian culture, forever somewhere on the spectrum between mainstream commercial success and cult idol. He appeared regularly on national variety TV shows in the 1990s, and has played no bigger live gig than at the Sydney Olympic Games closing ceremony with his older brother Phil in 2000, before a massive global audience.

Unbeknown to most, he was burning the candle at both ends.

“I think a lot of people knew about it, but they didn’t say anything,” says Emmanuel of his cocaine addiction. “It came in and out of my life. Some people wear it like a badge of honour. I don’t. It just happened, and that’s the way I was. It was exciting, and it made me do crazy things; playing for hours and hours and hours and hours. That’s how it started out: ‘This is what they do in America, it’s really cool’, you know – but there’s nothing cool about that stuff.”

In 2019, Australian journalist and filmmaker Jeremy Dylan issued Tommy Emmanuel: The Endless Road, an absorbing and artfully told 80-minute documentary about his life and times.

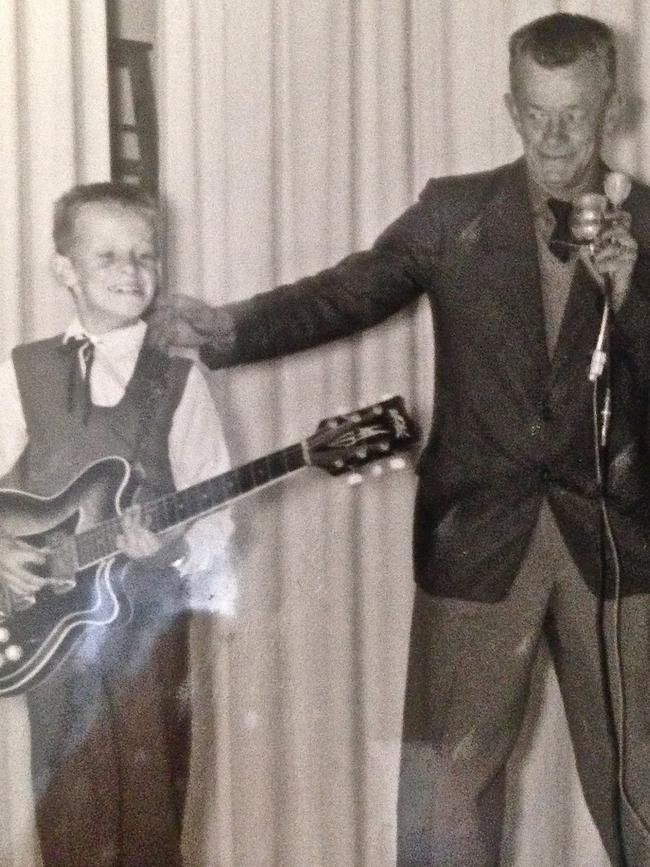

In it, we learn that the Muswellbrook-born musician has spent almost all of his time on this planet with his fingers and thumbs gripping various guitar necks, having begun playing by ear at the age of four, then becoming a quick study on rhythm alongside Phil, who played lead.

Together, they formed a family band with their siblings Chris (drums) and Virginia (lap steel), while father Hugh ruled his brood with an overly forceful attitude, as the family travelled from town to town around Australia, eking out a living.

“You can always be replaced,” Hugh would tell his children, particularly if they’d made any obvious mistakes while performing. Ever the hard taskmaster, those harsh words – the very opposite of unconditional love – shook Tommy to his core, destabilising his sense of self, warping his worldview, and pushing him toward an unquenchable desire to overachieve.

Hugh died suddenly from a heart attack in 1966, when Tommy was 10, but those words would echo through much of the guitarist’s life, causing untold pain and sending him down a path of substance abuse that would take decades to wrestle under control.

His appetite for self-destruction was hastened in his late 20s, when Virginia confessed a terrible family secret: their father had serially sexually abused her, and she had fallen pregnant as a result, giving birth to a child that was stillborn.

“That information changed my life forever, because my father was my hero,” says Emmanuel in the film. “He was built up so much to me when I was young; I idolised him so much. When my sister told me that he’d abused her for years, I didn’t know how to take that, but it hurt me so deeply … It took me half my life to deal with that information.”

Asked about his impressions of the film, whose production began after Dylan wrote a magazine story about the guitarist for Tamworth Country Music Capital News in 2015, Emmanuel tells Review: “It’s hard to be objective, being the subject of a film, but the thing that I liked was the fact that everything was just open and honest. It was warts and all, and that’s the way life is.”

Both Virginia and Phil were interviewed for the film, although both siblings died in 2018, prior to its completion, aged 69 and 65, respectively. For Tommy, were there any hesitations in sharing that tough stuff – their father’s sexual abuse, and his frank experiences with addiction – on camera, to later become public knowledge?

“No, I have to talk about it; well, I had to at the time, because I was fairly new to ‘the program’, and I had to learn how to live again,” he replies, referring to the 12-step program for peer-led mutual aid run by Alcoholics Anonymous, a rare context in which quitting is seen as a resounding success.

“I also had to get therapy and face all my issues that have driven me all my life; all of those are about what’s in the film,” he says. “It’s been such a beautiful time to find the right help, the right therapist, and to bring all those things out that used to rise up in me, and I would push back down with drugs or alcohol. I would numb all that pain away. That’s what we do; that’s why we like alcohol, because it takes away all that stuff that wants to rise up.”

Now 67, Emmanuel has been sober for three years. “I had lots of goes at it,” he says. “I was so set in my ways, so used to living that way, and so used to being the boss: ‘I’m in charge of everything, and this is what we do.’ Once I got broken enough, I had no choice but to surrender and say, ‘I can’t do this anymore. Someone else is going to have to run the show’.

“So I’m not in charge anymore,” he says, smiling with relief. “It’s a power greater than me that’s driving me.” (Step three of 12: “(We) made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood him.”)

Emmanuel’s cocaine use escalated in the 1980s, as he became an in-demand session player, songwriter and touring musician. The cultural mores of the music industry at that time meant that the white powder was ever-present, and not viewed much differently from someone using strong espresso as a pick-me-up. Looking back, what was driving that usage for him?

“Well, I was crazy about it, like most people were,” he replies. “When I first tried it, it reprogrammed my head straight away: ‘Cocaine equals great times, excitement and creativity’. Your brain gets rebooted by that drug, and what happens is, when you want to have a great time and forget all your troubles, your brain tells you that that’s what you want.

“That has to be reprogrammed, as well,” he says. “I think of the times that I had cocaine every day; it was a crazy life. It’s a deep, dark, big beast, and it will destroy you. I’m so lucky that I survived. I’m so grateful to be well today, and to be present in my own life.”

To date, The Endless Road has only been shown at film festivals, where it has been warmly received. Music licensing issues stemming from the pandemic have set back plans for a wider release, but the director and his producer, Jaime Lewis, are hopeful the documentary – which is essential viewing for Emmanuel fans, and for anyone curious enough to have read this far – will become widely available within 18 months.

“Tommy is as good as he’s ever been, at this point in his career, and you really can’t say that about a lot of musicians in their 60s,” says director Jeremy Dylan, who is also a concert promoter, and whose late father Rob Potts was Emmanuel’s booking agent from 2003 to 2017.

“The unique thing about Tommy is that he’s not just in his 60s – he’s been making records since the 60s. He’s in his sixth decade of being a professional musician because he started so long ago.”

“I think we’ve reached the point now where there’s this cross-generational understanding of him in Australia,” says Dylan, who is 32. “And it’s not by him doing anything different than just by being who he is for so long, and never having a fallow period; never having a dip, crazily enough, despite what had been going on in his personal life; never having a moment where his skill or his performances or his music has any dip in quality. Just by sustaining that for so long, I think the world at large has started to catch up with how incredible he is.”

Confession time: heading into this story, I had great admiration for Emmanuel’s undeniable musical talents for playing and arranging, but wouldn’t have thought to include him on a shortlist of six-string slingers who oozed cool.

Never one to adopt the leather-panted, open-shirted, long-haired look of archetypal guitar heroes such as Jimmy Page or Slash, he has instead taken a more bookish, business-formal approach to his public image, especially since the turn of the century: less Paradise City, more Big Dad Energy, shall we say.

With hindsight, I was wrong. Deeply wrong. When I raise this topic with Jeremy Dylan – whose estimation and admiration for his documentary subject has only grown in the years since the film was completed – he replies, “When you see him up there, and see what he can do with a guitar, and the physicality of all that, it’s cool as f..k. It’s Jimi Hendrix, Paul Simon, Eddie Van Halen and Chet Atkins, all the different types of cool, rolled into one – except disaffected cool.”

“Tommy’s never had any patience for that, or any interest in being the type of cool where you pretend not to care,” says Dylan. “Because if there’s anything that Tommy Emmanuel does, it’s care. He cares about the audience, he cares about the music, and he doesn’t care who knows it. It’s a braver posture to have, because it’s more vulnerable: if you put yourself out there as ‘I care deeply’, you have to live up to that.”

Which is precisely what Emmanuel will set out to do in May, when he leaves Nashville – his home since 2003 – and returns to his homeland for a series of concerts hot on the heels of his 26th album release, still bursting with creativity, curiosity and a hunger for self-improvement more than six decades into his remarkable career.

One day at a time: that’s the mantra of recovery programs. Alcoholics and addicts are never really cured, and the desire never fully disappears. You can’t change the past, but you can control your future. Those obsessions can be lifted, those habits can be rewired, and you can achieve freedom through surrender, and with the love and support of friends, family, and admirers the world over. All it takes is concentration, grit and persistence.

Accomplice Two will be released on April 28 via CGP Sounds. Tommy Emmanuel’s Australian tour begins in Canberra (May 7) and ends in Melbourne (May 28), including a headline appearance at Gold Coast’s Blues On Broadbeach festival (May 19).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout