‘People see the irony’: How a Monty Python song became a funeral classic

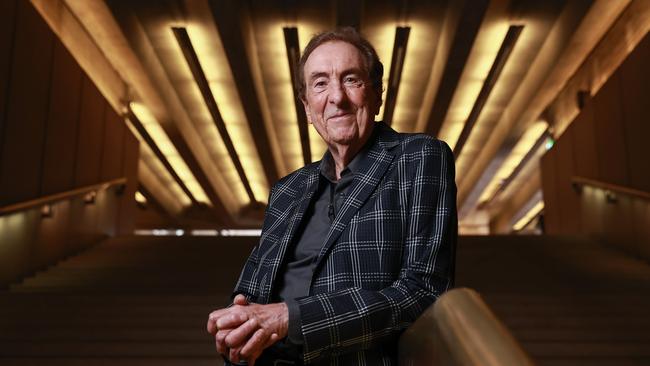

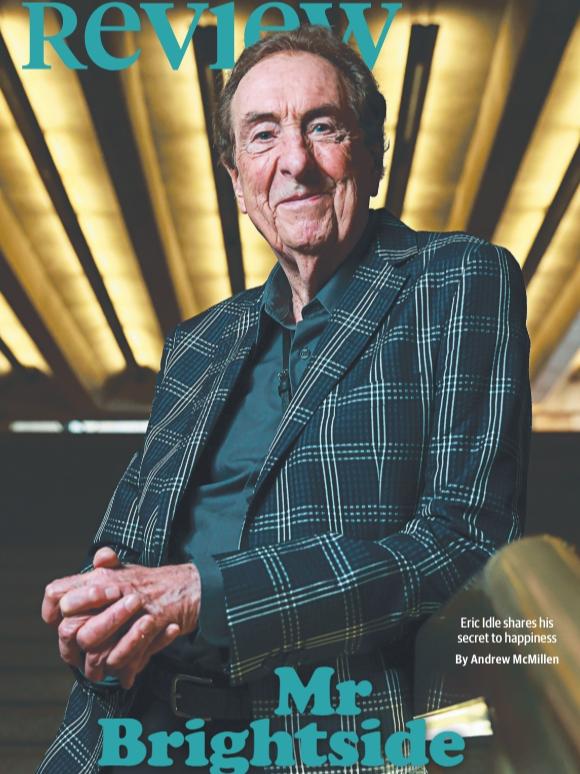

Ahead of an Australian tour, Monty Python co-founding writer, performer and musician Eric Idle reflects on his hit transforming funerals into more upbeat affairs.

Ahead of an Australian tour, the Monty Python co-founding writer, performer and musician reflects on comedy, genius, libido and facing life’s final curtain with a bow.

Review: Eric, this is an extended version of our Confessional interview format. When did you last confess, in a religious sense?

Eric Idle: Oh, I’ve never confessed. I’ve never been a Catholic, so I don’t believe in all that stuff. Mind you, you could argue that therapy is a form of confession. I had about 30 years of that, so I’ve done a lot of it (laughs) but you don’t have to light candles, that’s the great advantage.

We’re talking ahead of your Australian tour later this year. When did you last visit?

Two years ago, I was in Sydney. I played the State Theatre with Shaun Micallef, and we had a fabulous evening.

Shaun is one of Australia’s great comic performers and writers. What were your impressions of him?

We worked together, because I like to write my shows a long time (in advance) and rewrite them. He’s like me – a bit of a writer and obsessional – so we bounced it back and forth. We never even met until about 24 hours before we went on stage, but we’d been working together on the show. We made a different kind of interview show; we ended up having a fight on stage, which I really liked (laughs). We did things that were completely unexpected: he did sketches with me, and we even did a dance routine at one point. That was really great fun.

I believe your work has been a big influence on Shaun’s style of writing and performance. How do you manage situations where you’re working with a younger performer whose comedy world view you helped to shape?

I think you pass it on. I mean, I got my inspiration from (1960s British comedy revue) Beyond The Fringe: Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller and Alan Bennett. They changed my life. It’s the same with music: you like somebody, you copy their music, and then you discover your own little area where you’re going to go into. The thing I like about comedians is they tend to be supportive of each other, because they know how difficult it is to make people laugh – whereas (in) rock ’n’ roll people are very competitive. They’re more like birds; they flutter at each other.

How has your relationship with live performance changed across the years?

What I try and do is keep my stamina going. So what I’m doing this time is I’m bringing a virtual band, and they’ll be on screen with me. They’re mainly the Monkees (tribute) band. They’re really good, and I’m doing it like a one-man musical. It’s going to be fun with new clips, and different things that people haven’t seen – like (Rutland) Weekend Television – [that]are less viewed, but still, I think, very funny.

Do you get nervous moments before walking out in front of a crowd?

You should be a little bit nervous; you’ve got to be alert, and you want to go out there. But I don’t mind it usually. I find myself enjoying it. If you prepare yourself properly, there’s nothing to be nervous about, really – just whether they will like it or not. The audience will tell you what’s funny. You don’t tell the audience what’s funny; you suggest something to the audience, and they either affirm or deny that it’s funny. I think it’s very interesting that they are the ones who decide what’s funny, not you.

As the writer and performer, you can bring a bag of things that you think are funny, but it’s not until you open the bag in front of people that you truly know?

It’s like algebra: you have to phrase it properly so that they get it. Because what happens is they laugh faster than they think. They find themselves to be laughing all together, and it’s an extraordinary thing when they’re all getting it. But if you’ve misphrased it, or if you haven’t got the equation right, and they don’t understand it, then they don’t laugh. The speed of thought is very interesting to me. I’ve spent 60 years doing it, so it’s still fascinating to me, what makes people laugh and, and what doesn’t.

What was the first money you ever made?

Working at the post office at the age of 13 and 14, doing the Christmas post. They’d take on kids like me from school, and we would have to get up at four in the morning and start delivering all these Christmas cards and packages all round Studley and Warwickshire. It was pretty good money, though.

I did that kind of Christmas mail-sorting job as a teenager, too, and I found it deathly dull.

Oh yeah. Except on Christmas Eve, when everybody gave you a drink, so you’re completely pissed as a fart by the time you’ve finished your round (laughs).

What, as a 13-year-old?

Yeah! Hello – we were at boarding school. We made our own drink (laughs).

Since then, have you developed a philosophy on money?

Yes, I chose to ignore it. When we were filming (Terry) Gilliam’s (1988 film The Adventures of Baron) Munchausen, and everything was in lira, and coffee cost you 20 million lira or something, I lost all sense of what money is. And the other thing about show business is, sometimes when you’re working very hard, and (being) very funny, you don’t get any money. But a few years later, it all comes in again, because of what you did (back) then. So there’s no correlation between your earning and your income. You just have to get used to it.

A form of delayed gratification, in a way.

It is, I suppose. You’re squirrelling things away. But when I work on this show now, where are we, May? I don’t do it until November. But I’m prepared because I’m filming; my virtual band, filming people and clips and stuff we want to put in the show. It’s the preparation that is the hard work – and then when you come and do it, that’s a different set of skills.

Will you have performed that show anywhere else by the time you arrive in Australia?

Yes, in New Zealand. And I think we’re going to go on the road in the west coast (of the US) in September. So it should be pretty well run-in, but obviously at the beginning, it’s always interesting to see whether you’ve guessed it right. I’m showing lots of unseen footage from Not the Weekend Television, and some from the Rutles shows. Giving people fresh stuff is good for them. Obviously there’s a bit of standard stuff, a bit of Python stuff – but on the whole I’m doing things that I like and enjoy, and that’s why I’m very excited by this show.

Was there anything that surprised you about becoming a parent?

It was so long ago, now. My first wife was Australian, and my only son lives in Brisbane; he’s 50. My daughter’s 34. I think the saddest thing is when they leave home, you know, the empty-nesting? Because it’s kind of fun being a parent; you drive them to school. We moved to California because it was more fun driving a kid to school in California than in London (laughs). It’s not raining, for a start.

Do you have any strategies for lifting yourself out of a funk, when you become sad?

You have to face life as a privilege every day. It’s not going to last. George Harrison told me all about that: you can have the most money in the world, you can be the most famous person in the world, but you’re still gonna have to die. And that is, of course, the great equaliser for all of us. We spend a lot of our time in denial.

I worked out you only have 30,000 sunsets if you live to be over 80. That’s a good thing to remember, I think. Because we tend to forget that we’re on a planet, and we’re going round, and we’re buzzing through space – and all of this is going on while we worry about whether the mail has arrived (laughs), or whether our TV’s working.

We tend to forget where we are in the larger view of things. To remember (that) is to just consider how amazingly unlikely it is that we are here, and able to communicate and think, and actually see photographs of the beginning of the universe, which was about 13.5 billion years ago. I find all that very exciting.

I suppose you can’t exist in that kind of mindset all the time, though; sometimes you do need to worry about the mail, and the TV, and what you’re having for dinner, and so on.

Well, I think “worry about” is the question; you mustn’t worry about them. There are things you have to take care of, obviously, in your daily life. But if you’re grateful for your daily life, first and foremost, then you are in a better shape to enjoy it. It’s a privilege where we live; I was born being bombed by Hitler, and I’m very grateful I no longer have to wear a mickey mouse gas mask (laughs). Most people don’t really realise just not being at war is one of the greatest things that goes on in modern life.

You mentioned George Harrison; what did you take from the experience of being at his deathbed (in 2001)?

Well, the interesting thing was that he was not at all concerned, and he was grateful that he wasn’t going to have to be reborn on this planet – whereas I’d give almost anything to be reborn (laughs).

Religion was the only thing we didn’t agree on, and we’d argue, but it didn’t bother us that we didn’t have the same viewpoint. George was a Catholic who became a Hindu. He was deeply religious, but his calmness, and his magnanimity facing extinction was very interesting. He was a great lesson, watching somebody not anxious about passing on, but looking forward to the next stage of life.

I can see how that perhaps should be a model to aim for, when facing the end.

I think it’s very important. If you’ve been with people who die, the body takes care of you. I mean, I had pancreatic cancer recently, five years ago, and I survived that. But what worries you more tends to be your kids, or your wife; everybody around you tends to be much more upset than you are. And of course a lot of endorphins kick in, and you get calmer. (Your body is) preparing for this event, and this eventuality.

I tried to write a musical called Death: The Musical for about 15 years, until I gave up because nobody wanted to buy it (laughs). But it’s probably the most interesting thing that happens to you, after birth. It’s worth thinking about, and worth coming to terms with – otherwise it can be very frightening and terrifying, and you don’t want that.

I’m 36. Have you found an upside to growing older that might surprise me?

Yes, I think so. I think your dick drops out of controlling you. That’s always a good idea – eventually, about 50 or 60 – you stop being led around by your dick. Men, in particular (laughs). There are very many consolations with age. It’s not the end of the world, quite – but it’s close (laughs). I mean, I’m 81 and I look forward to being 82. That becomes the big achievement.

Your song Always Look on the Bright Side of Life from Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) has become one of the most-played funeral songs of all time. How do you feel about that?

(Laughs) Well, I didn’t write it as a funeral song. We were being crucified to it, so it had a great deal of irony. When you are being crucified, “look on the bright side” is actually probably rather a bit too much. I mean, what is the bright side? (laughs) But I think that’s what makes it so popular for funerals: people see the irony. I was amazed when it happened, and I was very thrilled. I like it, and I’m very proud that it is that, and became that in England.

Oh, well beyond England; my editor told me he’d been to three funerals here lately, and all of them used your song as the send-off.

Really? Isn’t that interesting? Humour is very close to tears, and I think at a funeral, you do need to laugh as well mourn and weep. There’s a place for comedy, and I’ve had a lot of good laughs from people who tell me what happened at gravesites, and what they said.

Have you considered what you would like as your epitaph on your tombstone?

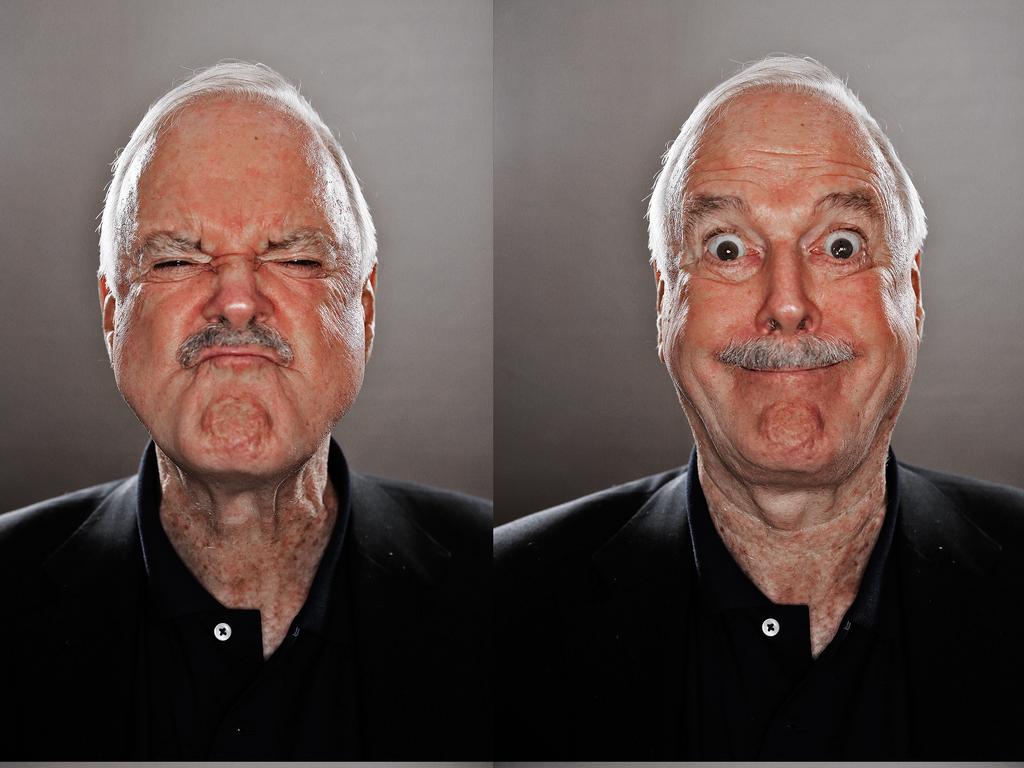

“I’d like a second opinion.’’ (laughs) When (John) Cleese and I toured Australia the last time, we had the series of “last words”. But nobody has a tombstone anymore. I think now, at the end of mine, it’ll say: “This is Eric Idle – see Google.”

I always liked Billy Connolly’s answer. On his tombstone, in a very small font, will be the words, “You’re standing on my balls’’.

(Laughs) That’s one that John and I told on stage. I’m glad it’s still in circulation. It’s very funny, Billy, being the funniest person of all time, really. After Peter Cook, anyway.

That’s high praise from you. I reckon you’re one of the funniest people on Earth.

I don’t think of myself as particularly funny. But I do find myself being funny. And I was just thinking to myself, “Why did I become funny?”And I realised that going to a boarding school at the age of seven, and finding out that your name Idle means “lazy, worthless, futile” ... and that people laughed (at it), they were already laughing. So I think you’re already conditioned to accept laughter, and live off laughter. I’m sure that’s something to do with it. It’s not an easy name at a boarding school, as you can imagine.

Knowing that you’ve made so many people around the world laugh, what does that mean to you?

The nice thing about being a comedian is when you’re walking through an airport and people recognise you, they tend to laugh and smile, because they’re remembering you doing something many years ago, or dressed up as whatever it was that comes to mind. I like that. I think that my job is sort of cheering people up, and I enjoy that as a role.

I guess it’s better than the alternatives: making people either angry or sad.

Well, that’s what politicians are there for – or perhaps religion (laughs).

Do you have a definition of a good joke?

No, because I don’t do jokes. Jokes are things that people pass around in pubs; they’re surrogate comedy. I like wit, which is one-liners, or where somebody says something in the moment. I like that in all art forms: in art, in music. You can find wit everywhere, and that’s my preferred form of humour.

You and your fellow Pythons were always prepared to cross-dress or take off your clothes in search of a laugh. Did that come easily?

Hmm. When you’re in a group like that, you challenge and push each other, and everybody grows and learns from each other. That’s what happened: we pushed each other, and some people took their clothes off more rapidly than others did (laughs). We did a lot of drag, but I think that’s because there were six people, and we were all fighting for parts: “Yes, all right, I’ll be the ostrich”, or whatever. There was a certain competitive element, and we wanted to be funny.

You’ve been playing music and writing songs for much of your life. Do you get a different sense of satisfaction from those things now?

Oh yes, because I know a lot more about it. I’ve also had a musical (Spamalot) on Broadway; we won the (Tony award) for the best musical on Broadway. We were just revived actually; Spamalot was on Broadway again. I get a great deal of pleasure from that, because I’ve learned about that musical form. But I’ve been writing a lot of songs recently, and I’ve been working with this band. I love working with these young musicians because we jam a lot: I find that the most fun because it’s instinctive. You don’t think; you just join in, and sing, and everybody has a good time.

I believe you’re fond of an Australian musician named Tommy Emmanuel. What’s your relationship with him?

I love Tommy. I met him many years ago, maybe about the 70s or early 80s, with Ricky Fataar: he was working on an album there, and I bumped into Tommy. And of course, I met him here on tours, and he’s just the best guitarist there is. He makes you want to burn your guitars, because he’s so good. But he’s also a funny, fine lad. He’s the most extraordinary genius.

Do you believe that hardship is necessary to create great art?

It might be necessary for comedy. Comedy comes a bit from mother abandonment, or hard times. When there are hard times – if you look at Russia under communism – there’s a great deal of underground humour. Humour is a way of reacting and responding against hard times, and owning up to it. ... It’s a helpful survival tool. I once wrote a book called The Road to Mars, and it deals with all that strange, “where does it all come from? How come we’re funny? (questioning).’’ Would we expect, for example, another civilisation from space to have humour? I think we would, because it’s about self-recognition, about seeing yourself in another situation. But we can’t tell, really. Or we might meet a whole race of people who didn’t have a sense of humour, like the Republican Party (laughs).

Or perhaps, in your former homeland of England, the Conservative Party?

Well, I haven’t lived in the UK for 30 years. All I do is hate them (the Conservatives), because I’m not allowed to vote. I just pay their taxes, and I wasn’t even allowed to vote against Brexit. I think that’s the worst thing that ever happened. They’re really stupid to me. Stupidity seems to be successful these days, unfortunately. But I think we should think about it more positively: we should say, well, obviously, if there’s evolution, intelligence is bound to come from stupidity, and not the other way round. So there’s bound to be (more) intelligent people left than there are stupid people. So there (laughs).

When was the last time you had to say no?

(Laughs) Usually I say, “No, thank you”, at least. But probably people passing drugs or drinks to me. I don’t do either anymore.

What was the best deal you ever made?

Buying a 1952 Martin was a good deal. I never regret buying guitars; I have about 30. Now we’re trying to get rid of them all; we call it “Downsize Abbey”. We’re getting rid of everything. As you get to this stage of life, you get rid of things, because you realise you can’t take it with you. In spite of the Egyptians, you can’t take these things with you.

What do you think you’ll be remembered for when you’re gone?

I don’t think we’re remembered for very long. I would like to think I’d be remembered as a good friend. That’s one of the things I appreciate most of all now – friendship – and family, obviously. But having good friends is really the best, and having good fun when we all get together, and play guitars and sing. Having a good time, and making good music, and making everybody smile and happy is not a bad way of going, you know?

Life at age 21 was …

Oh, brilliant. It was a life experience: I’d just got into the Footlights in Cambridge and I was doing entertainment. I got into show business. We did the Edinburgh Festival. It was really exciting.

Life at 41 was …

I remember Peter Cook giving me a blow-up sex doll. I didn’t want it, but it was very considerate of him (laughs). The 40s is not too bad: I was still playing, swimming and working out.

Lastly, life at 81 is …

Quite pleasant, actually, because nobody expects very much from you. Nobody listens to you (laughs). I mean, you’re virtually over as far as people in life think of you – but actually, you’ve got quite a lot of time to read, write and think about things. It’s much more fun than you’d expect – plus you’re no longer at the mercy of your dick, of course, entirely.

Eric Idle’s Always Look on the Bright Side of Life, Live! nine-date Australian tour starts in Hobart (October 31) and ends in Adelaide (November 20).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout