Shaun Micallef, who is Mad as Hell on TV, is a different man at home

HE’S made us laugh for decades. But behind Shaun Micallef’s wacky TV persona is a rather different character…

IN June 2013 the comedian Charlie Pickering was in Paris with his new bride Sarah, attacking the Louvre.

They’d been in the trenches for a few hours when they paused for a breather in the central foyer. Looking out over the battalions of tourists, Pickering spotted his friend Shaun Micallef, “a neatly dressed, daffy gentleman abroad” with his wife Leandra and their three boys, then aged 15, 13 and 11. Micallef, 52, has been a mentor to the younger Pickering and they stopped for a “What are the chances! In Paris!” conversation. It was a friendly encounter and they chatted amiably for five minutes or so. But Micallef was on a mission. He’d done his research meticulously and identified all the great artworks he wanted his kids to see – Venus de Milo, Mona Lisa, selected Rembrandts and Picassos, etc. He had then drawn a precise and intricate map, up stairwells and down corridors, marking out the most efficient route through the labyrinth. Micallef’s aim was to conquer the Louvre in less than 90 minutes, before either the kids, or he, got bored.

“It is just so Shaun,” says Pickering. “It is that attention to detail he applied to becoming a successful lawyer back in Adelaide. It’s the attention to detail that has allowed him to become one of the most successful comedians this country has ever produced. And it is that attention to detail on a family holiday that will give his kids a great cultural experience without them getting bored and hating museums.”

It is also just a little bit weird, a bit obsessive, and that too is Shaun Micallef. He’s a man who’s been on our tellies for two decades on Full Frontal, Micallef Tonight, SeaChange, Newstopia, Talkin’ ’Bout Your Generation, Mr & Mrs Murder, Shaun Micallef’s Mad As Hell and many other shows. He’s a writer, a producer, a director and an actor. He’s written books and starred in films. He’s presented the Logies. His showbiz credits are akin to Ricky Ponting’s batting record; sure there are a few soft spots but every performer would kill for that average. He’s seemingly omnipresent and yet he remains an enigma, and not just to the public.

Several of his friends, when I call them to say I am doing a profile on Micallef, wish me good luck. People who have worked with Micallef, some for decades, are generally fond of him but invariably say they don’t really know him. “We were in a forced marriage,” jokes comedian Denise Scott of the time they were thrown together on the Melbourne breakfast radio experiment, Vega, a decade ago. “It was never consummated, and after two and a quarter years it was annulled. There was no ugliness – just a quiet acceptance it was over.” They parted, she none the wiser as to who he really is. Another actor, who worked with him on Full Frontal in the mid ’90s, tells me he was surprised when he learnt Micallef was married. “I was genuinely stunned when I first met his wife,” he says. “I couldn’t quite believe he had a wife. He is almost like a Ken Doll. It’s hard to imagine Shaun having genitals.”

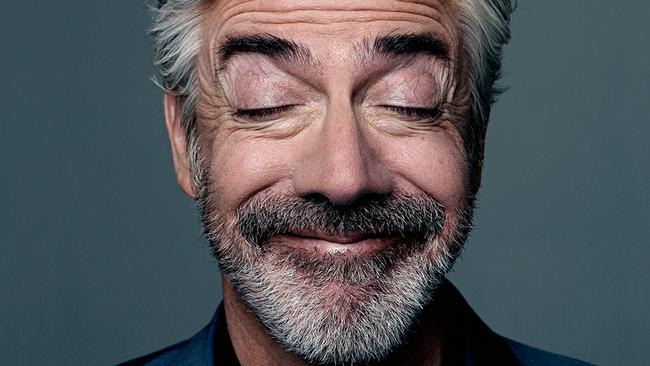

The Ken Doll of Australian comedy meets me in the ABC’s Elsternwick bunker in Melbourne where his comedic current affairs program, Shaun Micallef’s Mad As Hell, is produced. He’s tall and handsome and dressed like a lawyer at his son’s rugby match. The show is in hiatus until later this year and so he wears holiday stubble, not that he’s taking things easy; he’s midway through a tour for his third book, The President’s Desk, an alt-history of the US, and this year will star in a new ABC comedy called The Ex-PM, which he is writing. A documentary for SBS on spirituality, Shaun Micallef’s Stairway to Heaven, aired last month, and there are more to come. He competes in all forms of the entertainment game.

Micallef’s office is a glassed-in corner facing out to rows of empty desks where his writers and producers normally work. The place has an austere feel that screams “There’s no fat here!” to anyone who might drop by with a trimming blade. Just to add to the ambience, it overlooks the city’s Holocaust museum.

On air he appears super-confident and in control, but in person he is almost shy. “Even when his name is on the show he is playing a character,” says a friend. “Steve Vizard at a dinner party is the same as Steve Vizard on television. The Shaun Micallef you see on TV is a character.” Micallef tells me he’s forced to play a character because to play himself would be “too tedious for any audience”.

On the walls of his office are framed mementos of the men who have been his idols since he was a child: Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis in LIFE magazine, a James Stewart movie poster, another of Groucho Marx, and Time magazine asking of Peter Sellers, Who is this man? These men, he tells me, have guided him since he was a little boy growing up in the suburbs of Adelaide. “I was always conscious of the credits, even as an eight-year-old,” he says in that mellifluous voice, the one thing that remains constant on and off set. “I would look out for things that had been written by Spike Milligan or Peter Sellers. I was a big fan of Martin and Lewis and Sellers.”

When he was a kid his parents bought him a reel-to-reel recorder. “I used to hold the mic at the radiogram, tape it and play it back, again and again,” he says. “I would listen back to it all the time. I could do the show the next day at school and I could do all the voices.” Micallef was hopeless at sport and sought kudos in laughs, at home and at school. “At school, talk about the movies or what we heard on the Goons became our currency, we would trade those stories.” It was an unfair exchange as Micallef had learnt all the lines, word for word, and could do all the voices. At eight, he was already ahead of the pack. Just as Don Bradman honed his skills hitting a ball against a tank stand with a stump, hour after hour, Micallef obsessively mimicked the funny men of his youth, their eye movements, their walks, their timing and their gags so that these things became instinctive. “It became part of my matrix as a kid,” he says.

At home, too, laughs were encouraged. “It was a household where laughter was at a premium,” Micallef says. His dad, Alf, a Maltese immigrant, serviced cars at a Volvo dealership and worked his way up to be the spare parts manager. His mum, Judy, is a mortgage consultant. In their house, Micallef says, “jokes became a way of communicating with each other, which is good in some ways, but it can sometimes be a cover for not talking directly, so there is a legacy. Everything is sort of oblique.” Humour was not only used to amuse, but to put people in their place. “So there was always a sense that someone was having their legs chopped out from under them. Sometimes it could be a bit savage.” It is something he says he has fought hard to curb as he’s gotten older: not to be so savage with his comedy, to extract a laugh without leaving a barb.

His family life was warm and embracing and he was a popular kid at school, although somewhat a loner. His teachers and fellow students at Sacred Heart College must have seen something in him – they made him school captain.

“Fame is wasted on him,” says Adelaide barrister Alex Ward, tongue in cheek. “He doesn’t drink. He doesn’t womanise. He doesn’t do drugs. Why be famous? I should be famous, I adore those things.” Ward and Micallef met at the University of Adelaide and Micallef would go on to work in the Ward family law firm, doing insurance law “in the happier days for lawyers in insurance work”. But it was through university theatre that they became friends. Micallef loved anything to do with the theatre and would often turn up an hour early for rehearsals. His friends from those days, many of whom he still works with, say he was the standout performer; this beautiful, gangly kid with a deep, deep voice who never forgot his lines. “He was very hard-working for these performances,” Ward says. “He would do lots of preparation. He liked to check all his props, always seven times, and we would move or hide them… Obsessive-compulsive, that’d be my diagnosis.”

Ward tells another story that points to the same trait: the lawyers working for the family firm used a multi-storey car park and would arrive early to get the pick of the spots. Shaun always had to have one right next to the ramp. As a joke, his colleagues all got in before him one morning to take the spots adjacent to the ramp. Micallef drove around and around the near-empty car park, eventually ending up on the roof – next to the ramp.

As well as the theatre, Micallef and Ward had a program on Adelaide radio, The Comedy Crystal Set. It was supposed to be for kids, but they had higher ambitions and would do absurd skits about “Conan the Rotarian”. They were eventually sacked when the radio manager was listening in one day and a character said, “I don’t share your views on enlightened penology”.

It was during this time that Micallef met his wife, Leandra, who was a few years below him at law school – she was 18, he was 21. It was also when he gave up alcohol for good. He says he was a two-pot screamer and it seems he got drunk one day at a work function and fell asleep, or embarrassed himself in some way. He’s not a man who likes to lose control. “I added up the positives and the negatives and decided that drinking wasn’t for me,” he tells me.

Micallef beavered away in the law for 10 years, all the while dabbling in amateur theatre. He was on the cusp of being made partner in one of Adelaide’s more profitable firms and was about to get married to Leandra. One day he was watching Full Frontal and bemoaning the writing, saying he could do a much better job of it. “Leandra just said, ‘Shut up and do it’.” She marked a date on the calendar and said if he hadn’t done it by then he could never talk about it again. “I had never seriously considered performing and writing as a career. And as soon as she said it, it seemed like the most natural thing in the world.”

His good friend Gary McCaffrie, whom he’d performed with at university, had paved the way. “Gary is the one who did it and worked in a sandwich bar for two years until he got scripts read. As his coat-tail disappeared into the building I leapt on it.” Leandra stayed in Adelaide while Micallef moved to Melbourne to establish himself. He wrote, and then got a break, doing voice-overs, and then came to prominence with characters such as Milo Kerrigan the brain-damaged boxer and Fabio the Italian stallion. Soon he was fronting his own Full Frontal special and then his own program. Shaun Micallef, the star, was born.

It was a pretty risky thing to do, I say, leaving a lucrative law job for the unknown of showbiz. Were there family tensions, between you and your parents or with Leandra? “I could see how attractive it would be for your story, but no, it just seemed like the most natural thing in the world,” he says. Ken meets Barbie, they fall in love and live happily ever after.

Comedian Dave O’Neil has known Micallef for 20 years. They were writers on Full Frontal and later worked together on radio at Vega. “Full Frontal was survival of the fittest,” says O’Neil. “All the actors were looking to have a breakout character, and when they got one that worked all the writers were busting to write for that character.” The two actors who “broke out” and got their own Full Frontal specials were Micallef and Eric Bana – the two comedians, says O’Neil, who had the greatest screen presence.

While Micallef has a great on-screen presence, he lives life off screen “like some Mr Magoo character”, bumbling through life, not really noticing what other people notice. “He lives much of his life in his own head,” says O’Neil. “I remember him one day coming in and saying” – O’Neil drops into Micallef’s deep newsreader voice – “‘I can’t believe I went into the Highpoint shopping centre and my lovely little local pizza trattoria had opened a branch there’.” O’Neil says he looked at him with amazement: “I said, ‘You’re f..kin’ kiddin’ me – that’s La Porchetta. There’s, like, 500 of those in Victoria.’ He had no idea it was a franchise.”

Denise Scott says that, in the two-and-a-bit years they worked together, she can only remember one instance when he revealed something about his home life. “He and Leandra had moved into a new house at Williamstown – they’d been there for six weeks before Shaun realised there was another bathroom in the house,” she says. “He just hadn’t noticed.” Two of his closest friends, McCaffrie and Francis Greenslade (who plays Ian Orbspider and Vice Rear Admiral Bobo Gargle on Shaun Micallef’s Mad As Hell), tell me they haven’t been to his house for a meal. Greenslade says of Micallef: “I wouldn’t quite go as far to say he is Peter Sellers, with nothing inside him, but he saves it all for the performance.”

“He likes his worlds to be very separate,” says O’Neil. “He’s got his three kids and his wife and he leads a fairly quiet life, and then he has this showbiz stuff.” O’Neil says he was invited over to Micallef’s house for a barbecue once, but only because he’d badgered him after learning he’d bought a new barbecue. “Shaun was a good host, but he undercooked his sausages, I remember that. I mean, how can anyone not know how to cook sausages?”

“We have always been friends but we don’t mix all that much socially,” says McCaffrie. “He may well have a massive circle of friends that I just don’t know about.” The pair have written dozens of shows over several decades. “It may spoil what we have if we spent too much time together. Some actors need that constant reassurance. Shaun doesn’t need that; he has his family and that seems to be enough. I don’t want to paint him as some sort of Unabomber – but he likes to let his work do the talking for him.”

Micallef says he loves the buzz of performing, writing and being successful, but all the other trappings of showbusiness he can do without. “I would argue that most actors are pretty introverted people anyway,” Micallef tells me, as we sit together in the otherwise empty offices of Mad as Hell. “The temptation is always to assume that someone who takes to the stage enjoys being themselves in front of an audience. It is a surreptitious way of having people look at you without you having to look at them.”

He stays grounded by working with people who will tell him if “something is funny or if something is a piece of poop”, he says. “I don’t want to go the way of Tony Hancock, for example.” Hancock was a famous British comedian who killed himself in Sydney in 1968. “Hancock gradually divested himself of all his amazingly talented support people, his writers. He was constantly thinking, ‘What is it that makes me the funny one?’ He ended up by himself in Australia, working for Channel 7 and he knocked himself off. Not blaming Channel 7 for that at all… he just happened to be working for Channel 7.”

Micallef is still a student of comedy and tells me that one of his great joys was to have met one of his idols, Jerry Lewis. “It was around 2000 and Lewis was doing a tour and I rang up The Age and said, ‘Do you want an article on Jerry Lewis? All I want for it is the ticket to go to Sydney.’ ” He sat through the press conference and then got a private interview. “The guy across from me had talked to Stan Laurel about comedy! It was just incredible. I shook the hand of the man who’d chatted to Chaplin!” He relays this as if it were a religious experience. Comedy for Micallef is more a calling than a job.

This newspaper’s television writer, Graeme Blundell, describes him as the most intellectual of comics – a “wonderful” hybrid of Peter Cook and Stephen Fry with a touch of Graham Kennedy’s subversiveness.

Even those mocked by Micallef seem to like him, including Opposition leader Bill Shorten, whose mixed metaphors and bizarre one-liners have inspired a special “Shorten’s zingers” segment on Mad as Hell. But Micallef goes for both sides of politics. “Do you reckon that when Mr Abbott said he was going to shirtfront Mr Putin what he actually meant to say was that he was going to confront him?” Micallef says in one of his skits. “Then maybe he subconsciously recalled the last time he used the word confront, which was when he was talking about homosexuality and said ‘I find these things confronting’… and so his brain involuntarily switched the first syllable of confront with the first syllable of shirt-lifter to come up with ‘shirtfront’. Just a theory.”

Micallef says his life is very simple. He was a lawyer who did comedy for a hobby. When he took on comedy for a living he was completely satisfied with his lot. He had his family and he had his comedy; he didn’t need anything else to be happy. “My family, my wife and the kids became the thing I did outside of work,” he says. “Work just became my hobby and my friends were inside of that.” The two rarely mix.

“I just love spending time with Leandra and the boys,” he says. “For me, life is all about the small-ticket items. In 2013, the family went on a five-week holiday to Europe [which is where they met Pickering at the Louvre]. One day the boys and I took a train from London up to Liverpool – it was A Hard Day’s Night in reverse. We went to Anfield Stadium. We did the Beatles thing. We had lunch in Nando’s. It was one of the best days of my life.”

Charlie Pickering says he could not have found a better mentor in Micallef – he is always helping out younger comedians with advice or an encouraging word. “I think that he is a genius, that he is of the calibre of Spike Milligan or Peter Sellers,” says Pickering. “He’s that good. And he’s a really, really great dad and husband. If you can pull off those two things – genuine and consistent career achievement and a fulfilling family life – I don’t know what more you could really ask for from life.”