John Cleese: Fawltlessly funny

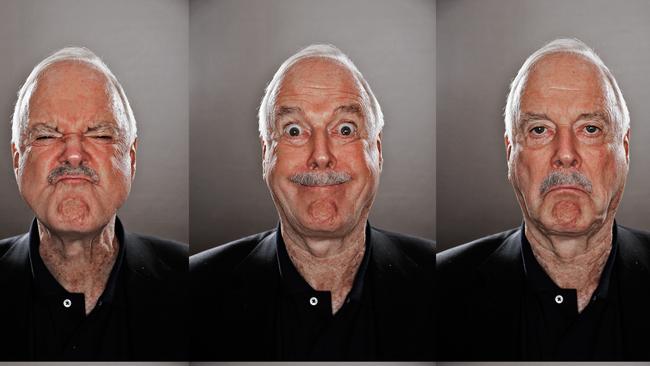

John Cleese disproves the theory one shouldn’t meet one’s heroes … he’s wittier, wiser and kinder than you’d expect.

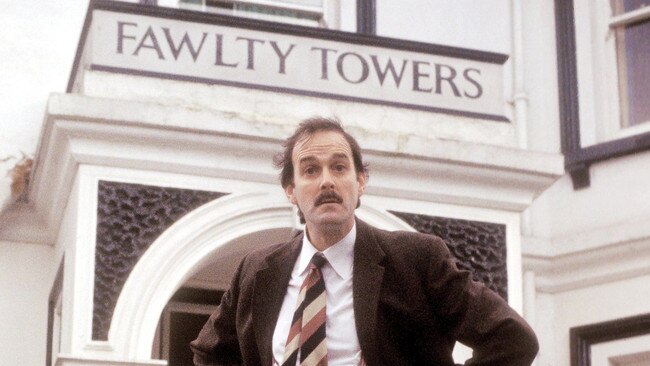

I haven’t studied the history of sitcoms. I couldn’t tell you the cultural precedents that led to this particular – and in my view rather wonderful – art form. I wouldn’t be able to give an intelligent view of why they have entertained millions. But one thing I do know: there has never been a show like Fawlty Towers, and neither will there be again.

I remember when it came out in the 1970s: in an instant, I was captured. Basil Fawlty, perhaps the most unforgettable character in British television history, was having a barney with a guest, and, even as a youngster, I was mesmerised.

This isn’t just a sitcom; it is a deconstruction of pomposity, sexual repression, embarrassment, class, etiquette, and an infinity of other things, all taking place in a small Torquay hotel, with six or so recurring characters (brilliantly played by Prunella Scales as Sybil Fawlty and Andrew Sachs as Manuel, among others) and a presiding genius at its heart.

One of the most wonderful things of the past five or so years of my life has been getting to know – and become close friends with – John Cleese. I had always wanted to meet him – he was top of my dream dinner party list – but, to be frank, it went beyond admiration. I wanted to understand how this man, who had grown up the son of an insurance salesman in Weston-super-Mare, managed to create not just Fawlty Towers (co-written with first wife Connie Booth) but also the output conceived with his fellow Pythons: The Holy Grail, The Meaning of Life and the Flying Circus TV show.

Oh, and did I mention Life of Brian? Growing up as a Christian, I always struggled to articulate my trouble believing that the gospels offered the unvarnished words of Christ. How could we be sure? There were no recording devices. “Blessed are the cheesemakers” made the point with such concision, such subversive insight, that I gasped when first watching it. As for “What have the Romans ever done for us?” and the People’s Front of Judea – or was it the Judean People’s Front? – I refuse to believe that there have been more biting pieces of scripted satire.

And what of Cleese himself? I first saw him in the flesh in a hotel in Bath (not Torquay). He and his wife, Jenny Wade, were staying there, and my wife, Kathy, urged me to say hello. “You love him! Tell him he’s your idol!” she said. I studiously refused, worried that I wouldn’t be able to hold my nerve and also that it might prove a letdown – never meet your heroes and all that. I had read media hit pieces insinuating that he was a bit cantankerous and egotistical, and I didn’t want to take the risk. So our paths crossed, so to speak, but we didn’t meet.

Then, a year later, something odd happened. I was making a BBC Radio 4 series about the philosopher Karl Popper and remembered that Cleese had expressed admiration for him during that unforgettable TV showdown in 1979 with the Bishop of Southwark and Malcolm Muggeridge after the release of Monty Python’s Life of Brian (the bishop and Muggeridge thought the film blasphemous). I was on the point of contacting Cleese via an agent at almost precisely the time he happened to send a tweet my way. He had read one of my books and wondered if we might meet to discuss it.

So, on a warm evening in 2017, we met at a London hotel, recorded an interview about Popper and then headed to a restaurant for a conflab. For many decades Reader’s Digest ran a feature called “The most unforgettable character I ever met”. It was clear within about 10 minutes that Cleese had rocketed to the top of my list.

It was dynamite. Cleese’s curiosity was stunning: in the first half-hour he asked about my life, world-views, attitude towards religion, relationship with my parents, political views, you name it. This is a man whose thirst for knowledge, to understand what Jean-Paul Sartre called the “inner world” of others, was limitless. He nodded, and encouraged, and laughed, and prompted, and smiled, and offered so much warmth that three hours passed in an instant.

Towards the end, when I finally got him on to his own life, loves, anxieties, disappointments and triumphs, he engaged fully with every question. He is one of those people whose capacity for small talk is non-existent precisely because he finds life so fascinating and mysterious that there isn’t time for polite triviality. I came to realise that this is the wellspring of his astonishing creative powers: in every moment of every day, his mind is fully engaged with the thrill of being alive.

And then, as we were getting ready to leave, an American tourist tentatively came over and asked for a selfie. I looked around and realised that quite a few other diners were looking over – Cleese has a rather distinctive frame and face – and he smiled at the woman and posed with her.

She offered gushing thanks, to which Cleese replied, deadpan, “I’m glad to have given some meaning to your pointless life.” The woman stared, her face worked, and then her shoulders started heaving with laughter as Cleese broke into a grin and gave her a hug.

Since that night we have stayed close. We Zoomed during lockdown, we email each other ideas, and we meet for lunch or dinner whenever he is back from his many foreign tours. He asked me to give an impromptu speech at his birthday dinner and did me the honour of heckling throughout.

One day we met for lunch and were only halfway through the conversation when it came to an end, so we met for dinner the same day to finish it. We have been in regular contact about his upcoming series on TV channel GB News, too, which starts soon. On this last point, some have wondered if Cleese has gone off the rails by engaging with a channel that some regard as beyond the pale. His logic is rather different: the broadcaster gave him editorial freedom to come up with a series of ideas for chat-style programs – so why not take the opportunity?

The money probably helped a bit, too: Cleese has never been shy about the huge cost of his third divorce, from Alyce Faye Eichelberger in 2008. He will discuss everything from the nature of creativity to the future of satire, and will take aim at woke ideology. He argues that wokeness has some positive aspects, but because it is so literal-minded, it leaves little scope for nuance or debate – not unlike evangelical religion.

Cleese is also putting together a new series of Fawlty Towers with his daughter Camilla, who has followed her father into comedy. Will it be as good as the original? That is a bit like asking whether Paul McCartney’s next album will be as good as Revolver or Rubber Soul. I just hope that the new series captures some of the old magic, and I certainly can’t help admiring Cleese – at the age of 83 – finding the impetus to put life back into the unforgettable Basil Fawlty. And, even if it is a dud, it won’t – can’t – sully the memory of the flawless original.

In Italy they admire their creative geniuses. In France ditto. In the UK – perhaps because of the Brits’ history of stability and suspicion of revolution – we seem to afford greater recognition to solid establishment types with their knighthoods and peerages (Cleese rejected the CBE in 1996, describing honours as “silly”). I think this is a cultural blind spot, when you consider that it is creatives who change the world and, in the case of comedy, evoke that priceless and mysterious phenomenon called laughter.

In this context I’d suggest that Cleese is not just the greatest comic to have emerged from these islands but a creative giant who stands alongside John Lennon, Virginia Woolf and the like.

“Don’t mention the war!” Will that line ever disappear from our cultural consciousness?

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout