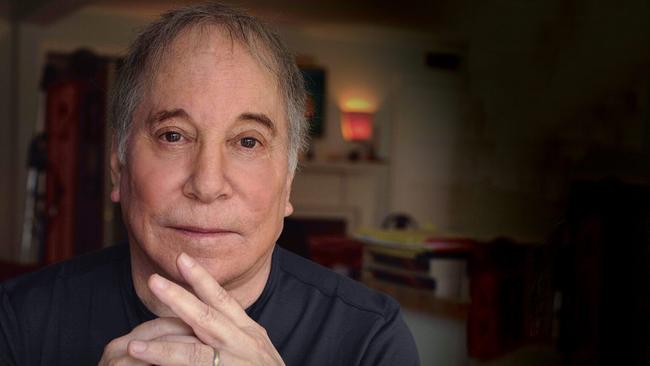

Paul Simon: ‘Maybe my disability is part of the process’

Simon has released his greatest album in decades. The 82-year-old singer talks about how it was inspired by memories of England, the impact of hearing loss — and why he’s writing a musical.

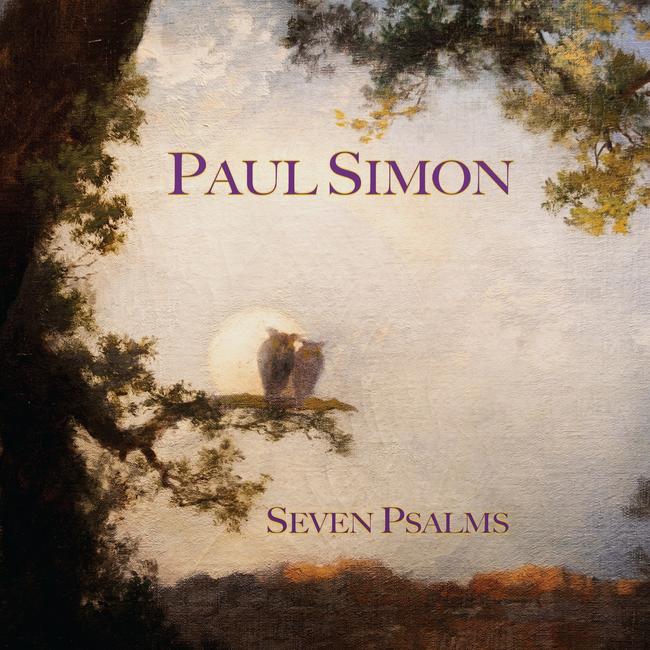

My artist of the year won me over with a 33-minute, uninterrupted musical meditation on life, death, faith and the great beyond. Seven Psalms by Paul Simon features seven movements, interlinked by an acoustic motif and lyrical reflections on the nature of God that came to Simon in a series of dreams.

It is a deeply moving piece of work: profound without offering easy answers, poetic without being overly serious, beautiful without descending into mawkishness. It brings in familiar elements of folk, blues and jazz, but transforms them entirely in a way matched only by Van Morrison’s 1968 classic Astral Weeks. And you cannot help but feel – although he denies this – that at 82 years old the great pop philosopher of the baby boomer generation is facing up to the end.

“I had a dream so vivid it made me get up in the middle of the night and write it down,” says Simon, the wise guy accent from Queens, New York, still in place, if rather more frail and hesitant than it once was, on how the album began. “A voice said, ‘You are meant to be working on a piece called Seven Psalms.’ My first thought was that I should look up the word “psalm” in the dictionary and then read the psalms in the Bible, but I still had no idea what I was supposed to do. I thought, well, since it’s not my idea anyway because it came in a dream, I don’t have to do anything. I’ll just wait.”

That was in 2020. For the next few months, from a ranch in Texas he shares with his wife, the singer Edie Brickell, (and from where he is speaking to me now) Simon worked on a series of guitar pieces without worrying too much about his dream’s mysterious command.

Isolated by the pandemic and unable to work with other musicians, he enhanced the guitar pieces with sounds from an instrument invented by the American composer Harry Partch called the cloud chamber bowl: amplified upside-down wine glasses, hit with a mallet to produce tones reminiscent of distant church bells. Then, sometime about 3am three times a week, a series of further dreams gave him commands on where to go from there.

“It is a cliche – I’m even reluctant to use the word – but this really was one of those occasions when I was a conduit,” Simon says. “The first words I wrote were ‘The Lord’. And I thought, OK, this is about belief.”

What I found truly fascinating about Seven Psalms is the way it provides a timeworn riposte to Simon’s earliest, most celebrated songs. Simon & Garfunkel classics such as The Sound of Silence, Homeward Bound and Bridge over Troubled Water captured the sweet melancholy of solitude, homesickness and companionship to a gentle acoustic setting, and Seven Psalms returns to those feelings from the other end of life.

“I lived a life of pleasant sorrows until the real deal came, broke me like a twig in a winter gale,” Simon sings on Love Is Like a Braid. And a guitar motif running throughout the album bears a close relation to Anji, an instrumental by the British folk guitarist Davey Graham that features on Sounds of Silence, the 1966 Simon & Garfunkel album. Simon learnt Anji over formative years in London, arriving in 1965 to rent a room in Brentwood, Essex. It all makes Seven Psalms feel like a reckoning with Simon’s past.

“The guitar motif on the album came from my years in London on the English folk scene,” Simon confirms. “Nothing in my repertoire can’t be traced back to something I’ve heard at some point, and the two big influences were street corner doo-wop from New York and the folk music I heard in England.

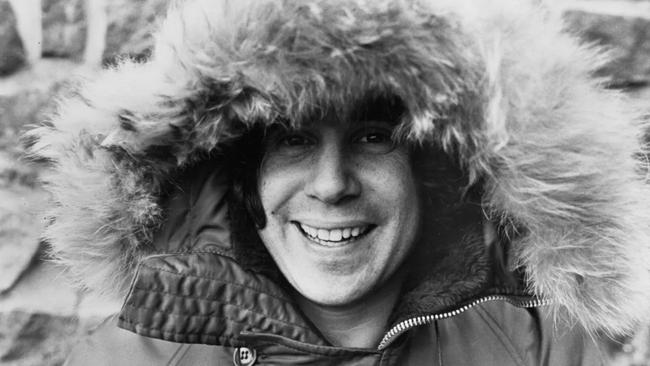

“I wrote Homeward Bound and I Am a Rock in England. I learnt how to fingerpick acoustic guitar from Martin Carthy, who was connected to the Watersons [singing family] from Hull, which of course led to Scarborough Fair, and I had never heard anything like those Old English songs. The closest I got was the Everly Brothers, who borrowed from Appalachian melodies, so that period was very powerful for me. I was 21, 22, and emotionally open to everything.”

Simon was welcomed with open arms by Britain’s bohemian folk scene after having been rejected by New York’s Greenwich Village folk world, in part because he came from the unfashionable suburb of Queens. It was in London in 1965 that Simon produced the now classic (and only) album by Jackson C Frank, another American expat, who was living the high life on an insurance payout after being severely burnt in a school fire.

“He was a grouch,” says Simon of Frank, a brilliant songwriter who ended up homeless and destitute. “He had all this money from an accident that left him disfigured, so he just wanted to get rid of it. That whole period in England did serve as one of the inspirations for Seven Psalms.”

Not that Simon holds onto the boomer conviction that the music you heard at a young age is far superior than whatever the kids listen to these days. “Whatever you hear from the ages of 12 to 16 will have the biggest effect on you,” he says.

“My kids get nostalgic about Nineties pop, and you know what? It is pretty melodic. Backstreet Boys and NSYNC were pretty good singers. Every generation loves the music they hear as a teenager, so it is not so different from me falling in love with any number of doo-wop groups I could name that you won’t have heard of.”

Most potently, Seven Psalms feels like a reckoning with death. “To a certain degree yes, but not really,” Simon says, countering my suggestion that the album is intended for a generation facing up to mortality, one to take its place alongside Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker and David Bowie’s Blackstar. “Firstly, I don’t ever feel like I’m speaking for a generation. Secondly, our ability to be in denial about mortality is very powerful.”

We are speaking shortly before thanksgiving. “Right now I’m thinking about how much I’m looking forward to it because the family will be together again, and I don’t go around thinking about death, even though at 82 it is hard to avoid. You know that saying, live every day like it’s your last? I always think, really, must I? Can’t I squander a couple of days doing nothing?”

Simon has been writing songs since he was 12. It is all he has ever done, and he says Seven Psalms was above all an exercise in songwriting craft. “For me the great achievement of the album is The Sacred Harp,” he says of a duet with Brickell, which depicts a mother and son hitchhiking to escape persecution in their home town on which he sings: “They don’t like different there/ They would have mowed us down.” “I know that’s a good, compassionate story about outsiders, and when I wrote it we didn’t have our current spate of refugees, we had people fleeing poverty in South America. Then you realise: there is always a stream of refugees somewhere.”

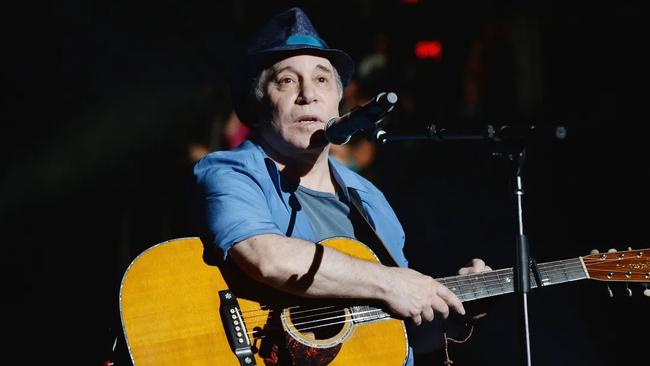

About a year into making Seven Psalms, Simon lost the hearing in his left ear. “I was, as you can imagine, pretty upset,” he says, not unreasonably. “Then I thought, maybe this sudden disability is part of the process. Maybe it goes with the effortless stream of information coming my way through the dreams.”

Needless to say, a single-track album based around acoustic guitar and complex reflections on divinity, without the rhythmical intensity that made his 16 million-selling 1986 album Graceland such a hit, is not the most commercial prospect. “Well, it is generationally inappropriate for me to write hits any more,” Simon says. “And I envisioned Seven Psalms as one long thought, combined with sounds powerful enough to make the thought come alive, so that’s how it had to be.”

Simon also insists the album is not a great leap forward. “One of the big misconceptions about me, which started with Graceland actually, is that I’m always seeking to change. It’s not true. I’m always continuing the piece I last worked on. I’m just leaving the parts I’m no longer interested in.”

When he finished his album Stranger to Stranger in 2016, Simon did think it might be time to stop and do something else with his life. “And I would have stopped. But then this dream told me to do this album and I began to think of all the things I learnt about guitar early on: strumming like the Everly Brothers, finger-picking like English folk, using melody like street corner vocal groups. That, alongside the cloud chamber bowls and so on, became the sound of the album.”

Then came the hearing loss. Initially, Simon resolved to retire completely, but the desire to complete Seven Psalms changed all that and since its release he has completed another song, composed four guitar pieces and is planning to make an album of duets with Brickell, “just for the sake of our kids”. He is also in the early stages of working on a musical.

“Looking back over my life, I seem to have a cycle of writing new material every three years or so and that’s what is happening now. But I’m not thinking, ‘What can I do to follow Seven Psalms?’ any more than I thought, ‘What can I do to follow Bridge over Troubled Water? I’ve just spent five days rehearsing Seven Psalms with two acoustic guitarists and I think I can play it live. I can no longer play with drums and electric guitar because of my hearing loss, but this might just be possible. I hope so because I miss performing, I really do.”

In the meantime Paul Simon has surprised even himself by making one of the best albums of his life, and my album of the year, at a time when he thought it was all over. As to the meaning and significance of Seven Psalms, he would rather we work it out for ourselves.

“I believe the listener completes the song,” Simon says. “Words come from my subconscious and my experience after decades of doing this is that the listener’s interpretation is more interesting than any meaning I intended. But I will say that there is a line on the album I consider more important than any other.”

The line comes in The Lord, the opening piece that also forms the returning motif of the album, and it is a simple one: “Nothing dies of too much love.”

“If you want to understand Seven Psalms,” Simon concludes, “it is all there in that one lyric.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout