Reworking the Catalogue: Van Morrison defies age formula

As he nears 70, in a rare interview Van Morrison reflects on music, happiness and the wisdom of age.

Skip to the end of his new album’s last track, a jaunty encounter with American blues and roots master Taj Mahal, and there it is, the unmistakable sound of Van Morrison laughing. Yes, laughing. There are so many stories about Van the Man snarling at the world — no one, with the possible exception of Lou Reed, has enjoyed such an antagonistic relationship with the media — that it comes as a shock to be reminded that he is capable of having fun.

“They never write about this stuff in the rock magazines,” he says, sighing. “They never write anything like that. They keep the mythology going — I am grumpy and never have a laugh — because they are so lazy. They might have to get a sense of humour.”

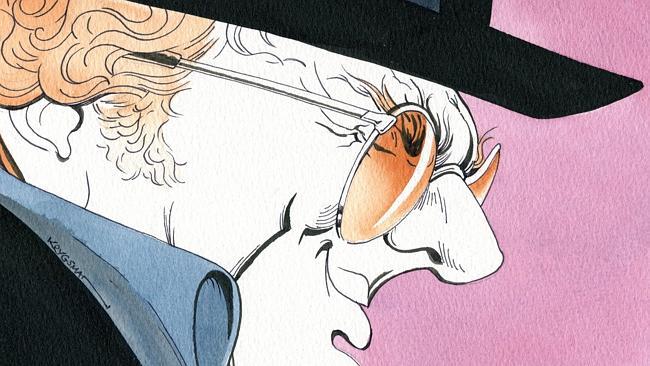

True, he is not exactly happy-go-lucky when we first meet in Glasgow ahead of his concert in the Celtic Connections festival at the Royal Concert Hall. At dinner the night before our interview, the poet from east Belfast seems distant and preoccupied. Encounters with journalists always put him on his guard. Still, the following day, as long as the conversation stays on the subject of music — questions about his personal life are, as ever, strictly off-limits — he is willing to engage in, if not chitchat, then a civil dialogue. Neatly turned out in felt trilby and smart-casual jacket, his eyes hidden behind sunglasses, he gradually unwinds.

It would be a reckless soul who ever talked about Morrison mellowing, but perhaps the prospect of turning 70 this year has had an effect. He is no longer the wild man with a taste for the hard stuff. Water and juices are his tipple now. He has a young son and daughter with his second wife, Michelle Rocca, a former Miss Ireland, whom he met in 1992. (He has an older daughter, American singer-songwriter Shana Morrison, from his first marriage to Janet Rigsbee, whom Morrison called Janet Planet. They divorced in 1973.) He certainly doesn’t look his age, but does he feel he is crossing a threshold? Does he feel a different person from when he was, say, 40?

“Absolutely. I didn’t know anything when I was 40,” he replies. “I still don’t know much. When you’re 40 you think you know everything. You realise that the older you get, how little you actually know. You can learn a subject, but the thing is, everything is always shifting and changing. It’s like the hourglass with the sand. Nothing in the universe is fixed. So how can your opinions or even the truth be fixed?”

His birthday, on August 31, will be marked with a concert on Belfast’s Cyprus Avenue, the street immortalised in a song of that name on Astral Weeks. He is certainly in a retrospective frame of mind on his new album. Duets: Reworking the Catalogue finds him exploring less celebrated corners of his ample repertoire. There is no Moondance, no Brown Eyed Girl. Instead, helped by admirers ranging from Steve Winwood to Gregory Porter, Joss Stone to Mark Knopfler — and Shana — he revisits the likes of Born to Sing and The Eternal Kansas City. He even persuaded veteran pop reprobate PJ Proby to join in on Whatever Happened to PJ Proby?

Morrison’s army of fans, of course, will be poring over every syllable, every nuance. Like Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen, the man who was born George Ivan Morrison, ascended into the pantheon a long time ago. In the 40-odd years since he made Astral Weeks — one of rock music’s most idiosyncratic albums — Morrison has charted a singular path, blending Celtic mysticism and poetry with blue-eyed soul, folk and his voice jazz. His voice, urgent and impassioned, sometimes trancelike, is one of the most recognisable in the business. Where Mick Jagger is the ultimate exhibitionist, Morrison is the anti-showman, the anguished role model for singers as diverse as Elvis Costello and Nick Cave.

And now he has been holding court in the studio. Of course, when grand old men reach the stage in their career when they make an album of duets, the results can be formulaic. Morrison’s beloved Frank Sinatra set the precedent with two bestselling discs in the 1990s, the guest stars phoning in their contributions on standards that, with a few honourable exceptions, sounded as if they had been injected with embalming fluid.

Morrison’s project took a much more seat-of-the-pants approach, most of the VIPs turning up for face-to-face sessions which, Van being Van, were dispatched as quickly as possible. The only exceptions were Winwood and Michael Buble who, due to scheduling problems, recorded their vocals separately (on Fire in the Belly and Real Real Gone respectively). It is a pity Buble missed out on meeting his idol. After all, in-concert he has even been known to joke about his “man crush”.

The idea for the album had been at the back of Morrison’s mind for years. It finally began to take shape in 2013 when he performed at the BluesFest at the Albert Hall. With Bobby Womack, Mavis Staples and Natalie Cole also on the bill, the time seemed ripe to start to get to work in the studio. Despite his failing health, Womack, who died less than a year later, sounds fully in command on the album’s opening track, Some Peace of Mind. Staples and Cole are equally self-assured on their numbers.

Not content to work with only well-established names, Morrison cast his net wider. American jazz-soul singer Gregory Porter, who has rocketed from nowhere in a couple of years, learned that Morrison was in the audience at the Cheltenham Jazz Festival. When the summons came, Porter, a long-time fan, was relieved to discover that the man he was dealing with was “a regular cat, a soulful cat”. Nervous at first, he relaxed when Morrison told him not to imitate the original recording of The Eternal Kansas City but to “put your own thing on it”.

With his long list of collaborations through the years — everyone from Ray Charles to the Chieftains, and Cliff Richard, too — Morrison believes the best way to capture any mutual chemistry is not to be overelaborate. “I don’t like lingering. I’m from the John Lee Hooker school of, ‘You get in, you get out’.”

The key to the process — one that is sometimes overlooked — is his passion for jazz. Rock fans may claim him as one of their most enduring superstars, yet he has rarely bothered to hide his disdain for rock culture. “I am coming from a different era than a lot of people,” he says. “The people I would be hanging out with when I was a kid would have been much older than me. There were a lot of people in my area for some strange reason who had recordings and were into this stuff. That was the kind of era I grew up in. It’s about jazz and blues as opposed to rock. I didn’t grow up on Top of the Pops. It was more esoteric, stuff that you had to think about. It wasn’t like turn on the radio and get the top 10. So that is where I am coming from — jazz, blues, folk, the beat thing. There was jazz and poetry. It was all kind of interconnected.”

It’s ironic that R&B, once corralled into a racially segregated subgenre of popular music, has become an all-conquering global force. Morrison, however, sees nothing to cheer about. “Terrible,” is his blunt assessment of the modern-day descendants of the musicians who inspired him in his youth.

“I can’t relate to it now, what they call R&B. It doesn’t have any rhythm in it,” he says. “It doesn’t have any blues. To me it is very unrhythmic. It’s very robotic. Words take on different meanings after a while. It’s like soul. I don’t know what that is now. To me, soul was like Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Bobby Bland, Solomon Burke, Bobby Womack. But what is it now? It is just a word. It can mean anything. What is jazz? Some of the stuff that they say is jazz, I don’t know what it is. Blues also. [Some people think] blues started with Jimi Hendrix. So the jumping off place was really loud guitar and feedback. To me that’s not the blues. Blues is like Junior Wells and Buddy Guy in a club, live.”

As for his own shows, the gigs he seems to enjoy most, especially as he hates going on the road, are the occasional low-key ones in clubs and hotels in, say, Belfast or London, where hardcore fans — some of whom fly in from as far as Australia, where he has not performed since 1985 — can see him close up.

“I have always liked small gigs,” he says. “It’s a dinner/supper club kind of situation and it pays for everything. I don’t like travelling, I never have, especially long-distance travelling. I like it even less because I am tired now. I don’t like booking things way in advance because sometimes you get there and you’re not in the frame of mind to do it or you’re too tired. I like to be able to book things at short notice as much as possible.”

You can never be sure where his mood will take him in live shows. At the Albert Hall last year, his decision not to play an encore left some fans feeling short-changed. His management, though, insists he does not set out to snub his audiences: “The encore thing is just about feeling,” they say.

There is certainly no sign of fatigue at the sound check at the Royal Concert Hall. Morrison is in a joshing mood, cracking jokes as he slips between guitar, vocals and saxophone. At one point he even asks his musicians if they have seen Stella Street, the BBC celebrity spoof series in which John Sessions turned in a hilarious impersonation of a sour-faced Van the Man. At the concert itself, my vantage point in the wings allows me to see just how casually Morrison navigates a show. His musicians invariably know what the first two or three songs will be, but from that point onwards he calls the tunes much like a jazz musician. “You get good at lip-reading,” his musical director Paul Moran tells me later. “Van is really an orchestrator, an on-the-spot orchestrator.”

The performance zigzags gently. At one point Morrison asks Moran to leave the keyboards, pick up his trumpet and add a chorus or two of muted, Miles Davis-ish horn. It takes a few moments for Moran to respond because he cannot make out what his boss is saying above the music. In the end, he gets the message.

All the while, Morrison barely addresses the audience, reaching out to it instead through a sort of telepathy. When he detours into a snippet of Parchman Farm, Mose Allison’s droll crime-doesn’t-pay classic, he indulges in a Joe Pesci impersonation, pretending to fire a pistol as the drummer hits rim-shots. Seeing the audience is slow to react, he grunts, “It’s a joke. This is just theatre.” Pure Van, in other words. Later, as the night draws to a close, the band moves into Ballerina, from Astral Weeks. Morrison caresses the lyrics and, as the melody begins to fade, he walks slowly off the stage towards where I am standing. Just after he has passed me, he undoes the top button of his shirt and continues down the corridor. Then he is gone. Soon he will be on a plane heading home to Belfast. The show is over for another night.

Duets: Reworking the Catalogue is released on RCA/Sony.

The Times