School of Paris artists found creative and sexual liberation abroad

For Australian expat painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Paris was a liberal city where they could escape the ‘stuffy moralism’ of England.

The doyen of Australian art history, Bernard Smith (1916-2011) memorably borrowed the titles of the first two books of the Old Testament, Genesis and Exodus, to characterise decisive periods in the development of art in this country. The terms are used in his first book on the subject, Place, Taste and Tradition (1944), and again in Australian Painting (1962), a fundamental reference work that has been republished in more recent decades with additional chapters, first by Terry Smith (no relation, 1991) and then by Christopher Heathcote (2001).

These evocative biblical titles refer respectively to the formation of an Australian school of painting at the end of the 19th century and then to the wave of expatriations that took place, perhaps surprisingly, just before and after Federation (January 1, 1901).

Most notably, Arthur Streeton sailed to England in 1897 and Tom Roberts in 1903 – specifically to work on an ambitious painting commemorating the inauguration of the new commonwealth parliament in Melbourne and the many portraits of British dignitaries that needed to be included.

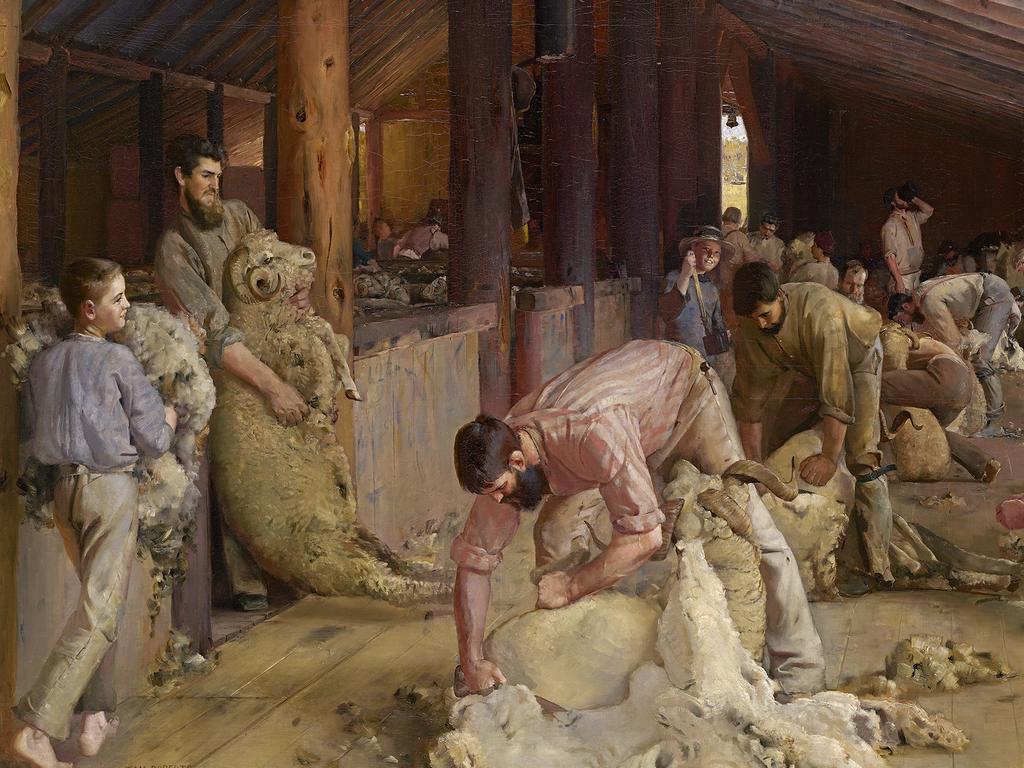

These were the men who had shaped what has usually been considered the first true movement of Australian painting, the Heidelberg School, today often misleadingly referred to as Australian impressionism; they were in fact barely aware of the French movement and their aesthetic was entirely different.

Others left, too, such as Charles Conder (as early as 1890) and Frederick McCubbin later, in 1907. George Lambert left Australia in 1900 and Sydney Long moved to London in 1910.

In the mid-20th century it was generally assumed that earlier colonial art had been essentially European and derivative. Today, after several decades of deeper study of John Glover, Eugene von Guerard and others, we can see the colonial artists were far more responsive to the topographical, climatic and social conditions of their new environment than had been assumed, and that the formation of a so-called Australian school begins from the early days of settlement. The main theme of this development, as I argued years ago in Art in Australia from Colonisation to Postmodernism (1997), was a succession of phases in the imaginative inhabitation of a new and strange land.

Thus our first vision of Australia was as explorers who survey and return home; then as colonists who may live here for a time but still think of Britain as their homeland; then as settlers coming to terms with a new and permanent home. This last phase corresponds first to the high colonial period and the art of von Guerard; but the Heidelberg School replaces the sublime with the familiar and forges a new sense of belonging and intimacy that can indeed be considered the consummation of the Genesis phase.

It may seem strange, again, that many of our most important artists left Australia just at this point, but despite the political progress of Federation, the economic situation was very difficult for some years. Several decades of economic growth following the Gold Rush in the mid-century were halted by the Depression of 1891, which reached its lowest point in 1893 with a banking crisis. Its effects were prolonged by the Great Drought of 1895-1903; after that year conditions rapidly improved and the economy was booming by the end of the decade (these details are drawn from a research guide on the website of the Reserve Bank of Australia).

The 1890s Depression naturally made life very hard for artists, but there were no doubt other reasons to travel to London, one of which was to seek further training at the great art schools there and in Paris; but another was undoubtedly to measure oneself against the dominant figures of international contemporary art. If the Australian school had matured, it was time to see how it stood up against the art of the metropolis.

Although the artists mentioned achieved some recognition in London and a foothold in its art world, they did not become as prominent as they would have hoped, and Roberts lived through years of dark discouragement. It was not until after World War II that Australian painters such as Russell Drysdale, Sidney Nolan and Arthur Boyd became truly leading figures in the British art scene, highly regarded by critics and the market alike.

A small exhibition at Bendigo Art Gallery focuses on another aspect of this Exodus period. The School of Paris: Australian Artists Abroad was conceived as a companion to the recent Paris: Impressions of Life, a loan exhibition of works from the Musee Carnavalet in Paris (reviewed here on April 20-21): it considers Australian artists who lived mostly in Paris rather than London and whom I have discussed in a chapter of John-West Sooby’s recent collection of studies, What Have the French Ever Done for Us? (Wakefield Press, 2024).

By the end of the 19th century, Paris had largely taken the place of Rome as an international centre for artists seeking advanced academic training or contact with new movements and styles of painting, or both. Australian artists who went to Paris too early, such as John Peter Russell around 1882, Rupert Bunny in 1886 and Emanuel Phillips Fox in 1887, missed the rise of the Heidelberg movement from 1885 onwards, and were never truly part of it. Russell and Fox were imitators of French impressionism, like the painters rightly known as American impressionists, while Bunny moved from an academic style to a kind of post-impressionist and decorative modernism in his last years.

The Bendigo exhibition is drawn from works in their collection, and Bunny is represented by a particularly fine example of the kind of picture for which he is best known. It is titled The Sun Bath (c. 1913) and all three figures were modelled by his beautiful French wife, Jeanne Morel. The scene is the corner of a garden where a carpet has been laid out on the grass and a Japanese painted screen has been set up to afford the young ladies some privacy while they strip and enjoy the warm sun on their bodies. The one on the right looks up as though suddenly realising that someone is watching but doesn’t appear particularly disturbed by this intrusion.

Bunny here, as so often, evokes a discreetly but intensely sexually charged world in which women are shown lounging in a state of idleness, enclosed in a private feminine space – as in the Art Gallery of NSW’s Bathing (1907) – or sipping cool drinks on a summer’s afternoon, yet always waiting, preparing themselves, anticipating the arrival of the man – who is never seen but only, as here, implied.

Paris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was, especially to the British and American mind, a place of tolerance and indulgence where one could escape from the stuffy moralism of Victorian England and the puritanism of America. For the French, one’s private life was one’s own business and no one else’s, and even until recently it would have been unthinkable to use a politician’s private sexual life against him. The press was thus reluctant to refer to president Francois Mitterrand’s mistress and illegitimate daughter until he virtually forced their hand in the last year of his life.

This tolerance extended broadly to homosexuality as well, and British homosexuals did not have to be as careful to hide their behaviour in Paris as in London; Oscar Wilde lived there for the last years of his life, from 1897 to his death in 1900. The city was the centre of an artistic lesbian world, particularly associated with American Natalie Clifford Barnie (1876-1972) and her beautiful but troubled English lover, Renee Vivien (1877-1909), whose lives were the inspiration for Colette’s Le Pur et l’impur (1932). Brassai documented lesbian bars between the wars, and Americans Gertrude Stein and her companion Alice B. Toklas were also Parisian residents.

Most of the prominent Australian female artists of the first half of the 20th century appear to have been lesbians from well-to-do families. Among these were Grace Crowley, Anne Dangar, Margaret Preston, Jessie Traill and others. Many of these women were also expatriates such as Dora Ohlfsen, who was commissioned to design the frieze above the entrance to the AGNSW (now shamefully defaced by an ugly piece of pseudo-political kitsch), and Janet Cumbrae Stewart who was in Paris by 1923 and lived in the French provinces with her companion Miss Argemore ffarington Bellairs, known to her friends as Bill, and who produced countless pastels of young female nudes, redolent with erotic yearning.

One of the most interesting of these sapphic Australian expatriates was Agnes Goodsir (1864-1939), an alumna of the Bendigo School of Mines who went to Paris in 1899, where she studied, like so many foreigners, at the Delecluse, Julian and Colarossi private academies. She worked between London and Paris from 1912 onwards but settled in Paris in 1921, living at 18 rue de l’Odeon until her death in 1939. She seems to have had quite a successful career in Paris, painting still lifes as well as portraits. In 1927 she made a visit to Australia, and held an exhibition at Macquarie Galleries, from which Bendigo Art Gallery purchased one of the pictures in the present exhibition, Girl on Couch (c. 1915).

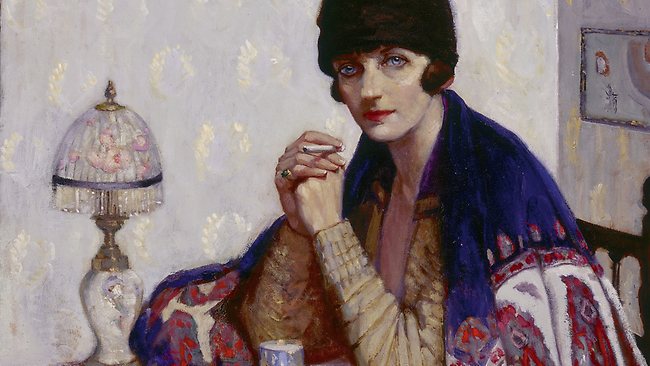

This picture had originally been exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1915 under the then-topical title A Letter from the Front, but Goodsir chose a more neutral one for her exhibition in Australia 12 years later. Bendigo bought this fine painting presumably because it was by a locally trained artist, and later acquired others such as Girl with a Cigarette (c. 1925), through a bequest in 1945, yet little was known about the artist until the director of the gallery, Karen Quinlan, started to research her and mounted a small monographic exhibition with a catalogue in 1998, In a Picture Land over the Sea: Agnes Goodsir, 1864-1939.

Goodsir’s career illustrates a problem that has affected several Australian expatriate artists, including Bunny and Russell: that they can achieve enough success abroad to live comfortably and respectably, but not enough to make any serious mark on the history of international art, while in their absence they are completely forgotten at home.

Most of Goodsir’s portraits – even of famous people such as Bertrand Russell, Leo Tolstoy and possibly Benito Mussolini – have been lost; several that survive, such as Girl with a Cigarette, are of her companion Rachel Dunn (1886-1950), known as Cherry, who lived with her from 1921 until her death, and then sent many pictures back to Australia, thus saving them from disappearing from sight altogether.

She stayed at 18 rue de l’Odeon until her own death and she was buried with Goodsir at Bagneux Cemetery where Wilde, too, was initially interred before his remains were moved to the now famous site at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery.

The School of Paris: Australian Artists Abroad

Bendigo Art Gallery to November 3

The School of Paris: Australian Artists Abroad

Bendigo Art Gallery to November 3

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout