Cultural cringe is back with the idea of ‘Australian impressionism’

Australian museums seem determined to force the work of Roberts, Streeton, Conder, McCubbin and other lesser figures – formerly known as the Heidelberg School – into the bed impressionism.

Australian museums seem determined, in spite of the objections of various scholars over some years, to force the work of Roberts, Streeton, Conder, McCubbin and other lesser figures – formerly known as the Heidelberg School – into the “Procrustean bed of impressionism”. Perhaps they think it will enjoy greater prestige under an internationally recognised label, and are afraid that the old appellation sounds too provincial.

This feels uncomfortably like another case of cultural cringe, and masks the fact, as I have often pointed out, that the Australian painters of this period were more original and interesting than their counterparts in America precisely because they were not imitating the French. It was all too easy for Americans to copy French Impressionism; so did those Australians who had the opportunity, like Philips Fox and John Peter Russell. But they are not the leaders or most important figures of the Australian movement.

It was not only because they were isolated at the ends of the earth and had to find their own way that these painters were original: they also had the benefit of a real subject, the question of living in a new land at the time when the colonies were beginning the process of federating into a nation. This national concern informs their most important work and has no equivalent among the American Impressionists, or indeed among the French Impressionists, who were conspicuously apolitical.

Stylistically, Roberts and Streeton have nothing in common with Monet. They drew their inspiration, as is well known and plain to see, from a combination of slightly older realist and plein-air traditions with the contemporary aestheticism of Whistler and even elements of symbolism and art nouveau, as we see respectively in Streeton’s allegorical or mythological subjects and the school’s designs for exhibition catalogues and other publications.

They were not interested in ephemeral climatic phenomena or momentary subjective experiences. Even the word “impression”, used in the title of their 9 x 5 Impression Exhibition in 1889 was borrowed from Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose own style was the antithesis of impressionism: “When you draw, form is the important thing; but in painting the first thing to look for is the general impression of colour.” What Gérôme meant, like the neo-classical plein-airists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was that a painting should start like this, but not end there, which is why he remained critical of the impressionists.

On the contrary, as I pointed out recently in reviewing the AGNSW’s Streeton exhibition, the Heidelberg painters were drawn between two quite different approaches to landscape: in private pictures, they often painted moody twilight scenes; in what we could consider their more programmatic pieces, those which more consciously and deliberately speak of living in Australia, they choose bright sunlight and landscapes at midday – difficult conditions for painters, because all shadows are flattened and colours are bleached by the intense light, but also the least ephemeral and fleeting time of day.

Nor were the true Impressionists only interested in subtle and impermanent effects. Their vision was also shaped by optical theories about complementary colours. Monet’s early Magpie (1868-69), the highlight of an exhibition in Adelaide in 2018, is a virtuosic demonstration that the warmth of sunlight can be evoked even in an essentially monochrome snow scene: the yellowness of the sunlight on the snow, almost imperceptible by itself, is evoked through the complementary violet of the cast shadow of the fence.

These optical theories had no effect on Roberts and Streeton. If we look at the latter’s Golden Summer, Eaglemont (1889), for example, the long shadows of the tree cast by the rising sun on the intensely yellow field should be violet; there is no sign of such a hue in the study, and only the faintest warmth in the grey of the shadow in the finished work. Oddly, the exhibition implicitly concedes the inaccuracy of the impressionist label with a room near the end titled ‘French Impressionism and its influence.’

This exhibition sets out to be revisionist in a couple of ways, with mixed success. It includes more peripheral figures and also brings in more of the women painters associated with the movement. On the whole this is a good thing: it is useful to understand any art movement beyond its headline acts. But their inclusion does not change the story in any significant way, any more than that of other important but secondary figures like Julian Ashton, Arthur Loureiro or indeed Philips Fox or John Peter Russell.

The other question that has clearly caused the curators or the management of the museum some anxiety in these hypersensitive times is that of the Aboriginal presence, or rather absence. For whereas Aborigines are ubiquitous in colonial painting, they almost completely disappear in the Heidelberg period, probably reflecting a new-found confidence and sense of being at home in a land we are learning to inhabit.

The Heidelberg school used to be loudly celebrated as the first truly Australian art movement, underestimating the achievement of such colonial predecessors as Eugene von Guerard. Now this has become unacceptable, so the solution is a kind of moral bluff: they are not really a beginning after all, because as a wall label assures us, they exist “within a far longer history. The thriving art traditions of Australia’s First Peoples, custodians of the longest continuous culture on earth, have existed for 65,000 years.”

Except that this is completely disingenuous. The Heidelberg painters have nothing whatsoever to do with the art produced by the Aborigines before the arrival of settlers, and were barely aware of it. They are not part of that cultural tradition. The art of the indigenous people was in any case of an entirely different order, with its own conventions and social functions, and does not have a history in the same sense as European art, which moves through dramatically different phases in dialogue with a dynamically evolving civilisation. Finally the Australia which these artists are involved in defining and celebrating is a European, not an Aboriginal concept, from its name all the way to its social, economic and political structures.

All that said, the exhibition itself is a very fine one and not to be missed: comprehensive in its coverage and well set out, with for example a wall of portraits near the beginning and an intimate space to enjoy a large group of the beautiful oil sketches produced for the 9 x 5 exhibition. Throughout the hanging, works generally speak to each other in a sensitive way, particularly when originally painted side by side by leading members of the group.

Conder and Roberts’ views of Coogee Bay, painted together in 1888, form one such indispensable pair. It is obvious that they were working close together, and clear if you look at the position of the central tree and the nearby shrubs that Conder sat on Roberts’ left and further up the hill, so that he could not see the end of the headland that appears in Roberts’ painting.

The comparison shows Roberts to be far the better painter, with a stronger and clearer vision. Conder’s picture is rather flat and lacking in structural definition; Roberts feels the shape of the foreground hill in an almost tactile manner as it falls away; he conveys the distance down to the beach, the brightness of the sun on the sand and the blue of the sea.

Conder comes off better in another pair of works by the same two artists, although still second to Roberts: Conder’s Holiday at Mentone (1888) and Roberts’ The Sunny South (1887) in which the three figures are, from left to right, Streeton, McCubbin and Abrahams. Conder’s picture evokes the strange awkwardness of a day at the beach before the adoption of the modern swimming costume; swimming was still done naked in segregated bathing enclosures or – as in Roberts’ painting, when alone in some private spot.

It is Streeton who is matched with Conder in what I have always regarded as one of the most important juxtapositions of this movement. Once again, the two artists are painting the same site and subject, but they see very different things. It is summer at Eaglemont in 1890, and the caretaker of the farm, Whelan, is their model. There is a massive cut log in the foreground and some kind of structure in the background, although we will never quite know what, since it appears differently in the two pictures.

Conder’s painting is charming but anecdotal and decorative. Typically, he has Whelan’s granddaughter playing in the long grass in the foreground, while Whelan himself stands, an elderly figure with a long beard, in the background. Streeton, in contrast, sees this as the opportunity to celebrate the hard-working selector who builds his home in Australia not by money or privilege like the squatter class, but by his own hard work. He makes Whelan younger; he has him sitting on the log, resting and smoking after his efforts; the axe with which he has been working leans emblematically against the log beside him.

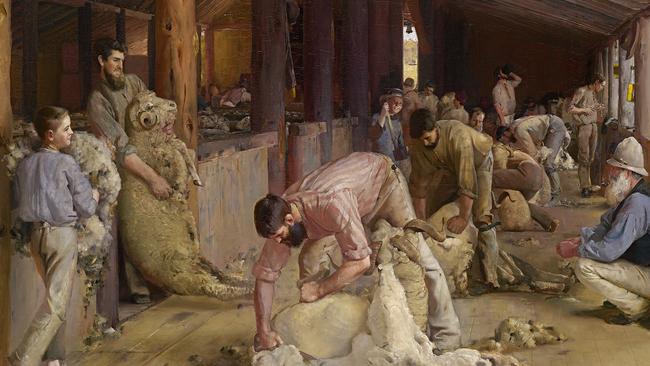

Not enough is made of the theme of labour in the exhibition, and it is a shame that Roberts’ Shearing the rams (1890) and his Charcoal burners (1886), his two most important works on this theme, are separated, perhaps because of the dubious point that the curators want to make about history at the end.

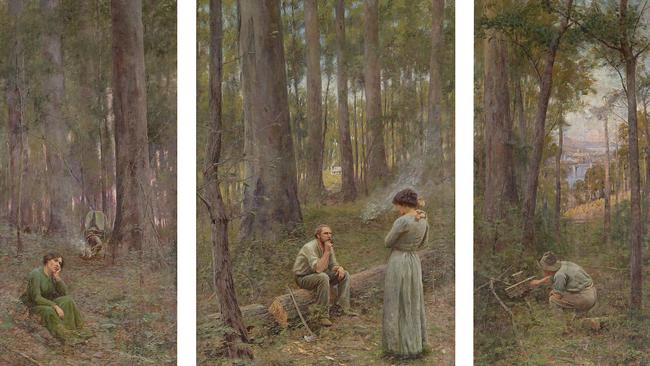

McCubbin had no doubt about the importance of this theme, however, and in The Pioneer (1904), his retrospective summation of the Heidelberg movement, he reprises the main figure of Whelan on the log for his central panel. In the first panel of what is very deliberately conceived as a triptych, we see a young couple leaving the city to start a new life as selectors on the land. They are not yet real country people: he is trying to start a fire and she sits sullenly in the foreground.

In the second panel they have grown up, grown into the land, and grown together. She now carries their child; he is sitting on the log, smoking his pipe with his axe beside him, exactly as in Streeton. And they are looking at each other; the difficulties they have shared have made them both better people. These, it is suggested, are the people who will be the backbone of the new nation.

In the final panel, a young man who is evidently the infant of the central panel visits their grave overgrown with weeds but on which we can still make out the word “sacred”. In the background, floating on the water, is the shining city which could not have arisen without the labour of these pioneers. Another artist might have made this a triumphalist work, but in McCubbin’s hands – and perhaps this is quintessentially Australian – the final note is one of melancholy.

She-oak and sunlight

National Gallery of Victoria to August 22