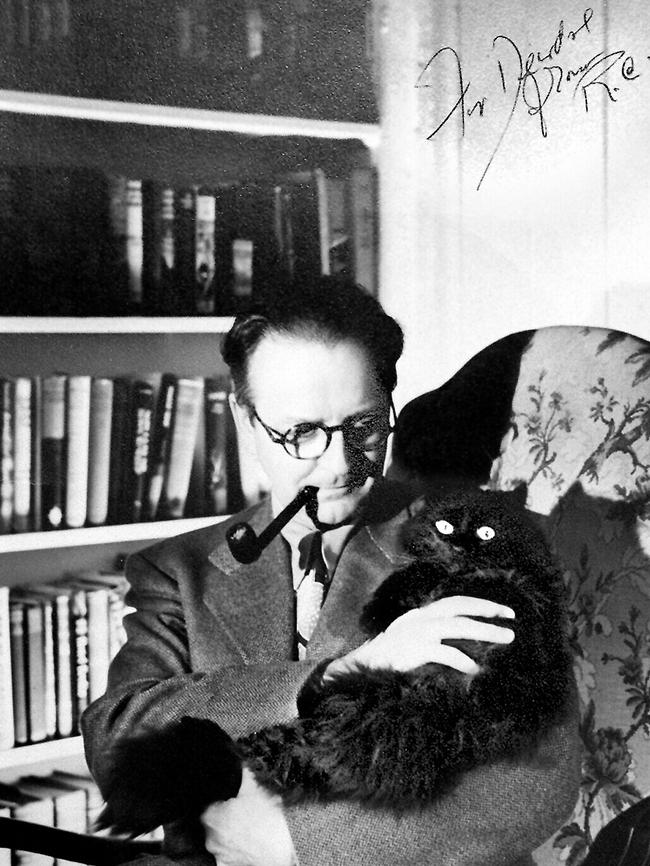

Dark and brooding? Not the Raymond Chandler I knew

Sybil Davis, whose mother was secretary to the master of noir, recalls a lively father figure who enjoyed the finer things in life.

“Call me Ray,” the smiling, immaculately dressed writer said when he met 11-year-old Sybil Davis for the first time.

Davis, 79, now a retired lawyer, is perhaps the last living person to have intimate memories of Raymond Chandler, the master of noir.

The daughter of his secretary, she came to love him as a father in the final two years of his life, and was only dimly aware of his fame.

A celebrated writer of crime fiction, Chandler created the archetypal noir detective in Philip Marlowe.

In novels including The Big Sleep and Farewell, My Lovely he became arguably the first serious writer to use Los Angeles as his canvas, capturing the dark side of a growing metropolis in the 1930s.

Yet, by the time Davis’s mother, a beautiful Australian named Jean Fracasse, answered a newspaper job advert in January 1957, Chandler’s best days were long behind him.

Widowed and battling alcoholism, he was working on his penultimate novel, The Long Goodbye, and in need of a secretary to force him to sit at a typewriter.

Fracasse got the job.

Chandler would take her and her two children out to dinner at restaurants in La Jolla, the well-to-do neighbourhood of San Diego where he spent the final years of his life.

Sometimes, it would be just the author and Fracasse’s daughter. Davis speculates on these occasions that her mother had had enough of Chandler, having worked for him all day.

The other diners must have assumed they were father and daughter. Chandler would tip the band to play his choice of music while leading Davis in a waltz, his favourite dance.

“He would treat me as if I was an adult,” she said.

“The lady will have a Shirley Temple,” Chandler would tell the waiter, ordering a non-alcoholic drink for his young companion.

Chandler, born in America but educated at Dulwich College, London, had a well-earned reputation as a drunk, having got a taste for booze as a soldier during World War I. Like his father before him, he was an alcoholic. It cost him his job as a Los Angeles oilman in the 1930s, harmed the quality of his writing and ultimately contributed to his death at the age of 70 in 1959.

Yet, when in charge of the girl he fondly called “my Sybil”, Chandler, who had no children, remained sober.

“I saw a side of him that the public has never been told about, where he was not at all this suicidal, down-in-the-dumps drunk,” Davis said. “He had a wonderful sense of humour. He loved to laugh. He was the antithesis of how he’s been portrayed as being the gloomy, solemn, on-the-verge-of-suicide writer. I did not experience that in him at all.

“And you have to remember that I was a child, so probably had he been heavily drinking or anything like that, I would not have been permitted to be around him.”

Chandler had attempted suicide in 1955 in despair at the death of his wife, Cissy. He was well known for having affairs with his secretaries, though his love for Cissy was never in doubt. After her death he developed a relationship with Fracasse. They were soulmates, according to Davis, but marriage was not to be.

Her mother, who had spent years looking after her ailing husband, Davis’s father, before his death, was not prepared to become a carer again.

Chandler proposed, Davis says, with his wife’s wedding ring. She has a picture of her mother wearing the ring as well as the jewellery itself, part of the collection of items Chandler left to the family. Davis considered putting the ring up for auction but decided it was too precious to part with. Other items did go under the auctioneer’s hammer in New York this month, including Chandler’s typewritten list of “Things I Hate”, which features “Irish songs”, “golf talk” and “baggy trousers”. He also listed “people” and “me”. Those two were ruled out by hand, but perhaps fuel the contemporary perception of the writer as drunk and miserable.

That is why Davis is sharing her memories, to counter a public image she insists is far from fair.

Their final meeting came shortly before Chandler’s death. Even to a child’s eyes he was a shadow of himself, having fallen ill while accepting an award in New York.

Chandler attempted to reassure the little girl, clearly shaken by his ill health, and gave her a hug. It was the last time they were together.

Yet in many ways, Chandler has never left Davis.

Fans frequently get in touch, amazed to be speaking to someone who shared a dance with their favourite writer. Davis welcomes the chance to keep the fire burning for him.

“Chandler was quite something,” she says.

“And he followed me through my entire life.”

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout