How the Bible made its way around the world

The Bible resonates with one-third of the globe’s population. Christmas is as good a time as any to reflect on why this might be.

“One hundred years from my day,” Voltaire reportedly remarked, “there will not be a Bible on earth except one that is looked upon by an antiquarian curiosity-seeker.”

Things haven’t worked out that way. The Bible is the foundational scripture of a religion claiming one- third of the planet’s population. Millions of copies are printed and sold every year, in hundreds of languages. Millions more are downloaded as apps and audiobooks. The Bible is printed and read illegally in some places, mocked and vilified in others, argued over everywhere. Its texts are studied, memorised, preached, interpreted and reinterpreted in churches, seminaries, small groups and prisons in every part of the world.

In The Bible: A Global History, Bruce Gordon chronicles the Christian Bible’s progression from a collection of ancient Hebrew and Greek texts – our word, “Bible” is derived from the Greek “biblia”, “books” – to its present status as, in the author’s appropriately ambiguous phrase, “the most influential book in the world”.

Gordon, a professor of ecclesiastical history at Yale, is an accomplished historian of the Protestant Reformation; his 2009 biography of John Calvin is the finest in modern life of the reformer. The Bible, in many ways a history of Christianity itself, is a marvellous work of scholarship and storytelling. Gordon chronicles the Christian canon’s beginnings and the early efforts to collect manuscripts into codices. He describes the Bible’s profound influence on the largely illiterate population of medieval Europe and its transformation into a source of individual spirituality in the Reformation and after. He relates the cultures of Bible-reading that sprang up in Europe and the New World and finally the Bible’s spread to India, Africa, South America and East Asia by the work of numberless translators, zealots, preachers and missionaries.

Biographies of books are, if I’m not mistaken, a recent trend – I think of D.J. Taylor’s book about George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and of Princeton University Press’s excellent series, Lives of Great Religious Books. Gordon has written the life of the book of books, and the sense in his narrative that this book is alive, as if somehow it has agency and finds ways to make itself known and felt, is inescapable.

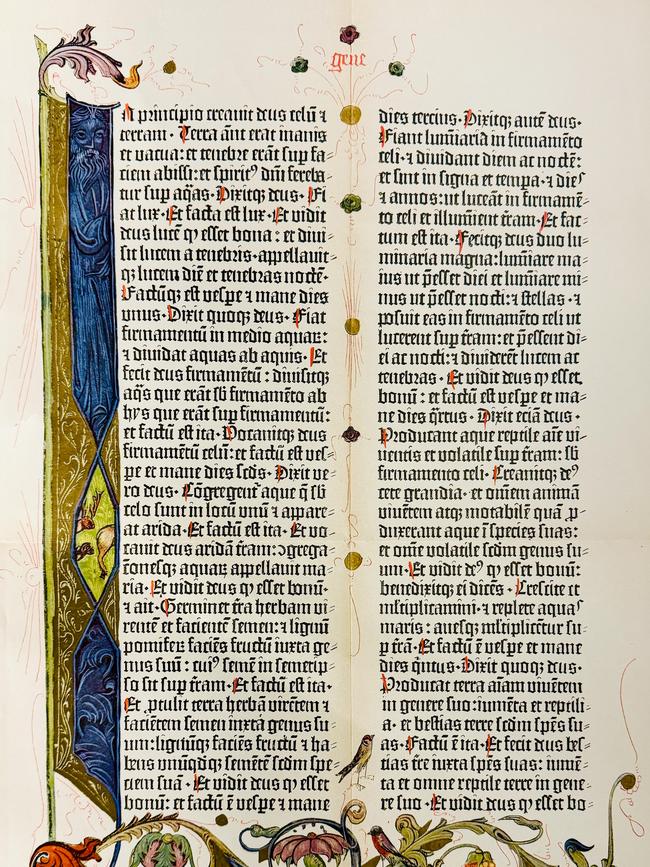

It’s well known that in the Middle Ages only a small number of clergy could read the Bible, or indeed could read at all. Yet “one of the greatest mistruths perpetuated by the Protestant Reformation”, Gordon writes, “is that the Bible disappeared during the Middle Ages”. As a hardened Protestant myself, I’m not entirely ready to relinquish this “mistruth,” but Gordon’s contention is valid: in medieval life, the Bible “was everywhere: heard and seen in worship, performed on temporary stages erected in village squares, recounted in song, shown in pictures on church walls. It was in medicine, colloquial speech, and roadside chapels and crosses.”

A book titled Historia Scholastica, by the 12th-century Frenchman Peter Comestor, was among the more important works through which the Bible exercised its influence on late-medieval Europe. Translated into several European languages, the book was a retelling of the Bible’s story that drew on classical sources and the teachings of church fathers.

“Not only was it required reading in the elite universities,” Gordon writes, “but over the course of the Middle Ages, it transmitted knowledge of the Bible into vernacular cultures through literature, drama, and sermons, for which it provided a compendium of stories.”

That the Bible and Christianity have diminished in importance over the past century is one of those things every Western social and political observer knows, or thinks he knows. Gordon’s global perspective preserves him from that error. For decades, an array of Christian faiths, all holding to the divinity of a resurrected Jesus Christ, have undergone explosive growth in China, Africa and South America. These traditions, Gordon writes, “identify with parts of the Bible often ignored by Western liberals, particularly passages about healing and spiritual warfare, as well as apocalyptic expectations and readings that generate a palpable suspicion of the secular world”.

Gordon’s history frequently upends the liberal account of religious decline, nowhere more so than in his explanation of the Bible’s role in the so-called Enlightenment. That “so-called” is the reviewer’s, not Gordon’s, but his narrative avoids the usual equation between biblical adherence and intellectual shallowness.

Galileo, for example, who was forced by ecclesiastical authorities to renounce his ideas on a heliocentric solar system, didn’t view himself as departing from biblical orthodoxy.

“Despite his final forced recantation”, Gordon writes, “the story of Galileo is about different attempts to claim and defend the Bible. His was a revolution from within rather than an external attack on scripture itself.”

The question with which Galileo and other thinkers of his era grappled “was not really whether the Bible was still relevant in a world in upheaval, but how it was so.”

Gordon’s narrative teems with long-suffering scholars, translators and missionaries but also with schismatics and sociopaths moved by biblical texts to do remarkable, and sometimes terrible, things. Always, however, the result is that the Bible advances further into societies that were formerly resistant to it.

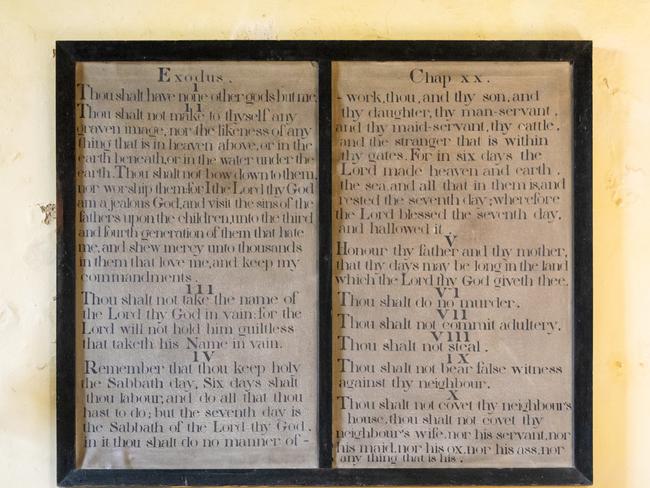

The chapter on China and East Asia makes this particularly clear. Hong Xiuquan (1814-64), leader of the Taiping Rebellion against the Qing dynasty, converted to Christianity when he read a tract that quoted liberally from Genesis, Isaiah, Matthew and Romans. On reflection, however, Hong concluded that he himself was the savior promised by the Hebrew prophets; he was, in his mind, the brother of Jesus and the second son of God.

Hong had the Ten Commandments rewritten to fit his ascetic sensibilities and planned to have the Bible itself rewritten to align more closely with what he considered authentically Chinese virtues. His Taiping army waged a savage war on the population of Nanjing, killing 40,000 Manchus, whom he reckoned “devils”. Hong derived his vision of a new kingdom of God from Revelation 21:2: “I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband”.

The upshot of this unhappy episode was that the Qing government, having been aided by Western powers in its fight for survival, felt obliged to give Christian missionary agencies freer access to the country: more Bibles in China. And Western missionaries, rightly realising that the Chinese populace wasn’t asking to be Westernised, adapted their efforts and became savvier evangelists.

A more edifying episode: in 1907, the city of Pyongyang experienced a Protestant revival, precipitated by the preaching of Presbyterian minister Kil Sun-joo. Thousands were converted. The consequent thirst for biblical knowledge led to a new translation, the Korean Bible of 1911.

More than 600,000 copies were produced, Gordon reports. I have to believe some of those copies, more than a century later, still float around, illicitly, in the present-day police state called North Korea and that the believers in that beleaguered country have read the promise of Psalm 37: “The wicked plots against the righteous and gnashes his teeth at him, But the Lord laughs at the wicked, for he sees that his day is coming”.

–

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout