The agony and ecstasy of a man who lived for music

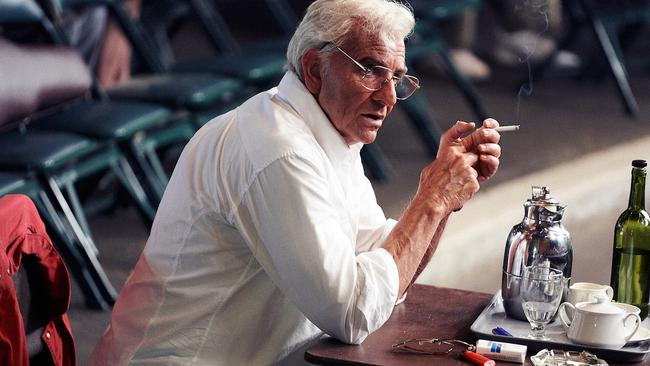

In Maestro, Bradley Cooper is the Jewish American conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein. This is a film you’ll think about long after the credits roll.

Maestro (M)

In Cinemas

★★★★

Let’s lead with the nose. In Maestro, star, co-writer and director Bradley Cooper is the Jewish American conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein, who wrote the music for West Side Story, 1957 play and 1961 film, and Elia Kazan’s 1954 Marlon Brando crime drama On the Waterfront, among scores of other scores.

Bernstein (1918-1990), the son of Jewish-Ukrainian immigrants, had a sizeable snoz. Cooper decided to enhance his own not-insignificant snout with a prosthetic proboscis. For this the filmmaker, who is not Jewish, was branded anti-Semitic. Other critics went as far as to call it the equivalent of Black Face.

I disagree. The nose is not a grotesque hooked beak, as it has been in some of Shakespeare’s Shylocks, a fictional and often caricatured Jewish character. It looks like – heaven forbid – Bernstein’s nose, as his three children have noted. “We’re certain our dad would have been fine with it,’’ they said in a statement put out in response to the outcry.

Nicole Kidman was ridiculed for her Oscar-winning nose in The Hours (2002), but the criticism was more about her performance as Virginia Woolf, a noted anti-Semite by the by, than her make-up.

I can’t remember Gerard Depardieu being challenged to a duel for hotting up his honker in the 1990 film adaptation of Cyrano de Bergerac. And as it happens, it’s that 1897 French play, by Edmond Rostand, that goes to what Maestro, an unconventional warts and all biopic, is all about.

Act 1, Scene 4, Cyrano: ‘‘Tis well known, a big nose is indicative/ Of a soul affable, and kind, and courteous … ”

Was Bernstein an affable soul? His wife Felicia Montealegre (an outstanding Carey Mulligan), a Costa Rican-Chilean actor, knows the answer.

In the standout scene of this 129-minute movie, she confronts her husband in their Manhattan apartment as the Thanksgiving parade passes below. A large Snoopy balloon almost blocks out the sun. She tells him his is angry, arrogant, narcissistic and full of hubris. When he is in a room there is no space for anyone else.

It’s an Oscar-worthy moment that goes to the troubled heart of this film, which has the full support of Bernstein’s children. It’s not about his spectacular public career but his hidden private life as, first, a closeted gay man; second, a depressive; and third, as his wife says, someone who drains all the oxygen from the room.

We do see Bernstein in full flight as a conductor, and here Cooper captures the agony and ecstasy of a man who lived for music.

Cinematographer Matthew Libatique, who received an Oscar nomination for Cooper’s 2018 directorial debut, A Star is Born, deserves to be in the running in 2024.

Bernstein’s music is used throughout to dramatic effect The prologue from West Side Story is particularly well-placed. And we should mention the creator of the nose: Japanese-American make-up artist Kazu Hiro, who has Oscars to his name for transforming Gary Oldman into Winston Churchill in Darkest Hour (2017) and for his work on Bombshell (2019).

Cooper has taken several risks with this film, which he asked to direct after Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg expressed interest but moved onto other jobs. Scorsese and Spielberg remain as producers, so their big shoes were in the vicinity as the film came to be.

The true centre of this film is not Bernstein but his wife, a woman who understands who he is from the start but loves him all the same.

“I know exactly who you are,’’ she says early in their romance, when his main squeeze is the clarinetist David Oppenheim (Matt Bomer). “Let’s give it a whirl.” Not long after, she sees him messing about with a handsome young man and tells him, “Fix your hair, you’re getting sloppy.”

A bit later: “If you’re not careful, you’re going to die a lonely old queen.” Later still she watches him conduct Mahler’s Symphony No.2 like a man possessed and is transfixed by deep love. And that almost unexplainable love is returned. It is an amazing scene. Duality is central to their lives.

The first third of the film is shot in black and white. It has the deliberate look of a 1940s or 1950s Hollywood film in which a couple interrogate and excite each other with sharp dialogue (co-writer Josh Singer won an Oscar for the 2015 film Spotlight).

It doesn’t feel quite real and that’s the intent. From the beginning, Lenny and Felicia are living under a veneer, a thin slice of external

deception covering the inner reality. “Don’t you dare tell her the truth,’’ Felicia tells her husband. “Her” is one of their daughters.

The switch to colour takes the couple into the 60s and 70s. Everything is bursting with life – it’s a cocktail, for Bernstein at least, of cocaine, dance, young men and music, music, music – until someone’s life is put at risk. Here, Mulligan’s performance is heartbreaking.

This is by no means an ordinary film. The nonlinear structure means it comes to us as a sequence of sketches, an almost random collection of scenes from a life.

There may be times where you ask, “What’s it all about?” I did.

The answer is in the pre-titles on-screen quote from Bernstein himself: “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them.”

This is a film you will think about long after the credits roll.

-

Silent Night (MA15+)

In cinemas

★★★

The revenge thriller Silent Night is John Woo’s first American film since the sci-fi drama Paycheck in 2003. This comeback movie has a lot of what Woo is famous for, such as operatic gunfights, but it also has something new: there is almost no dialogue over the 104-minute run-time.

This poses a challenge to the two leads: Joel Kinnaman and Catalina Sandino Moreno. They try hard but in the end fall short. It’s hard to express a character’s full emotional range with a shake or nod of the head, and these characters have a lot to be emotional about.

The action opens with one of the best scenes in the film. A man (Kinnaman) is running through the streets. He’s wearing a Rudolph the red-nose reindeer jumper. A sleigh bell around his neck dings. He breathes hard. His hands are covered in blood. In the near distance there’s gunshots and police sirens. We don’t know who he is or what he’s doing. He’s filmed in slow-motion so it’s an elongated tension of the unknown. He comes to rival drug gangs chasing each other in cars, shooting wildly. He runs into the melee. Why on earth would any sane person do that? One of the gangsters shoots him in the throat.

Cut to a hospital. The man is wheeled into surgery with the Christmas song Silent Night tinkling from the loudspeakers. It’s a fair bet nothing will be calm or quiet from here on in.

We learn his name is Brian. He lives in Texas with his wife Saya (Moreno). He ran after the gangsters and into the shootout because minutes earlier their eight-year-old son was killed by a stray bullet. It was Christmas Eve and the boy’s wrapped presents are still under the tree. He recovers but the damage to his throat means he cannot speak. He can hear though, which makes his wife’s silence more cinematic than realistic. He spends a while in one stage of grief – heavy drinking – before moving onto the other stages that have been around since Charles Bronson made Death Wish in 1974.

He muscles up, teaches himself how to fight, with fists, knives and guns, buys an old red Mustang and learns how to drive like Vin Fast & Furious Diesel. He circles Christmas Eve on the calendar and writes Kill Them All. What happens from here is well filmed, especially the action scenes, but far too predictable. It’s good to see Woo, a native of Hong Kong whose credits include Face/Off and Mission: Impossible 2, putting his toe back in Hollywood waters. Perhaps next time he will go out a little deeper.

David Stratton is on leave.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout