Leonard Bernstein’s daughters discuss Bradley Cooper biopic Maestro

As Bradley Cooper’s acclaimed biopic of Leonard Bernstein is released, the conductor’s daughters tell what family life with the charismatic musical genius was like.

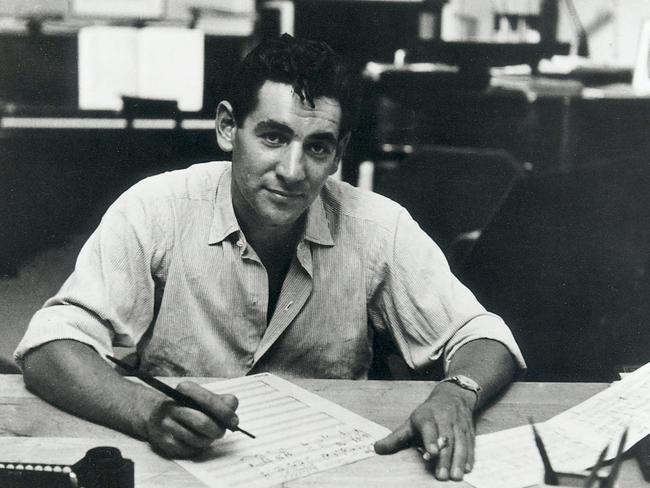

No classical musician made such an impact on public life as Leonard Bernstein did in mid-20th-century America. The son of Jewish Russian immigrants, he could walk into a room full of presidents, movie stars, literary heavyweights and Manhattan billionaires and still be the centre of attention. Or as his daughter Nina Bernstein puts it: “The dazzling figure around whom we all revolved, as if part of his solar system.”

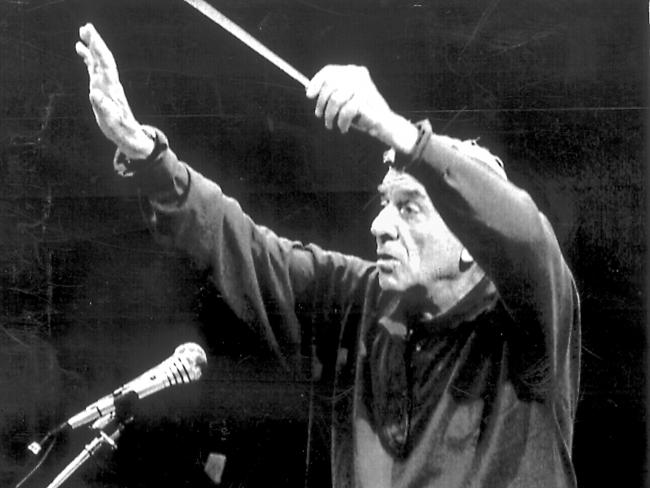

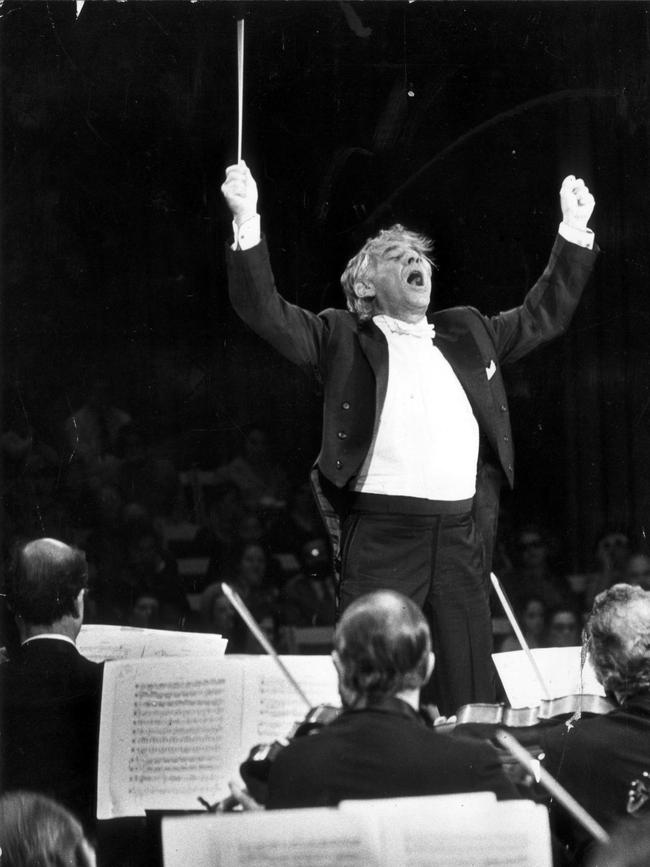

It wasn’t just that his compositions – spanning Broadway musicals such as West Side Story, operas, films, ballets and serious symphonies – defined so many genres of American music, or that his uniquely flamboyant conducting galvanised orchestras into producing performances that seemed to touch the heights of ecstasy and the depths of despair.

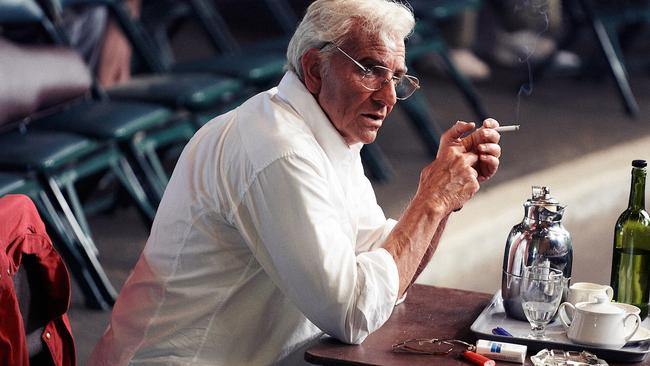

Just as irresistible was his charisma. I met him towards the end of his life (he died in 1990 aged 72), when the furnace was flickering and the decades of booze, pills and 4am bedtimes had clearly taken their toll. Yet for several unforgettable hours he regaled me by quoting whole reams of English poetry by heart, then discussing it with a fluency that left me speechless. That was the Lenny effect.

On top of all that was his sexuality. If his intellect was protean, his fleshy appetites were voracious and all-encompassing. He was married and had three children, but he had gay hook-ups throughout his life. The tension between his family life and his other relationships was never resolved.

Now it’s the subject of a Hollywood biopic: Maestro, directed and co-scripted by Bradley Cooper, who also plays Bernstein – a feat of multitasking Lenny himself might have admired.

Is it actually a biopic? Bernstein’s daughters, Jamie and Nina (71 and 61 respectively), were assiduously consulted by Cooper from the start and are heavily involved in promoting the film. They think it has evolved into something quite different.

“You have to remember this project began 15 years ago, when we imagined it would be more of a traditional biopic,” Jamie says. “At one stage Martin Scorsese was down to direct it. But the years went by and the film wasn’t getting made. Then Bradley came on the team and really transformed the concept. Now it’s not a biopic at all. It’s a portrait of a marriage – very honest, very moving.”

And in places almost painful to watch. Bernstein’s wife, Costa Rican-Chilean actor Felicia Montealegre, knew exactly what she was marrying, as is shown by correspondence between the two, published long after both had died.

In one letter Montealegre writes: “You are a homosexual and may never change – you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depend on a certain sexual pattern, what can you do?”

Nevertheless, as their children grew up and Bernstein deserted Montealegre to live with a gay lover, her anguish became evident. He did return to her, but by then Montealegre was dying of cancer. Bernstein – devastated by grief and guilt – was never the same again.

This is at the heart of Maestro. Consequently the film, despite its title, is as much about Montealegre as Bernstein. That’s fascinating because she gets only passing mentions in most biographies of her husband. “Well, that’s going to end,” Nina responds, “because Carey Mulligan’s portrayal of her is so strong, so gripping, truthful and heartbreaking that people are going to be talking about our mother a lot.”

Presumably she was the one who did most of the parenting while Bernstein was busy being the great maestro? “Yes, Dad was not really involved in domestic logistics,” Jamie says. “He had his own world – his career. It was Mother who would go to our school events or the dentist. I mean, Dad went to the dentist plenty of times, but not with us.”

And this was the era, late 1950s and early ’60s, when women’s lib was still mostly an aspiration. Wives were expected primarily to support their husbands.

“Yes, being Mrs Maestro certainly had a built-in old-fashioned aspect to it,” Jamie says. “Yet my mother was a distinguished actor in her own right – she worked with Boris Karloff, Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner.” Did Bernstein support her in her career? “On the surface maybe, but the subtext was different,” Jamie replies.

“When I was starting my own career as a singer-songwriter he was also encouraging, but the subtext was always ‘I’m the heavyweight in this department’. As a result I always had a feeling of, ‘Who do I think I am, trying to make my own mark?’ Eventually I set that career aside and was relieved that I wasn’t bashing my head against that wall any more. I suspect something similar was going on with my mother.”

On top of that, of course, Montealegre had to cope with Bernstein’s almost non-stop infidelities.

“Our mother suffered a lot,” Nina says. “I was at home at the time because I am quite a bit younger than my brother and sister, so I did witness her upset and felt terribly for her.”

One powerful episode in the film seems to epitomise her anguish. Bernstein rushes in triumphantly, brandishing the manuscript of his just-finished Kaddish Symphony. Montealegre responds by jumping in their swimming pool and submerging herself, as though desperately seeking oblivion or escape. The incident happened in real life, the sisters say – but in a totally different atmosphere.

“When our dad wrote the last notes of the symphony,” Jamie recalls, “he came running across the lawn shouting ‘I’ve finished!’ and my mother shouted ‘hooray!’ and they both jumped in the pool with their clothes on. It was a moment of pure, spontaneous joy.”

So Cooper exercised considerable “director’s licence” in re-creating the scene?

“Oh yes, it’s very much Bradley’s film,” Nina says. “There are things in it we recognise, and liberties taken. But he really tried to achieve a sense of authenticity. What he invented does ring true.”

The family also has endorsed Cooper’s physical portrayal of Bernstein. That extends not only to his uncanny imitation of Bernstein’s conducting gestures (especially in the movie’s musical climax, a stunning reconstruction of the conductor’s celebrated performance of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony in Ely Cathedral), but also to his use of a false nose to represent Bernstein’s prominent conk – a practice denounced by some as “putting on Jewface”. Where do the sisters stand on the great nose question?

“We put out a statement saying how ridiculous the fuss was and that our dad would have been perfectly happy with Bradley’s appearance,” Jamie says.

“The fact is, Bradley went to great lengths to embody our dad in all sort of ways – voice, gestures, everything. The nose was the least of it. I mean, the earlobes were incredibly accurate.”

In one way, however, the film presents a distorted portrait of the maestro. Because it concentrates so much on Bernstein’s private life there is virtually no mention of his public one: his sometimes almost reckless interventions into politics, for instance.

“Oh yes, Dad was political from the very beginning,” Nina confirms. “Even back in the 1930s he was part of what was really an anti-fascist movement. Many artists and performers were. Then of course in the 1950s, when the ‘red scare’ and communist witch-hunting was in full swing, a lot of them got into real trouble.

“Dad was always being watched by the FBI. When he finally got hold of the FBI’s dossier on him, it ran to 800 pages.”

“Yes, he was always involved in something,” Jamie adds. “In 1948 he went to Israel at the height of the Arab-Israeli war (playing an open-air concert in the desert for Israeli troops). Then it was civil rights, then protesting the Vietnam war, then no nukes, then advocating proper care for AIDS patients. If there was some injustice somewhere, he was going to speak out. That was how he was.”

What’s most surprising is the film’s omission of an event that had enormous, and far from positive, repercussions for the Bernstein family. That was a fundraising evening attended by the glitterati of Manhattan, held in the Bernsteins’ Park Avenue apartment in January 1970 for the militant Black Panthers civil rights group. In a long and subsequently famous article for New York magazine, the young journalist Tom Wolfe, who had filched his invitation from someone else’s desk, lampooned what he saw as the absurd political posturing (“radical chic”, as Wolfe called it) of rich arty liberals such as the Bernsteins.

“Tom Wolfe’s essay was wildly unfair,” Jamie says. “For a start, he said it was our dad’s event when it was our mother who was the host. She was also very active in social causes – civil rights, prison reform, the peace movement. And secondly, he characterised it as some sort of superficial society event when in fact it was a serious fundraiser. The result was that both our parents got dragged down.

“Our dad received all this hate mail, and the Jewish Defense League (which had declared the Black Panthers anti-Semitic) picketed our building. It was only decades later, when our dad got hold of his FBI file through the Freedom of Information Act, that he found that the FBI had written all the hate mail and that the pickets were bristling with planted FBI agents.”

Why? “Because the ultimate aim of the FBI was to get Jews and blacks hating each other,” Nina says.

Whatever the intention, the result of this furore – especially the humiliation piled on Montealegre – was to put even more strain on the Bernstein marriage. So why isn’t it in the movie? Why aren’t any of Bernstein’s political activities there? “Well, one movie can’t have everything,” Nina says.

“There was some political stuff in one version of the script,” Jamie adds. “But it’s true that there’s so little time in a movie to tell the story of an enormous life. Many threads had to be omitted.”

What do the Bernstein sisters hope Maestro will achieve? “We hope it will bring new audiences to our father’s music,” Nina replies. Really? Does his music still need championing?

“Absolutely,” Nina adds. “Young people today don’t know who Leonard Bernstein is or why he still matters. We hope a new generation will get infatuated with the music they hear on Maestro. There’s a lot of it.”

And also be emotionally gripped by what is by any standards an astonishing story of marriage, betrayal and reconciliation?

“That’s right,” Nina says. “We find people come to us after the film with tears in their eyes because, even after all that happened, they see that our parents still had such love for each other.”

The Times

Maestro is in cinemas from December 7 and on Netflix from December 20.