The remarkable quality that holds our nation together

For 23 years, as a working journalist, I have been documenting Australians who simply refuse to succumb to whatever pervading darkness threatens to blacken their light. These stories are the keepers.

It is during prolonged periods of acute CRI that I often find myself ducking under my writing desk and digging into an $11 transparent plastic IKEA storage box filled with the newspaper and magazine clippings of all the feature stories I have written for The Australian of which I’m most proud. These stories are the keepers. The ones that stayed with me. Stories of great Australians and famous Australians and ordinary unknown Australians who deserved so much more than fate allowed. Only recently did I discover, while piling endless articles from the box onto my lap, that all these pieces are linked by a common thread; one single theme rippling through every real-life narrative, passing across time and place, from feature to feature. I kept identifying the same remarkable and infectious human quality. One beautiful word kept bouncing between the colour portrait photographs of all these glorious persons of journalistic interest. From Betty Cuthbert to Mick Fanning. From Grantham flood victims to Black Summer bushfire survivors. One perfect word reverberating triumphantly between the gaps in all that press ink.

Resilience.

Time and again, it seemed, I left my desk in the Brisbane bureau of The Australian in Bowen Hills and set off into some corner of the country in search of resilience. I realise now that I have been obsessed with the stuff for most of my adult life. For 23 years, as a working journalist, I have been documenting Australians who simply refuse to succumb to whatever pervading darkness threatens to blacken their light.

These journalistic endeavours, I assure you, have transformed my life. They have shaped me as a father, a husband, a brother, a son and a man. I have no doubt this obsession is rooted in my need to make sense of the ways in which, through much of the 1980s and 1990s, I watched someone I love very much – my mum – overcome everything from drug addiction to imprisonment to domestic abuse drawing on nothing, from what I could observe, beyond a particularly Australian kind of in-built human resilience.

We are a nation of scrappers. We have been blessed with enormous resources of coal, gold, iron ore, nickel and pluck. Emotional minerals. True grit. Real salts. We have the mongrel underdog in us. For Australia is an underdog story. Australia is a resilience story. It is a 60,000-year-old story of a First Nations people who adapted and thrived in a 7.7 million square kilometre frying pan dotted with eucalypts. It is the story of a fleet of British thieves and hustlers and ne’er-do-wells sent to a saltwater prison in an unknown south, in quite possibly the most audacious, obnoxious and pitiless social relocation experiment in human history. Who could possibly imagine a place more bitterly and cynically formed in the gutter and at once so giddily and profoundly intent on looking up at the stars? Modern Australia is a 250-year-old multicultural story of ordinary men and women turning nothing into something. Towns from tents. Cities from dirt. Hope from despair. Light from dark.

Here’s a newspaper feature about floods in Grantham, south-east Queensland. I’ve spent countless hours knocking on doors in towns and cities across Australia ravaged by fire and flood. It’s the newspaper feature writer’s job to come in and try to make sense of the devastation. Find some meaning in all the rotten, sometimes irreversible, climatic happenstance. Not uncommon to find yourself asking questions of people standing in doorways of mud-caked and ruined homes, scratching their heads and wondering why God’s dice rolled down their street. Not uncommon to find those same people turning to spot some miraculously untouched corner of the house where the water didn’t reach and uttering something soft and utterly resilient: “Well, at least we saved Gran’s recipe book.”

I remember a bloke crawling around an upside-down caravan in a flood-ravaged Goodna caravan park, south-west of Brisbane; summer 2011. The caravan was literally covered in toxic human shit and I’ve seen few smiles as wide as the one this man offered when he found an unbroken bottle of XXXX Gold in his half-sized upturned Kelvinator. Whatever gets you through the night. Whatever gets you through the nightmare. I remember interviewing Lockyer Valley disaster victims during the floods of January 2013 who had only just repaired their homes from the floods of January 2011. I watched their faces turn from darkness to light as they shrugged their shoulders, houseless and broken, and found silver linings in the most absurd truths: “Well, at least it’s not as bad as last time.” That was invariably when some misguided and young media person standing in the main street of Grantham, battling a bad case of intrarectalcranialitis, would whisper something out of their rear end such as, “Why the f..k didn’t they move?”

Why? Because they had nowhere else to go. Because they were penniless. Because they were screwed by God and their chosen insurer. And because they were resilient.

Courage is a quality we have built a national identity upon. Battlefield heroics and sacrifices. Sporting glories. Our collective resilience should be no less celebrated or unifying. Resilience ripples daily through every office space, every factory floor, every suburban street across the country where yet another glorious and indefatigable Australian worker is waking at dawn to march off to the job they’ve hated for 25 years on account of its hamster-wheel drudgery and mundanity. But that’s all OK because Jenny really, really loved the white Nike Air Force shoes with the thick soles that she got for her 16th birthday. That kind of unheralded national resilience makes this shimmering island tick. It’s just not so easy to capture such resilience in bronze.

Here’s a man named Wazza Shaw in a piece I wrote about the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20. I will remember Wazza Shaw’s light for the rest of my days. Wazza lived in Mogo on the NSW south coast. I knocked on his door with a single question: “What the hell did you just live through?”

“The apocalypse,” Wazza said. A father of two. Mullet haircut. Wazza got his family to safety then returned to his Mogo street where he fought a raging kilometre-long firefront with a makeshift fire hose that he ran from a generator fixed to the back tray of his ute. After he saved his house, he put his life in profound danger to save the homes of his neighbours. Terrifyingly and unmistakably alone, he drove up and down his abandoned street wetting down houses as the fire lashed and spat, eventually surrounding him with zero exit points. Plan A: keep wetting the houses until the fire swept out of Mogo. Plan B: lift the iron grate in the gutter on the street and slide into the stormwater drain and pray that a bloke don’t suffocate. “Thank f..k I never had to go to plan B,” he said. His brain told him he was dead. His busy head was certain of it. But his heart told him something else. His heart said there was hope. And that was the theme of that endless summer. All that light from the dark. All that quintessentially Australian resilience.

I remember the resilience of the land that summer. I called it “resilience green”. That rare and inspiring emerald colour that started to pop from black burnt matchstick forests. New growth. New life. I described it as a green so ancient and true that it made roadside kids giggle with wonder at the sight of it. Hope green. Resilience green.

Kerry Shepherd. Her warm, welcoming face in a portrait for a story in The Weekend Australian Magazine we headlined “Love and Fate”.

Kerry has become a dear friend. I wrote a story in 2013 about the day Kerry lost her beloved husband, Chris Walton. He was crushed by a Burleigh Heads shopfront awning that randomly collapsed above him, two days before Christmas in 2012. Chris’s final act before he died was to push two children to safety. I could write a novel detailing the depths of Kerry Shepherd’s resilience. But I’m thinking, here and now, about Kerry and Chris’s son, Fin, who was only 13 when his dad died. It was Fin who got his mum through the grief of his father’s death. Kerry calls him a revelation. “As long as the wheels were turning, as long as he had normality – and an incredible friendship group – he was handling it,” Kerry later told me.

Fin and I caught up recently for a beer at a brewhouse he liked in Brisbane. He had just returned from a trip through the United States and Canada with two dear friends. Fin’s a rock climber. Nothing but peace and pain to be found on the face of a granite monolith. Fin spent half an hour detailing a life-changing climb he completed, scaling the mighty El Capitan, a vertical rock formation rising 914m out of Yosemite National Park. There is a light in this beautiful young Australian that will never go out and I’ve been wondering lately if his light is a byproduct of tragedy. Resilience as an equal and opposite reaction to sorrow. Training got Fin up that El Cap rock face, of course. Rock smarts got him up there, too. But I knew there had to be something else. “Was your dad with you?” I asked. And he shook his head in the way young men do when they’re in complete agreement with something. “Of course he was,” Fin said.

Irene Tchaikovsky. I spent a night on the street with Irene. I was writing about homelessness in Australia. Irene was 70 years old and slept regularly in a bus stop on Adelaide Street, Brisbane. Her possessions were one towel, seven shirts, one dress, five pairs of underpants, a dressing gown and a pencil case filled with a toothbrush and seven lipsticks. “What keeps you going, Irene?” I asked. She thought about this for a moment. “Hagar the Horrible,” she said. Every night when Irene briefly gave her mind over to thoughts of packing it all in – ending the grinding 24-7 struggle to find shelter, food, clothing, dignity – she thought about missing out on reading the next morning’s Hagar the Horrible cartoon in The Courier-Mail, and that was a fate she was resolutely, resiliently, unwilling to accept.

Here’s a piece I wrote on the great Betty Cuthbert as she was nearing the end of her life. Here she is in a wheelchair. Always something narratively meaningful about our beloved Golden Girl – a four-time Olympic sprint champion – incapable of using her wondrous legs. As if the mid-century sporting peaks weren’t breathtaking enough in Betty’s story. Then you come to the part where she lived with multiple sclerosis for almost half a century, tirelessly campaigning for MS research and disability awareness, before she died in 2017.

Here’s a piece on Mick Fanning. You want to know something about an Australian’s capacity to fight back? This guy fought back against a shark. Of course, the great truth about Mick’s unbreakable resilience is that he fought all his toughest battles long before he encountered that great white in the waters of Jeffreys Bay, South Africa. He’s the son of a working-single-mum-battler-nurse who raised five children on her own. When he was 17, he lost his beloved brother, Sean, in a car accident. Mick locked himself in his bedroom and refused to leave it for a week. When he finally did, he had a powerful and private notion swirling through his head: to honour his brother by becoming a world champion surfer. That foolish shark didn’t stand a chance.

I keep flipping through the articles. On and on it goes. Endless Australians who steel and stir my soul, just by living, just by working.

Geoff Beattie. The south-east Queensland dairy farmer who fell into a deep depression when he lost his wife, Elaine, to leukaemia. This happened around the same time the Australian dairy industry went south, along with Geoff’s livelihood. He hit the bottle. The hard stuff. Whiskies and brandies. All the stuff Elaine used to pour into her country fruitcakes. Then one day his young kids said they were worried about him. And something clicked in Geoff overnight. Instead of slamming whisky down his gullet, he poured the whisky into a fruitcake mix. Light from the dark.

Today, Geoff Beattie is an icon of the Royal Queensland Show, and one of the most decorated country cake makers in Australia. Resilience is a key ingredient in his famous recipes. The stuff is whisked deep into every cake mix he slides into an oven. And so is his love for Elaine. Because love and resilience are, I realise, so often connected.

If you’ll permit me a moment of shameless CRI, I want to briefly consider the notion that resilience is formed from love. So often do we Australians carry on in the memory of someone we’ve lost, or in the name of someone we love. What if it’s actually love that’s been keeping this whole wild and shimmering island moving forward for all these years? I never really had to do 23 years of journalism to work out why my own mum kept standing up, moving forward, carrying on through her darkest hours. I’ve always known it was love. Love of her four sons. Love of me.

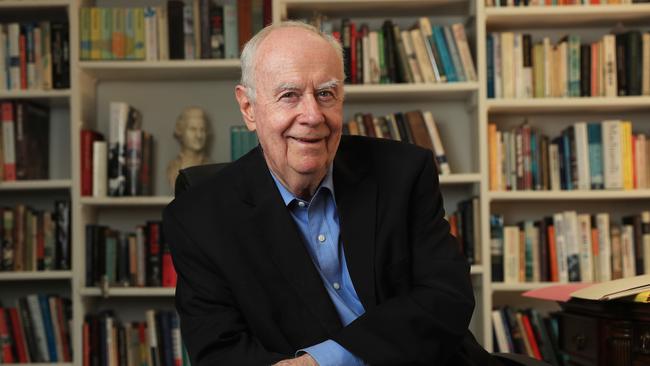

And then I come to the most resilient man I know. Paul Stanley. I owe him a phone call. Been too long between chats. I’m holding his picture in my hands. A Weekend Australian Magazine piece straplined, “The Fight That Never Ends”. Eyes downcast in the magazine portrait photograph. Scruffy snow-coloured hair. Wrinkles of time across his face. Wrinkles of grief.

I remember the first time I went to Paul Stanley’s house in east Brisbane to interview him about the death of his 15-year-old son, Matthew, who was killed by a king hit – a coward punch, as it would become known – at an 18th birthday party in 2006. Paul was in the early stages of creating the Matthew Stanley Foundation, which would go on to transform Queensland’s awareness and response to youth party violence. Light from the dark.

We must have spoken for four hours. Much of that time I spent in silence as I waited for Paul to recover from the body-buckling, tear-streaming, spit-lipped grief of “losing Matty”, the headline we used for that early story. I will never forget the way he walked me out to my car after our chat. Sunset in the suburbs. Birds whistling. He asked me, in the interests of filling a silent space with small talk, how the rest of my week was shaping up. And I told him that my wife was scheduled to give birth to our daughter in the Mater Hospital. In a matter of days, I explained, I was going to become a dad. And Paul threw his head back and laughed. When he looked back at me I could see there were tears in his eyes. I swear to you now they were tears of joy. This man, who had just spent four brutally honest hours talking about the tragic loss of his son, had somehow dug deep inside himself to find the resilience – and the love – to find joy inside a quiet suburban moment between two men standing beside the same Toyota hatchback that I drove my daughter home in three days later. “You will never do anything more beautiful in your life,” Paul said.

Hard to lose your head up your own backside when you are reminded of words like that from people like Paul Stanley. Physically impossible, in fact.

I decide to give Paul a call on his mobile. He doesn’t pick up so I send him a text. I tell him what day it is today. It’s my daughter’s 17th birthday. Kid just had her school formal. Two days ago she was singing until she lost her voice with 96,000 friends at the Taylor Swift concert. “You once told me being a dad would be the most beautiful thing I’d ever do,” I tap with my right thumb. “Just wanted you to know, you were right. Love you mate. Trent.”

Big Ideas

The stories Trent Dalton is most proud of

For 23 years, as a working journalist, I have been documenting Australians who simply refuse to succumb to whatever pervading darkness threatens to blacken their light. These stories are the keepers.

The trendy disparagement of science is un-Australian

Richard Scolyer and Georgina Long faced the worst possible scenario when Richard was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. The melanoma researchers fell back on their medical knowledge to make a brave decision.

The turning point for all strong women? It’s not motherhood

It’s the pain and confusion that is my strongest memory of the worst year in the lives of all women, I’m sure. It was my first insight into the complexity and competition of womanhood.

The balance is broken: What now for democracy?

Radical shifts in social order; technologies that shape as foe rather than friend; erosion of faith; an end to truth and facts. The strength of our good society is about to be put to the test.

‘No one is disadvantaged just because they are Indigenous’

No meaningful change comes from selling ourselves short through guilt politics. It comes from understanding our history in its entirety.

Ideas are the source of all power in human affairs

Political power may grow out of the barrel of a gun but it is an idea that compels someone to pull the trigger, to raise an army, to start a war.

There is no choice: a Holocaust survivor’s view of courage

A difficult choice is speaking out against the populist but morally reprehensible behaviour of the crowd. If the tipping point between democracy and anarchy is to be avoided, we, you and I, need the courage to fight for our democracy.

What 1184 days’ jail has taught me about liberty

The Australian journalist who was detained for more than three years in China reflects on the true value of freedom.

60 most influential people of the past six decades

To celebrate The Australian’s 60th anniversary, this masthead has brought together a list of those who have had an impact on all our lives.

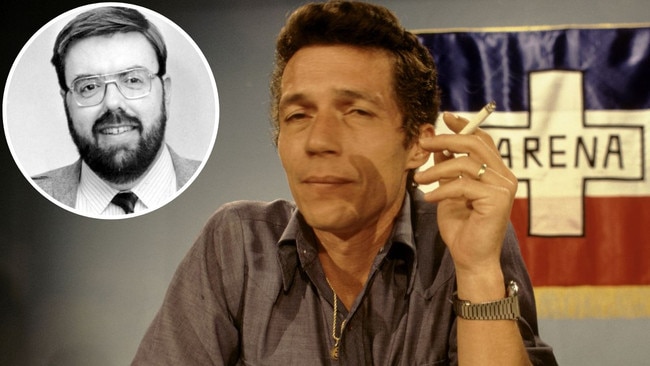

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

Intrarectalcranialitis. The scientific term for having one’s head unmistakably stuck up one’s backside. Otherwise known as “cranial rectal inversion” or “CRI” for short. I’ve endured a few suffocating bouts in my time. This inherently anti-social condition is thankfully one of only a few real dangers – eye strain, finger lock, gin lust – facing the full-time contemporary Australian writer. My wife, mercifully, can spot symptoms early: excessive criticism of the Qantas Club breakfast menu or finishing sentences with, “… and that’s why I never read Foucault after 9pm”.