‘Terrible things happen to homeless women at night’: Inside Brisbane’s 3rd Space drop-in centre

Nobody tells you about the weeping footsores. Or the heatstroke. Or the musculoskeletal disorders. Homeless women in particular dare not speak of what happens to them after dark. But they do tell Brendan Clark.

The blister-lipped, ruby-eyed, pride-donged night walker reminds me of my dead dad. Every piece of him is thin except his belly. He sifts through a Glad Bag of half-sucked cigarette dumpers, lights one up, waits for the 3rd Space homeless drop-in centre on Brunswick Street, Fortitude Valley, to open for breakfast. Same kind of thick sheepskin winter coat my dad wore when we’d go camping near the wrecks on Moreton Island. My dad used to drag on durries just like that when his beer-soaked head was sore in the morning; eyes closed to the judgmental sun. Not the worst way to process the magnitude of a national housing crisis and the more than 120,000 Australians who sleep rough each night in the lucky country. Personalise it. Bring it home. Witness a social emergency through the lens of the ones you love the most.

Doors are open now and this man and I meet shoulder-to-shoulder at the brick entry steps used by roughly 80 homeless and at-risk Brisbane locals every day.

“You go first,” I say.

“No, you go first,” he insists.

The last shall be first and the first shall be last this morning. The meek shall inherit the porridge. Outside of the hospitals and schools, I’d call 3rd Space the most essential building in Brisbane. Four stories of old brown brick. Red corrugated iron roof. A stone’s throw from Philip Bacon Galleries where, last year, William Dobell’s Chrysanthemums went on sale for $150,000 – or the equivalent of 30,000 serves of 3rd Space’s famous $5 bacon and eggs. The soup and porridge are free. Three pieces of toast will cost that man in the winter coat 60 cents.

A high school teacher named Jane takes her eggs sunny side up and shuffles to a booth in the dining hall that looks out to the smoker’s courtyard. She’s one of the 54,000 homeless women in Australia. Jane has been sleeping in the grounds of a Brisbane CBD cathedral. She doesn’t eat well alone. Strangest thing. The anxiety builds in solitude and the food gets tough to swallow. She comes to the 3rd Space café to be around people. Human connection helps keep her food down.

Jane was raised in Melbourne; taught in high schools there before moving to Queensland 12 years ago. Her last teaching job was at Aspley High School, on Brisbane’s northern fringe. She quit during a peak Covid-19 outbreak. She says the job got too much for her. Life got too much for her. She struggled to pay the rent. “I was already down and then I had this thought,” she says, raising her right forefinger, eyes alight as though an apple just dropped on her head. “I’m gonna hit the streets! I told myself I was gonna start all over again. Start from nothing. That’s what I did. Started sleeping in churches.”

“What does it feel like?” I ask.

“What does what feel like?” she asks.

“Sleeping in churches.”

“It’s scary,” she says, slicing through a buttered piece of toast. “It’s horrible. It’s cold. Between 2am and 5am, no matter what season it is, it’s cold. You feel hopeless. Not being able to wash. Not being able to feel human, that’s the worst bit. Then there’s the spiders.”

“The spiders?”

“I once got bitten by a white-tailed spider while sleeping rough,” she says. “Nobody tells you about the spiders.”

Nobody tells you about the weeping foot sores from all the walking. Nobody tells you about the nail fungus. Or the heatstroke. Or the musculoskeletal disorders. The compromised immune systems. The respiratory diseases. Nobody tells you about the things everybody tells Brendan Clark. He’s the centre’s concierge. He’s the man with the office by the front door.

“There is theft and robbery every night,” Brendan says. “There are groups that go round and steal off the homeless in their sleep. That’s where we’re at. That happens every night in Brisbane in 2023. And there’s worse things that happen to the females. Terrible things that go unreported to police. The women come in here the morning after and tell us, but they don’t want to tell police because they’re told that they’ll get it 10 times worse if they do report it. They’re scared because they know they’ve gotta go back the next night to the same spot on the same street. They don’t have anywhere to hide from those people. In their words, ‘We just have to put up with it’.”

He points to a darkened corner of the centre running off the screened sign-in desk where several homeless women are sleeping in single day beds.

-

“A lot of them stay awake during the night on purpose because they know if they fall asleep they are very vulnerable,” Brendan says.

-

“They come here in the morning and go straight to our day beds and have a sleep.”

It’s Brendan’s job to keep the centre safe, to keep the peace. He resolves conflicts, extinguishes the spot-fires of violence that flare up often in the dining hall. His greatest tool is empathy, witnessing a social emergency through the lens of the ones he loves the most. He gets to know the regulars. He tries to understand their trigger points. Every hallway chat is another case note to help build extremely nuanced conflict resolution strategies, tailored to each individual regular. Some will walk through the 3rd Space entry door some 40 times before they even say hello to Brendan. Some will tell him their life story within 40 seconds. “Their moods change,” he says. “Every day, we go up and down with our visitors. Not knowing where your next meal is going to come from, that’s very stressful. Now we’re seeing people who never had to come here before. We’re seeing more families. Single mums with kids. Every week. Single fathers with kids, every week. They have nowhere else to go. Life has dealt them a bad turn out there. And they’ve been told to come to us. We can only help them as much as we can.”

Brendan tells me he grew up in Bracken Ridge, on Brisbane’s northern fringe. He knows the Bracken Ridge street where I grew up in a red brick public housing shoebox. My dad and his four sons rented that house for a decade for less than $100 a week. Brendan strongly doubts that home would be available to my dad were he raising his boys in 2023. One floor above us, next to the visitors’ internet and art space, is a family area for parents and kids. There are toys and books and desks for kids to do their homework on. More than 17,600 Australian children under the age of 12 are homeless. The family tents have returned to Musgrave Park, a long-time space for Brisbane’s homeless and disadvantaged. There are children doing maths equations inside cars parked overnight in well-lit shopping complexes and petrol station carparks across the city. Lesson number 36 in the guide to sleeping rough: always choose a spot beneath artificial light. Lesson number 37: nobody robs you on CCTV.

3rd Space has a dedicated family support worker whose primary aim is to keep Brisbane children with their families and in school, and out of the complex and potentially destructive child protection system. “Years of neglect by governments has led to the situation where we just don’t have the housing available,” says 3rd Space CEO Lesley Leece. “It’s just not there. Then inflation bites hard and suddenly we’re seeing increasing numbers of families who have never been in the situation before where they need to come in and say, ‘I can’t feed my family and I can’t pay the rent’.”

Regulars call Lesley’s basement office “the bunker”. She likes being down here. She feels it’s right that the good offices with the natural light upstairs should go to the support workers finding homes for visitors; the psychologists bringing clients back from the edge of suicide; the indigenous health workers, the centre GPs, the nurses, the podiatrists, the visiting lawyers, the disability carers and registered NDIS providers. Lesley runs a team of 20 paid staff and 120 volunteers, such as the two sisters who have worked the reception desk one day a week for almost two decades.

Lesley walks me through the donations room down the hall from her office. A vast space of shelved and labelled plastic storage boxes. “Men’s bottoms for sorting.” “Bags and backpacks.” “Crop tops size 14.” “Women’s bras size 16.” Beanies and knitwear. Boxes of in-flight potato chips and biscuits donated by airlines. Sanitary pads. Coats and ponchos and running shoes. Everybody wears running shoes on the street. We pass the centre shower and toilet block. We pass the centre notice board filled with health flyers and fundraising events.

“What’s this one?” Lesley says, smiling wryly, pointing at a newspaper article someone has fixed to the notice board. The article is about a fundraising event I’m doing for Brisbane’s Second Chance Program – a not-for-profit dedicated to combating the rise of women’s homelessness – coinciding with the launch of my latest novel, Lola in the Mirror. The book was inspired by the 15 years I’ve been writing magazine feature pieces about 3rd Space.

Whole characters were constructed based on people I’ve met in these rooms and halls. The book’s about a 17-year-old girl and her mum on the run from a man they left behind in a kitchen 16 years ago with a paring knife in his Adam’s apple. That sentence alone could be traced back to the three generations of women from the same family – grandmother, mother, pre-teen daughter – who I interviewed 10 years ago at 3rd Space, then known as 139 Club, the name it was founded with in 1975. It was so heartbreaking – three generations of women forced to eat in a homeless shelter, still reeling from the impact of domestic abuse – that I strongly considered not filing that story in the first place.

The mum and the daughter in Lola in the Mirror have fallen through the cracks of urban Australia and found themselves a home – a family – in a community sleeping rough by the Brisbane River. It’s a crime story. It’s a mystery novel. It’s a love story. It’s a story about that intimate and deeply confronting thing we do every day when we look at ourselves in the mirror. The 17-year-old girl in the story doesn’t know her name because names are dangerous for girls on the run. With no identity to speak of – no sense of self or place in the world – the girl has come to believe she is, quite literally, invisible to the people who pass her in the street. Invisibility, of course, has its bonuses. But it also has its burdens. “You ever tried to get some identification without some identification?” the girl asks in the book. “It’s like trying to go to sleep with your eyes open.”

“Interesting that you mention identification,” Lesley says. “We had a program that was funded by Brisbane City Council for three years where we had a worker who was specifically dedicated to getting people their ID. So many people who come here don’t have ID. You can’t get housing, you can’t find employment, you can’t get anything in this world without ID. The program wasn’t just about getting that physical birth certificate. It was very much about helping people negotiate the system because they can’t always do that for themselves.”

I’m momentarily confused by Lesley’s words.

“That program sounds utterly essential,” I say. “Why did it stop?”

“We lost the funding,” Lesley says. “I’ve tried hard to get that funding from other sources. Haven’t been successful yet. I’ll keep trying.”

We amble back toward the centre kitchen where head chef Andy Lincoln and his team of kitchen volunteers serve almost 3,500 free and heavily discounted meals every month. Andy’s been doing it for five years. That’s close to 210,000 meals all up. “Lotta meals, Andy,” I say.

“Lotta need,” he says.

Change begins with breakfast. The eggs and bacon will get the regulars through the door. With a full stomach and a cup of warm coffee in their hand they are more likely to then engage with the services upstairs. They’re more likely to do that eye test with the visiting optometrist. They’re more likely to sit down with the member of Services Australia who has a permanent desk in the centre as part of a pilot program that Lesley says is transforming the way regulars are engaging with essential government services.

“Hey, here’s Mario,” Andy says, pointing at an elderly regular dressed in a European football jersey.

“My full name is Mario Milano Spaghettio Macaronio Bologneseo.”

“I take it you’re Italian, Mario?” I say.

“No,” he says, insulted. “I’m from Germany.”

Mario points at Andy the chef. “I have been coming here for 20 years,” he says. “If Andy ever leaves this place then I’m leaving, too. But I don’t want to leave because… because…” A thought seems to hit him like a lightning strike. He points to the front entry of the centre. “Because there are people who are in trouble out there,” he urges. He holds out his hand to me: “Now, let’s share a little Covid-19.”

“Missster Dalton!” another man hollers above a plate of bacon and eggs behind me.

“Norm!” I holler.

Norman Long featured in a book of non-fiction short stories I wrote in 2011 called Detours. The book was the sum product of asking some 20 regulars at 3rd Space to tell me about the specific moment – the detour – that first set them on the path to homelessness. Drugs and drink will keep a person on the street but won’t always put them there. Far more often than not, I discovered, a person’s detour was a moment of trauma; a moment of tragic misfortune; a moment of insurmountable despair. We are, any of us, but three wrong detours from the gutter. Maybe only two detours in 2023. The book hardly set the literary world aflame, but whatever money was made from book sales went back to the 20 people featured in its pages.

“Remember the book launch?” Norm asks.

Former Queensland Governor Penelope Wensley launched the book in the heart of the Fortitude Valley mall. “I remember it vividly, Norm,” I say. “You spoke beautifully.” Norm spoke about the fact that he carried a stutter for almost 20 years, and it caused him to become what he called a “social recluse”.

This is what he said: “At the age of 22, I had a clerical council job at City Hall. A girl who worked with me in the office took an interest in this stuttering boy. I asked her out because I had a car. I took her to a drive-in movie theatre and that night I had my first sexual experience. I came to work the next day so very confident that people almost laughed at me. I never stuttered again. I can’t comprehend how I overcame the stutter in one night, but I did. I married a good woman at the age of 28 but we got to a point of fallout. The marriage broke up. It was the pressure of life. It broke me, emotionally. I moved into a unit, but I found it difficult to live on my own. No one knew me. Nobody knocked on my door. Nobody phoned. I got very sick. It was impossible to work. I understood I was psychiatrically sick, being so lonely. I spent three months in a homeless shelter. But I made friends on the street. And the friends I met on the street made my life worth living.”

Norm landed a room in a New Farm boarding house in 2005. Today, he lives in Enoggera in a unit he found with the help of Bric Housing, an essential affordable housing service for South-east Queensland’s disadvantaged.

“I was the fifth person to speak at the launch,” Norm recalls, proudly. “I didn’t do too badly. I met Penelope Wensley that night. I told her you were my friend and I told her how important a friend is. It’s very common for homeless people to not have many friends. But I made friends that night.” Norm leans over his breakfast plate and whispers something to me. “I have a philosophy that keeps me going,” he says. “Go and smell the rose, Missster Trent Dalton. Go and smell the sweet fragrant rose.”

Lesley follows Norm’s advice and moves through a set of swinging glass doors from the dining hall into an outdoor smoking courtyard connected to a place called the Hope Garden, a memorial space dedicated to all the regulars who have died inside the cycle of homelessness. I ask Lesley about what happened to the memorial plaques that once lined the courtyard’s wall. “It got to the point where we just couldn’t keep up with all those who had passed away and people were coming in saying, ‘But you don’t have my best friend up there?’” she says.

And this might be the saddest thing I’ve seen inside this shelter across 15 years of visiting it. The truth hurts. It gets me in the bottom of my half-full belly. Nothing got better after 2008. Everything got worse. The public housing plans couldn’t keep pace with the houseless. The job creation plans couldn’t keep pace with the jobless. The memorial wall couldn’t keep pace with the dead. “We replaced the individual plaques with a memorial garden to remember every person we lose,” Lesley says.

The garden was paid for through a bequest from a regular named Dan Hope, who died two years ago, not long before his 40th birthday. Dan’s mother Margaret, who was instrumental in establishing the garden, would join her son for a coffee in 3rd Space almost every day.

“This is a place where you can stop moving for a second,” says centre regular Damo. “You snooze you lose on the street. But this is a place to get some solace.”

Scott Mulhern, 57, rolls a cigarette by the Hope Garden. He’s a military veteran living on a disability pension. “Mental illness,” he shrugs, lighting his smoke. “Schizophrenia.” He wears a T-shirt that reads: I can only please one person a day and today is not your day. Tomorrow’s not looking too bloody good either. He hasn’t been homeless for 10 years but he visits 3rd Space for the services, the food and the friendships. “It’s never been worse out there,” he says. “Finding a place that’s affordable on a pension like mine, the places are all infested with rats, and the ones that aren’t you have to get three or four people sleeping in the place to help share the cost.

-

“There’s people on $100,000 a year having trouble keeping a roof over their head. How’s someone on a pension gonna cope?”

-

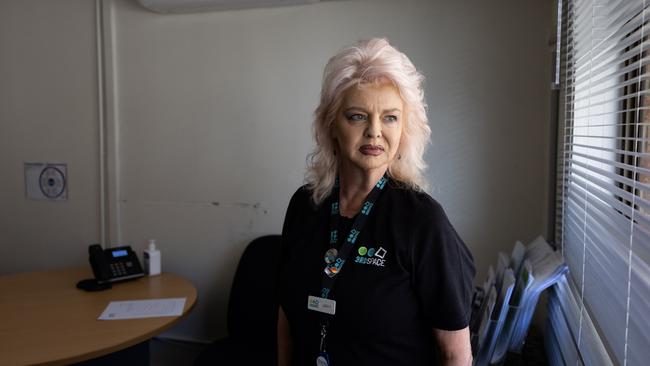

In the services office on the uppermost floor of the centre, Linda Wilson-Marks is typing a recommendation-for-housing letter to Micah Projects – an extremely successful and essential housing support and advocacy service – on behalf of Jane, the high school teacher who has been sleeping rough in nearby churches. “She’s in a vulnerable position at the moment,” Linda says. “I have outlined how much she would gain from housing. Employment. Self-esteem. Best of all, she really, really wants to get into housing.”

That’s not always the case, one of the centre’s visiting psychologists tells me. Some people sleeping rough become so adapted to the 24-7 cycle of homelessness that permanent housing becomes something complex and confronting to them. Transitioning to housing often means transitioning back to a kind of reality where one must reacquaint themselves with the detour moment that put them on the street in the first place.

So, here’s the key to reducing homelessness, as Lesley Leece sees it. More homes, as quickly as possible. Public housing advocates have been screaming for more supply for decades. “But it’s not good enough to say, ‘There’s your house, go for it’,” she says. “We need to put them in housing and then support them in housing. When that happens, they do well. We know the answer. That’s the frustrating thing. We know exactly what the answer is.”

Linda Wilson-Marks completes her advocacy letter and sends it off. “Jane has a really good case,” Linda says. “I think she will get a place. She is so warm and caring to all of us. She has this inner strength, this tenacity. I just really want to help her. I know I’ll wake up at 4am tonight wondering if I did everything I could to help her. Did I word that email right? Did I miss something? It’s someone’s life in your hands.” She looks at her computer, shakes her head. “If you dwelled on the enormity of the situation you would crawl under your desk.”

Linda was brought to 3rd Space by a lifelong friend, also named Linda.

They grew up together in seaside Wynnum, eastern Brisbane. The friend was a successful businesswoman. She was beautiful. Wealthy. Perfect marriage. Perfect kids. Linda lost touch with her friend and had tried tracking her down for close to 10 years. She was shocked when she finally reconnected with her childhood friend who told her that she had been using the services of 3rd Space because she had somehow fallen through the cracks of urban Australia. A perfect storm of rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, alcoholism, domestic abuse and depression.

“3rd Space helped keep her alive for three years,” Linda says. The centre helped her friend find an emergency housing unit a short walk from 3rd Space in nearby Harcourt Street. This friend urged Linda to apply for a job at 3rd Space because the friend knew about the size of Linda’s heart; how she’d be the perfect person to advocate for women sleeping rough because she was deeply empathetic; she had a knack for witnessing the most overwhelming social emergencies through the lens of the ones she loved the most.

“She died in that house up the road on Harcourt Street,” Linda says. “The day I found out that she had died was the day I was offered a position at 3rd Space.”

Tears flood her eyes.

“She could be any of us,” Linda says. Some days, as part of her work, Linda finds herself walking new female tenants through that same emergency housing unit on Harcourt Street. She doesn’t talk about any of the home’s previous tenants. She feels it’s always best to focus on the woman who holds the key in her hand today.

Next week The Weekend Australian Magazine will publish an exclusive extract from Trent Dalton’s Lola in the Mirror. Join Trent at the launch event in Brisbane on October 4 which raises money and awareness for the Second Chance Program, and then tours nationally. For details see harpercollins.com.au/trentdalton/

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout