Trent Dalton: Can you tell me a love story?

Perched on a street corner, Trent Dalton asks passers-by for love stories. What they tell him is remarkable.

Bad news this morning from someone I love. This heart of mine is so strong that it will pump enough blood in my lifetime to fill a football stadium. This heart of mine is so weak that it can be broken by eight words in an email.

Raise your left hand and count all the people who you get to love unconditionally and all the people who get to love you unconditionally back. Count them on your digits, starting at your left thumb. This is your left-thumb love. Easy to identify a left-thumb love; they’re more than likely the person closest to you right now, standing over there by the toaster or still snoozing in bed three centimetres from your left elbow. Keep counting, and if you make it to your right hand you’re a lucky person. Keep counting, and if you make it to your toes then, by law of the universe, you are henceforth forbidden to complain about traffic and avocado prices. Some people can’t make it to their first pinky. Some people can’t even make it to their left thumb anymore. But that doesn’t mean all of those people have given up the count. It’s all very simple, really. We must wake, we must brush our teeth, we must make ourselves a coffee and we must keep counting. Bad news this morning from my right-hand index finger.

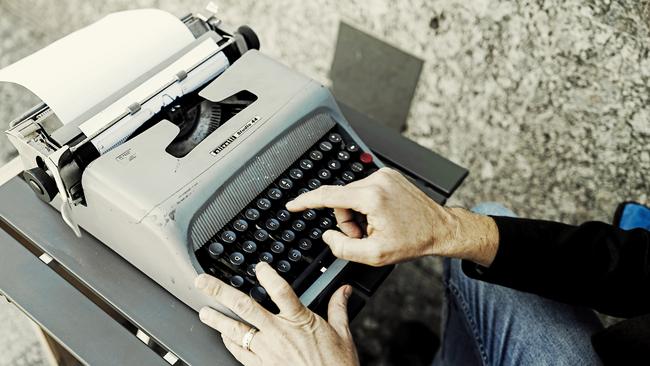

Truth is my heart’s a shambles more often than not. Faulty, defective, ill-built, clapped out and gassed, good-for-nuthin’, op-shop-bargain-bin-poor-excuse-for-a-pump. Always breaking down on me, always pooling up that same old blood inside me, laced with a tricky bottle-lust that’s devil-bent on reducing my world to one big dumb sentimental writer’s choice between two solutions rarely far from reach: the red wine or the black ink. Today, I choose ink. Today, I choose to lug a writing desk and a 1960s sky-blue Olivetti Studio 44 typewriter to the corner of Adelaide and Albert Streets, by the King George Square bus terminal in Brisbane’s CBD, where I will sit for six hours this blue-sky Tuesday and type notes and observations and stories on human love and connection because this, and this I know from experience, will surely unbreak my big dumb heart.

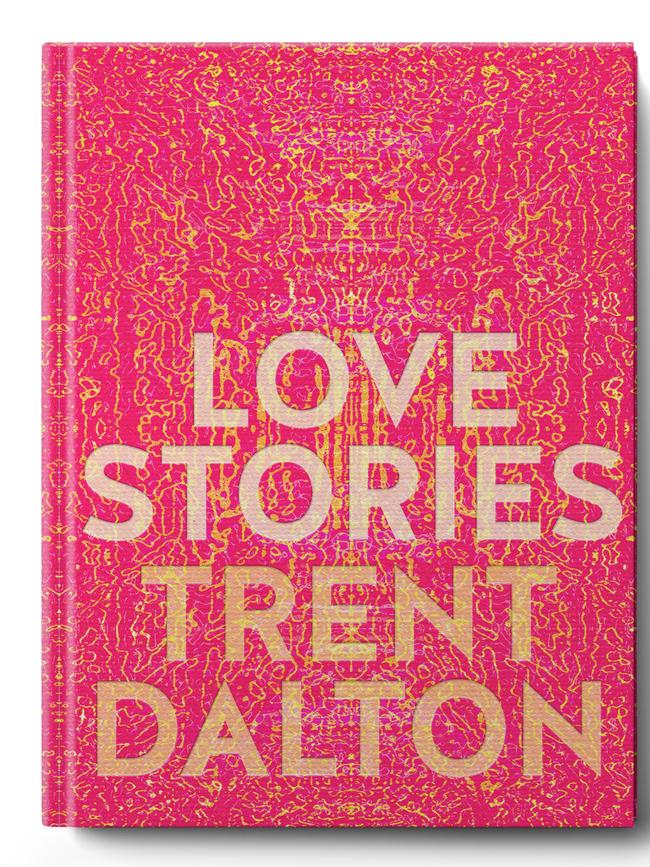

A six-year-old girl named Julian passes my writing desk swinging off her mum’s hand like it’s a schoolyard monkey bar. Julian inspects my old Olivetti, running a hand over the carriage return arm, wide-eyed and curious, as though she might be touching the on-lever to a strange and clunky time machine. She reads the sign that’s leaning against my desk: SENTIMENTAL WRITER COLLECTING LOVE STORIES. Julian eyes a stack of books beside the typewriter. Ten copies of a thickish book I just wrote called Love Stories.

“Why are you sitting here?” Julian asks.

Then I pull the carriage return arm on the Olivetti and I travel nine months backwards in time to the funeral of my dear mate’s mum. Kath Kelly. Earth angel of Jack Street, Gordon Park, Brisbane. She died on Christmas Day, 2020, aged 89. Kath knew the secret: lead a life so full and selfless that when you’re dead latecomers will struggle to find a seat at your funeral. I remember standing with my mate in the summer-baked parking lot of the Albany Creek Memorial Park after the service. As per Kath’s wishes, we all drank the cans of XXXX Gold beer she left in the fridge when she was rushed to hospital. We spoke about how much she lived for words and writing, language and letters. My mate had shown me a scrapbook with articles she kept from my journalism, stories she cut out from this very newspaper. He showed me the letters she furiously typed to editors and politicians and powerbrokers across Queensland, fighting for women’s rights, human rights and everybody’s right to resist being a knucklehead. All those letters she typed on her beloved sky-blue Olivetti Studio 44 typewriter.

“I got somethin’ for you,” my mate said.

Then he opened the rear door on his SUV and he pulled out Kath’s beloved typewriter. He held it for a moment in his arms and then he handed it to me. “Mum wanted you to have it,” he said.

On the corner of Adelaide and Albert Streets, Itake a copy of Love Stories and hand it to Julian’s mum. Her name is Maria Fuimoano and she says she’s taking Julian to the Queensland Museum across the brown snake Brisbane River. “What is this?” Maria asks, looking at the book’s title.

Weeks after Kath’s funeral I phoned her son and asked if he’d mind if I tried to write something beautiful on his mum’s typewriter. Something filled with love and depth and truth because Kath was loving and deep and true. I said it wouldn’t be cynical and glib because I can’t do cynical and glib anymore. The global market for cynical and glib has been flooded. Some 4.8 million people and counting are dead from a virus and, hell no, I don’t feel like being sarcastic. I feel like being deep and true.

“It’s a book of real-life love stories,” I explain to Maria. “Told to me by strangers who passed this very desk on this very corner.”

I spent two months walking the streets of Brisbane asking roughly 100 strangers the same simple question: “Can you please tell me a love story?” Then I sat for weeks on end on this corner with a sign saying, SENTIMENTAL WRITER COLLECTING LOVE STORIES, DO YOU HAVE ONE TO SHARE? By some miracle, 100 more strangers stopped and told me love stories from the bottom of their pandemic-wearied hearts. I typed all my notes and observations on Kath’s Olivetti and then I turned all those notes and stories into a book. You wouldn’t believe the stories people tell you when you take the time to listen.

A blind man yearns to see the face of his wife of 30 years. A divorced mother has a secret love affair with a travelling priest. A young actress microscopically deconstructs the day her heart snapped in two. A widower miraculously finds a three-minute video recorded by his wife before she died. A tree lopper’s heart falls in a forest. A working mum contemplates taking the photographs of her late husband down from the fridge. A young man plots a surprise public marriage proposal to his boyfriend. A girl writes her last letter to the man she loves, then sets it on fire. An ageing gigolo regrets the one that got away. A palliative care nurse helps a dying woman converse with the angel at the end of her bed. A renowned 100-year-old scientist ponders the one great earthly puzzle he was never able to solve: “What is love?”

Endless stories. Human stories. “Nuthin’ but love stories,” I say to Maria. I tell her she can keep the book but I must ask one thing in return. I point at Julian. “Can you tell me how much you love this girl?” And Maria looks at her daughter and smiles and shakes her head and I’ve seen that look before. “I love her to the moon and back,” Maria beams.

“Hey Julian, how much do you love your Mum?” I ask. The question makes her bounce on the spot. “So much,” she says. “More than the world.” The girl starts jumping up and down and looking to the sky. She sees something we can’t see beyond the clear blue blanket. She points at it because she wants us to see it too.

“I love her to the starrrrrrrrrrrrs,” she yells.

And my big dumb heart begins to unbreak.

“What is all this?” asks Maree Roberts as she takes a seat in the empty chair beside my footpath writing desk. “A cheap stunt,” I explain. “I’m handing out copies of my new book, Love Stories, in return for more love stories. You could call this a love story swap meet. A love story trading post.”

Maree tells me about her husband, John. They met when she was 15. They were both part of the Brisbane Gang Show, an annual variety show run by the Scouts. She remembers the very month she saw him. November, 1965. John was up on stage singing a song called On the Crest of a Wave.

That title could be the story of their love. Riding the crest of a wave for 56 years now and that wave never crashes, only gets fuller and wider. It’s so wide on the crest now there’s room enough for the 19 children and grandchildren whom she loves unconditionally. That’s 10 fingers and nine toes. She’s made it to her right foot and then some. She gives me an insight into what it feels like for her to be in the presence of her grandchildren, Adam, four, and Hank, 10. Just the thought of them makes her sit back in wonder in her chair.

“True love in its purest form,” she explains. “They hug so long and they want and need nothing from me. They just give. Total unconditional love. It’s amazing.” We talk about the pandemic and how it stripped everything back to the only things that matter. Health. Family. Future. Love. “How much did this pandemic teach you that all that matters are those 19 people in your life?”

“Well,” she says. “I knew that beforehand. I really did.”

I ask Maree for her best marriage tip after 50 years in the game. “There’s no ‘dead right’,” she says. “Do you want to be happy or do you want to be dead right? There’s no dead right.” She accepts a book in thanks and pushes on up the street.

Two metres from my writing desk stands Kim and her two friends from the anti-Chinese Communist Party petition group that always shares this busy street space. Kim was one of the friends I made sitting for weeks on this corner. There was also a man named Reuben Vui, a kind-hearted Kiwi signing people up to child sponsorship programs. He told me a love story about why he has leaf-shaped fragments of his grandparents’ wedding rings permanently fixed to his teeth. Some days I was joined at my desk by Tony Dee, a crooner living with spina bifida who sings note-perfect Sinatra love songs from his wheelchair at the entry to King George Square. Some days I was joined by my new busker mate, Jean-Benoit Lagarmitte, who plays drums on an upturned and empty Osmocote fertiliser tub. Jean-Benoit was born in the Rwandan Civil War and left for dead under a tree as a baby and he might be the happiest man I’ve ever met.

Kim was kind enough to tell me to lighten up. We had been discussing the myriad complexities of love. I was talking about how all our worries and fears so often stem from love. “You too heavy with thoughts,” Kim said. She made a waving-me-away gesture with her hand. “You need to go love someone,” she said. “You unhappy, go love someone. You anxious, go care for someone. You stop thinking about self. All worries go away. You love someone, you lighten.”

I love someone. I lighten. We love. We lighten. Thanks again, Kim.

“Hello Trent,” says a woman with a face I’ve seen before.

She smiles, wide and knowing.

“It’s Alison’s mum,” she whispers.

“Mrs Hipwood?” I gasp.

“Yes!” she beams.

Coral Hipwood, mother of Alison Hipwood, my first hopelessly ambitious primary school crush.

“Your daughter was the first girl I ever kissed!” I gasp, amazed by Coral’s presence.

“I know,” Coral says.

We kissed beneath the Love Tree, a shady eucalypt on the edge of the Brighton State School oval covered in pocketknife love hearts and initials of naive schoolyard romantics. The Saturday after that brief but perfect kiss, my best mate Ben Hart and I rode our bikes up to the Love Tree and I carved a message of lifelong devotion into its trunk. AH + TD TL4E. True love forever. That was the first love story I ever wrote. A handful of letters and numbers etched into a tree. Alison dropped me like a bag of rotten spuds three days later but that love story remained legible for years.

“I carved those letters deep, Coral,” I say.

Coral laughs and tells me Alison married a very good man and is a mum to two beautiful boys.

“Don’t you think this is bizarre, Coral?”

“What?”

“I’m sitting here in the city collecting love stories from strangers and then you walk past?”

The mother of the central figure in the first love story I ever wrote. “Funny how the world works sometimes,” Coral says.

I hand Coral a copy of Love Stories. She promises she’ll read it, cover to cover. “Can you pass it on to Alison when you’re done?” I ask. “She’s in that book. I mean, she’s not in it, but… she’s in it, if you know what I mean?”

Coral smiles and nods.

“I know what you mean,” she says, tenderly. And my big dumb heart begins to unbreak.

Clouds form in the sky and the day rolls on. More strangers stop and we make our heartfelt transactions. Love stories for love stories. A Brisbane poet who goes by the name Minus The Cynic. He shares with me one of a thousand lines he’s written on love: “Time is a convenience store and every day I love you a little bit more.”

A thoughtful and softly spoken Japanese translator named Sakura Tomii stops by my desk and shares with me the secret to eternal happiness. Every day of your life, note at least three things that you love about that day. Here are some love things Sakura has noted in recent days: Rescued a stray dog. Harvested two pumpkins. Made risotto. Sunny winter day. Sewing. New laundry detergent smells good. Eggplant for dinner. Lift from Pilates, thank you Hazel. An email from Dad in Japan.

A woman named Ellen Cuskelly stops at my desk. She wants to tell me how much she loves her aunt, Toni. “She’s always been there for everyone,” Ellen says. “Toni’s always there for her nieces, nephews, grandchildren.” Ellen asks me to sign a copy of Love Stories for Toni and I’m halfway through signing the book when she reminds me of something I’ve forgotten.

“I delivered flowers to you once,” she says.

“You did?”

“Yeah,” Ellen says. “I wasn’t the one who sent the flowers but I made the flowers and delivered them to you at your house. I asked you to sign a book for Aunty Toni then as well.”

“Did I sign it?”

“You did!”

And I remember the flowers now. Beautiful native bouquet, unwieldy and glorious. The whole colourful and brilliant arrangement felt like a walk through the MacDonnell Ranges at sunrise.

“You’re a brilliant florist,” I say. Ellen shrugs. “You must have the best job in the world,” I say. “You spend your days delivering gestures of love to complete strangers.”

“Yeah,” Ellen says.

“You’re like a messenger of love!”

“Yeah, guess I am,” she says. Then she gives a half-smile that has melancholy in it and for a moment it looks like she might be about to tell me something deep and heartfelt about what her job means to her but then she looks at her phone and says she has an Uber to catch. “I wish I could say more about love,” she says. “But I gotta run.”

And Ellen’s gone as quickly as she arrived.

“Love is the thing that makes you want to be a good person,” says a woman named Julie Yamamoto, who works at the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. “Love makes you do what you can in the short time you have. Love is leaving a mark on people. Love is making others believe in themselves. Love is empowerment. Love is everything.”

Julie tells me how much she misses her father, who died in 2012. He was a good cop and a better dad. Community-minded. Worked overtime hours for indigenous communities. Weekends spent coaching and managing penniless sporting teams. Selfless. Thoughtful. And sorely missed. She says his name and it’s good to say the names of the dead because they live a little longer when their names are spoken. Kath Kelly sent an email to me once, when my dad died, reminding me of this notion. Julie’s father’s name was James Sommer.

“Did you tell him how much you loved him before he went?” I ask.

“I definitely did,” Julie says, and tears well in her eyes. “I still talk to him a lot, actually. I keep him updated on things; how Covid’s going. I tell him we can see the light at the end of the tunnel. People think I’m crazy. But I do believe he’s listening.” She shrugs her shoulders. “Somewhere.”

“I don’t think that’s crazy at all,” I say. “I talk to my dad all the time in my dreams. Do you ever talk to him in your dreams?”

“Yes, definitely,” Julie says. “It feels so real. Then you wake up and think, ‘Why did I have that dream at this point in time?’ Then, sure enough, a couple days later, you realise why.”

Another hour passes and suddenly I only have one more book left to hand out. It goes to a passing artist named Jenny Jump. She tells me what it feels like to now be legally allowed to marry the love of her life, Lisa, whose hand she grips while standing at my desk. “I feel like the luckiest person alive,” she says. She raises Lisa’s hand triumphantly and lifts her head to the sky as she makes a loud declaration that anyone within 30 metres of us can hear clearly. “This is the girl I’m gonna marry!” she hollers.

They’ve been together for nine months and the thing Jenny loves most about their love story is how that story runs deeper every day. Jenny wasn’t expecting that. “It grows and expands,” she says, gobsmacked by the notion. “And the funny thing is, now that I’m so full of love, that love has extended to my friends and family, too. I’m closer to them all now because of my love for Lisa.”

Jenny found her left-thumb love. You get that left thumb sorted then all the remaining digits reap the rewards. “I know very little about a great many things,” I explain to Jenny and Lisa. “But there’s one thing I’ve learned a great deal about in the past few months talking to strangers in the street.” I leave a pause for dramatic effect. “Love is boundless,” I say.

There is precisely as much of it as we choose to take from the world and as much of it as we choose to give to the world. No more. No less. And yet boundless.

Unsolicited love sermon complete, I pack up my desk and lug Kath’s beloved Olivetti back to my car three levels beneath the earth in the King George Square car park. I’m sitting in my car at 2.38pm when an Instagram message lands in my phone from Ellen Cuskelly, the woman who delivered the bouquet of native flowers to my house.

Dear Trent, I met you on Adelaide Street today. Once I got into my Uber I realised that I didn’t give you a signed book’s worth of talk about love. In fact, due to my fluster, I wasn’t entirely honest with you in our conversation. Unfortunately, the flower shop closed in the depths of the first year of Covid. I don’t work with flowers anymore. I put a lot of love into that place and into every arrangement I made there. For a long time, I felt the closure was a personal failure. I’ve since come to believe things happen for a reason and I love that I had the courage to put myself out there, creatively. I’m sure you know the vulnerability that comes with that.

So, here’s my hot take on love. Obviously, there are the big loves, the romantic loves, or your family or friendship loves. But there are also little, more subtle loves that are ever-present in the unfamiliar and the mundane. I believe we are walking through little loves every day. I think it’s hard to see the little loves when we feel pulled in all directions, as so many of us do these days. When you don’t have time for yourself, you don’t have space for the little loves. You might miss a warm, fleeting interaction with a stranger, the first jacaranda flowers of the year, or you might be too agitated to notice the possibilities around you when your Uber driver is stuck at a traffic light! I think noticing the little loves enriches the big loves of your life. In fact, they might even be a necessary precursor in fully experiencing big loves. Today I experienced many little loves in a mundane day of errands. One of which was running into you on Adelaide Street.

Thank you for the book and for your generosity. Aunty Toni is stoked!

Love, Ellen Cuskelly

Then a text message lands soon after Ellen’s message. A few brief and perfect words from my left-thumb love, my wife Fiona. Pork. Potatoes. Pumpkin. Greens. Apple sauce? Bargain City side table for Beth? I put the car in drive and tap on a Spotify playlist I’ve been rabbit-holing for weeks. Best of The Kinks. The car circles three levels out of the earth to the sound of Waterloo Sunset and my big dumb heart begins to unbreak.

Subscribers to The Australian have the chance to win a copy of Love Stories. Visit theaustralianplus.com.au to enter.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout