Even when it turns personal, science is still their watchword

In our own medical research peloton, as co-medical directors of Melanoma Institute Australia, we extend a track laid by those who have gone before us. Each generation of scientists and researchers pushes further, building on scientific evidence to create better and more effective treatments and save lives.

But at each move forward, there must be courage and bravery: courage to be creative, to think outside the box and come up with something different; bravery to say yes to something new with unknown outcomes.

For us, this courage and bravery became personal when we were faced with a sudden problem; one we could only tackle with science.

Everything changed in May 2023, when Richard suffered a seizure in a hotel room high in the mountains in Poland. It came a day after a conference in Krakow where he had delivered a day of presentations. As the most published melanoma pathologist in the world, who is sent thousands of the most difficult-to-diagnose melanoma cases each year for review, invitations to address international conferences are common. But this event was not common. The seizure came without warning.

Doctors at the local hospital performed preliminary investigations before transferring Richard to University Hospital in Krakow. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was performed the same day. It quickly became clear the diagnosis and prognosis were dire.

On the other side of the world, Georgina received the MRI scans via text from Richard’s wife, Katie, almost in real time. She immediately alerted our team of Melanoma Institute Australia colleagues who are world-leading experts in neurosurgery and radiology. Each concluded that the ill-defined patch of white tissue in the brain looked like a particular type of terminal brain cancer: glioblastoma.

Generally, the earlier the stage of your cancer, the less intensive the treatment and the better your chance of survival. But glioblastoma is different. There is no chance of “catching it early”. From that first mutated cancer cell, all glioblastomas are grade IV. Everyone receives the same treatment, and nearly everyone dies within two years. This subtype of glioblastoma, however, was deemed “the worst of the worst”, with an expected median survival of just 14 months.

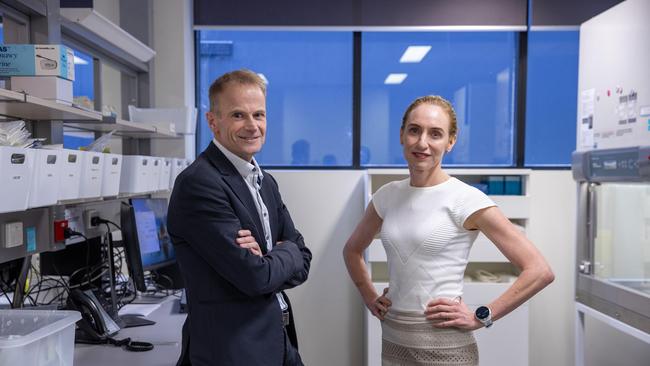

We have been colleagues for the past 20 years. Our skill sets are complementary. Georgina is a medical oncologist who uses drug therapy to treat cancer. She has been instrumental in the immunotherapy drug revolution with one of the largest clinical trial programs in the world. Richard is a pathologist who has redefined melanoma diagnostic techniques and led global advances in disease staging and understanding of pathological responses to treatment. We also co-lead a melanoma translational research laboratory at the University of Sydney, where one of our streams of research focuses on converting scientific breakthroughs into new treatment pathways for patients. Together we have problem-solved, strategised and broken new ground – all underpinned by strong science.

Here was a “problem” with the most tragic of personal impacts – but a “problem” just the same.

Compared with many other cancers, treatment for this subtype of glioblastoma seems frozen in time. It involves a toxic regimen of chemotherapy and radiotherapy that, in the original clinical trial, extended survival by several months.

Being a melanoma medical oncologist was bleak in the early to mid-2000s. Stage IV melanoma was essentially a terminal cancer, just like glioblastoma, with most patients dying within months. Only five per cent of patients with advanced melanoma survived five years. But thanks to science, things began to change. Drug clinical trials led by Georgina and the Melanoma Institute Australia trials team, along with those of our international colleagues, started producing truly incredible results using a new class of immunotherapy drugs. More than 50 per cent of stage IV melanoma patients were responding to the new treatment and, crucially, these responses were sustained. Year after year, patients from these early trials were coming back for surveillance checks – still living, still well, with no sign of the melanoma that had previously riddled their bodies. It felt like the Holy Grail – the discovery of drugs that were able to cure cancer.

The scientists who discovered key mechanisms of activation of the immune system, particularly activation of T cells, James P Allison and Tasuku Honjo, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2018.

Today, these drugs are considered the most important advancement in cancer medicine, likened to the discovery of penicillin. If you receive a diagnosis of stage IV melanoma today, the chance of being cured is greater than 50 per cent. The same immunotherapy drugs are extremely effective in early-stage melanoma too, which means the number of new stage IV diagnoses will continue to shrink. Our goal at Melanoma Institute Australia – zero deaths from melanoma – might seem glib at first. But it is deadly serious.

Importantly, these breakthrough treatments developed for melanoma are now also being successfully used in other cancers, such as lung, kidney and a subset of breast cancers, to name a few. This is the power of science – advances in one cancer can, and do, help others.

But what soon became clear to us was that the subtype of glioblastoma that affected Richard had not been part of this revolution.

Behind every new cancer treatment lies a clinical trial. This is science. This is how innovative cancer treatments become new standards of care.

Georgina tapped into her vast drug-therapy networks and clinical trial databases, and it soon became clear there were no suitable glioblastoma clinical trials available anywhere in the world for Richard. For Georgina, who leads a clinical trials team that runs more than 20 drug clinical trials at any one time, that was a disappointing realisation. Here was a subtype of brain cancer for which treatment and prognosis hadn’t changed in two decades. Despite scientific breakthroughs transforming other once-incurable cancers, such as melanoma, the clinical trial landscape in glioblastoma was limited.

After trawling through international publications and talking to trusted key opinion leaders in neuro-oncology, Georgina realised immunotherapy had been tried in sub-optimal conditions and with only a single drug. The approach that would optimise the chance of a response was combination immunotherapy given before surgery (neoadjuvant). Georgina proposed using the same type of immunotherapy drugs that had transformed the treatment of melanoma, but in a special combination that would be more likely to work in brain cancer, a cancer that is not considered to be immunotherapy-responsive.

We also discussed the rationale of the standard approach with dozens of colleagues at home and around the world, asking about the level of scientific evidence to support the extent of surgery and radiotherapy, and the current “standard of care”.

So there is the power of science. As scientists and medical researchers we felt we had an obligation to do something different, something bold, and something that could push the glioblastoma field forward. Our situation was unique. Two cancer researchers and clinicians: one now the “patient”, with an intricate knowledge and understanding of what diverting from standard treatment could mean, the other a medical oncologist with a bold plan for a world-first experiment to apply melanoma science to glioblastoma.

Cancer cells are so genetically altered, they bear very little resemblance to their normal predecessors. They are able to grow silently and undetected by the immune system until they finally poke above the surface with clinical signs and symptoms like a headache, a lump or a cough. Immunotherapy drugs remove this cloaking ability and let the immune system see the tumour for what it is. Unleashed by the drugs, immune cells learn how to recognise and attack the tumour and, critically, retain these abilities long after the tumour has been cut out. After surgery, you’re body is left with a comprehensive immunological memory of what the tumour looked like and the ability to detect and thwart any new outcrops from cells left behind.

While great in theory, and fantastic in practice in melanoma, neoadjuvant immunotherapy is a radical idea in the setting of brain cancer. Alongside the heart and the lungs, the brain is within the triad of our most precious, life-giving organs. It is protected within a rigid bony skull that will not yield to pressure from a mass growing inside. Surgery needs to happen as quickly as possible, with many glioblastoma patients not having the luxury of waiting two weeks. Furthermore, anything that might cause an increase in intracranial pressure – for example, an influx of immune cells and fluids – could be deadly.

But science is about doing the best we can with the information we have available and building on lessons already learned.

There were an incredible number of unknowns in this situation. Evidence to date has shown brain tumours do not respond well to immunotherapy. But it’s not known if that applies to newly diagnosed tumours that have not already been subjected to chemotherapy and radiation. It was also believed likely that immunotherapy drugs would not be able to penetrate brain tissue. But was that true? Then there were on-the-ground unknowns: would the drugs cause a severe adverse reaction? Would the tumour progress rapidly? Would neurological symptoms develop that required corticosteroids that would counteract the immunotherapy? Only a cancer researcher who clearly understood the risks could make a decision to undertake such experimental treatment. It could prolong or shorten whatever life was left.

Backed by strong melanoma science, and with a determination to – at the very least – generate scientific learnings to progress the glioblastoma field, we pushed ahead. It wasn’t a difficult decision, given our scientific understanding and the poor prognosis with standard treatment. But it was, and still is, an emotionally challenging journey. The focus was on the things we could control: being scrupulous in our efforts to research what was known, extensively canvassing the opinions of neuro-oncologists, and developing clinical and laboratory systems to capture and document scientific evidence and data from the experimental treatment. The scientific data we have already generated by comparing Richard’s tumour before and after neoadjuvant immunotherapy are exciting for the field.

Science, and its inherent uncertainty, has been maligned of late. For the most part, Australians have been highly trusting of science; in many ways, the scientific approach aligns with traditional Australian values of teamwork, mateship, courage, hard work, humility and honesty.

But in a modern world dogged by misinformation and driven by profit, and where people are being asked to make important personal, financial and social decisions based on science, there can be a sense of scepticism. Research shows some Australians suspect modern scientists and scientific institutions of having ulterior motives.¹ Who exactly is driving the research questions and who will benefit from the results? Is the threat as big as it is made out to be? How far away is it? What are we being asked to believe, to buy, to sacrifice? What behaviours are we being asked to change in order to combat that threat?

In our situation, the scientific motive and urgency to deal with our problem is difficult to argue with – a terminal brain cancer diagnosis where treatment hasn’t changed in almost 20 years. When the threat is harder to see, we have to rely on trust. That’s what we have learned from our work in melanoma treatment. Take sun safety, for example. More than half of young Australians say they feel more attractive when tanned.² And it goes further than looks. There is a perception that a tanned person is healthy and relaxed. But science tells us there is nothing healthy about a tan, that tanned skin is damaged skin, and that a tan is skin cells in trauma, producing melanin to try to protect from further UV damage. Medically, a tan is not desirable at all. We know this thanks to science, which also tells us that skin cancer is preventable in up to 95 per cent of cases by being sun safe.

The challenge lies in the fact that tanning doesn’t feel inherently threatening, and the consequences aren’t likely to be seen until some years in the future. So, how do we get Australians to trust in the science, take the risk seriously, and act now? This is a challenge we as a nation are still grappling with, as our tanning culture continues to impact the behaviour of impressionable young Australians in particular.

Science is deeply embedded in our modern life. From the Covid-19 pandemic to climate change, cancer prevention to genetically modified crops, we are constantly required to engage with science on some of the biggest challenges of our time. But science will not always give us the answers and solutions we would like; they can seem incomplete, unpalatable and excessive.

Twelve months have now passed since we began this experimental treatment, and Richard’s latest scan remained recurrence free. There are no answers as to what subsequent scans will show. Science doesn’t allow us to predict what will happen next, but it does allow us to continue to gather evidence, build a foundation and move the glioblastoma field forward. The next step is to use the data we have gathered to develop and open a clinical trial, and test the treatment on a wider group of glioblastoma patients.

Scientific progress is fuelled by a unique combination of trust and uncertainty. Science allows us to believe that progress can be made, continually. We just need to have the bravery to take the action that tackles questions when they arise. The scientific community needs to think big, be bold, be courageous. And we must work together.

To say we are proud of what we and our team have achieved is an understatement. The breakthroughs our team has made in melanoma treatment have transformed survival rates across the world.

Science is our life passion. It is equal parts rewarding, intriguing, challenging and frustrating. Science is also powerful – it is the life blood for advances that have transformed societies and benefited billions across the globe for centuries.

Big Ideas

The stories Trent Dalton is most proud of

For 23 years, as a working journalist, I have been documenting Australians who simply refuse to succumb to whatever pervading darkness threatens to blacken their light. These stories are the keepers.

The trendy disparagement of science is un-Australian

Richard Scolyer and Georgina Long faced the worst possible scenario when Richard was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. The melanoma researchers fell back on their medical knowledge to make a brave decision.

The turning point for all strong women? It’s not motherhood

It’s the pain and confusion that is my strongest memory of the worst year in the lives of all women, I’m sure. It was my first insight into the complexity and competition of womanhood.

The balance is broken: What now for democracy?

Radical shifts in social order; technologies that shape as foe rather than friend; erosion of faith; an end to truth and facts. The strength of our good society is about to be put to the test.

‘No one is disadvantaged just because they are Indigenous’

No meaningful change comes from selling ourselves short through guilt politics. It comes from understanding our history in its entirety.

Ideas are the source of all power in human affairs

Political power may grow out of the barrel of a gun but it is an idea that compels someone to pull the trigger, to raise an army, to start a war.

There is no choice: a Holocaust survivor’s view of courage

A difficult choice is speaking out against the populist but morally reprehensible behaviour of the crowd. If the tipping point between democracy and anarchy is to be avoided, we, you and I, need the courage to fight for our democracy.

What 1184 days’ jail has taught me about liberty

The Australian journalist who was detained for more than three years in China reflects on the true value of freedom.

60 most influential people of the past six decades

To celebrate The Australian’s 60th anniversary, this masthead has brought together a list of those who have had an impact on all our lives.

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

Professor Georgina Long AO and Professor Richard Scolyer AO are co-medical directors of Melanoma Institute Australia and joint 2024 Australians of the Year

1. Tranter B, Lester L, Foxwell-Norton K, et al. In science we trust? Public trust in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projections and accepting anthropogenic climate change. Public Underst Sci 2023;32:691-708.

2. Abbott LM, Byth K, Fernandez-Penas P. Tanning, selfies and social media. Australas J Dermatol 2019;60:82-4.

Medical research is a team pursuit – not unlike a peloton of cyclists, where the laws of physics dictate that riders take turns to lead, sheltering others from headwinds and enabling the team to progress faster than if riders were competing alone.