There is no choice: a Holocaust survivor’s view of courage

A difficult choice is speaking out against the populist but morally reprehensible behaviour of the crowd. If the tipping point between democracy and anarchy is to be avoided, we, you and I, need the courage to fight for our democracy.

For her there was not. Widowed at 28, when my father was murdered during the Petlura uprising in Lwow, then in Poland, she lost almost her entire family and that of my father in a number of death camps – Treblinka, Belzec, Auschwitz. Thrown out of her apartment and having to search for a room in the emerging Lwow ghetto, she later fled into hiding weeks before the ghetto’s liquidation. To my mother, these were not courageous choices, they were imperatives for survival. Looked at objectively, each choice, each action, was a badge of courage.

Courage: a word laden with so much subtext, with so many interpretations, with so many facets – physical, emotional, moral. At its heart, it represents bravery, even heroism; but depending on the circumstances, it can also encompass perseverance, kindness, empathy, quiet dignity in the face of suffering or rejection.

At Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Jerusalem, there are avenues of trees honouring The Righteous Among the Nations. They are the non-Jews who saved Jews during the Holocaust. Many people are familiar with the name Oskar Schindler, made famous by Thomas Keneally’s book Schindler’s Ark and popularised by Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List.

Schindler’s name may be the one that is frequently remembered in popular culture, but Yad Vashem has honoured 28,217 righteous, the greatest number of whom, 7232, came from Poland. This is significant, because in Poland not only the person hiding a Jew would be shot, but so would the entire family.

Elie Wiesel, survivor, writer, the interlocutor of those who failed the world during the Holocaust, bemoaned the fact there were so few. Of all the millions in all the countries where Jews were being murdered, only 28,217 were recorded as having the courage to save Jews. Statistically, Elie Wiesel is right. The number of those who had the courage to act was, proportionally, abysmally small.

I understand Wiesel’s grief, but I am grateful there were so many. Hypothetically, we are all heroes. We all think we would do the right thing, the ethical thing, the noble thing. But in the face of losing your life and risking the lives of the people you love, would you have the courage to save a stranger? Would I? In the depths of the night, when truth is not easily avoided, my answer is “I do not know”.

And yet, there were 28,217 who are known to have done so. We cannot deplore the vast number who did nothing. We must instead celebrate those who, at the risk of their lives, acted with humanity. And with courage.

What made these people stand up when others didn’t? There was little commonality among the rescuers. They came from 44 countries, spoke different languages, and practised different religions or none. There were academics and people who were illiterate; workers, servants, resistance fighters, policemen, nuns, priests. There were also those who, unnamed and unrecognised, brought food to the fences of the death camps or sheltered Jews for a day, or a year. And a very few like the soldier who told my mother to take me from the queue waiting to be uploaded on our way to Belzec extermination camp, knowing his act, if discovered, would bring swift and brutal retribution. The only common thread was courage, based on empathy, on a sense of decency and on the ability to think independently, not to follow the herd.

It is easy to be overwhelmed by events. Should I act or remain passive? War is a big event. In the face of war’s inhumanity, one can become paralysed by fear or by circumstances. By acting bravely, will I be putting myself at risk? Will I be maimed or killed? None of us can know how we would act until we face such a situation, and yet acts of courage, indeed heroism, abound in war.

In everyday life, choices also must be made. Do I stand up for my colleague who is being derided by our supervisor, and suffer the consequences? Do I call out the teacher who is mocking a vulnerable fellow student? Do I confront the louts on the train crowding in on a young girl who is clearly terrified, and then become the target of their abuse?

A myriad such decisions face us every day. For some, the answers are equivocal; for others, like my mother, there is no choice. If action is required, you take it.

For many of us, small but difficult choices can test our courage. The daily fight against pain; retaining grace during prolonged and possibly unsuccessful treatment; dealing with poverty and deprivation with dignity and strength: all these take a silent, unceasing courage, a courage often unrecognised.

These choices do not necessarily involve grand actions, nor are they acts of bravado or foolhardiness. Neither of those represent courage, although in certain circumstances they can spur us on to courageous acts.

A difficult choice is speaking out against the populist but morally reprehensible behaviour of the crowd. It takes courage to speak out at a parents’ group meeting, when you know your view will be unpopular. It takes courage to write to someone in a minority group who is facing discrimination and to say this is not behaviour that I condone. This is the type of courage that has heartened and strengthened me as an Australian Jew. Each message I have received, whether from a school friend from the early 1950s, or from a golfing friend of my husband, or from friends from university with whom I had almost lost contact, each message is a gift of courage.

These are messages from people who are not prepared to stand by and watch the civility of their country being eroded. These are people who reassure me this is not their Australia, that the antisemitism that has become prevalent, normalised, is not what they want to see in their society. These are all acts of courage, acts of grace which show an empathy and understanding greatly needed if we are to retain our civility.

How to account for the dichotomy between those who show courage and those who do not? Is it purely an instinctive reaction that prompts acts of courage or is there something greater at play?

Much has been written about the psychology of courage, about the ability of some people to rise above even their own expectations and act in a way that makes this world not just tolerable, but a better place for us all. What gives hope is that almost invariably, people who have performed heroic acts, when questioned on how they found the courage, look startled and respond, “What I did was natural; it needed to be done. I was there and I did it”. An echo of my mother – “is there a choice?”

For some there is; for others, clearly not.

This brings us to where we stand today. We are possibly, and I hope it is not a probability, at the tipping point between democracy and anarchy. This is not meant to be alarmist; it is an observation that the danger signs are there.

The words freedom of speech and the right to protest are being thrown around with a casualness and disingenuity that is staggering. Everyone who values democracy – and there is little doubt that most Australians do – considers freedom of speech and the right to protest to be basics of democracy. But they also understand that these rights are not absolute; they come with responsibilities.

The right to free speech does not give you the right to dox and expose others to vile abuse, or to harass and abuse people as they go about their lives.

The right to free speech is rightly safeguarded by defamation laws and, theoretically, by laws against hate speech and incitement to violence, among others. Free-speech proponents would do well to remember those limitations and the concomitant responsibilities.

The right to protest does not mean you can close off city streets so that an elderly man must walk 12 blocks in central Melbourne because public transport and cars have been blocked. The right to protest does not mean you can close major freeways so that a woman is forced to give birth by the side of the road because cars and ambulances cannot pass. The right to protest does not mean that Jewish students cannot safely attend university campuses, nor does it give the protesters free rein to demand that universities breach non-confidentiality agreements to satisfy a political agenda.

What arrogance, what inhumanity to think that your right to state a view trumps everyone else’s right to lead a normal life. By all means speak freely, by all means demonstrate, but do so with civility, with consideration, and not in a manner that is intimidating, harassing and a danger to others.

At this very uncertain time, many people are saying this is not the Australia in which I grew up. In letters to the editor, in distressed comments online about violent protests and obscene and divisive language, and on social media, there is a repeated outcry against what this country is becoming.

While these comments are sometimes barely heard above the loud and vicious noise of an anarchic minority, we are beginning to reach the point where brave people are speaking out. Such people understand that the silent majority is, by its very silence, powerless. They have gathered up their courage like an offering to the rest of us, to ensure we continue to be a democracy.

Courage is core to keeping that which we value. The failure to rein in antisocial behaviour, to call out antisemitism from the start, the lack of courage in leaders at all levels – politicians, teachers, university heads, parents at a school where five-year-olds are being politicised – all this means our democracy is being eroded. The rights of the majority are becoming subsumed by the perceived rights of the loud minority. At some stage, the members of the silent majority need to show courage to say: “Enough is enough!”

If the tipping point between democracy and anarchy is to be avoided, if we value a truly democratic, inclusive and empathetic society, we, you and I, need the courage to fight for our democracy.

It is not enough to bemoan what is happening. “Is there a choice?” must become the norm, not the exception.

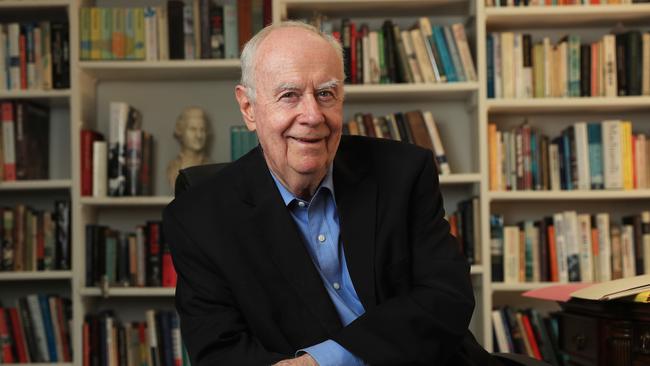

Nina Bassat AM is a former lawyer and was president of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry

More Coverage

Big Ideas

The stories Trent Dalton is most proud of

For 23 years, as a working journalist, I have been documenting Australians who simply refuse to succumb to whatever pervading darkness threatens to blacken their light. These stories are the keepers.

The trendy disparagement of science is un-Australian

Richard Scolyer and Georgina Long faced the worst possible scenario when Richard was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. The melanoma researchers fell back on their medical knowledge to make a brave decision.

The turning point for all strong women? It’s not motherhood

It’s the pain and confusion that is my strongest memory of the worst year in the lives of all women, I’m sure. It was my first insight into the complexity and competition of womanhood.

The balance is broken: What now for democracy?

Radical shifts in social order; technologies that shape as foe rather than friend; erosion of faith; an end to truth and facts. The strength of our good society is about to be put to the test.

‘No one is disadvantaged just because they are Indigenous’

No meaningful change comes from selling ourselves short through guilt politics. It comes from understanding our history in its entirety.

Ideas are the source of all power in human affairs

Political power may grow out of the barrel of a gun but it is an idea that compels someone to pull the trigger, to raise an army, to start a war.

There is no choice: a Holocaust survivor’s view of courage

A difficult choice is speaking out against the populist but morally reprehensible behaviour of the crowd. If the tipping point between democracy and anarchy is to be avoided, we, you and I, need the courage to fight for our democracy.

What 1184 days’ jail has taught me about liberty

The Australian journalist who was detained for more than three years in China reflects on the true value of freedom.

60 most influential people of the past six decades

To celebrate The Australian’s 60th anniversary, this masthead has brought together a list of those who have had an impact on all our lives.

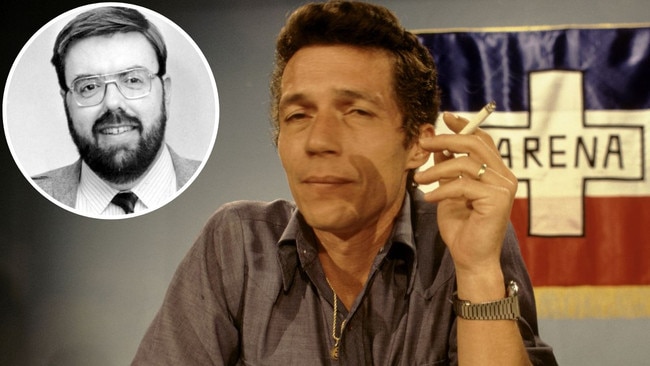

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

People used to say to my mother, “You are so brave”. A whimsical look would cross my mother’s expressive face, her eyebrows would rise, and she would respond, “Is there a choice?”