This is the most evil man I’ve ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

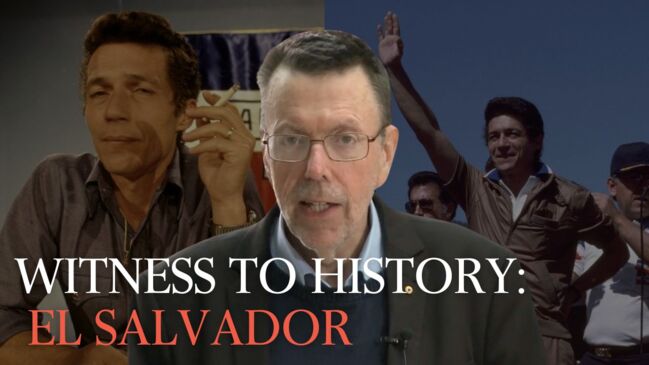

Greg Sheridan faces a pistol-packing politician in the first of our 60th anniversary series looking at how we have brought you the news.

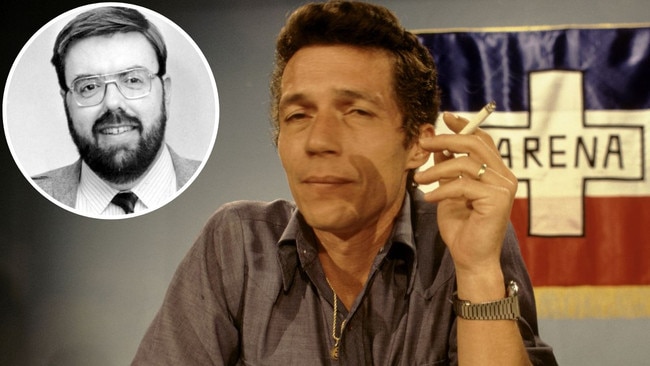

Roberto D’Aubuisson was, I think, the most evil man I’ve met. In March, 1987, we stood, tense, facing each other, a few metres apart, like two gunslingers in a spaghetti Western, except I was holding a notebook and pen, he was cradling, fondling really, a pistol.

D’Aubuisson ordered the murder of San Salvador’s Archbishop Oscar Romero in 1980. A former soldier, he was the leader of El Salvador’s notorious death squads.

Getting to interview D’Aubuisson was challenging. He hated “gringo” journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again.

I was the paper’s Washington correspondent. Ronald Reagan’s central America policies, especially concerning El Salvador and Nicaragua’s civil wars, were hot. I convinced our editor, Les Hollings, to send me to El Salvador. Les, whom I loved, gave me one mournful instruction: “Make sure you file your story before you get taken ’ostage!”

I took a Salvadoran plane from Miami. When it landed, passengers cheered and applauded.

El Salvador was hot, poor and violent. Death squads, communists, the partially reformed army, and regular street gangs all killed people.

I’d tried unsuccessfully to set up appointments in advance.

In San Salvador, I employed a brilliant Peruvian photographer and translator Juana Anderson, who introduced me to the foreign press corps.

They were gold. Journalists compete ferociously but always look out for each other in tough environments. The Washington Post’s William Branigin generously briefed me on Salvadoran politics. I hung out at the residence of one of the wire agency chiefs.

Though I had nothing to offer, these seasoned correspondents welcomed me like a brother. But it was impossible to get important appointments. I spent one happy morning interviewing regular, friendly, hospitable Salvadorans on the street. I visited all the pro-left NGOs, but couldn’t get the president, Jose Duarte.

I was determined to deliver something to justify Les’s faith. I rang the US embassy and got the junior media man. I’m an international journalist, I explained, and the only people who’ll talk to me are pro-communists.

Next day he arranged for me to interview Rey Prendes, the culture and communications minister, Duarte’s closest cabinet colleague. Prendes was smart, charming, articulate, earthy.

I had a flowing beard and in Salvador’s heat and dust wore old jeans and an open neck shirt.

A driver I hired took to telling people, as a joke, I was a Maryknoll priest from the US.

Yikes! The death squads hated lefty priests.

I quickly developed my Spanish mantra – “Periodista (journalist) Australiano, non Americano. Kangaroo! Kangaroo!”

Security was ramshackle. A concrete wall outside my favourite cafe was there because guerillas had driven past and shot the place up.

A recent earthquake left gaping cracks in my hotel’s walls. I was on the fifth floor and the power was out several hours a day.

All through the night I’d hear staccato bursts of gunfire.

Journalists went to the war in yellow taxis. I took one to Tejutepeque, about 70km east, to observe “civic action” by the army, that is, the army being nice. Like seemingly all foreigners, I was suffering epic Montezuma’s revenge.

On the way back, on an isolated country road, the cab broke down. The driver disappeared to find a fan belt.

Was the breakdown real? Here’s where I get kidnapped, or worse. I sat there, miserable as sin, for 30 minutes.

The driver returned with a fan belt; we drove home.

I badly wanted to interview D’Aubuisson, who was runner-up in the presidential election. Juana worked out a way. The National Assembly met in an open-air space under its earthquake-damaged building. Juana got us on to the premises. Like many men of his type, D’Aubuisson would always stop for a pretty woman.

Juana told me to wait in the shadows. As D’Aubuisson walked out, she asked if she could speak with him.

He stopped, and she then called me over and introduced her ugly Australian colleague.

American journalists had warned me D’Aubuisson went crazy if journalists mentioned death squads. So I planned to interview him for 10 minutes about politics, then raise the death squads and see what happened.

All through, his eyes burned. Lean and taut, there was something metallic about his manner, cold, furious, barely contained, a spring about to explode. His eyes bore in on me the whole time and he never stopped caressing the damn pistol.

He could read me. Just as I started asking about the death squads he said that’s enough, and stormed off. I was disappointed not to ask the big question, relieved to get through the interview, grateful to Juana, happy to have got him at all.

Nicaragua, a couple of months later, was nowhere near as much fun.

As it happened: El Salvador, 1987

A charming, dominating brute

I caught up with Major d’Aubuisson just after a session of the National Assembly had finished.

The other Arena (party) assembly members were standing in a circle around him and listening quietly as he appeared to be laying down the law to them, wagging his finger and talking furiously.

Major d’Aubuisson rarely talks to the press these days. He particularly hates the American press.

He agreed to talk to me outside the National Assembly building where he stood with a small coterie of admirers, cradling the fur-covered pistol pouch he carries with him everywhere.

He told me he had won the presidential election he had fought against Mr (Jose) Duarte in 1984 but that the CIA had rigged the election results for the Christian Democrats ...

There is no doubt that Major d’Aubuisson is a charming and dominating brute.

His eyes seem to be permanently on fire and talking to him you can sense his barely restrained energy, the impatience he is always struggling to control.

60th Anniversary Witnesses to history

For a journalist, no story comes close to this one

The Australian’s former US correspondent was outside the Capitol on the day an angry mob invaded, urged on by Donald Trump.

Simple instructions: ‘Wear a ballistic helmet and a bulletproof vest’

The kibbutzim might have been tiny villages but they were the model, in miniature, for how a future Israel could have looked next to its Palestinian neighbours. By all rights, our reporter shouldn’t have made it there. But he did.

A large Indigenous man on my porch had an unexpected message

The story of a marriage forbidden revealed systemic racism and led to a life-long connection. For our 60th birthday, Hugh Lunn recalls this touching story.

Inside story: How Osama bin Laden hid in plain sight

The Australian’s then-South Asian correspondent had numerous run-ins with armed Pakistani police while covering the story of the decade. But nothing they could dish out could have been worse than having to tell the editor she’d been kicked out.

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

‘Stop the presses’: breaking the news of new pope

When the wisps of white smoke billowed from the Vatican chimney, The Australian newspaper had long been put to bed. Our correspondent couldn’t wait another day to file. We share this story for our 60th anniversary.

The first big yarn to take a toll on Hedley Thomas

Being sent to cover the bloody overthrow of the communist regime in Romania was a seminal experience for a young reporter who would become one of The Australian’s most highly acclaimed journalists.

At the scene of the story that gripped the world

Reporting from the muddy mouth of the cave complex as a monsoon loomed, it felt crushingly inevitable we would be relaying grim news about a trapped junior soccer team. But then came a sudden turn.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout